Vascular Symptoms Caused by COVID-19 are Utterly Unique and Unusual... Just Like Every Other Respiratory Pathogen Ever

Vascular Symptoms Caused by COVID-19 are Utterly Unique and Unusual... Just Like Every Other Respiratory Pathogen Ever

Like many others, the authors participate in a WhatsApp Group with other writers and commentators on the covid event. One point of contention - which fairly frequently arises - is whether a distinct and novel disease called ‘covid’- caused by a novel virus (SARS-CoV-2) - really exists, or whether (as the authors believe) the purported novelty is in fact merely a mirage caused by observation and reporting bias.

In support of the novelty trope, one colleague claimed that the key difference between ‘covid’ and other influenza-like illnesses was that covid had distinctive vascular effects, and cited a number of scientific papers in support.

We decided to review the literature, including the papers our colleague cited, with a view to critically analysing the extent to which the available evidence supports these claims.

Young people are getting blood clots from Covid!

One of the key pillars of evidence frequently deployed to support the trope that Covid-19 is both a unique and an unusual disease distinct from regular colds and influenza-like illnesses is that the SARS-CoV-2 virus does not merely cause a respiratory disease, but that it also causes severe vascular disease. And does so in young people.

Reports and anecdotes of young people being admitted to A&E with shortness of breath were accompanied by stories of blood clots, in the lung and elsewhere, often discovered post-mortem. Given these reports have tended to be of younger people, rather than in the elderly, it was perceived as all the more shocking and suggestive of something uniquely novel and deadly in circulation.

The kinds of vascular problems widely reported included endothelial injury, increased arterial stiffness, and widespread microthrombosis. Specifically, articles published in 2020 reported increased coagulation markers (like D-dimers), inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction leading to vascular leakage and thrombosis. Stroke caused by large-vessel occlusion was also documented in younger Covid-19 patients, underscoring the unusual vascular risks linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection. These findings highlighted Covid-19 as not just a respiratory disease but one significantly involving vascular pathology, even in younger populations without pre-existing cardiovascular disease.

Likewise, vascular problems are a key symptom, in a very long list, said to be characteristic of so-called long-covid, in relation to which vascular abnormalities were claimed to have appeared early and sometimes persisted for months after infection, even in mild or asymptomatic cases.

Embedding the narrative

We first reported on covid and ‘blood problems’ in our 2023 article on spikeopathy, a term widely used by the alternative medical community to characterise the novel pathogenic effects of SARS-CoV-2 in both covid, long-covid and vaccine injury1. That article dismantled many of these claims but barely touched on the ‘vascular issues’ investigated here, except to say that out of all of the papers reporting covid symptoms at that time we reported on only two papers that reported vascular issues: Cleverly et al and Klok et al. In that article we said:

“Symptoms related to DAD (diffuse alveolar damage), microvascular thrombosis (micro clotting), alveolar haemorrhage are not consistently reported, with only the one Dutch study and the Kory paper both citing it as a specific finding related to Covid-19.”

We were wrong not to challenge the vascular claims earlier. Given more time and study we would have found more articles, but at that time we were focused on other supposedly unique aspects of Covid-19, mainly related to pulmonology, radiology and CT-scans.

However support for this narrative has been carefully embedded in the academic literature via a number of studies, rushed to publication in ‘reputable’ journals in Spring 2020, including:

Wichman et al (Germany) reported on the post-mortem findings of a series of 12 ‘Covid-19–positive’ deceased patients who suffered thrombotic complications; 58% (7 in 12) of these had suffered DVT (Deep Vein Thrombosis) which had not been suspected during life; in 4 cases it was found that a massive pulmonary embolism caused death. However there was no comparison against non-Covid patients and testing for competing pathogens was not undertaken. Likewise, no information about what treatment the subjects had been subjected to was given.

Carsana et al carried out autopsies on 38 deceased Italian Covid patients, focusing on pulmonary lesions. They reported widespread diffuse alveolar damage and claimed that the predominant pattern of lung lesions in patients with Covid-19 is diffuse alveolar damage, as described in patients infected with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronaviruses.

Notable scientific failings by Carsana et al related to bacterial and fungal infections. They admitted that “four (11%) patients also had bacterial abscesses (one or two per lung, …), and one (3%) had a single fungal abscess... The abscesses were presumed to have formed after hospital admission.” This suggests a proclivity to dismiss any possible alternative explanations for the findings other than ‘Covid’.

They also state that “...[only] in cases with histological suspicion for bacterial or fungal infections, periodic acid–Schiff staining and Grocott methenamine silver staining were done to confirm morphological findings…..”, implying that no systematic testing for bacterial infection was done ante mortem.

Ackerman et al reported on the apparent pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis found in Covid-19 patients who died during the peak ‘pandemic’ period in Italy. They studied 7 lungs in covid patients, 7 with ARDS secondary to influenza, and 10 age matched uninfected control lungs. They found that covid patients had severe endothelial injury, widespread vascular thrombosis with microangiopathy and occlusion of alveolar capillaries. Reporting the “presence of distinctive pulmonary vascular pathobiologic features in some cases of Covid-19” and that “our finding of enhanced intussusceptive angiogenesis in the lungs from patients with Covid-19 as compared with the lungs from patients with influenza was unexpected“. They offered no comment on whether any testing was done for competing pathogens in any of the patients studied.

Maise et al carried out a systematic literature review, including some the studies mentioned here, and found a high incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism among Covid-19 decedents, but that in some of the studies reviewed secondary bacterial pneumonia was reported.

Rapkiewicz et al (USA) reported on 7 covid patients in whom thrombi in pulmonary, hepatic, renal, and cardiac microvasculature were observed. All lungs exhibited diffuse alveolar damage (DAD). All hospitalized patients were mechanically ventilated. They claimed that ‘renal findings’ ‘shed light on the pathogenesis of acute kidney injury in Covid-19’ and that ‘virions were observed in proximal tubular cells’. Again, however, there was no comparison against non-Covid patients, no tests for competing pathogens, and no information on what treatment they received.

Unfortunately, these papers suffered from the same fundamental flaws:

Small sample sizes;

Disease symptoms were attributed to SARS-CoV-2 based merely on a positive ‘covid test’;

No other testing was conducted for competing pathogens, such as influenza or bacterial infections causing pneumonia;

Little to no consideration was given in almost all of the papers as to the treatment regime provided (or not provided) to the patients;

In the majority there was no comparison against a control group, either of post-mortem samples of people free of disease, or from infected tissue samples from patients who were said to have died of bacterial or viral infections.

Is Covid-19 really so special?

Is Covid-19 disease so unique and special? Are the vascular sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 genuinely novel, or is there any historical evidence that these symptoms can be caused by other viruses, such as influenza, or indeed are consequential effects of bacterial pneumonia or even fungal infection?

Broadly speaking there is a lot of available evidence of microvascular thrombosis and alveolar hemorrhage in bacterial pneumonia. The papers we review below show that pre‑covid and contemporary literature shows that acute lower respiratory infections—viral and bacterial—can trigger in situ pulmonary thrombosis through inflammation‑driven endothelial injury and hypercoagulability. Several reviews note that thrombotic complications (arterial and venous) have long been recognized in pneumonia, with pulmonary artery branch thrombosis reported even under prophylactic anticoagulation; however, granular, bacteria‑specific microvascular clot burden data are limited.

Cui et al (2021) reported that of 90 patients with ARDS caused by bacterial pneumonia - 40 out of 50 had DVT (80%). This exceeds the 58% for Covid-19 reported by Wichman et al and, moreover, the study has a much larger sample size.

A case report written by Schmitz et al (2021) describes a young patient, 28 years of age, who presented with significant haemoptysis (coughing up blood), eventually diagnosed as bacterial pneumonia. They noted that:

“Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common bacterial pathogen that causes atypical community- acquired pneumonia. Illness onset can be gradual and progressive over weeks. Patients typically have cough, pharyngitis, malaise, and tracheobronchitis. Although symptoms are frequently mild, the initial presentation can be severe with numerous complications. We present a case of a 28-year-old male who presented with 1 day of significant hemoptysis. He was intubated for airway protection and underwent bronchoscopy, which showed multiple blood clots in several lung lobes, consistent with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). His workup was negative for pulmonary embolism, coagulopathy, and vasculitis. He tested positive for rhinovirus and mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM (negative IgG). He was ultimately discharged home with oral doxycycline to complete a 10-day course. DAH is a rare presentation and life-threatening complication of mycoplasma pneumonia. Although there is a reported association between DAH and rhinovirus, our patient improved with antibiotics making mycoplasma pneumoniae the likely culprit. When encountering hemoptysis or alveolar bleeding, clinicians should have low suspicion for atypical infections and start appropriate antibiotics early in the clinical course.“

A significant and thorough review, with over 200 references, by Babinka et al (2024) published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine sums up the known literature. Their conclusions are so informative that it is worth listing the key findings blow-by-blow:

“As thrombotic complications of infectious respiratory diseases are increasingly considered in the context of Covid-19, the fact that thrombosis in lung diseases of viral and bacterial etiology was described long before the pandemic is overlooked. Pre-pandemic studies show that bacterial and viral respiratory infections are associated with an increased risk of thrombotic complications such as myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, pulmonary embolism, and other critical illnesses caused by arterial and venous thrombosis.”

“A search for “(respiratory infection) AND (thrombosis)” yields over 7.5 thousand studies. However, the vast majority of sources are dedicated to thrombosis in COVID-19, while the number of studies not related to COVID-19 “((respiratory infection) AND (thrombosis)) NOT (COVID-19)” was 2477 at the time of the search. The final number of papers selected for this manuscript was 223, with the consensus of the authors.”

“The hypothesis of an association between acute infectious diseases and stroke has existed since the late 19th century.”

“Most clinical studies assume that a thrombus in the branches of the pulmonary artery is caused by thromboembolism from the deep veins of the lower extremities. However, there is increasing evidence that de novo thrombosis in the pulmonary arteries can occur even in the absence of DVT. The possibility of in situ thrombus formation in the pulmonary arteries without deep vein thrombosis (DVT) has been demonstrated in studies conducted both during and before the COVID-19 pandemic.“

“It is important to consider that other papers looking at VTE (venous thromboembolism) in COVID-19 may have overestimated rates of VTE, including thrombosis in situ as PE (pulmonary embolism).”

“… when the complication rates for COVID-19 (89,530 patients) and influenza (45,819 patients) were compared, myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation were less common in COVID-19 patients than in influenza patients.”

“When studying thrombosis in the context of infection, it is important to recognize that D-dimer is a nonspecific acute phase reactant….The same morphological changes in the endothelium of pulmonary vessels are also detected in ARDS of non-COVID etiology.“

“The high prevalence of early-onset bacterial coinfection was observed among patients with severe COVID-19. Based on autopsy protocols and morphological studies of the lungs of COVID-19 patients who died, we found an association between thrombotic complications and the histological evidence of bacterial infection of the lung.”

“…the early detection and treatment of bacterial co/super infection may help reduce the inflammatory response …., which is important for preventing thrombus formation in acute respiratory infections.”

“All of the thrombotic mechanisms described in COVID-19 were discovered in pre-pandemic studies of ARDS in viral respiratory infections and bacterial pneumonia. The novelty of the virus, the high morbidity, and the global scope of the problem prompted a large number of studies, most of which were interpreted as COVID-19-specific. However, there is currently no conclusive evidence regarding the specificity or uniqueness of COVID-19 pathogenesis.”

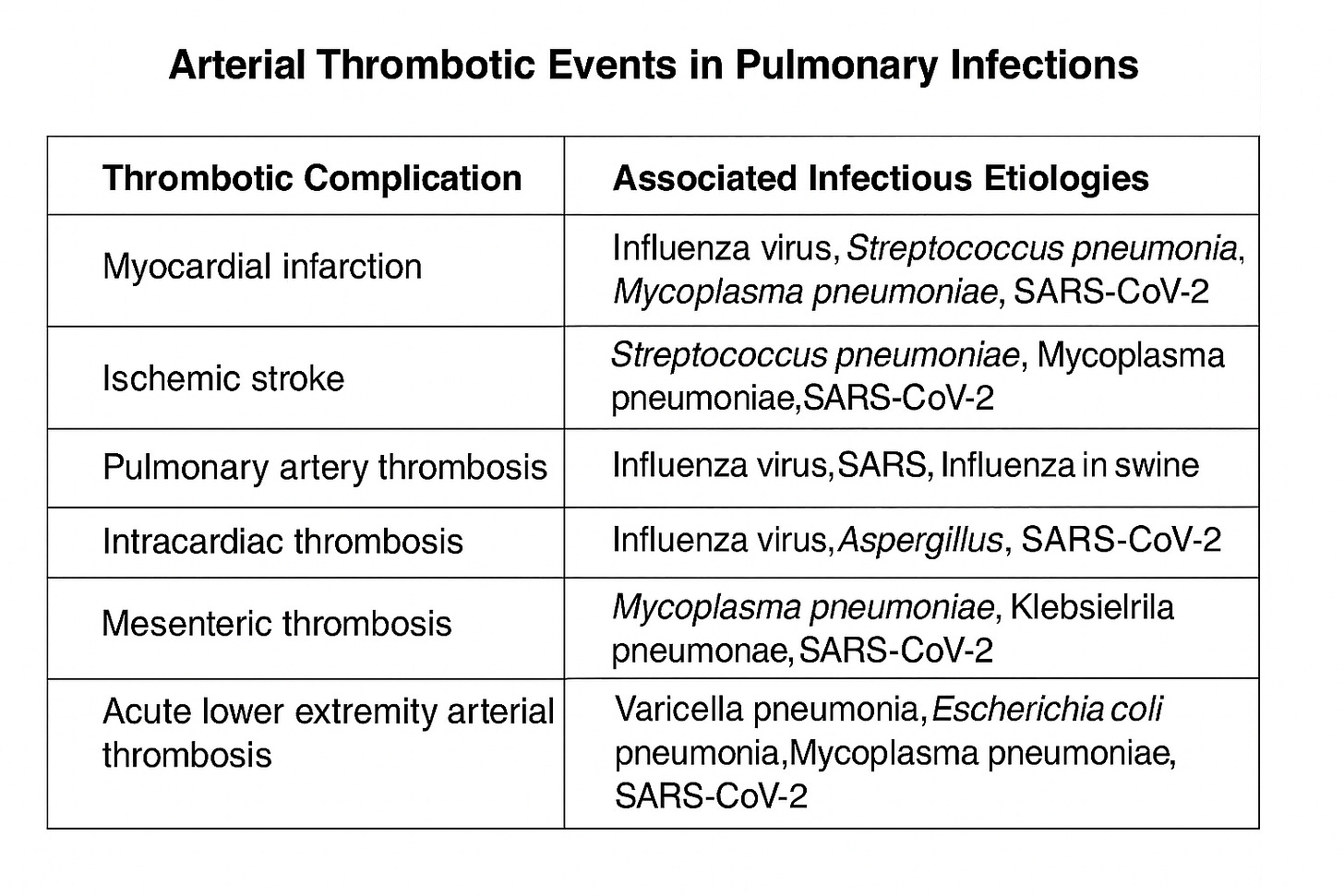

They summarise the role played by various pathogens (in arterial thrombotic events) in this table:

Concluding remarks

A review of the literature has revealed that the studies which are cited in support of the notion that covid is (uniquely) a vascular - as well as a respiratory - illness all suffer from one or more critical faults.

Firstly, they all rely on a ‘positive covid test’ to identify a patient who died from covid. We think most people are now well aware of the over-sensitive and non-specific nature of all the tests used during the covid event; yet this seems to have eluded the authors of these papers. This means that (for example) patients dying from advanced malignancies who happened to ‘test positive’ are amongst those whose lungs are said to be typical of patients dying from covid, even though the test result might well be an incidental finding.

Secondly, many of the studies are uncontrolled, in the sense that the authors have not looked for, using the same methodology, the same findings in those who died without positive tests for covid.

Thirdly, tests for competing explanations - mainly other infectious pathogens - were not generally performed. This is despite established evidence that - if looked for - multiple pathogens can be found in association with respiratory infective illnesses. Thus it cannot be said that other pathogens were not the cause of the clinical findings observed.

Finally, the literature is replete with evidence that the vascular findings which are described in relation to covid, and which are claimed to be unique to it, are anything but. They have frequently been observed in association with a range of other respiratory and non-respiratory illnesses. It seems surprising to us that claims of uniqueness have been made so readily and by so many authors, none of whom appear to have made even a rudimentary search of the pre-covid literature.

Taken together, the above leads us to conclude that there is no foundation to the claim that covid was a novel disease caused by a novel virus (SARS-CoV-2) which was distinguishable from other respiratory illnesses due to its pathological effects on the vascular system.

It is worth noting that we are not discussing the effects of vaccines on vascular injury or death in this article.

Source: Where Are The Numbers?

Comments

Post a Comment