Manipulative Interpretations of Trial Statistics

Manipulative Interpretations of Trial Statistics

The Chloroquine Wars Part CVI

"If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it."

-Joseph Goebbels

On a distant planet, in a galaxy far far away, the 2022 Final Four of the NCAA men's basketball (March Madness) tournament was hosted in Seattle Washington. Bill Gates sponsored the event, including a sideshow featuring the two finalists in an international search for the best unknown 3-point shooter. The sideshow sold as many tickets as did the games.

Emoji One, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The rules of the side event stated, among other things,

"The player who proves to be the better 3-point shooter at the end of the final event wins one million dollars."

One of the two final contestants was Pfred Pharmangton, Seattle's hometown hero. The 17-year old was set to attend UNC in the Fall of 2022 having obtained a fake vaccine card to go with his scholarship offer. Pharmangton rolled with an impeccable wardrobe, and his parents paid hundreds of thousands of dollars per year to have the best coaches work with him. While experts disagreed over whether he would be first round draft material in the 2023 National Basketball Association (NBA) draft, his parents' publicists managed to drive some Pharmangton jersey sales in China after an exhibition trip with the U.S. 18-and-under hoops squad. The million dollars would pay for some epic vacations for Pharmangton and his chosen friends during his likely one year as an undergraduate Women's Studies major.

The challenger was relatively unknown to the crowd, but not to NBA scouts who debated only whether he would be drafted first or second whenever he decided to make the leap. Southern California's Brian Tyson, known by friends as "the long range Honey Badger", was the early favorite in Vegas, despite a name that wasn't on the lips of the television commentators. In fact, all of the analytical gamblers were betting that he would prove to be the better shooter in the contest, though well-known Fauci family mobster Big Tony was taking the other side of those bets. Tyson was set to play in a player development league for a year after eschewing the fake vaccine card offered by doctors working with numerous top college programs. Tyson was the top high school scorer and rebounder in California, and in the top three in assists, steals, and blocked shots. His 98% free throw percentage was a national record. While Tyson did not play for a big name high school program, and had little promotion behind him, scouts chattered among themselves that he was among the most versatile young shooters in history. The million dollars would have been life changing for his impoverished family.

The two basketball stars were destined to put on a show. It seemed that the whole world was tuning in. Chinese fans started to take an interest. The President of the United States found out about Tyson's talents and said that he would be, "maybe a game changer at the professional level. Maybe. Maybe not." The media began to refer to Tyson as the "president's pet shooter", calling his potential as a draft pick one-dimensional and dangerous to his team. Vegas started to see more bets on Pharmangton surge.

Big Tony reportedly locked in some profits before the main event.

An Anticlimactic Contest

The plan was to allow each shooter to take 3-point shots until they made 100 total 3-pointers, over 10 rounds of 10 shots each.

After the third round, both shooters were lighting it up, though Brian led with an incredible 30 shots made out of 34 attempts to Pfred's 30 shots made out of 40 shots taken.

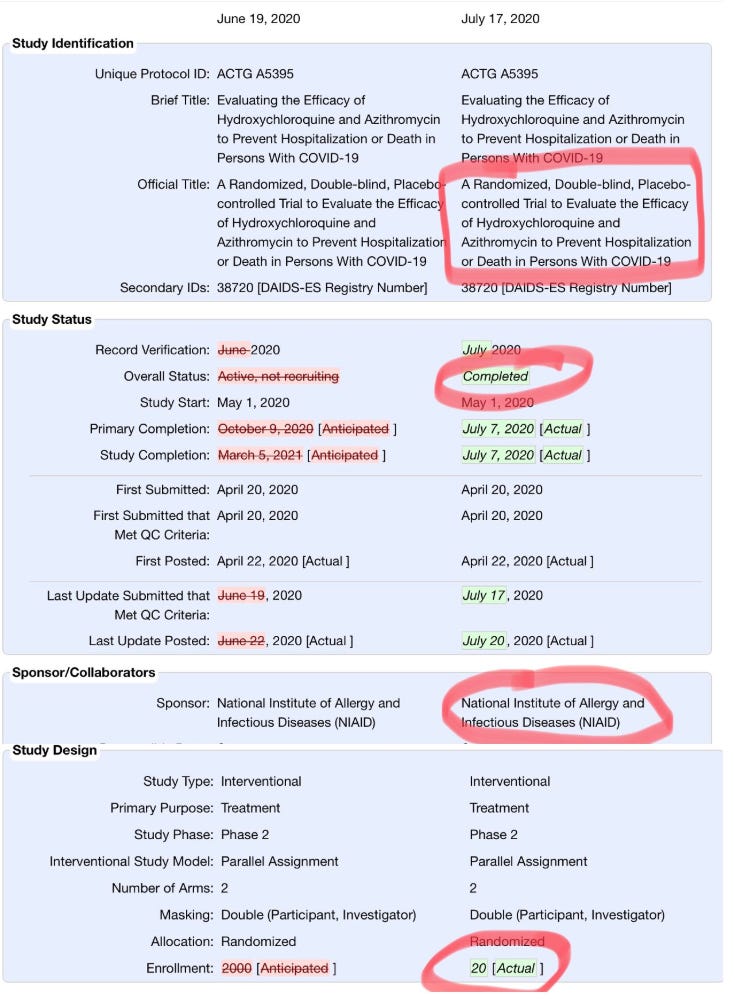

During a pause before the fourth round of shooting, the lights in the arena went out for half an hour. After the lights were turned back on, the contest's head official, appointed by a committee that included a business run by Pfred's extended family members just hours before the event began and announced while the POTUS was speaking on the jumbotron, David Boulware, declared the contest to be over, stating that there was no point in continuing. Further, Boulware declared, statisticians who work with Boulware computed a p-value greater than 0.05 when comparing Tyson's and Pharmangton's misses.

To add insult to injury, Boulware stated that since Tyson did not win the million dollar prize that he never could beat Pharmangton, so there was no point in finishing the competition now or in the future.

Confusion swept through the crowd, though many had read newspaper reports that quoted Boulware suggesting that there were "red flags" in Tyson's past practice performances. Some of them accepted the official ruling immediately because, well, it was official. Others accepted it because they were rooting against the president's pick. A few of them shouted in the faces of fans wearing Tyson jerseys as they exited the stadium, and even told them things like, "Where's your miracle shooter now?" and "You're the reason we can't have nice things!"

Some basketball coaches from various levels of play approached the contest officials to discuss the controversial outcome or outright advocate for Tyson. Several of those coaches received phone calls from their employers during that conversation and were told that they were fired. One was sued for not immediately taking off his coach's lapel.

Coach Raoult, the winningest coach in the history of the NBA chimed in, saying he taught both shooters during training camps, and that Tyson always beats Pharmangton. Coach Raoult was a forced to be reckoned with having invented more basketball plays and training techniques than anyone in the history of the sport. His players were always winning 3-point contests, it seemed.

Coach Raoult fans in the crowd started chanting his name, but court officials had security throw them out and blamed him for ruining the atmosphere. One official whispered to Raoult that he too could be an official, but he refused to respond. After that, a coach waved the media over and told a story about how one of Coach Raoult's former players cheated on a drug test in order to not be suspended from playing for Coach Raoult, and that he must have known. Meanwhile, a member of the press got one of former players on the phone declaring the coach to be a real "ball-buster". One of the cheerleaders called Coach Raoult a "cult leader" while an assistant coach wearing a lot of bling for an assistant coach threatened Raoult's life. Some really crazy rumors got passed around. The NBA then announced that it no longer counted stats more than a decade old when deciding who the winningest coaches are, so Coach Raoult is now just kind of average since he semi-retired to a general manager position a few seasons back.

Meanwhile, NBA coaches giving interviews with the press each repeated the talking point, "Nobody has proven to beat Pharmangton in an official 3-point shooting contest."

Some coaches filed formal complaints, and were answered by a coach of a girl's field hockey team who had never seen a basketball, but was certain that he could coach professionally. The NBA immediately began a "greatest coach who never got the chance" campaign on his behalf.

While all this was going on, television commentators repeated to those watching at home that "Tyson proved to be unable to defeat Pharmangton in a head-to-head matchup." Over and over and over and over again.

While all this was going on, Tyson and Pharmangton were playing games of H.O.R.S.E in the parking lot. Tyson won most all of them. Only a handful of dedicated fans watched the free show. Upon hearing about the consistent results, officials declared all those results were meaningless if they weren't adjudicating.

The Wisdom of the Spectator Crowd

While most fans were leaving the stadium, a few curious ones went onto the court and began investigating court conditions. One of them noticed that the basketball rims were different on the two sides of the court. The rim that Phramangton shot at was made with a softer material. Nobody knew what to make of that, though there was speculation that this could dampen impact from a basketball, keeping a few close shots from bouncing out. Officials had failed to mention the different rims prior to the competition.

Just when Tyson advocates began to look sympathetic, officials announced that they'd caught a man selling illegal Tyson jerseys just outside the stadium.

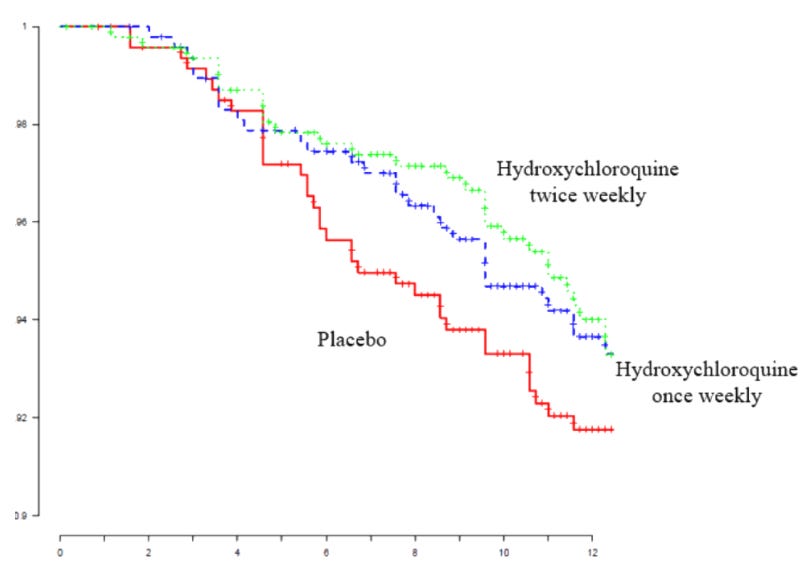

While debate raged on, and fans who still waited around to see if Tyson would win the prize were told to leave or be banned from sports arenas, several sports statisticians pleaded their case. One of them pointed out that computing a p-value prior to the scheduled end of the contest seemed like a motivated decision, and not a good look for an official tied both to the contest funder and also one of the players. Another re-evaluated the performances of the athletes based on clock time, saying that the consistency of Tyson's lower time between made shots was statistically significant (meaning p < 0.05). Another pointed out that measuring Tyson's performance in every way (not just misses) was the better way to decide the winner, and that Tyson won. One pointed out that Tyson's 3-point shooting percentage in real games was far better than Pharmangton's, but was quickly told that "high school is over, loser." One wise man among them pointed out that the officials counted the statistics improperly, and that the p-value was less than 0.05 now matter how you look at things.

One statistician spoke up and said, "Look, fellas, one way or another, this idea that Tyson cannot beat Pharmangton is completely absurd. It's bat-CoV insane. Tyson was beating him. Spanking him, really. And that was with a fake rim, during Pharmangton's best day, and on Pharmangton's home court. He just did not have enough time to finish the job. He did not "fail" at anything. These two players are scheduled for a few other 3-point contests at exhibitions, soon. Why don't we hold off on this 'Tyson failed' nonsense and see what the p-values look like at these other contests?"

Officials looked nervous. This was the head of the Administrator of the Ultimate Intergalactic Arbitration Council of Statistics and All Other Matters speaking. But it was true that other contests were planned. If Tyson were to defeat Pharmangton soundly at any one of them, they'd look foolish for having dubbed him a proven failure. And there was a lot of money at stake.

What Happened Next

A week later, at the same arena, fake rims still on Pharmangton's end of the court, Tyson was once again leading Pharmangton by a solid margin when the contest was once again stopped ahead of schedule. In a scene similar to the earlier one, Boulware declared that Tyson proved unable to defeat Pharmangton.

The next contest, which was sponsored by Big Tony's sports betting operation in Las Vegas, was canceled while Tyson was riding his bicycle several hundred miles from home after his car broke down. The excuse given was fans on both sides had become rabid and violent toward one another, so nobody wanted to show up to the venue. Tyson's fans blamed the NBA for turning the contests into volatile partisanship. NBA officials fired back at critics, blaming politicization of Tyson's career on them, suggesting that all statistics collected during his practices and non-NBA games were not good evidence.

Another contest was held with Boulware officiating, fake rims still favoring Pharmington. After a few shots, Tyson took the lead and never looked back. Still, he was declared a failure because there were not enough shots taken for the result to be "statistically significant".

Some fans pointed out that Tyson schooled Pharmington over and over in similar contests in India, but officials deemed India a "shit-hole basketball nation", insisting that only American basketball authorities understood how to do basketball the right way.

Months later, the HERO Contest was held at Duke University, the epicenter of college hoops for three decades. With Tyson in the lead once again, the contest was halted early. As usual, Tyson's detractors declared that he had failed once again.

Exasperated after months of unnecessary drama, Tyson broke down and cried talking with an audience back home.

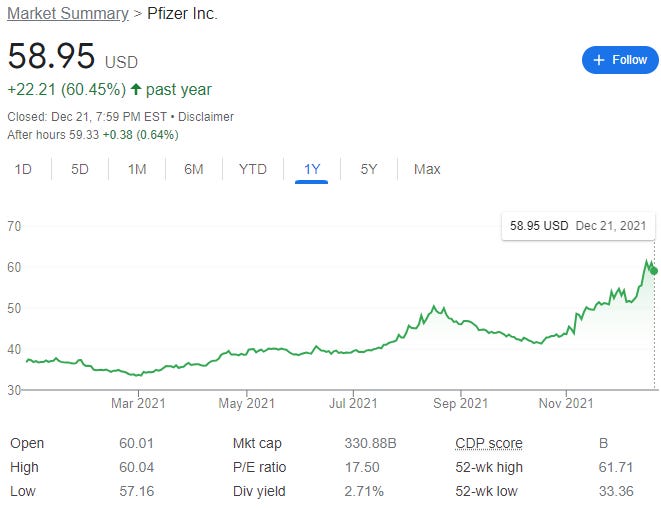

While contests were repeatedly scheduled and uncompleted, and the NBA declared Tyson, who rarely even trailed Pharmangton but for scarce moments in dozens of shooting competitions, a "washed up failure", they were busy running ads declaring, "We await Pharmangton!"

A Statistician's Take

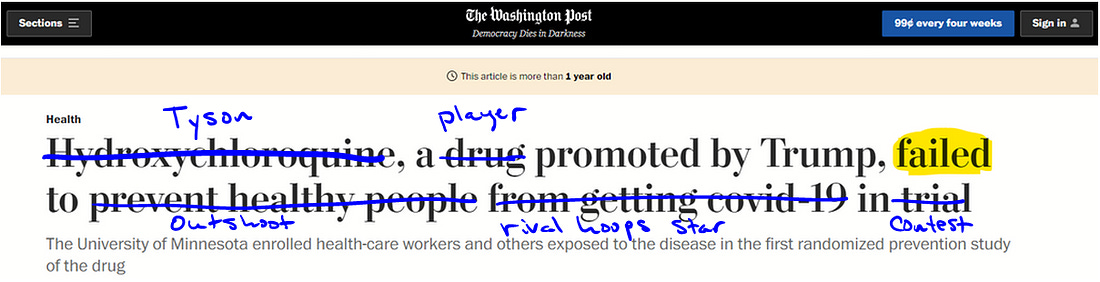

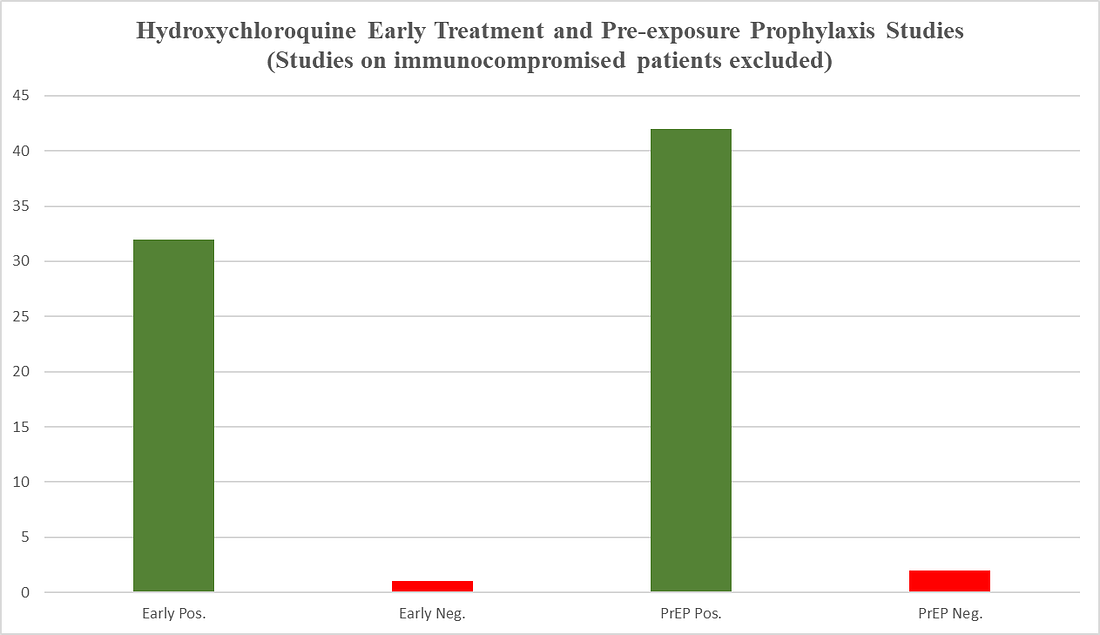

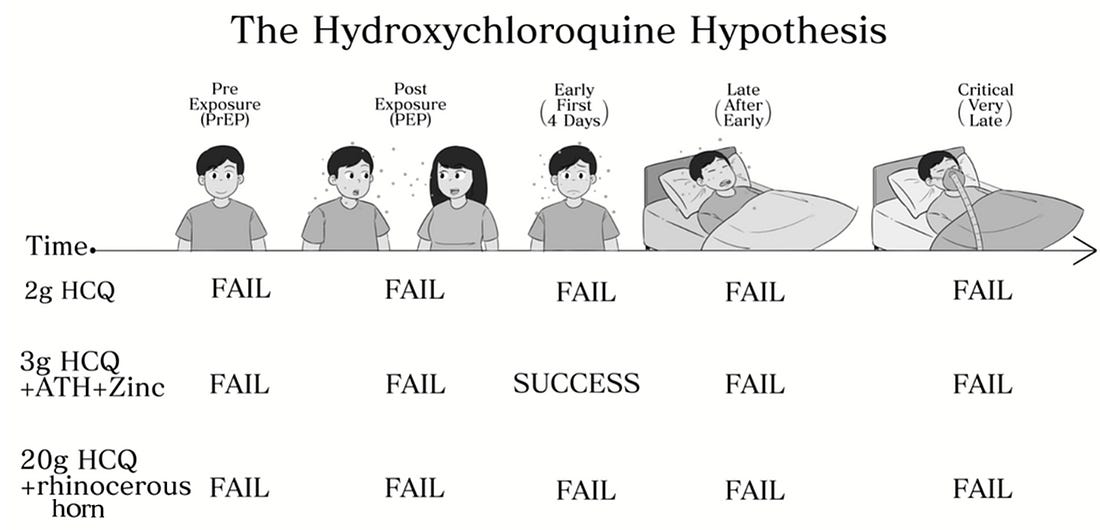

Hopefully you caught on to the hefty pile of absurdities in this tale, which is the thinly disguised tale of how hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) was deemed to have "failed" in randomized control trials. But I'd like to take a moment and walk through, as simply as possible, how an honest statistician sees the evidence.

No one trial can possibly "demonstrate failure" of a drug. If one protocol works, the drug is a success. The logic is quite simple: a drug can fail in infinitely many ways and still be a good drug. Maybe even a top notch drug. And, in fact, all drugs fail in infinitely many protocols. The FDA approves drugs every year that did not reach statistical significance in early small trials.

Not reaching "statistical significance" is not considered "failure" by any statistician. The value of evidence is, and always should be, in the eye of the beholder who should be willing to relate it to all other evidence as best as possible. When trials are not well enough powered to achieve convincing results, we can consider their context in terms of a larger body of evidence. Outside of biopharmaceutical research (and areas of "science" that are barely science), the larger statistics community rolls its eyes at the notion of some bright line passed down by the gods of chance that is equal to 0.05 upon first computation of a p-value which is itself not what pharmastatisticians like to sell it as:

Although statistically the null hypothesis does not necessarily relate to no effect or to no association, the presumption that it does relate to no effect or association frequently is made in medical research and the one we will consider here. The introduction of these theories in scientific reasoning has provided important quantitative tools for researchers to plan studies, report findings, compare results, and even make decisions. However, there is increasing concern that these tools are not properly used [9, 10, 13, 20].

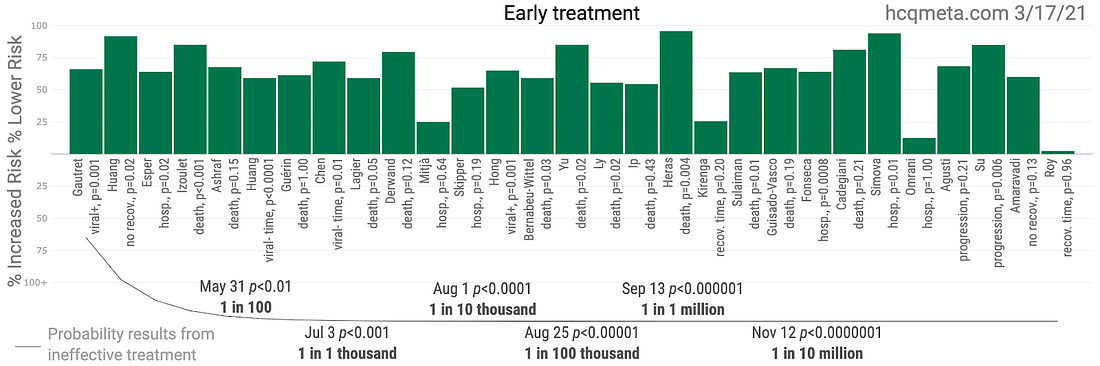

The concept of "proof" is a logic/mathematics concept. It has no place in science or inferential statistics, except perhaps in the use of inequalities that imply computational boundaries of outcomes. When somebody like Big Tony Fauci says, "I need proof", you should know he's a conman. On the other hand, if a body of evidence like this doesn't convince you that "there might be something to this", you might not have a brain. Repetition and consistency are hallmarks of convincing statistical evidence.

Anyone telling you that HCQ “failed” in clinical trials does not understand statistics on a basic level or else they understand them well enough to craft a lie.

Comments

Post a Comment