Remembering Marshall McLuhan

Remembering Marshall McLuhan

The Oracle of Mass Media

It is impossible to undertake the study of mass media without considering the indelible influence of Marshall McLuhan (1911-80). McLuhan, who practically invented this discipline, had an uncanny gift for coining a catchy term (“global village”) or phrase (“the medium is the message”) that is well-known even to those who have never bothered to read his still-relevant works. Without his relentless determination to understand the subtle effects of the media on human consciousness and society, our understanding of these omnipresent technologies would be severely limited.

Despite his enormous influence on the field of mass communication, McLuhan opposed the technological changes that swept the 20th century, as he remarked in a 1966 interview:

I am resolutely opposed to all innovation, all change, but I am determined to understand what’s happening. Because I don’t choose just to sit and let the juggernaut roll over me. Many people seem to think that if you talk about something recent, you’re in favor of it. The exact opposite is true in my case. Anything I talk about is almost certainly something I’m resolutely against. And it seems to me the best way to oppose it is to understand it. And then you know where to turn off the buttons.

Although McLuhan’s opposition to technological innovation emanates from a discernible conservative tradition, the relation between his studies of mass media and his political biases has not always been well understood. When he became a media celebrity in the 1960s, his dispensation of advice to various corporations—including IBM, General Motors, and AT&T—convinced most observers on the left that he was a lackey for corporate capitalism. In the same decade, his apocalyptic predictions of social upheaval induced by electronic media persuaded many on the right that he was a fan of the counterculture. And in the 1970s, when McLuhan was active in the pro-life movement and a critic of Vatican II, those stances were rarely connected to his study of media at all. Famous admirers such as Pierre Trudeau and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. concluded that there was nothing essentially political about McLuhan’s ideas. Given this wide disagreement, is it possible to see any substantial cohesion between McLuhan’s conservative politics and his study of the media?

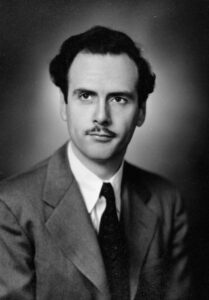

Herbert Marshall McLuhan was born in Edmonton, Alberta on July 21, 1911, the son of an actress and a real-estate and insurance salesman. Having spent his formative years in western Canada, young McLuhan was exposed to a growing movement of agrarian protest against the eastern railroad barons and bankers who sought to control the destinies of yeoman farmers scattered across the prairie hinterland. Later in life, in a Maclean’s article, he reflected on how the centralization of economic and political power in eastern Canada at the expense of other regions had not changed one whit:

What is Canada? The Prairies regard Toronto as enemy territory and so do Quebec and the Maritimes. All the decisions are made there on everything, and their miseries are invented there—that, plus the

opulent and rather self-pretentious image that Ontario political and business figures present to the westerner. They look like something out of a Mac Sennett comedy. I personally can’t take them seriously either.

After a youthful flirtation with Italian fascism, McLuhan gravitated toward the ideas of prominent Catholic traditionalists such as G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, authors who shared his misgivings about capitalist democracy. When he left Canada in 1934 to eventually pursue a Ph.D. at Cambridge University, his interest in the “Chesterbelloc” camp deepened. He later joined the Distributist League, which called for an economic system whereby the owners of small firms and farms would sell their goods directly, primarily in local markets, all without interference from large corporations and the centralized state.

In his first scholarly publication, “G. K. Chesterton: A Practical Mystic” (1936), McLuhan lavished praise on his subject for demolishing the dogmas of progressivism and economic determinism:

Mr. Chesterton has exposed the Christless cynicism of the supposedly iron laws of economics and has shown that history is a road that must often be reconsidered and even retraced. For, if Progress implies a goal, it does not imply that all roads lead to it inevitably. And today, when the goal of Progress is no longer clear, the word is simply an excuse for procrastination.

In his dissertation on the Elizabethan satirist Thomas Nashe, McLuhan makes clear that he saw nothing “progressive” in the modernist account of history, one that celebrated a “Christless cynicism.” In his work on Nashe, McLuhan also took aim at Machiavelli and the Reformation for effecting a “violent scission of nature and grace,” a fateful weakening of the medieval teleology of nature. With nature’s moral authority out of the way, Machiavelli’s “ideal prince” was free to impress “his character upon the flux of events” and live solely for the pursuit of power unrestrained by either nature or grace. Unsurprisingly, McLuhan also began to study the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas at this time.

However, the unmistakably Catholic flavor of McLuhan’s early writings, coupled with his conversion to Catholicism in 1937, does not fully explain his deep sympathy for right-leaning social critics, many of whom were not Catholic. Around this time, he became enamored with the literature and culture of the American South. In 1939, McLuhan married the Texan Corinne Lewis while teaching at St. Louis University in Missouri. There McLuhan came to appreciate the “Fugitive Group” of Southern writers, including Donald Davidson, Allen Tate, and John Crowe Ransom. In his 1947 essay “The Southern Quality,” McLuhan credited this Southern agrarian tradition with an admirable “aristocratic” sense of “personal responsibility to other human beings for education and material welfare,” a sense of duty that was utterly absent within Northern capitalism. “A Carnegie or a Ford, like a bureaucracy, molds the lives of millions without taking any responsibility,” he wrote.

During a teaching stint at Assumption College in Windsor, Ontario, in the mid-1940s, McLuhan struck up a friendship with the noted Vorticist painter and cultural critic Wyndham Lewis. In his 1944 essay “Wyndham Lewis: Lemuel in Lilliput,” McLuhan shared Lewis’s lament over the capitalist destruction of the traditional family. “The dynamic logic of a cheap labour market naturally leads to an attack on the family.” The entry of women into this market forces down “men’s wages to the point where home-making, housekeeping, and child-rearing is a luxury reserved for a small class.”

(Josephine Smith / Library

and Archives Canada)

In 1946, McLuhan secured a professorship in English literature at St. Michael’s College, a Roman Catholic institution affiliated with the University of Toronto. This was McLuhan’s academic home until his death in 1980. In 1951, he published his first book, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. This work is a critique of the effects of mass advertising on culture, society, and mores. It is also a book with a very unconventional structure, consisting of short essays on various ads and images taken from magazines, comics, and newspapers.

Despite his often humorous style, McLuhan’s purpose was deadly serious. The phrase “the mechanical bride” functioned as a metaphor that zeroed in on how advertising reduced even the most precious human experiences—sex included—to problems “in mechanics and hygiene.” The whole point of advertising was “to keep everybody in the helpless state engendered by prolonged mental rutting.” Even powerful persons such as executives, politicians, and movie stars were “puppets only vaguely aware of the strings controlling their movements.” With a nod to Edgar Allan Poe’s “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” McLuhan advised his readers to approach advertising in the same way that Poe’s sailor saved himself: “by studying the action of the whirlpool and by co-operating with it.”

Almost 20 years after the publication of The Mechanical Bride, McLuhan appeared to disavow this study as “extremely moralistic” and “sterile and useless,” given the fact that he had focused on media—comics, newspapers, and magazines—that were becoming obsolete with the rise of television. Many of his critics on the left chided McLuhan for this apparent repudiation of his first foray into media studies, accusing him of losing interest in the way that capitalist media function within modern democracies. Yet it is possible to spy considerable continuity between The Mechanical Bride and his more popular books that appeared during his heyday in the 1960s. Although McLuhan tried to convey a far less judgmental stance in these works, his original contention held firm: that human beings simply did not understand new media.

In The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1962), McLuhan presented a theory of history that highlighted the prominence of different media. Building on the ideas of Canadian economic historian Harold Innis, McLuhan began with the oral (or tribal) age, during which the speaking and singing of words—characteristic of ancient tribalist cultures—were the dominant modes of communication. Next was the writing (or literacy) age, in which pictographs and then the alphabet held sway. With Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the 15th century came the print age. Mass literacy, which later spawned nationalism and capitalism, became an actuality for the first time in history. Finally, the invention of the telegraph in 19th century heralded the electronic age, which continues to this day.

Amidst these revolutionary changes, is there anything that has remained the same? According to McLuhan, human beings throughout history have consistently failed to understand the effects of technological change until it was too late, a phenomenon that he called “rearview mirror” thinking. In Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), McLuhan’s main thesis—that media extended the sense organs (e.g., the telephone extended the ear)—is simple enough to understand. But he also insisted that the various effects of new media were not usually intelligible, even to their creators. Far too often, the users of media ignore the relation between “figure” and “ground.” Although the medium may be the figure (the object of attention), the ground (the sociohistorical environment) that the medium shapes is often invisible.

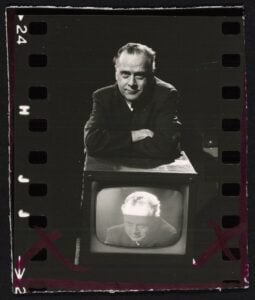

January 1967 (Bernard Gotfryd

/ U.S. Library of Congress)

McLuhan’s famous distinction between “hot” and “cool” media is relevant here. Radio is a hot, or high-definition, medium because it provides a great deal of information and content, leaving its listeners in a passive state. By contrast, TV is a cool, or low-definition, medium because it provides little information or content, leaving the audience to fill in the gaps. Referencing the first Kennedy-Nixon debate of 1960, McLuhan was not surprised that those who listened to the debate on the radio thought Nixon was the winner, whereas those who watched it on TV thought Kennedy had won. “TV is a medium that rejects the sharp personality and favors the presentation of processes rather than of products.” Nixon’s hot or classifiable personality was ill-suited for the cool medium of TV. The fact that Nixon provided the most thoughtful content did not matter on a medium that rewarded low content as well as a charismatic image such as JFK’s. The message of each candidate was subordinate to the medium. Put differently, the medium was the message.

McLuhan detected another pattern in human history. The tribalism that coincided with the oral age had never quite disappeared. In brief, tribal referred to places where the oral tradition, decentralization, and cultural diversity were predominant. Those aspects returned with a vengeance during the electronic age, which had rendered print media and literacy nearly obsolete. In the process, electronic media also created a “global village” of interconnected peoples that could learn about each other through the magic of instantaneous communication. The preoccupation of spying on all the members of that global village was not far behind. As McLuhan once said to Maclean’s Editor in Chief Peter Newman, “The new human occupation of the electronic age has become surveillance, CIA-style. Espionage is now the total human activity.”

In an interview with Playboy in 1969, McLuhan predicted the breakup or “Balkanization” of the United States:

“The U.S., which was the first nation in history to begin its national existence as a centralized and literate political entity, will now play the historical film backward, reeling into a multiplicity of decentralized Negro states, Indian states, regional states, linguistic and ethnic states, etc.”

Suffice it to say, the new tribalism had its dangers. Although McLuhan, as a faithful Catholic, hoped that a greater global harmony might arise from it, the evidence persuaded him that conflict was far more likely. The uneasy conformity of the print age would yield to the breakdown of consensus during the electronic age. In an interview with Playboy in 1969, McLuhan predicted the breakup or “Balkanization” of the United States:

The U.S., which was the first nation in history to begin its national existence as a centralized and literate political entity, will now play the historical film backward, reeling into a multiplicity of decentralized Negro states, Indian states, regional states, linguistic and ethnic states, etc.

Meanwhile, post-literate youth “mindlessly acts out its identity quest in the theater of the streets … striving for an identity that eludes them.” In our own times, this endless quest persists on social media.

McLuhan’s posthumously published, Laws of Media, which he coauthored with his son Eric, further developed the theme of how technological change, when pushed to its limit, can cause “reversal” in history. This law of reversal can in turn transform whole environments. Just as a nation-state that emerged in the print age can revert into a tribalist polity in the electronic age, an artificially contrived identity can undergo a similar change. Radical feminism’s denial of natural gender differences has flipped into male-dominated transgenderism, whereby trans-women now dictate to natural-born women what it means to be female. None of this would surprise McLuhan.

McLuhan’s prediction that all of us would become “reactionaries” who oppose rapid technological change has not yet come to pass. But for those who wish to stay awake, his sage advice holds: “If we keep our cool during the descent into the maelstrom, studying the process as it happens to us and what we can do about it, we can come through.” To the very end, the reactionary philosopher of media refused to let the juggernaut roll over him.

Source: Chronicles

Comments

Post a Comment