"When You’re Diagnosed with Autism—by TikTok" by Lucy Kross Wallace

When You’re Diagnosed with Autism—by TikTok

Do you ever seek reassurance, overspend, get angry over small things, fear abandonment, or pretend to be happy? If so, you might be suffering from anxiety, self-harm, ADHD, a wounded inner child, and something called “smiling depression”—at least according to the gurus of the video-sharing site TikTok, where the hashtag #selfdiagnosis has accrued over 13.5 million views. In many of the most widely surfed parts of the online world, it turns out, having a psychiatric condition isn’t just acceptable; it’s quirky, trendy, even desirable. It offers a victim-based identity, an excuse for one’s shortcomings, and a source of moral authority.

I’m not talking about reputable social-media accounts, including those run by doctors and therapists, which shed light on stigmatized conditions and aim to educate the public. Some mental illnesses are indeed significantly underdiagnosed, and social media offers one way to spread legitimate information about symptoms and treatment options. The problem isn’t that individuals are finding new digital avenues to understand their suspected cognitive, emotional, and behavioral disorders. It’s that these avenues now commonly distort the definition of “disorder” to the point of meaninglessness.

Being normal used to be normal. Everyday forgetfulness was solved with post-its, not pills. Awkward didn’t equal autistic. Of course, people got nervous before tests and miserable after breakups. Sadness and fear were symptoms … of being human. So how did mental illness go from a taboo topic to a TikTok growth field?

Psychiatrist Allen Frances, chair of the 1994 DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, warned of this trend in 2012, when he critiqued its successor, DSM-5. Since the publication of the first DSM in 1952 by the American Psychiatric Association, these texts have presented mental-health professionals with a standardized, APA-approved classification system for mental disorders. Writing in Psychology Today almost a decade ago, Frances warned that:

DSM 5 will turn temper tantrums into a mental disorder—a puzzling decision based on the work of only one research group. We have no idea whatever how this untested new diagnosis will play out in real-life practice settings, but my fear is that it will exacerbate, not relieve, the already excessive and inappropriate use of medication in young children. During the past two decades, child psychiatry has already provoked three fads—a tripling of Attention Deficit Disorder, a more than 20-times increase in Autistic Disorder, and a 40-times increase in childhood Bipolar Disorder. The field should have felt chastened by this sorry track record and should engage itself now in the crucial task of educating practitioners and the public about the difficulty of accurately diagnosing children and the risks of over-medicating them. DSM 5 should not be adding a new disorder likely to result in a new fad and even more inappropriate medication use in vulnerable children.

In his 2013 book, Saving

Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-Of-Control Psychiatric

Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life, Frances

identified two broad types of diagnostic changes that he found

especially concerning. First, small revisions lowered the threshold for

diagnosing a variety of conditions, including major depression, ADHD,

and anxiety. Under the newly expanded definitions, Frances argued, the

concept of mental illness could swell to encompass everything from grief

to immaturity. Second, commonly exhibited behaviors such as

forgetfulness, overeating, chronic pain, and temper tantrums were linked

to psychiatric issues, thanks to the inclusion of over a dozen new disorders.

In his 2013 book, Saving

Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-Of-Control Psychiatric

Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life, Frances

identified two broad types of diagnostic changes that he found

especially concerning. First, small revisions lowered the threshold for

diagnosing a variety of conditions, including major depression, ADHD,

and anxiety. Under the newly expanded definitions, Frances argued, the

concept of mental illness could swell to encompass everything from grief

to immaturity. Second, commonly exhibited behaviors such as

forgetfulness, overeating, chronic pain, and temper tantrums were linked

to psychiatric issues, thanks to the inclusion of over a dozen new disorders.

Frances didn’t object to every DSM-5 change: Plenty of uncontroversial updates reflected widespread scientific consensus. But he maintained that the net effect would be overwhelmingly negative, blurring the line between illness and health. And while TikTok wasn’t yet around when Frances offered these warnings, its effects are consistent with his predictions.

Sample some of TikTok’s top #selfdiagnosis videos, and you’ll see

that the diagnoses are more about entertainment than education. Think

you might be neurodivergent? Try watching a video sideways to make sure. How about a minute-long autism screening or a 14-second test for arachnophobia? Or you could go the traditional route with videos about “most overlooked anxiety symptoms” (excessive burping; playing with hair; numbness), “hidden signs of depression” (slouching, smiling excessively), and “Seven signs you may have ADHD” (procrastination, talkativeness). One video instructs you to put a finger down for every item that describes you. Two fists equal a diagnosis.

Most TikTokers are too young to know it, but these clips echo a formula popularized over 20 years ago in what is believed to be the first-ever viral self-diagnosis video. In 1998, just before pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly’s patent on Prozac was set to expire, the company’s brain trust carved out a new market for the drug: those afflicted with the newly diagnosed condition of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. PMDD was said to be characterized by affective changes before menstruation (such as “mood swings, feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection, [and] marked irritability or anger or increased interpersonal conflicts”). Fortunately, it could be treated by a new Eli Lilly medication called “Sarafem”—pink and lavender pills that were chemically identical to the (green and yellow) Prozac. To promote Sarafem, Eli Lilly produced a pair of 30-second videos, with one featuring an irate-looking woman wrestling with an uncooperative shopping cart, and another starring a “bloated” woman accusing her husband of misplacing her car keys.

IMS Health, a (now defunct) company that tracked physician prescribing data, estimated that doctors wrote more than 200,000 prescriptions for Sarafem between its rollout and the end of 2000. Once patients were convinced that the PMDD diagnosis fit their condition, doctors noted, these women were less open to other explanations for distress—a testament to the power of Eli Lilly’s advertising campaign. To this day, PMDD has its own coded entry in DSM-5.

But when it comes to new, similarly dubious diagnoses on social media, large pharmaceutical companies don’t have to create TV ads or launch expensive marketing campaigns. Individual TikTokers are crowdsourcing the movement on their own initiative.

Zachery Dereniowski, a 20-something Canadian motivational speaker and medical student, appears on TikTok as @mdmotivator, an account with more than two million followers. He’s racked up almost 65 million likes with videos such as Signs You Did NOT Know You Have ‘High-Functioning’ Anxiety (“YOU HAVE VERY HIGH expectations of YOURSELF”) and Things You May NOT Know Are Symptoms of Depression (“you believe STRONGLY in ‘counting your blessings’ as the foundation of well-being”). These clips are sponsored by an online therapy platform that connects users to therapists via text and video chat.

TikTok’s worried well are the perfect market for these services, as the vast majority of the app’s self-diagnosis videos appear to provide little possibility of disconfirmation. And if you like one clip, dozens more will pop up on your feed to hammer home your newly embraced form of self-identification. In the online world, these follow-up videos are what pass for “second opinions.” Everyone seems to be in agreement—so how could the original diagnosis possibly have been wrong?

“Neurotypical people don’t wonder if they’re autistic,” one bespectacled brunette asserts. “If you’re questioning if you’re autistic, you probably are.”

Another user explains that “If you think that you’re not autistic because no one in your family is autistic, that doesn’t mean that you’re not autistic. It just means that half the people in your family are undiagnosed autistic.” After all, “the medical community has pretty much agreed at this point that autism runs in families.” The solution? “Be confident in your self-diagnosis. And then do what I did and go diagnose half your family!”

On TikTok, diagnostic labels don’t just designate conditions: They encompass a lifestyle, community, and culture. This helps explain why TikTokers react so indignantly when their diagnoses are questioned. It isn’t just their condition that’s put into question, but an entire newly created social ecosystem.

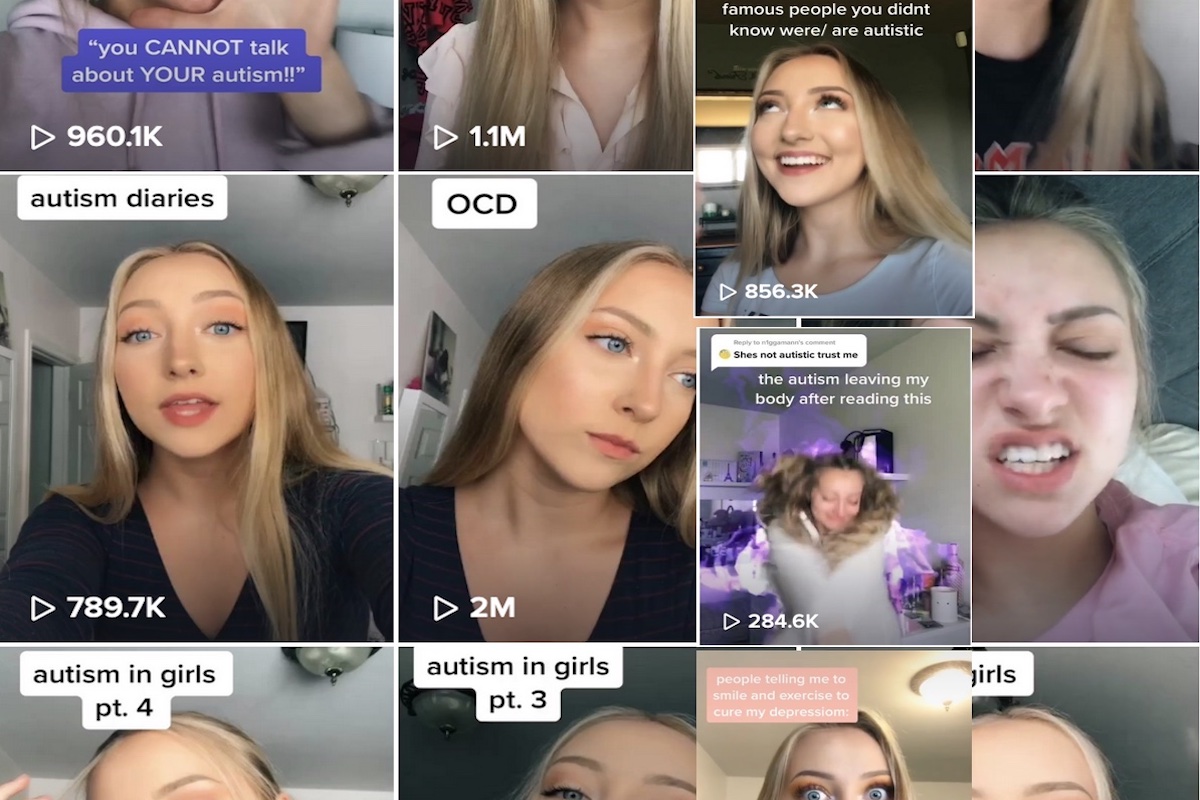

Paige Layle, a 20-year-old Canadian “autism influencer” (yes, that’s a thing) has been producing TikTok videos for just a year and a half, yet already has amassed 2.5 million followers. At first glance, she looks a bit like your average makeup-and-haul YouTuber—long blond hair, wide blue eyes, immaculate eyeshadow. But her channel focuses almost exclusively on disability. She’s uploaded hundreds of videos with messages like “welcome to autism tiktok,” in which she lip-syncs, flaps her hands, chews a rubber necklace, and sways dreamily to rap music. “Come for the vibes, stay for the knowledge!” the captions floating above her head read. “You can learn new things and help rid the world of ableism.”

Although Layle doesn’t quite glorify autism (she posts extensively about the associated impairments), she also rebukes those who discuss treating or (theoretically) curing the condition, and sometimes seems as if she’s speaking on behalf of the entire “autistic community.” This latter term is more than a little misleading, as not everyone with autism shares the same opinions. Moreover, those severely affected by autism (or autism spectrum disorder, as it’s now more formally known) are sometimes unable to make their views known at all. Indeed, a lot of autism “influencers” tend not to talk about the fact that many on the spectrum will never have a chance to achieve fame or success precisely because of their autism.

In these TikTok subcultures, disability is currency. You’ll find endless reminders that “autism is a superpower,” and that we need more #affirmations for #adhdtiktok and #neurodiversity. You can watch stimming duets and slam poems, and surf a rich subgenre that might be described as autistic–girl–listens–to–song–with–headphones. You’ll learn that all your favorite fictional characters are on the spectrum. You’ll master the art of in-group behavior, and get advice on comebacks to fend off neurotypicals, especially those nasty “incel autistic ppl.”

Maybe you’re not autistic now. But hang around long enough and you may well change your mind. Or perhaps you’ll find out you have undiagnosed dyscalculia, hyperlexia, or any one of the dozens of other conditions that fall under the neurodivergence umbrella. The point is, you’re different. You’re special.

This is why doctors and other medical professionals are often described with suspicion in these forums: When a condition has become your source of moral authority, what incentive is there to get better?

“I cannot be the only one who’s afraid to get an official diagnosis,” begins a user named radicalrakeem in one TikTok clip, “because what if I walk in there and they tell me that, like, I’m completely neurotypical? Like, what am I supposed to do? It’s genuinely a fear of mine, because that means that all of this [waves at self] is a choice … Because that means I’m being annoying on purpose … like I could just change this any time I wanted to and I haven’t?” It’s a startling video to watch because radicalrakeem says the quiet part out loud: Users cling to labels because, without them, they won’t know how to acknowledge and address their shortcomings. And so the easiest way to avoid judgment—both from others and from oneself—is to claim a diagnosis.

It’s notable that no-one on TikTok is diagnosing themselves with schizophrenia or severe personality disorders such as antisocial and borderline. It’s hard to find videos about “high-functioning psychosis” or three clues that you might have a neurodegenerative illness, or five reasons to see bipolar as a blessing. Under the guise of activism and public awareness, self-diagnostic TikTokers have done a good job medicalizing their own quirks and flaws, while doing nothing for those afflicted with tragically debilitating psychiatric conditions that are the furthest thing from “superpowers.”

So enough about neurodiversity. Let’s bring back “nervous,” “sad,” “scared,” and every other banal emotion that belongs to everyone and, therefore, no one. We don’t need more variations on special. Instead, we ought to understand wellness as thoroughly as we do illness, developing a vocabulary that stops conflating malaise with disease. “Nine normal signs you’re nervous” and “seven symptoms of sadness” might not go viral, but they’d at least offer genuine insight into who most of us truly are.

Lucy Kross Wallace is an undergraduate at Stanford University. She is the author of the Quillette article My Brief Spell as an Activist, published in October 2020.

Source: Quillette

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Post-Partisan Emporium's Purpose and Standards

This site does not have a particular political position. We welcome articles from various points of view, and civil debate when differences arise.

Contributions of articles from posters are always welcome. Unless a contribution is really beyond the pale, we do not edit what goes up as topics for discussion. If you would like to contribute an article, let one of the moderators know. Likewise if you would like to become an official contributor so you can put up articles yourself, but for that we need to exchange email addresses and we need a Google email address from you.

Contributions can be anything, including fiction, poems, cartoons, or songs. They can be your own writing or someone else’s writing which has yet to be published.

We understand that tempers flare during heated conversations, and we're willing to overlook the occasional name-calling in that situation, although we do not encourage it. We also understand that some people enjoy pushing buttons and that cussing them out may be an understandable response, although we do not encourage that either. What we will not tolerate is a pattern of harassment and/or lies about other posters.

Comments

Post a Comment