"The Spectrum": How Autism Was Hijacked By Narcissists

"The Spectrum": How Autism Was Hijacked By Narcissists

The ideological capture and cultural rebranding of Autism

When Leo Kanner first defined autism in 1943, it was estimated that 4 to 5 children per 10,000 were affected. Today, the CDC puts that number at 1 in 36, almost one child in every classroom. If any other medical condition, blindness, epilepsy or paralysis showed a spike like this, it would trigger a pandemic-level outcry. But with autism, we see at best a curious murmuring as to what this is, and at worst, a growing chorus of people insisting, they too, belong in the group.

From experts, instead of raised alarms or calls for serious public health investigation (as would be expected for any other childhood disorder) we get calls for inclusivity and a self-congratulatory attitude toward their advancement in diagnostic understanding and tools. Another example of ideological capture of psychiatry by cultural sentiment.

Characters like Sheldon Cooper and Sherlock Holmes have helped turn the image of autism into a badge of honour. It means you’re socially odd, intellectually superior, and emotionally detached in an edgy and endearing way. For many, especially mothers with narcissistic tendencies hungry for a narrative of exceptionalism, this offered a seductive reframing of their child’s misbehaviour and non-conformity as evidence of giftedness. She could thus become the one who gave birth to the quirky but special genius. She alone saw the hidden brilliance beneath the “weird” behaviour. She became the martyr and the insider to an elite subculture. It’s Munchausen by proxy, 2025 edition.

People with narcissism and psychopathic traits exploit wherever they can, we know this. And yet again, psychiatry, the ones who should be the best at recognizing these, made it easy pickings by flinging the diagnostic gates wide open. Longtime readers will recognize the pattern: I’ve written before about the diagnostic creep in trauma, expanding definitions that blur the line between disorder and ordinary variation. The same diagnostic creep has unfolded here. Autism, once narrowly defined, was steadily loosened through each revision of the DSM.

The Great Diagnostic Expansion

Originally, Kanner’s autism was unmistakable: nonverbal children, socially disconnected, cognitively impaired, often with seizures. These were not quirky introverts. These were children who required full-time care and specialized schooling. In the DSM-III of the 1980s, it was called infantile autism. The criteria required clear onset before 30 months, marked language delays, gross deficits in social interaction, and repetitive behaviours. These were developmental dysfunctions, not misunderstood personalities. And neither clinicians nor parents had a problem naming them as such.

Then came the DSM-III-R in 1987, which introduced pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) and broadened the field significantly. Suddenly, language delay and intellectual disability were no longer central. Subclinical cases were included. Asperger’s Syndrome followed in the DSM-IV in 1994, adding high-IQ individuals with no language delays but poor social functioning. A child who spoke on time but didn’t understand jokes, had poor eye contact, and rigid routines was now also autistic.

But the most dramatic change came with DSM-5 in 2013. The subtypes were eliminated. Autism became one spectrum. The criteria were thinned down to two domains: social communication difficulties and restrictive, repetitive behaviours. A person needed to meet just six out of twelve traits, spread across these two clusters. Language and cognitive delay? Optional. Even the requirement for early onset was removed. A diagnosis could now be given based on historical symptoms. Questionnaires like the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) are so broad and subjective they can be easily gamed. This made it possible for 30-year-olds to recall feeling “socially overwhelmed” in school and not liking itchy clothing to receive the same diagnosis as a nonverbal child requiring lifelong care.

The diagnostic category has become a black hole, pulling in people with no clinical resemblance, collapsing distinction into sameness. From what I’ve observed, three distinct autism “patients” now account for much of the increased prevalence, none of whom would have qualified under the original criteria.

From Eccentric to “On the Spectrum”

The first is the temperamentally awkward, quiet child. Highly conscientious, literal-minded, with a strong preference for things rather than people. He can spend hours absorbed in intricate play, needing much coercion to focus attention elsewhere. In the subsequent forced social settings, he comes across as “weird.” Once considered an introverted, eccentric personality, all it takes is a mother looking for social cache through a child who embarrasses her.

The diagnostic confusion of the autism spectrum, coupled with the charming characters dominating TV shows, has influence parental behaviour in a culture where narcissism blooms unchecked and personality psychology is forgotten. This is evident on the countless parenting blogs chronicling their “autism journey.”

One striking example of how blurred diagnostic categories play out is in the interpretation of stimming, a key defining features of autism. It’s an involuntary, neurologically driven motor response to sensory overload: repetitive, unconscious, and difficult to suppress. The stimming these parents describe, however, is indistinguishable from what any typical two- or three-year-old does: hand-flapping, spinning, lining things up. Such behaviour can after all, to a certain degree, be found in all people. What’s presented as evidence of neurodivergence is often just a developmental phase, later reframed through the influence of online checklists and the retroactive placement of unreliable memories.

A common thread in these stories is the initial dismissal by general paediatricians trained to distinguish normal developmental variation. After enough doctor-shopping and vague questionnaires, the parent eventually finds someone willing to confirm what they’ve already decided: that the son’s aloofness is hidden brilliance. The diagnosis is finally secured by an ideological autism centre clinician, trained not to evaluate critically, but to recognize and affirm such “symptoms.”

From Brat to “Differently Wired”

The second is the undisciplined child. Verbally skilled, highly functional, but socially inept. Paediatricians often see nothing wrong, because there isn’t a developmental delay. But in the classroom, the behaviour becomes disruptive, teachers grow exhausted, parents give up. Between the second and fourth grade, the diagnosis is sought, not from a clinical need, but from institutional surrender.

The Narcissist in Neurodivergent Clothing

The third is the adult Cluster B case. On TikTok, they proudly recount their autism diagnosis as if they were Ivy-league diplomas. To the trained eye, what’s on display is emotional immaturity, narcissistic attention-seeking (“I am the best at being oppressed because I’m special”) and interpersonal manipulation. There’s a certain sadistic pleasure in making others uncomfortable by refusing to conform socially.

Their immaturity is obvious in the way they label the rest of society as “phony” and “fake,” casting themselves as the only ones authentic enough to speak the truth, regardless of its impact. It’s the same adolescent script performed since the dawn of time. Only now, the diagnosis confirms their righteousness: They’re told they’re wired differently, that their discomfort is insight, and their perspective a rare gift to be bestowed on society. And thus, maturation is stalled.

The performative tendencies of Cluster B patients have them mimicking classic autistic behaviours, like the aforementioned stimming. What these patients call stimming, is often a form of self-soothing taught in therapy, where repetitive motion and sensory grounding techniques are used to manage emotional dysregulation. But there’s a critical difference. In autism, it’s a symptom of underlying neurological dysfunction; the other is a practiced coping mechanism. They may look the same on the surface, but they emerge from entirely different clinical realities.

Any attempt to question these realities is swiftly met with the concept of masking. Masking now functions as a catch-all excuse: if you don't meet diagnostic criteria, it’s not because you're not autistic, it’s because you’ve been too good at hiding it. Your true self oppressed by an old-fashioned society. But the research on masking is methodologically flawed, relying heavily on interpretations of retrospective self-reports from adults diagnosed in their 30s, samples drawn from those already invested in the diagnosis.

It’s circular: if you say you were masking, that becomes proof enough that you were autistic all along. Most people would consider “masking” no different from the politeness I educate my three small children to show. An ability to put aside their immediate whims to function in a society one day. It’s not evidence of hidden pathology. It’s socialisation.

The Ideological Rebrand of Autism

This exploitation is made more appealing by the transformation of autism from dysfunction to “difference.” A deliberate move away from the medical model of disability, by the neurodiversity movement. In the 1990s, sociologist Judy Singer coined the term neurodiversity, framing autism as a natural variation of the human mind, no longer a developmental disorder; it was a “neurotype.” However, the term “neurodivergence” crumbles under the slightest scrutiny. There is no clinically defined “neurotypical,” brain, and no bimodal distribution that separates autistic from non-autistic minds.

Groups like the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) ran with the unscientific term and lobbied fiercely to widen the diagnosis, especially during the DSM-5 revisions. They demanded the inclusion of “historical” symptoms, enabling adult self-diagnosis. Their mission wasn’t diagnostic precision, but diagnostic access.

There are several such activist groups, each having played their role in leaving the real autists behind. Because they all insist autism is not an impairment to be treated, but a unique perspective to be honed. Some activists of the movement later going as far as calling it a “superpower.”

Under this framework, to describe someone as “low functioning” is offensive, and to seek behavioural modification recast as ableism by those lacking understanding. There is no hierarchy of function, but diverse minds, all equally valid. It follows that autists should be offered neurodiversity-affirming interventions and programs tailored to their strengths.

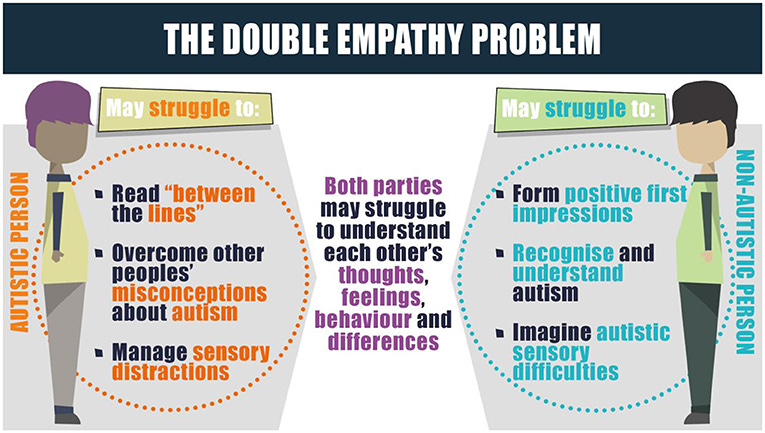

In this vein, another idea that’s gained traction under the neurodiversity banner is the “double empathy problem.” The theory claims that communication difficulties between autistic and non-autistic people aren’t due to a lack of empathy or social skill in the autistic individual, but to a mismatch in communication styles between the two groups. They claim autistic people understand each other just fine; it’s only when interacting with “neurotypicals” that problems arise. So, what was once viewed as a core deficit in social reciprocity is reinterpreted as mutual misunderstanding. Leave aside that the research in this is weak, the real problem is that it flips the burden of adaptation: “Why should I be the one to make myself understood when we are equally at fault?” Not exactly creating incentives to improve functioning in the real world. Which is the intended effect.

And this was perfectly illustrated in a recent conversation between Dr. Jordan B. Peterson and Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen, one of the key architects of the modern autism framework. Peterson pressed him to define what “severe autism” looks like. Baron-Cohen deflected, saying autism is a spectrum and “always looks different.” A pitch for dismantling hierarchy. As if gradations of function aren’t diagnostically relevant, instead, they demonstrate your lack of understanding on the subject. His answers revealed ideology overshadowing clinical clarity: vague empathy trumping the precise language we need to create categories that helps us identify correct treatment. The ones most affected by this euphemistic fog are not the high-functioning adults demanding validation, it’s the children who still cannot speak, and whose parents are begging to know: Will they ever be able to live independently?

This ideological shift away from functioning didn’t just change how we diagnose. It changed how we treat.

Outside of the Lab this has Real-World Consequences

In the classical model, when autism was widely accepted as a developmental disorder, treatment was structured, measurable, and goal oriented. It aimed at improving functionality: language acquisition, daily living skills, social adaptation. Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), for all its controversies, was built around this principle. It broke tasks down into manageable steps and used reinforcement to shape behaviour. ABA alongside speech therapy, occupational therapy, special education were targeted interventions where progress could be tracked. The goal wasn’t to eliminate autism: it was to reduce dysfunction and build independence. And we have collected solid evidence, it works.

Floor time, DIR, child-led therapy are approaches are marketed as humane alternatives to the supposedly oppressive structure of ABA. But they offer no measurable outcomes, no behavioural goals, and little evidence of progress. They rely on vague concepts like attunement and connection, and therapists are instructed to avoid correction and excessive coaxing. Children are encouraged to “unmask,” to stim freely, meltdowns and aggression viewed as communication. “Sensory rooms” are prioritized over skill-building and parents are coached into oblivion to be 24/7 facilitators of co-regulation, abandoning discipline altogether. It places enormous emotional burden on already overwhelmed families, while leaving the most impaired children to flounder, missing key developmental windows where behaviour can be learned.

The Hidden Casualties of Inclusivity

Autists themselves are not the only ones harmed by the consequences of the obsession with inclusivity. In schools, Children with severe behavioural challenges are now placed full-time in mainstream classrooms. Paraprofessionals with minimal training act as substitutes for specialized care. In the U.S., special‐education spending per student with disabilities ranged from $10,500 to $20,100, nearly double the cost for general‑education students, but since the inclusion mandate, funding has stagnated at around 15%. Roughly 7.5 million U.S. students receive special–ed services, about 15% of all public-school students. Where districts are lucky enough to have trained special-ed teachers, turnover is high, with burnout cited as a primary reason for leaving.

Aside from the exhausted staff, neurotypical classmates are forced to tolerate disrupted learning and even bodily harm. Every complaint after being spat on or kicked at met only with a bid for more understanding and empathy, as if it were some sort of penance for being born neurotypical (or raised with discipline).

For all the compassion claimed by progressive, out-of-touch psychologists, psychiatrists, social scientists, and activists driving this shift, convincing both autists and non-autists that society is to blame for expecting basic conformity isn’t kindness. It’s cruelty. It’s cruel to the truly autistic children who need structured care and specialized environments, not resentful stares from classmates. A mere preview of the adult world they’re not being prepared for. It’s cruel to the Cluster B patients who require a diagnosis directing them to Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), not a neurodivergent label that excuses every impulse DBT works to curb. It’s cruel to the awkward, odd child who simply needs to be left alone, not pathologized. And it’s cruel to the undisciplined child who needs boundaries firmly enforced, not a diagnosis that grants him access to a “sensory room” and even fewer expectations.

Source: Psychobabble

Comments

Post a Comment