Horse-Bleep: How 4 Calls on Animal Ivermectin Launched a False FDA-Media Attack on a Life-Saving Human Medicine

Horse-Bleep: How 4 Calls on Animal Ivermectin Launched a False FDA-Media Attack on a Life-Saving Human Medicine

Our investigative reporters dug up the FDA memos documenting the start of a propaganda campaign, and got The New York Times to correct its false reporting.

The Propaganda That Started The Big Lie:

In a hokey tweet on August 21, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration told Americans the obvious: “You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it.”

Everyone knew what “it” was: an animal form of the drug ivermectin that folks were said to be using, widely, for covid-19. Don’t, said FDA.

Within two days, 23.7 million people had seen that Pulitzer-worthy bit of Twitter talk. Hundreds of thousands more got the message on Facebook, LinkedIn, and from the Today Show’s 3 million-follower Instagram account.

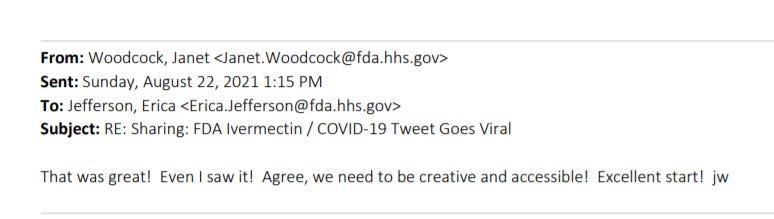

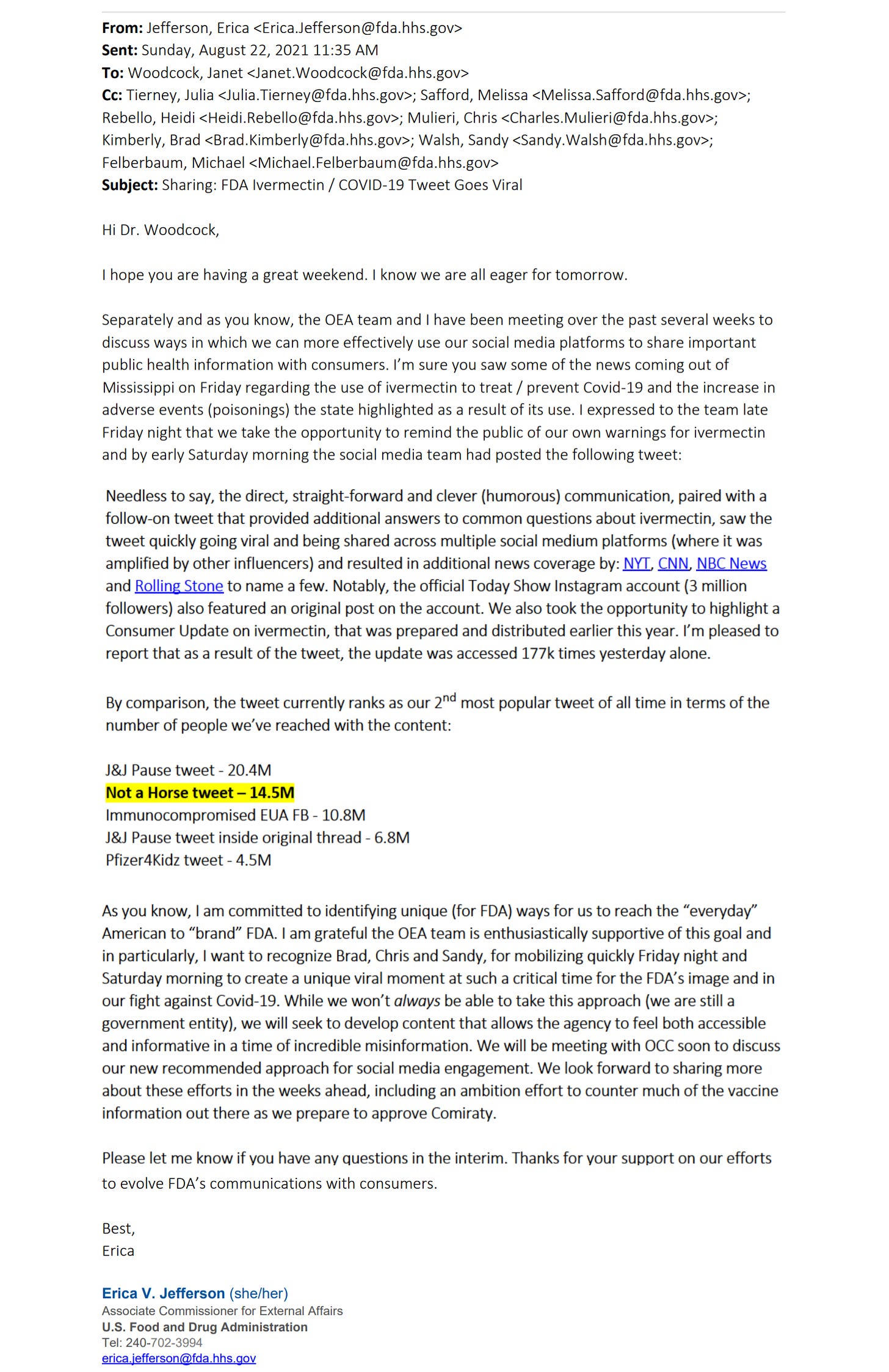

“That was great!” declared FDA Acting Commissioner Janet Woodcock in an email to her media team. “Even I saw it!” For the FDA, the “not-a-horse” tweet was “a unique viral moment,” a senior FDA official wrote to Woodcock, “in a time of incredible misinformation.”

There was one problem, however. The tweet was a direct outgrowth of wrong data—call it misinformation—put out the day before by the Mississippi health department. The FDA did not vet the data, according to our review of emails obtained under the Freedom of Information Act and questions to FDA officials. Instead, it saw Mississippi, as one email said, as “an opportunity to remind the public of our own warnings for ivermectin.”

The story behind the tweet that went ’round the world shows how a myth was born about a safe, if now controversial, human drug that was FDA-approved for parasitic disease in 1996 and bestowed the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2015. It is a story in which the barest grain of truth morphed into an anything-goes media firestorm.

It began with one sentence in a Mississippi health alert on reports to the state’s poison control center: “At least 70% of the recent calls have been related to ingestion of livestock or animal formulations of ivermectin purchased at livestock supply centers.” In the thick of a fierce covid wave in the American South, no official at the FDA, or reporter for that matter, seemed to ask: 70 percent of what? Instead, government and media joined forces against a public health threat that, in retrospect, was vastly exaggerated.

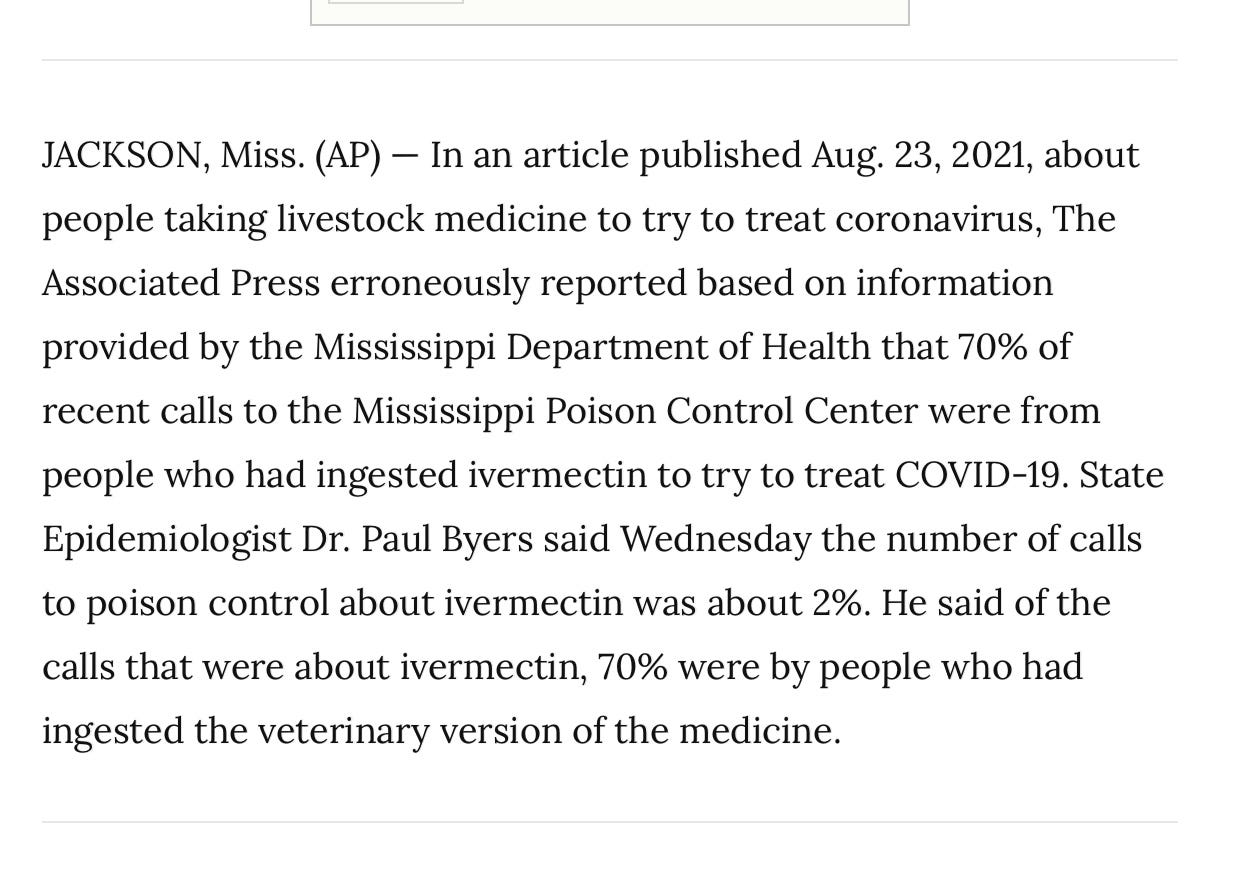

Amid dozens of articles that ensued, Rolling Stone told of Oklahoma hospitals so jammed with ivermectin overdoses that gunshot victims had to wait for care—except it wasn’t true. Twice, The New York Times printed corrections of the same false information from Mississippi, which it described in one article and later removed, as “a staggering number of calls.” The Associated Press, Washington Post and, twice, the The Guardian in London also corrected its reporting on the alert.

The Times’ correction summed it up: “This article misstated the percentage of recent calls to the Mississippi poison control center related to ivermectin. It was 2 percent, not 70 percent.” (The Times and Post both made corrections in direct response to our reporting for this article.)

In real numbers, six calls were received for ingestion of ivermectin. Four were for the antiparasitic drug given to livestock.

If ivermectin reports had indeed been 70 percent of calls in the twenty days covered by the alert, about 800 would have flooded the poison control line. Instead, eight came in. Two callers sought information. Five had mild symptoms. One was advised to seek further care, according to data from the Mississippi Poison Control Center.

Without question, people should not take drugs made for animals, given issues of dosing and medical oversight, to name just two. That much is clear.

But in hopping on the Mississippi bandwagon, the FDA achieved a long-standing goal separate from warning against livestock dewormer. It obliterated the line between the ivermectin that saved millions from river blindness in Africa and the worm-killing animal medicine that—“Stop it, y’all”—only the deluded would try. It turned ivermectin, which doctors and health ministers in several countries say has saved many from covid-19, into a drug to be feared, human form or not.

This highly effective bait-and-switch began last March with a webpage, to which the FDA tweet linked, that conflates the two ivermectins. On one hand, the FDA tells of receiving “multiple reports of patients who have required medical attention” after taking the animal product. On the other, it describes the fate awaiting people who take large amounts of any ivermectin, ending a long list with “dizziness, ataxia, seizures, coma and even death.” The medical literature, nonetheless, shows ivermectin to be an extremely safe medicine.

So how big was the surge that FDA described as “multiple”? Four, an agency spokesperson said just after the page went up. Three people were hospitalized, but it wasn’t clear if that was for covid itself. When pressed for details, FDA cited privacy issues, and said in an email, “Some of these cases were lost to follow up.”

This is how government gets away with some whoppers, and with the media’s help.

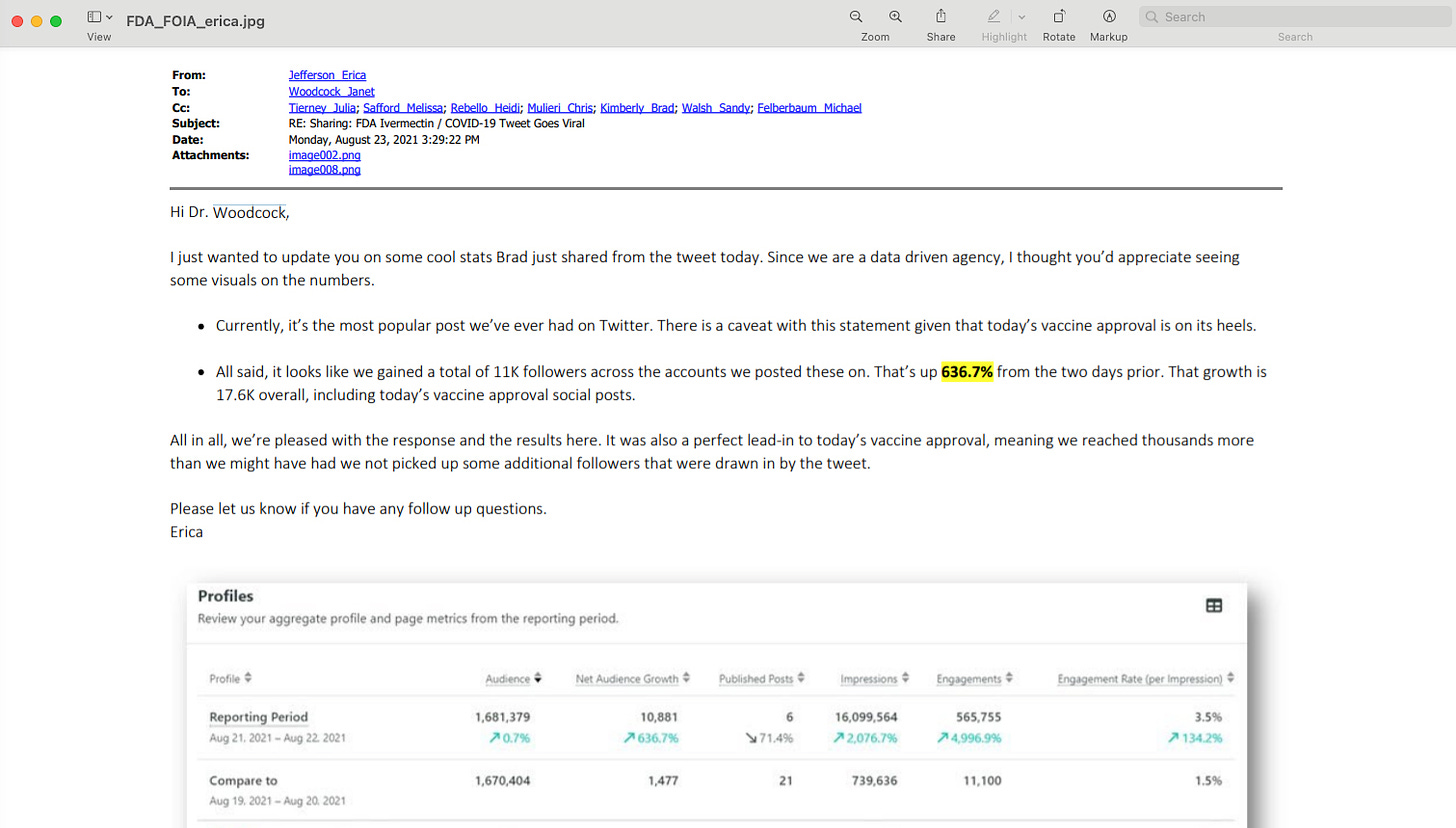

Below, FDA officials crow over the deception that was “the most popular post we’ve ever had on Twitter:”

…and the FDA commissioner was thrilled:

Within days of the tweet, headlines crowed, “Say ‘neigh’ to ivermectin,” while cable hosts and comedians riffed on “horse paste.” USA Today, ABC News, The Hill, Slate and NPR picked up the story. When CNN retweeted “not-a-horse,” FDA was gleeful. “The numbers are racking up and I laughed out loud,” wrote FDA Associate Commissioner Erica Jefferson in one email.

On October 5, forty-six days after posting, the Mississippi health department “clarified” its alert to say that 70 percent of ivermectin calls—not of all calls—were for the animal kind. The image of dread, however, lives on in archived stories that often used nifty but hardly accurate shorthand, like overdose or poisoning. In reality, ten of twenty-four ivermectin calls to the Mississippi center from July 31 to Aug. 22—40 percent—merely sought information, our reporting found, which is common to poison control centers. In 2019, poison control centers logged more than 47,000 reports for acetaminophen and 83,000 for ibuprofen.

In this email obtained by Linda Bonvie under the Freedom of Information Act, FDA officials celebrate reaching the “everyday” American with a tweet that sparked a media firestorm of lies:

Amid the hubbub, the Northern New England Poison Control Center posted a notice September 15 stating it had “managed 14 human exposures to ivermectin in 2021,” mostly in early September. “None of these patients experienced significant effects from the ivermectin.” Other states—Illinois, Iowa—have reported similar numbers.

This isn’t to minimize potential poisoning from the livestock drug. Mississippi officials told us of two people hospitalized after their flawed alert, including one intubated and in cardiac arrest. But like the FDA, Mississippi officials had no details.

The Associated Press issued this correction on their wildly inaccurate reporting:

In New Mexico, officials linked two deaths in September to ivermectin poisoning, contending later the victims took the drug and died “after delaying treatment for COVID-19.” The state’s acting health secretary, David Scrase, even said he was taking a “calculated risk” in announcing the first death on September 9 though tests would likely take weeks. No one questioned his widely reported conclusions.

This is the correction the New York Times was forced to make—twice—as a result of inaccurate poison control reports from the Mississippi State Department of Health:

In the pandemic era, mainstream reporting is characterized by firmly drawn narratives. One is that ivermectin is an unproven, possibly unsafe, treatment for covid, with several dozen supporting trials largely dismissed as small, biased, and lacking rigor. We would argue that the potential and effectiveness is far more nuanced and worthy of serious exploration.

This media landscape, which marginalizes, censors, and uses political or anti-vaccine labels, set a perfect stage for the Mississippi-inspired onslaught of anti-ivermectin hype. Some of it was true. Much was not, in particular the lasting image of peril of a drug celebrated as “astonishingly safe for human use” in a 2011 article. Last March, a safety review of ivermectin by a renowned French toxicologist could not find a single accidental overdose death in the medical literature in more than 300 safety studies of the drug over decades. The study was performed for MedinCell, a French pharmaceutical company.

Since 1992, twenty deaths have been linked to inexpensive, off-patent ivermectin, according to a World Health Organization drug tracker called VigiAccess. By contrast, since just the spring of 2020, 570 deaths have been linked to remdesivir, an expensive, patented covid drug. The question is why remdesivir is being used at all, with a WHO recommendation against it and a new Lancet study finding “no clinical benefit.”

The other question is why ivermectin is not. The FDA tweet arrived just as ivermectin prescriptions were soaring, up twenty-four-fold in August from before the pandemic. These were legal prescriptions written by doctors who, presumably, had read the studies, learned from experience, and decided for themselves. Indeed, 20 percent of prescriptions are written off-label, namely for other than an approved use.

The effort to vilify ivermectin broadly has helped curb the legal supply of a safe drug. That’s what drove people to livestock medicine in the first place.

Comments

Post a Comment