Tomorrowland Has Fallen!

Tomorrowland Has Fallen!

Has anyone else noticed just how odd it is that so many people on the progressive end of our cultural landscape are frantically trying to convince everyone that the Omicron variant, the latest mutation of the Covid-19 cold virus, really is the end of the world? I freely grant that a lot of people are ill just now—that’s what usually happens in the temperate zone’s winter, you know, when the latest respiratory viruses make their rounds. I grant just as freely that hospitals are scrambling to keep up—many of them have laid off up to half their staff as a result of vaccine mandates, after all, and they’re being besieged by mobs of people who have been convinced by the media that ordinary cold symptoms mean they’re about to die.

The result is a collective frenzy being eagerly fed by a great many people. Of course it’s not surprising that the corporate media would push scare stories at full volume. Whoring out the news to sell advertising space is their stock in trade, and “if it bleeds, it leads” has taken precedence over responsible journalism since before there was responsible journalism. Still, this isn’t limited to the media. A great many people seem remarkably eager to insist that the pandemic can’t be winding down. In that eagerness I sense the approach of convulsive change.

Granted, a case can be made that there are practical if unmentionable reasons for this habit of sedulously cultivated panic. To begin with, as Freddie deBoer has pointed out in a trenchant post, being terrified of the Covid virus has become a venue for status competition among members of the privileged classes. It’s an old story, at least as old as that fine fairy tale “The Princess and the Pea.” Just as the princess in the story showed her royal status by being so hypersensitive that she could feel a single dry pea under seven mattresses, our current princesses—and princes, to be sure—display their status by insisting that they can contract a virus through seven face masks.

Another reason to cling to the pandemic is a phenomenon I’ve discussed in previous posts. One of the unintended side effects of shutting down the economy in 2020 is that a great many people found themselves with ample time and solitude to reflect on their lives, and realized that their jobs are so miserably paid, and made so intolerable by the humiliating petty tyranny that passes for management in today’s America, that it simply wasn’t worth going back to work. A significant share of the US working classes responded to this reality by finding other ways to support themselves, with impacts that are still ricocheting through the global economy.

The privileged classes have also seen a wave of resignations as a result of that gift of reflection, but that had another dimension as well. One of the ways America’s caste system played into the pandemic was that most people in the privileged classes got to work from home, instead of being laid off or made to go into work straight through the crisis the way the working classes did. That showed a good many people in the managerial class that they can do their jobs perfectly well without the poisonous office politics and mean-spirited authoritarianism of their workplaces. Now that the pandemic is winding down, they’re scrambling around for excuses to stay out of the office a little longer. The latest Covid variant is just another source of grist for that mill.

These are potent forces, but I don’t think they explain the intensity of the terror, or the way that it’s detached itself from mere biological realities over the last two years. Watch the way that the people who are shrieking about the Omicron variant fixate on case numbers and go out of their way to avoid talking about how few people have been killed or made seriously ill by it. Watch the way that these same people pounce, with something that looks unsettlingly like delight, on any suggestion that some other microbe is about to spring out of hiding and kill us all.

For that matter, the overreaction to the Covid-19 phenomenon is really rather odd, when you think about it. If you subtract all the people who died with rather than of Covid-19 from the statistics, it’s pretty clear that what we’ve dealt with is an ordinary respiratory epidemic like the 1958 and 1967 influenza outbreaks. Those had comparable fatality rates, and were dealt with by throwing the available resources into protecting the old and vulnerable—not by shutting down whole economies, shredding civil rights, and shoving inadequately tested experimental drugs on entire populations. What we’ve seen over the last two years doesn’t look like a constructive response to a pandemic. It looks like the desperate gyrations of control freaks who are trying to avoid dealing with their fears by piling exorbitant demands on everyone around them.

Thus I’d like to suggest that something of the sort may be involved in the love affair between the managerial aristocracy and the Covid-19 virus. I think that it’s a displacement activity.

If you know much about ethology—the study of animal behavior—you already know all about displacement activities. For those who don’t have that background, I’ll summarize. Most social species have ways to deal with aggression short of killing each other. Watch two starlings who are upset at each other. They may suddenly start preening their feathers, or draw themselves up as though about to fight, or even peck suddenly and violently at some object besides each other. Human beings do the same thing: watch an angry man scratch his head in frustration, ball up his fists on his hips, or slam a fist down on a table, rather than punch the daylights out of the person who’s angered him. Those are displacement activities.

Anger isn’t the only emotion that generates displacement activities in animals, or for that matter in humans. One of the more interesting details of human collective psychology is the way that fear can drive even more elaborate displacement routines, especially when there’s nothing that can be done about the actual reason for the fear. Consider the witch hunts that followed in the wake of the Black Death. For three and a half centuries after bubonic plague first swept through Europe, new outbreaks of the disease were a constant threat, and the medical knowledge of the time offered no effective means of prevention or cure.

The result? Panic over evil witches became the displacement activity du jour, and around fifty thousand people were burnt or hanged as a result. (No, it wasn’t nine million, nor were they all women; the Neopagan movement, back in its heyday, competed heavily in the Oppression Olympics, with the usual collateral damage to mere historical fact.) People couldn’t do anything about the plague, but they could burn witches, and so they did. As soon as the bacterial ecology of Europe changed and Yersinia pestis, the plague bacillus, died out there, the witch hunts promptly ground to a halt.

That was an extreme example, but then the Black Death was an extreme situation. Y. pestis wiped out a third of the population of Europe in four short years during its first outbreak, then came back a decade or so later and took another ten percent. Outbreaks followed every decade or two thereafter until the pandemic finally burned itself out in the late seventeenth century. Staying sane in a situation like that takes a herculean effort, and not many people managed it. Our current situation is much less drastic, and it has a curious feature: the displacement activities we’re seeing this time around are almost entirely restricted to the comfortable classes. Visit your nearest high-end grocery store, for example, and everybody’s masked up; visit a dollar store in the down-at-heels part of town, and nobody worries about masks at all.

That last point is the clue that makes sense of the whole puzzling phenomenon. Here in the United States, the professional and managerial classes have dominated industrial society for around ninety years now, since they replaced the capitalist classes at the top of the pyramid of power in the wake of the Great Depression. That’s a good long run for a ruling caste. The capitalist class they replaced seized power across the northern half of the country in the 1830s and then took over the national role of a previous elite, the plantation aristocracy, in the Civil War of 1861-1865. The plantation aristocracy had a longer time on top, but agrarian feudalism is a more durable system than either industrial capitalism or managerial corporatism.

The reason these latter two systems are short-lived, in turn, is that they’re predicated on change, while agrarian feudalism is predicated on stability. The industrial and managerial revolutions were both driven by the rise of a brash, energetic, impatient social class that wanted power and didn’t care what it had to break to get it. Such classes take over when society has piled up a big backlog of unsolved problems, and retain power by solving some of those problems. If they could stop there, they’d be fine, but of course they can’t. Committed to change, and to specific kinds of change at that, they zoom straight past the point of diminishing returns and then the point of negative returns, until the policies that solved the old problems become the main source of new problems. The elite classes can’t solve those because the policies in question have become central to their collective identity, and so in due time, down they go.

If you want a useful perspective on the twilight years of a ruling class that’s locked itself into this trap, early twentieth century literature is a fine place to start. In the waning years of industrial capitalism, the accelerating failures of the system were impossible to ignore but nobody in the comfortable classes could let themselves think of a way out of them. That’s where you get the novels of Edith Wharton and Henry James, brilliant portrayals of the lives of the privileged as they circle the drain. It took the Great Depression and a disastrous loss of prestige on the part of the capitalist class to fling open the door to novels such as Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge, where the protagonist finishes the tale by doing the unthinkable, letting himself drop out of the comfortable classes, and doing something useful with his life.

For me, at least, it’s hard to read any of the literature of those years without getting a potent sense of déjà vu. The same autumnal sense of an era past its pull date, the same spectacle of people and institutions going through motions that stopped functioning a long time ago, the same plaintive voices wondering why the world just doesn’t seem to make sense any more—it’s all present and accounted for, the familiar backdrop for the last few decades of public life in the United States and a good many other industrialized nations. The sole remaining questions are what combination of crises will topple the hapless ruling class from its position, and how soon that inevitable moment will arrive.

Yet admitting that the managerial class has turned out to be incompetent at running societies is unthinkable, to members of that class. It’s not just a matter of status panic, either. The entire collective identity of our managerial aristocracy is founded on the idea that they’re the experts, the smart kids, the people who really know what’s what. They justify their grip on the levels of collective power by insisting that they and they alone can lead the world to a sparkly new future. That’s the theme of the slogans under which they seized power, and it remains the core of their ideology and their identity: “We can make the world better!”

Central to that slogan and the hubris that unfolded from it was the twentieth century’s supreme delusion, the belief that history is a straight line leading in a single direction that can be known in advance. The mythology of progress I’ve critiqued at length in a variety of venues is only one form that this delusion took; you can find it equally often in spirituality, spanning the notional space from Rudolf Steiner at the century’s beginning to Ken Wilber at its end. Martin Luther King’s much-quoted claim that “the arc of history bends toward justice,” for that matter, was fine rhetoric but bad scholarship, since history isn’t an arc and doesn’t bend toward any destination. Rather, it’s a landscape across which various groups of people wander in assorted directions, and generally end up not far from where they began.

That, in turn, defined the destiny of the managerial aristocracy. They strode boldly off toward Utopia, only to find that it wasn’t where they thought it was. The results of that quest are being counted out today in the coinage of total failure. From the economy to Afghanistan, from education to (ahem) public health, if you compare the statements of qualified experts to the facts on the ground, the experts generally end up looking like idiots. It doesn’t help that members of the managerial class are inevitably sheltered from the consequences of their mistakes, no matter how disastrously wrong those are or how many people get hurt as a result. That’s why nowadays, when experts make a claim, a very large number of people take the opposite view on principle. Worse still, those who do this and ignore the experts very often turn out to be right.

For the last six years now, accordingly, the failures of the managerial class have become a massive political issue across much of the industrial world. Britain’s Brexit referendum and the 2016 US presidential election both marked important turning points in that process, as significant numbers of ordinary people decided that the experts didn’t know what they were talking about and refused to vote as they were told. The various tantrums thrown by pundits, politicians, and self-anointed influencers since that time haven’t accomplished much, aside from convincing even more people to ignore the increasingly shrill demands of a failing elite.

That’s sending waves of stark shuddering terror through the managerial aristocracy. If the deplorable masses stop bending the knee and tugging their forelocks whenever one of their self-proclaimed betters mouths a platitude, after all, how long will the authority of the managers last? That terror, in turn, gives rise to the displacement activities discussed above. Since it’s impossible for them to admit to themselves that they’ve failed, much less that everyone else is aware that they’ve failed, they find other things on which they can focus their feelings of panic. The Covid virus is one of those. It wasn’t the first and it doubtless won’t be the last, but it’s serving its purpose now, which is to allow members of the managerial class and its hangers-on in the media and the academy to distract themselves from the end of their era of power.

The shockwaves of social transformation that are unfolding as the managerial age winds up will give us plenty to discuss in the years ahead. One thing I’d like to discuss here is the impact those changes will have on the future. For the last century, the only future most people seemed able to imagine was the future the managerial class liked to portray—a world of titanic technologies, gargantuan bureaucracies, stark and sterile environments, and an endless parade of experts bringing on changes over which ordinary people had no say at all. “Science Explores, Technology Executes, Mankind Conforms”—the motto of the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair—was for all practical purposes the battle cry of the managerial aristocracy.

That was one side of the narrative, of course. The other side was the horrible apocalyptic doom that was sure to swallow us all if we didn’t let the experts do whatever they wanted. That was a constant dirge in the mouths of the managerial class, endlessly varied in detail, never changing in its basic theme. As the era proceeded and life for people outside the comfortable classes became steadily more miserable, in turn, that horrible apocalyptic doom started losing its capacity to frighten. The same thoughts that inspired a quarter of the US workforce to quit their jobs last year led a smaller but still considerable number of people to decide that if the only thing they had to look forward to was the wretchedly antihuman future marketed by the managerial class, some kind of horrible apocalyptic doom started having a certain noticeable appeal.

You can measure just how bleak the Tomorrowlands brandished by the managerial class have become by watching how enthusiastically the corporate media and its tame pundits rewrite the past to make it look as bad as possible. Plenty of rhetoric has been deployed around the much-ballyhooed 1619 Project, for example, but most of it’s missed the central theme of that orgy of frantic cherrypicking and historical malpractice. The 1691 Project can best be described as a grand effort to make the American past look bad, so the present looks a little less wretched by comparison. The mere fact that so much effort had to be expended in that attempt shows just how utterly the managerial class has failed. May I state the obvious? This is not the behavior of a ruling class in control of its own destiny.

The point I want to stress here is that the grim Brutalist future to which people were expected to conform was never more than a mirage, and attempts to revive it in new forms—I’m thinking here especially of the Stalinist absurdity of Klaus Schwab’s “Great Reset”—carry all the conviction of the proverbial three-dollar bill. It’s not just that the resources needed to prop up that sort of system no longer exist, though of course that’s true, or that a good many of the core technologies that would be needed to make it function either don’t work or aren’t cost-effective enough to bother with, though this is also true.

Even more important is the fact that the social consensus needed to make it happen doesn’t exist. Nor can that consensus be manufactured, because too many people nowadays assume as a matter of course—and for very good reason—that the experts are wrong, and the consensus they’re trying to push on the rest of us is yet another round of cerebral flatulence that won’t work. As a matter of practical experience, goverments do in fact exist by the consent of the governed, and so do ruling classes; that consent is cracking around us as I write these words.

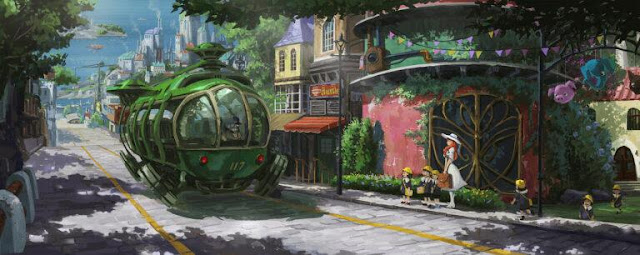

That opens up a landscape of possibilities very few people have begun to explore yet. The futures open to us, it turns out, aren’t limited to a regimented bureaucratic Tomorrowland on the one hand, and a smoldering postapocalyptic wasteland on the other. What if it turns out that the landscape of 2200, say, looks more like this?

The painting’s titled Arrival and it’s by Charles Lee; you can find more of his work here. Nothing in that image would be impossible in a world coping with sharp limits on energy and nonrenewable resources. A future society powered by biofuels and renewable energy sources won’t have the kind of gaudily extravagant technologies we’re used to, but it could very likely support cities with some form of public transit, not to mention streets, schools, comfortable buildings, and an aesthetic closer to Art Nouveau than to the crazed pursuit of ugliness for its own sake that dominates today’s built environments.

History shows us that a society need not have jetliners, server farms, skyscrapers, or spacecraft to provide its citizens with food, shelter, clothing, sanitation, education, and intellectual and cultural activities. (We’ve already seen that a society can be fully stocked with the jetliners et al. and still be miserably incompetent at providing these latter good things.) As the managerial aristocracy completes its fall from power and its dreary plastic daydream of Tomorrowland falls with it, we enter a space of possibility in which a much wider range of choices come within reach. With this in mind, I’ll be revisiting some earlier themes of my blogging in the months ahead, and sketching out some of the possibilities I see before us.

Tomorrowland has fallen. Off beyond its smoking ruins, there are better things waiting. Will you join me in the journey there?

Comments

Post a Comment