Harvesting Discontent: The Global Farmer’s Revolt

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Harvesting Discontent: The Global Farmer’s Revolt

An agricultural revolution, farmers uprising worldwide, seeking to seed change…

Kristian James

21st Century Wire

When the ancestors of modern humans began to observe the cycles of plants, understanding the rhythm of the environment, and started utilizing the seed to plant the next crop. This knowledge solidified the formation of the beginning of agriculture. The end of roaming and hunting for food, the decision to gather together, and to prepare and wait for the success of good crops. Thus, farming developed as a skill integral to the development of all worldwide societies, defined by thousands of years of learned cultivation under the belts of countless generations, the ability to feed yourself and grow abundance, and also the ability to sell and trade. This is the very basis and crux of the world economy.

As we enter 2024, the year of the Dragon, Earth’s population has surpassed 8 billion, and the vital role of farming in sustaining the global populace should be of paramount importance. However, the nature of resource distribution across regions remains uneven, posing challenges to the self-sufficiency of nations. Amidst this backdrop, Europe is an agricultural haven with its rich, fertile soils, relatively stable geology, and temperate climates. Such favourable conditions provide European farmers with the unique opportunity to cultivate a diverse array of grains, fruits, and vegetables. Moreover, Europe’s present commitment to a top-down initiative to install sustainable green policy farming practices throughout the Union, albeit with elements that are at odds with one another. For instance, conservation initiatives and eco-friendly approaches on the one hand with the expectation of more goods and economic value on the other.

Because of this, European countries find themselves perhaps intentionally battling between bureaucracy, legislation and national food sovereignty, leading many farmers to reach a crescendo in a public display of slow-moving rallies and muck spreading on the doors of government offices. In the best interests of all, it is crucial that when farmers speak, we all lend our ears and pay attention.

The Farmers’ Protests happening across many European countries have broad similarities. One should be cautious about painting each country’s challenges with a single brush stroke. All of these share the fact that their direct actions and media visibility are all driving the inspiration globally for others to do the same. Many protests are different groups and alliances not necessarily walking the same path of experiences, yet the visual impact is louder together and has been very successful so far in highlighting the inequities and injustices they feel that they are facing collectively.

The Farmers’ Protests happening across many European countries have broad similarities. One should be cautious about painting each country’s challenges with a single brush stroke. All of these share the fact that their direct actions and media visibility are all driving the inspiration globally for others to do the same. Many protests are different groups and alliances not necessarily walking the same path of experiences, yet the visual impact is louder together and has been very successful so far in highlighting the inequities and injustices they feel that they are facing collectively.

Since October 2019, Dutch farmers have been furiously protesting against emission reduction targets and contentious environmental policies. In order to align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG) and the WEF ‘Great Reset’ consensus, and to address the environmental damage caused by industrialized Big Agra farming, the Dutch ruling coalition is committed to cutting both CO2 emissions and pollutants, predominantly nitrogen oxide and ammonia, by 50% nationwide by 2030.

An advisory committee, led by former Deputy Prime Minister Johan Remkes, declared that their government must take ‘drastic measures’ to reduce national nitrogen emissions. According to the committee’s report, the proposed measures include buying out and closing down livestock farms. The Dutch government commissioned a report published in June 2020, titled ‘Not everything is possible,’ resulting in compounding frustration as even tighter environmental targets were set with deep expectations for the coming years.

Small to medium-sized farms now find themselves reclassified as large farms due to a recent change by the Dutch government in the threshold number of livestock for this designation. As a result, agricultural farmers now face increased charges and may need to slaughter large numbers of their healthy livestock to comply with legislation surrounding Net Zero and Carbon Neutrality policies. In July 2022, in the Netherlands, police opened fire on protesting farmers in Friesland following a sequence of events stemming from newly signed in Agra policies requiring them to reduce their volume of rural livestock by as much as 70%. The news soon shifted from page 7 in a sidebar to being the focus of attention on the front page, the spark was lit.

Similar legislation has landed at the feet of farmers in Ireland, where the Environmental Protection Agency claims that the agricultural sector accounted for 38 per cent of national greenhouse gas emissions in 2021. As they aim to reduce all agricultural emissions by 25 per cent by 2030, this directive effectively means the cows have to go. It is estimated that 200,000 healthy cattle under such draconian legislation will be sent to slaughterhouses.

In March 2023, 2,700 farmers with a wagon train of tractors descended into the streets of Brussels. Regional agricultural organizations, in a joint statement, expressed concerns that the existing nitrogen agreement ‘will cause socio-economic carnage.’ They urged for a revised agreement that better aligns with the future prospects of the farming sector.

September 2023 saw more than a thousand Swedish farmers and supporters rally to convince politicians to launch a series of measures designed to rescue milk production in Sweden, including financial support for farmers and raised diesel tax refunds for agriculture companies.

The French are renowned for their passionate approaches to protesting. In a creative twist, farmers have taken to the country’s motorways and byways, initiating the movement called ‘On marche sur la tête.’ This movement has garnered support with thousands of signatures, and its participants convey their message by creatively flipping town and road signs upside down. This action sends a clear statement to every passing motorist, emphasizing that collectively, ‘we are walking on our heads!’ Another layer of contention is simultaneously being raised— the deliberate lack of investment in the sector. Agricultural workers initiated their recent protest on January 16th, with over a thousand farmers forming slow-moving convoys and demonstrating in central Toulouse. The A64 South of Toulouse remains gridlocked in both directions. Since the beginning, the movement has grown substantially as five additional protests have blocked connecting motorway junctions, with the potential for sporadic new ones branching out and entrenching their positions.

The French are renowned for their passionate approaches to protesting. In a creative twist, farmers have taken to the country’s motorways and byways, initiating the movement called ‘On marche sur la tête.’ This movement has garnered support with thousands of signatures, and its participants convey their message by creatively flipping town and road signs upside down. This action sends a clear statement to every passing motorist, emphasizing that collectively, ‘we are walking on our heads!’ Another layer of contention is simultaneously being raised— the deliberate lack of investment in the sector. Agricultural workers initiated their recent protest on January 16th, with over a thousand farmers forming slow-moving convoys and demonstrating in central Toulouse. The A64 South of Toulouse remains gridlocked in both directions. Since the beginning, the movement has grown substantially as five additional protests have blocked connecting motorway junctions, with the potential for sporadic new ones branching out and entrenching their positions.

Across the border in Germany, Olaf Scholz with the Social Democratic Party decided to cut internal costs by eliminating the tax exemption on vehicles and diesel fuel for non-road use. This, in turn, has aggravated farmers and the rural community who are already grappling with higher-than-average inflation and a cost-of-living crisis. As a result, the operating costs and prices of tractors and farming equipment have skyrocketed.

In a time of extremely tight profit margins and facing competition from cheaper imports, particularly from Ukraine as part of the ongoing EU trade deals with Zelensky. German farmers claim they cannot cope with their businesses and livelihoods facing bankruptcy. Following the Ukraine war, there was a notable 45% surge in profits attributed to an 80% spike in wheat prices. Although the market price has since reverted to pre-war levels, production costs have risen due to elevated gas and diesel prices. It is extremely difficult to reconcile a government telling their farmers they should pay their share when they are producing food at nearly the cost of production. And, by the way, we want to increase your cost of production. Facing an uncertain future in German agriculture, farmers believe their only recourse is to join hands with their counterparts in France and the Netherlands. United in solidarity, they have taken to the streets, raising their voices to make their valid concerns known.

Arnaud Rousseau, the director of the French Farming Union FNSEA, voices his concerns, highlighting that ‘55% of the chicken consumed in France is now imported,’ raising worries about French poultry production. This presents a dual challenge as the nation continues to recover from the 2022 avian flu crisis, marked by the significant poultry culling, and the additional hurdle from the duty-free imports agreement supporting the EU’s arrangement with Ukraine. Farmers are grappling with the difficulty of competing against inexpensive and lower-quality imports.

Across Poland, Slovakia and Romania, protests have arisen due to the increased presence of cheaper Ukrainian products in the markets. Still reeling and recovering from agriculture-destroying disasters with droughts, floods and forest fires affecting their volume output in recent times farmers feel they are being treated unfairly. Moldovian and Hungarian truckers and farmers initiated strong blockades at the border with Ukraine. The respective countries’ farmers are expressing frustration that Ukrainian truck drivers can enter the EU without permits. Selling agricultural products at prices so undercut that local competition becomes untenable. This situation is aggravated by increased operating costs, heightened diesel and insurance rates, and the EU’s imposition of Net Zero-driven environmental protection regulations. The difficult matter of financial subsidies has come to the forefront, and as of January 22nd, seems to be tentatively resolved. This development follows an agreement between farmers’ associations and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, in which the government has committed to subsidizing all agricultural excise taxes until 2026.

Other grievances

Lithuanian farmers are protesting, reflecting shared challenges with their European counterparts and an additional geopolitical perspective.

On January 23rd, a thousand-strong tractor convoy, organized by the Council of Agriculture (ZUT), rode into the capital of Vilnius, causing disruption, including deliberately mucking the Government of Lithuania parliamentary building. A near-continuous cacophony of horns has followed staging a vehicle sit-in that was set to last until the 26th, with the possibility of an extension. Their demonstration aims to address concerns about increased fuel excise taxes and the transportation of Russian grain through Lithuania. They walk and drive together, united by different reasons. Italy’s central government also faces discontent with its support of EU environmental policies, resulting in many major cities—Rome, Bologna, Florence, Milan, and Naples—experiencing a rolling slow procession of tractors. Road users are being advised not to travel.

Videos on social media are gaining phenomenal traction and shares, with Finland’s rural community beginning to join this week to show support for their fellow Europeans, channelling their concerns about subsidies and the cost of operations. In the Scottish Highlands, farmers’ frustrations echo as crofters and farmer groups drive a procession through Grantown to the offices of the Cairngorm National Park Authority, expressing their dissatisfaction with the lack of consultations regarding the reintroduction of beavers to the region. Within the gathering, signs voice various objections, primarily centred around the reduction of farmland. Contesting the rewilding initiatives.

Videos on social media are gaining phenomenal traction and shares, with Finland’s rural community beginning to join this week to show support for their fellow Europeans, channelling their concerns about subsidies and the cost of operations. In the Scottish Highlands, farmers’ frustrations echo as crofters and farmer groups drive a procession through Grantown to the offices of the Cairngorm National Park Authority, expressing their dissatisfaction with the lack of consultations regarding the reintroduction of beavers to the region. Within the gathering, signs voice various objections, primarily centred around the reduction of farmland. Contesting the rewilding initiatives.

London is not immune to farmers’ protests, as 49 scarecrows stood placed outside Britain’s parliament on Monday 22nd January as UK fruit and vegetable farmers protested against “unfair” treatment by the country’s six largest supermarket chains. Calling for greater legal protections and support. The number of scarecrows is representative of the 49% of British farmers who are on the brink of collapse or walking away from the industry. Due to supermarkets minimizing pricing practices to be competitive, rejecting stock and simply not paying fairly. The government has pledged to support their position. The optics are in line with the timing to be included with the “Farmers Revolt”.

Public support for the importance of the farming industry has swelled beyond the borders of Europe. Bolivia finds itself facing difficult times, as activists and protestors staged nationwide disruption on the 22nd of January. The activists are supporters of former president Evo Morales who was ousted in an apparent coup and are affiliated with the Single Union Confederation of Peasant Workers of Bolivia (Confederacion Sindical Unica de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia, CSUTCB). Evo Morales was a former crop farmer who rose to prominence and became president in 2007. Police and demonstrators have clashed. More than half of Bolivia’s population lives in rural areas where poverty rates are the highest. 75% of Bolivian families don’t have regular access to food. Rural households heavily depend on small-scale farming to survive. Any disruption threatens the lives and livelihood of the Bolivian people. South American countries which import much of their fertilizers. Farmers have seen the cost of a single bag of fertilizer increase from one productive season to another since September 2021. The cost of fertilizers has increased so dramatically across Central American countries that resource-constrained farmers have to decide to reduce the volume of fertilizer amount they use, plant less, and increase prices of the crops they sell. These responses threaten further increases in food insecurity in a region where food inflation is escalating.

Understanding the co-dependence of energy, fertilizer, and food prices

Due to the significant role of natural gas in the production of Nitrogen-based fertilizers (constituting approximately 80 per cent of production costs for urea), global fertilizer prices are closely tied to global natural gas prices. What are considered to be fossil fuels underpins the production of synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. Natural gas is burned to extract liquid ammonia. This potent substance is high in nitrogen content so acts as an effective fertiliser. However, burning natural gas produces greenhouse gases including methane and carbon dioxide as waste products released into the atmosphere – considered to contribute to a shifting of the climate. Since late 2020, global fertilizer prices have been on the rise, the induced disruptions to logistics chains by the virus of unknown origin Covid-19, and high energy prices. At the end of September 2021, as early signs of a pandemic recovery led to higher fuel and natural gas prices, urea and DAP prices jumped respectively to 300% and 200% of their value in September 2020. In 2022, the Russia-Ukraine crisis triggered a more aggressive hike in energy and fertilizer prices, because of the inability of Belarus and Russia to export to certain markets.

The global interconnected fertilizer market is experiencing great turbulence, with every action causing a difficult ripple to traverse, its effects having real-life and death consequences.

Discontent and revolt

“What brings us closer together is the questioning of this European vision, not the Green Deal, which raises questions about the necessary transition, but the ‘de-growth’ part of the vision of production,” stressed Rousseau, who says he is in regular contact with his German counterparts from the main German farmers’ union and organiser of the protests, the DBV. Widening knowledge that there is a systemic practice that has engaged to downscale, downgrade agriculture and ultimately put a hardline limit on the availability to produce fresh food. What we have is a contagion, a revolt of the people, a collective revolt of the workers emboldened by the worldwide visibility of the struggles they are enduring. Amplified by social media. They realize the rural challenges they have are not just localized, they are shared with others beyond their borders. The tightening visions by those whose plans are for globalization. Whilst there is potential for governments to be forced to continue subsidies to quell the crowds. Realistically this can only be a short-term solution. The kicking of the proverbial can down the road before the crisis looms again.

Image Credit: Kees Torn (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Food security

A prominent theme emerges around food security, where the potential exists to make it financially challenging for family farms to sustain operations, compelling them to sell up. Subsequently, corporations could acquire the land and further industrialize farming, or allow the land to go idle, aligning with rewilding legislation that underpins and, in turn, limits the available food supply. The ultimate goal appears to be a shift in land ownership from the people to corporations. This involves scaling back volume production, limiting surplus, and strategically navigating the pressures of commodities, making them more valuable through their scarcity. In this scenario, someone stands to gain more for less. The farmers, grounded in their daily work, understand the pivotal role they play in the delicate chain of food availability. Through their public actions, they emphasize key points, highlighting the critical importance of ensuring food success and the consequences if it doesn’t happen.

Food security and environmental damage control, are also tied together with the overuse of nitrogen and ammonia used to boost food growth to meet the demand. Excess nitrogen leaking into the environment has a notable impact on the ecosystem. Most plants cannot tolerate synthetic fertilisers or high levels of nitrogen. Nitrogen pollution causes nitrogen-tolerant species to thrive and outcompete more sensitive wild plants and fungi. This reduces wildlife diversity and damages plant health. Continued reliance on nitrogen fertilizers is tipping the balance, towards another catastrophe, acidification of soil. Once the soil is damaged, its chances of recovering essential minerals and regaining viability diminish significantly, leading to a progressive decline in productivity. This relentless deterioration cycle will ultimately culminate in lifeless soil. The environmental policies that are considered detrimental to the present-day farmer in the future there may be a time when people look back and say not enough was done to protect the valuable soils.

Food security and environmental damage control, are also tied together with the overuse of nitrogen and ammonia used to boost food growth to meet the demand. Excess nitrogen leaking into the environment has a notable impact on the ecosystem. Most plants cannot tolerate synthetic fertilisers or high levels of nitrogen. Nitrogen pollution causes nitrogen-tolerant species to thrive and outcompete more sensitive wild plants and fungi. This reduces wildlife diversity and damages plant health. Continued reliance on nitrogen fertilizers is tipping the balance, towards another catastrophe, acidification of soil. Once the soil is damaged, its chances of recovering essential minerals and regaining viability diminish significantly, leading to a progressive decline in productivity. This relentless deterioration cycle will ultimately culminate in lifeless soil. The environmental policies that are considered detrimental to the present-day farmer in the future there may be a time when people look back and say not enough was done to protect the valuable soils.

Globalization is elevating the levels of interdependence among states that are becoming more deeply integrated into a homogenous economy. This is that period where there is a hammering out of how it works in practice. Seeing where the chips fall as the analogy goes. Seems that nation-states will be progressively pressured by the range and complexity of multiple issues, where only a wider planned solution of integration is seen as the only viable option.

Spectacle of defiance

Tractors press their horns in the thousands around the globe, and yellow flashing beacons light up the streets in unison, a spectacle of defiance. Unspoken of is the silent majority, unable to attend the protests because of the value of their work that needs to be done. Cows need milking, crops need attending, and relentless expectation because their margins don’t allow for downtime. The supermarkets have contracts expecting to be filled and suppliers demanding goods signed months ago. It’s a needs-must situation for likely most of the active farmers.

Considering the similarity to the Truckers Convoy in Canada, regular people, other truckers, and anyone who showed support and solidarity for their plight, or even liked a tweet. Had bank accounts frozen, faced arrest, and surveillance and was labelled as far-right. The farmers’ protests are being characterized by the legacy media as leaning toward the far-right perspective. Food and clean water security are beginning to dominate the conversation, even in mainstream discussions. The looming possibility of a significant pricing shock, potentially stemming from energy challenges or crop failures, carries the potential to set off a chain reaction akin to dominos cascading through crucial international markets across various sectors. Complex interdependence and transnational networks for the supply of basic human needs, such as food and water no longer able to be provided by the country internally. The domino falling could lead to severe infrastructure failures, a likely collapse of public services and driving society into desperate conflict. What then of stability, security and political order? One should pose the viable questions: Is this orchestrated? What purpose does a U.N.-mandated 30% reduction in food production, coupled with embedded Net Zero goals, serve?

Food and clean water security are beginning to dominate the conversation, even in mainstream discussions. The looming possibility of a significant pricing shock, potentially stemming from energy challenges or crop failures, carries the potential to set off a chain reaction akin to dominos cascading through crucial international markets across various sectors. Complex interdependence and transnational networks for the supply of basic human needs, such as food and water no longer able to be provided by the country internally. The domino falling could lead to severe infrastructure failures, a likely collapse of public services and driving society into desperate conflict. What then of stability, security and political order? One should pose the viable questions: Is this orchestrated? What purpose does a U.N.-mandated 30% reduction in food production, coupled with embedded Net Zero goals, serve?

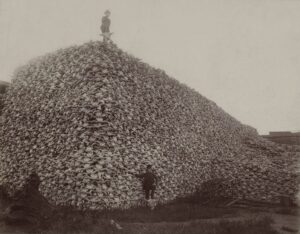

An event from history in North America is notably worth drawing a crucial parallel to. The mass killing of buffalo herds was part of a deliberate strategy by the U.S. government and settlers to undermine the traditional way of life of Native American Plains tribes, who heavily relied on buffalo for sustenance, cultural practices, and material needs. This strategy aimed to force Native Americans onto reservations and open up the Great Plains. The mass slaughter of buffalo had devastating consequences for Native American communities, contributing to the loss of their traditional lifestyle and dependence on buffalo herds. It was not a direct act of subjugation but rather a tactic used to exert control over Native American lands and resources.

Could the deliberate reduction of farmland, food availability and coupled with the subsequent transfer of land and wealth be a deliberate effort to sow chaos or perhaps a strategy aimed at destabilizing nations? Exerting the control to reduce the population in line with the statements, comments and published works as they attune the world, towards The Great Reset.

Source: 21stCenturyWire

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment