The Bizarre Biology of Birds

The Bizarre Biology of Birds

A detailed look at one of nature's strangest experiments

Stone Age Herbalist

“Here also I first met with the pretty Australian Bee-eater (Merops ornatus). This elegant little bird sits on twigs in open places, gazing eagerly around, and darting off at intervals to seize some insect which it sees flying near; returning afterwards to the same twig to swallow it. Its long, sharp, curved bill, the two long narrow feathers in its tail, its beautiful green plumage varied with rich brown and black and vivid blue on the throat, render it one of the most graceful and interesting objects a naturalist can see for the first time.”

-Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, Vol I

If you’re anything like me then birds are one of those perennial, permanent obsessions. The kind of obsession that lasts a lifetime, and continually rewards you for your perseverance. One simple conclusion from this love affair is that birds are truly very strange. Creatures that live amongst us every day, in every habitat, that sing, that fly, that swim, dive and walk, creatures that range from the exquisitely drab to the sublimely beautiful in appearance, and are constantly watching us. Everything from their bone structure to their brains is different to ours, and much of their lives remains a mystery to us.

Somewhere around 66 million years ago life on earth underwent one of its most famous rearrangements. The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event resulted in the annihilation of the dinosaurs, themselves one of nature’s most interesting experiments in body shapes, behavioural adaptations and charisma. As most schoolchildren know, the only surviving lineage of these beasts became the ancestors of modern birds. In fact, three major groups of these dinosaurs seemed to pass through this event: the Palaeognathae, the ancestors of ostriches, emus, cassowaries and other ‘primitive’ birds; the Galloanserae, the group containing fowl and waterfowl, and the bizarre Neoaves, who constitute the other 95% of living bird species. Whilst the former two groups had already diverged prior to the K-Pg asteroid collision, the Neoaves suddenly exploded into wildly diverse families and forms as the rest of the dinosaurs died away. Today the Neoaves are classified under the charming lineage titles of ‘The Magnificent Seven’ and the ‘Three Orphans’. The physical space in the world and the opportunities it offered suddenly opened up to a group of flying animals which rapidly took advantage of every niche.

Whilst I don’t want to overly personify something as abstract as an evolutionary lineage, I do want to use the language of ‘will’ and ‘intention’ to describe the life paths that these new animals took. They moved away from the logic of lizard life, and instead drove themselves into novelty through three main vectors, in my opinion anyway. These were:

The freedom to move

The freedom to see

The will to beauty

Each of these will be broken down in turn, but a side point - birds were not and are not the only creatures to make use of flight, even during the age of the dinosaurs. They are however the only surviving creatures to combine feathers with flight. The Scansoriopterygidae dinosaurs of the Jurassic era had bat-like membrane wings for gliding and perhaps flying; the feathered Microraptoria should be better known for potentially using four wings, and the early Cretaceous Caudipteryx could turn out to be a feathered dinosaur which became flightless over time. But none of these managed to flourish like the ancestors of modern birds did.

The Freedom To Move

The most obvious thing about birds is that they can fly. But they can also dive, hover, swim on and under the surface, run, hop and jump, climb, walk, burrow, wade and glide. In fact, their range of motion is truly astonishing, limited only by their shoulders, two legs and lack of digits. Going further though, these movements are not just utilised but mastered. Peregrine falcons can dive at their prey with speeds of over 300km per hour; swifts can spend entire seasons in the air, sleeping on the wing; emperor penguins have been known to dive underwater to over 500m and hold their breath for 15 minutes; ostriches can run for long periods at 50mph; bar-headed geese can fly with ease over Mount Everest, and a five month old bar-tailed godwit recently flew non-stop from Alaska to Tasmania - a world record of 13,560 km.

To gain such mastery, birds have developed one of the most sophisticated suites of locomotion of any living species on earth. These include:

Hovering and ‘kiting’, back-hovering and reverse flight, ‘helicoptering’ and hover-gleaning

Cursorial foraging, flock synchrony

Striking, kicking, stamping

Sea-anchoring, surface-skimming and sand-swimming

Swooping, wing & foot propelled diving and plunging

Dynamic, thermal and static soaring

Tail-supported vertical climbing, beak-assisted climbing, head-first descending

Lekking dances, coordinated rushes

Flutter-diving, parachuting and flutter-down displays, sky-dancing and wing-clapping

Aerial acrobatics and courtship displays (rolling, tumbling, dropping-and-catching, winnowing, snaps, inverted hangs, pendulum flights and chase flights)

Wing-assisted incline running (WAIR)

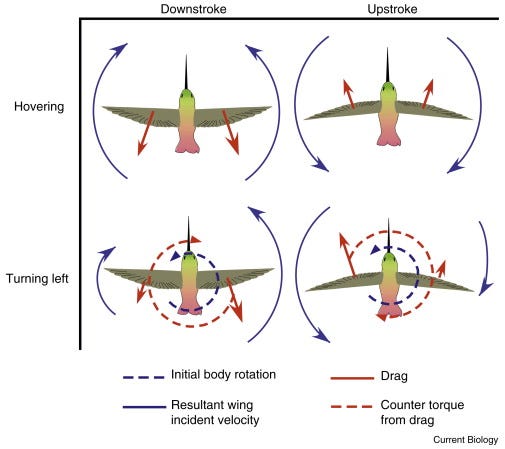

To focus in on just one of these - hummingbird hovering - is to show just how far birds explored and innovated within the evolutionary space of movement. Hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are a New World bird species that decided to develop the capacity for hovering flight, a hover so precise and controlled that they could feed on sugary nectar within plants. The sugar is essential to feed their explosively high metabolic rate, and maintain the roughly 80 wingbeats per second generated from their huge pectoralis and supracoracoideus muscles. Uniquely hummingbirds generate lift on the wing upstroke as well as the downstroke, by rotating the wing each figure-of-eight cycle. For those of you interested in metabolism - the muscles of the hummingbird wings are fast oxidative-glycolytic fibers (type IIa), with giant mitochondria occupying around 50% of total cellular volume. This speed and style of wingbeat produces the distinctive humming sound as the bird merrily flies around, one of the biological wonders of the world.

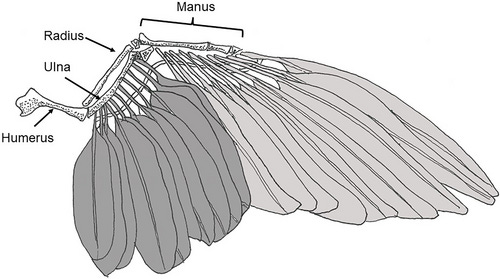

Of course, to really describe the adaptations of birds we have to look at feathers. These oddities arrived around 200 million years ago first as simple filaments. Feathers are made up of keratin and typically come in two forms - down feathers and vane feathers. The central rachis of the feather supports orthogonal barbs, sometimes highly coloured, other times not. Vane feathers on the wings (remige feathers) are further broken down into primary, secondary and tertials, and tail vane feathers (retrices) also have the same similar stiff morphology, with interlocked barbs. Down feathers, plumes, filoplumes, bristles and other specialised feathers also exist. Since the function of feathers varies widely between species (camouflage, flight, mating attraction, waterproofing, warmth, sound production), types of feather and their unique structures also change.

With feathers and wings comes the need for a much higher metabolic rate and decreased mass, to make flight efficient. This is achieved through a number of specialised changes to the vertebrate body. Firstly birds have many hollow bones, that is to say the interior of the bone is devoid of marrow or bone cells, but often contains internal struts and supports. The skeletal structure works perfectly with the second adaptation - the astounding avian respiratory system. Bird lungs are not the expanding bellows of mammals, but rather a rigid assortment of front and rear air sacs connected by parabronchi. When the bird inhales, fresh air is drawn the rear or posterior sacs, and as the oxygen gradient alters and the bird exhales, this air moves to the front or anterior sacs, before finally being expelled. In this way there is no mingling of old and fresh air, as with mammals, and the air is circulated in one direction only. The gains from this system are incredible, birds are roughly ten times more efficient at oxygen uptake than mammals. This system of air sacs can also in some birds extend into the bones themselves, combining with the skeletal system to maximise metabolic output with minimal weight. The core body temperature of birds is also typically between 39 and 43 degrees, reflecting this engine of oxygen turnover and the constant muscular activity of flight.

Arguably the most crucial evolutionary feat to allow for bird flight, the wing is a system in which the skeleton and feathers act together to allow for a high lift-to-weight ratio. The wing skeleton is particularly lightweight; unlike terrestrial vertebrates’ marrow-filled bones, most bird wings are composed of hollow bones, similar to the bones of bats and pterosaurs [7]. These hollow (pneumatic) bones connect to the pulmonary system and allow air circulation which increases skeletal buoyancy…

The wing skeleton and flight feathers work together to form an airfoil that supports the bird's mass in flight and undergoes torsional and bending forces while maintaining a minimum weight. Both wing bones and feathers have a thin, dense exterior with reinforcing internal structures, efficiently tailored for the specific bird, and a composite microstructure. The coinciding design principles between these features reveal an apparent evolutionary trend toward structures that efficiently resist bending and torsion.

-Extreme lightweight structures: avian feathers and bones (2017) Sullivan et al

By shedding excess weight such as teeth, jawbones, heavy marrow-laden skeletal structures, and developing a massive rigid respiratory-skeletal system - birds have been able to take advantage of the feathers gifted to them by their dinosaur forebears and colonise practically every environment on earth. Movement for birds, the freedom to move, means the freedom of the sky, land and sea; it means making homes on cliffs, in trees, the tops of buildings; it means shrinking themselves down to take advantage of insect food sources; it means the liberty to migrate away as the weather changes and to utterly dominate their world of the air, with speed and graceful motion.

The Freedom to See

Such a creature which excels at moving through space should of course develop an ultra high sensitivity to their surroundings. Bats use echolocation, arachnids use vibration, and birds use sight. But as we’ve already encountered, bird sight, like movement, is about pushing evolutionary capacity to its limits and mastering the field. Birds in their totality have:

The highest visual acuity of any animal

UV light detection

An extremely high field of vision

The capacity for night vision/low light hunting

Very high flicker-fusion frequency processing power (can see in slow motion)

Polarised light detection

Magnetic field detection

Multiple adaptations for eye protection while diving, pecking wood

Aquatic vision

If the bird body developed to fly, then the bird brain and head developed to see. Some birds are so good at this, they have been described as ‘eyes with wings’. Avian eyes often occupy over 50% of their cranial volume (humans clock in at around 5%), and they are shaped differently - often flatter, with the lens brought forward. Bird eyes are secured more rigidly, can move independently and use a third membrane (nictitating eyelid) to keep the surface lubricated rather than blinking. Birds prefer to move their whole head rather than swivel their eyeballs in their sockets, but their field of vision is often vast:

The avian species with the greatest field of vision is the American woodcock (Scolopax minor). Its eyes are positioned exactly opposite of each other, allowing it an astonishing horizontal visual field of 360° and a vertical field of vision of 180°, which enables it to quickly scan its surrounding area with out moving its eyes or head. Martin reports the horizontal visual field of the mallard duck (Anas platyrhynchos) to also be 360°, with a binocular field of approximately 20°

-Avian Vision: A Review of Form and Function with Special Consideration to Birds of Prey (2007) Jones et al.

Avian photoreceptors within the eye are far more sensitive than mammalian eyes. They typically possess six types of photoreceptive cells on the retina, compared to our four. Their possession of four cone cells for processing colour, along with specialised oil droplets within the retina, means birds are tetrachromatic and some species like the zebra finch can perceive ultraviolet light.

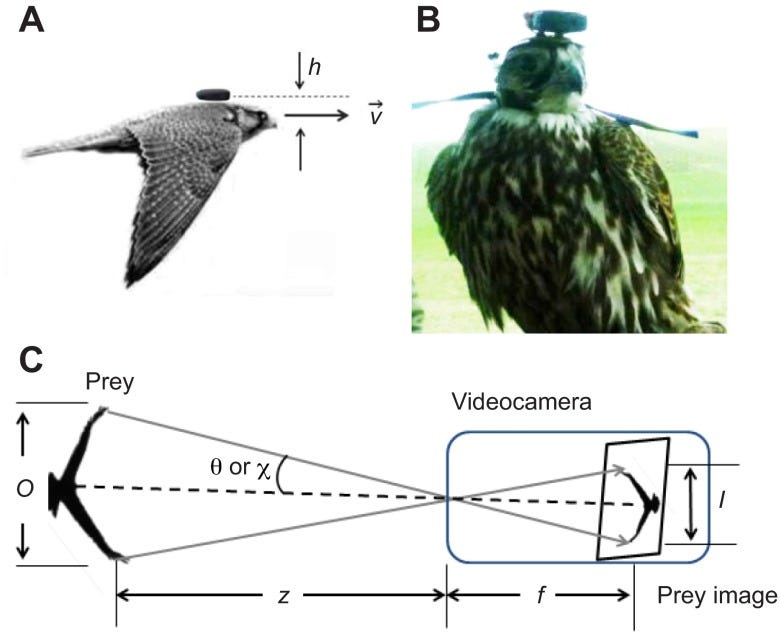

Avian retinas also often show a depressed pit called a fovea which allows for the denser packing of photoreceptor cone cells and higher visual acuity when incoming light is focused onto these cells. Some birds such as raptors, swallows and pigeons have two foveae, which gives them immense powers of sight while flying. To illustrate lets look at the peregrine falcon. The falcon has two foveae per eye, one forward angled for binocular vision, the second angled laterally for long distance monocular vision. These are very densely packed with cone receptors (approx one million per mm²), roughly 2 to 3 more than in humans. Falcons can easily spot prey like rabbits from miles away, first utilising their monocular resolving power, then descending with a logarithmic spiral pattern to keep the prey within their monocular fovea. Finally, sometimes approaching speeds of over 300km/hour, the falcon will roll or bank to switch to binocular vision, providing more accurate depth perception as its brain calculates the necessary acceleration and adjustments in wing and foot placement to catch their next meal.

Another feature which allows falcons and other birds to operate so effectively at such high speeds is their ability to still see frames of motion, even at very high speeds. This processing power is known as the flicker-fusion threshold, or rate. Humans can perceive flickering light bulbs at a rate of below 60 Hz, after which they become a single continuous image. Birds can still detect the flicker at 80-100 Hz (songbirds, pigeons), up to 120 Hz (hummingbirds), and falcons up to 129 Hz. What we would perceive as a colourful smear or blur, the falcon observes like a slow motion film. The density of photoreceptor cells, combined with their eyeball shape, lens placement, additional cones/oil droplets, foveae and eye placement gives different bird species immense flexibility. Owls and other low-light species such as nightjars, petrels, shearwaters, bitterns and kakapos, have huge eyes packed with rod cells, along with specialised neural processing capabilities for light contrast. Birds that hunt underwater such as penguins, gannets, cormorants, kingfishers, loons and grebes make use of powerful, spherical lenses with strong muscles for instant focusing, as well as employing their nictitating eyelids as protective goggles.

One final mention must go to the humble pigeon and compatriots for their almost science fiction-like ability to actually see magnetic fields. Specialised proteins called cryptochromes have been discovered in certain bird photoreceptors; four types of cryptochromes—Cry1a, Cry1b, Cry2 and Cry4—have been found in pigeons and migratory passerines. Complex quantum biological mechanisms have been proposed for how these work, but at present it seems certain that some birds can fly across huge distances in part guided by the earth’s magnetic fields. Thus again, like with movement, birds seem determined to pick a family developmental route and drive evolution into previously unknown forms of mastery. Theorists of motion have discussed how birds and humans differ in their perception of the world - our egocentric forward facing vision with the sensation of stepping into reality, while birds with their vast and lateral fields of vision experience themselves moving through the world.

The Will to Beauty

To cram all this into a single article I have had to leave out many other fascinating avian features, such as their intelligence and sociality, how they forage and hunt for food, and their fascinating life-cycles. Bird mate selection and breeding is full of curiosities - their monogamy, lek performances, parental investment, and the arms race between parasites and their hosts (cuckoo!).

I have subsumed much of these behaviours, and more, under the concept ‘the will to beauty’, which I feel captures the overall avian push towards song, dance, theatre, performance, colour and costume. Birds are not subtle creatures, they have Apollonian tastes in exteriority. Bird song is not a pale imitation of human song, on the contrary birds have mastered the art. Their vocal syrinx, not larynx, provides them with the capacity for multiple notes simultaneously, for syllables, warbles, chirps, sustained tones, trills, clicks, whistles and harmonics. They can sing in duets, in groups and alone, as part of territorial defence or to attract a mate. The specialised neural circuitry which helps them memorise thousands of songs also helps with learning new songs, a process which leads to distinctive musical subcultures within the same species. Many birds are also outstanding mimics, uncannily replicating everything from chainsaws to human speech, car alarms to guitar solos.

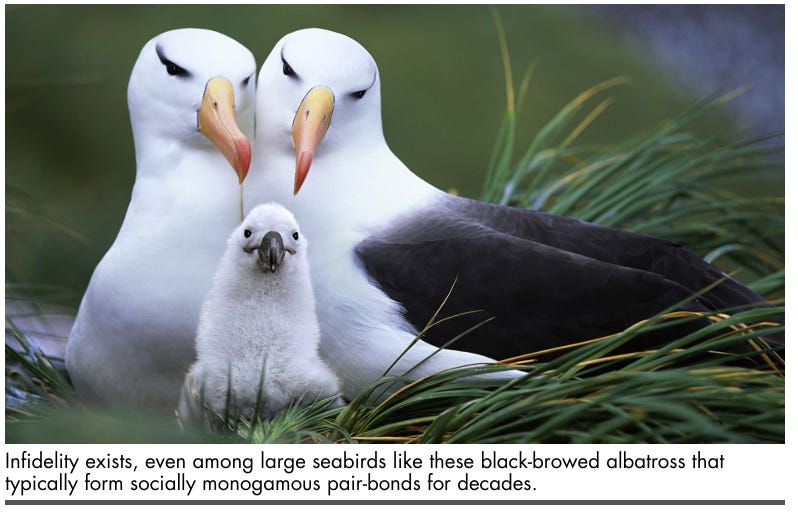

Song naturally accompanies dance and performance. Everyone by now has seen the wonderful and alien courtship rituals of the birds-of-paradise, with their highly specific tutu-like plumages or striking eye patterns on their raised tails - but they aren’t the only ones. Birds all over the world perform acrobatics (mannakins), object tossing, synchronised ‘rushing’ (grebes), graceful ballet duets (cranes), ritualised beak tapping and head bowing (albatrosses) and many other rehearsed solo or group performances. Some bird species have to practice these dance moves for years as male juveniles, in the hope of attracting female attention. Many go beyond just dance, and use props, architecture, precision footwork and coordinated wing/tail motifs in some of nature’s ultimate courtship performances. Look up videos of grebe water dances, parotia’s ballet, the argus pheasant display or the bower bird’s eye for colour.

As we’ve seen with their visual adaptations, birds love colour. Therefore it makes sense that birds are arguably the most visually dimorphic family of animals on earth. The sexual theatre of avian life extends into every part of the male bird (as a generalisation). Males often show radically different colour and feather schemes to their female counterparts, theorised as the classic example of ‘runaway sexual selection’

One of the side effects of coating a body with feathers is that it provides a perfect canvas for decoration. Birds may have found practical uses for these stiff keratin bristles, but one could be forgiven for thinking that their primary function was personal ornamentation. They might be mostly eyes with wings, but this results in a natural race of aesthetes, gifted with almost divine powers of sight and adorned with a miraculous tapestry for experimental colours, patterns and motifs. Add to this their capacity for song, theatre and speed, and they seem in aggregate profoundly alien. Even their intelligence and mischievous sense of humour arises from a radically different brain, complete with a convergent frontal lobe (nidopallium). Their dinosaur ancestors renounced their claim to world dominance, so birds pursued other paths of mastery and pleasure.

Sometimes beauty is the glorious but meaningless flowering of arbitrary preference. Animals simply find certain features — a blush of red, a feathered flourish — to be appealing. And that innate sense of beauty itself can become an engine of evolution, pushing animals toward aesthetic extremes…

Birds transformed what was once mere frippery into some of the most enviable adaptations on the planet, from the ocean-spanning breadth of an albatross to the torpedoed silhouette of a plunging falcon. Yet they never abandoned their sense of style, using feathers as a medium for peerless pageantry. A feather, then, cannot be labeled the sole product of either natural or sexual selection. A feather, with its reciprocal structure, embodies the confluence of two powerful and equally important evolutionary forces: utility and beauty

-How Beauty Is Making Scientists Rethink Evolution (2019) Ferris Jabr

This theory, that beauty is an evolutionary force in its own right, is one I will be exploring further in future writing. Until then, go outside and watch some birds!

Comments

Post a Comment