how we know what isn't so

how we know what isn't so

a look at the difficulty of knowing what you just measured

i have long been fascinated by the manner in which so much of what we “know” simply “isn’t so.” grand myths and misperceptions proliferate through our culture, our models of the world, and even in our scientific understandings. someone does a bad study, makes some wild claims, and decades go down the tubes as whole fields get led astray into rabbit warrens and the consciousness and belief set of the populace gets wedded to some form of compelling crackpottery or other.

there’s always “data.”

there’s always a loud proclamation.

and because it’s some simple seemingly telling claim, everyone jumps on board. mostly, they want to. people love stuff like this. they love “big, simple facts.”

but a shocking amount of it is just plain bunk generated by slanted study. this is sometimes unwitting, sometimes deliberate, but the effect is always the same:

you get told a big simple fact that is just plain wrong.

and more often than not, it’s because it was not clear what was really being measured.

because the world is hopelessly multi-variate.

and isolating them in complex systems is incredibly hard.

but what’s really interesting is that even when you screw up, you often learn lots of very useful stuff if you peel it apart later.

sapolsky, who wound up being a world leading researcher on the effects of stress made his initial headway into this field while trying to study rats. he was just SO bad at handling rats that they were all getting sick and having problems even with placebos/in control groups etc. so his studies were junk. but he was smart enough to see it and realize that there was another variable in play, one that was, perhaps, even more interesting than what he had been trying to study.

mistakes were made, seen, and careers launched.

the problem is how rarely this sort of self correction occurs.

mostly, even when studies come later and refute the “big simple facts” they just get ignored.

here’s a great example: everyone remembers the “addiction” studies that were everywhere where rats would keep hitting a feeder bar for cocaine or heroin and fail to eat until they died. it was made into a “big scary” about drugs and how addictive they were and how dangerous that was.

the problem is that it was total nonsense. that’s not what it proved at all. because that’s not what it was really measuring.

rats are social animals. trapped alone, they are miserable.

they wind up drug addicts because they are dejected and desperate.

but offer them an enriched environment especially one with other rats in it, and they forgo drugs and go hang out with their pals. because they like it better.

how much better? A LOT better.

this is a seriously stacked deck where even already “addicted” rats deprived of contact chose “rat” over “drugs” more than 9 times in 10.

that’s quite a different story that the one most of us know. and the implications are massive. we thought we were measuring addictiveness of substances. but what we were really studying is how a highly social animal responds to stress, loneliness, and fear.

and this is knowledge that would have come in handy to have had in common currency back in 2020, no?

this was a highly predictable outcome if one knew what was instead of what wasn’t so. it also massively informs effective ideas on drug treatment. humans with strong social networks and strong social graphs act like rats. they are far less prone to fall into this sort of addictive spiral. but if your whole graph are drug users burying pain and loneliness and you’re loving the company and the misery or you’re just plain all alone?

well, we saw how that went.

and this issue is just insidious because it’s simply freaking everywhere.

some are so stupid they’re easy to spot:

but some of them wind up passing muster because it’s not inherently obvious what an answer (or a problem) might be.

a great example is “calories restriction to ultra low levels extends lifespan.”

much of this was based on the famous wisconsin study on rhesus monkeys where primates fed a diet with 30% fewer calories than the control group naturally sought to eat left to its own volition lived longer with only 13% dying from age related causes vs 37% in control.

this seemed like a big deal and many fad diets were born.

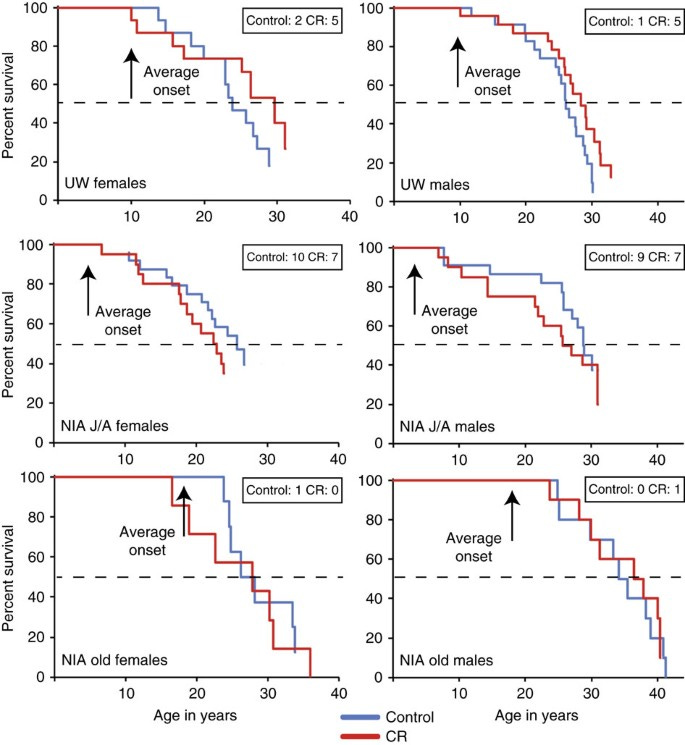

but, in the end, it was just plain wrong and failed to replicate in a similar study done by NIH. in that study there was no real difference in the curves and, if anyhting, control fared better than restricted.

you can see it here: (source, nature communications)

and there is a clear reason they diverged. (that we’ll get to in a minute)

and predictably the NIH has no idea what it is and publishes a pile of tepid pabulum to bury the real finding.

their generalized and hand wavey “well, i guess it’s a lot of stuff” outcomes claims about “complexity” look like unsubstantiated junk.

but they are right about the differences being important in helping us better understand the situation.

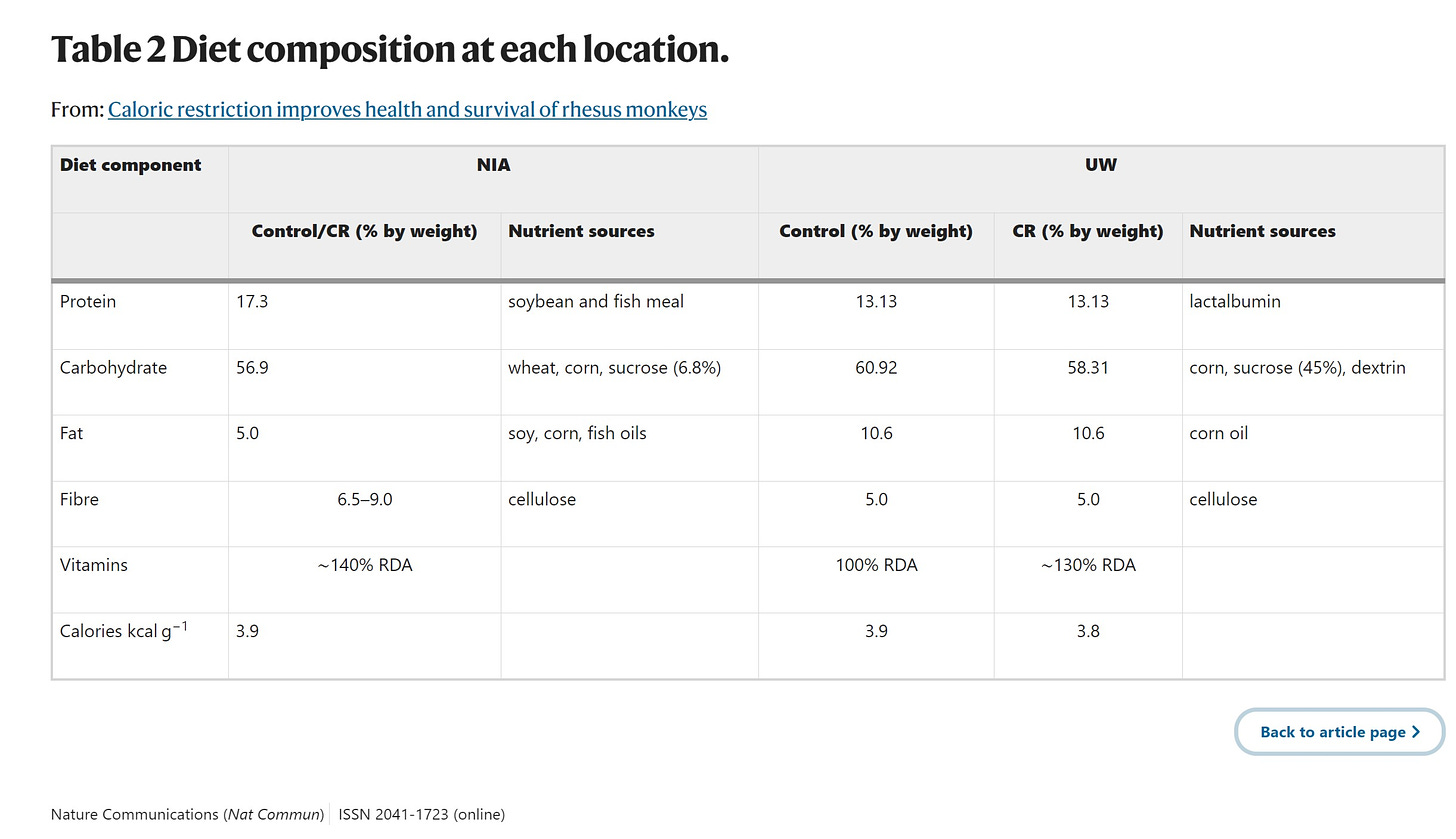

because there was one clear, massive variance in the two studies and it’s almost certainly the source of materially all the variance:

the wisconsin monkeys were basically fed nothing but the simian equivalent of junk sugar cereal (a commercial monkey chow) and the NIH monkeys were fed a less refined diet of more natural foods. the “macro-nutrient” levels may have look similar at very low resolution, but they were wildly different.

the diet of the NIH monkeys was 4% sugar.

the diet of the wisconsin monkeys was 29% sugar.

and that’s the ballgame.

what passed for “food” in wisconsin was basically about the same as eating nothing but “froot loops” your whole life. (31% of calories from sugar)

gee, i wonder why over 40% of the wisconsin control monkeys developed insulin resistance and prediabetes vs just 14% of control at NIH?

yeah.

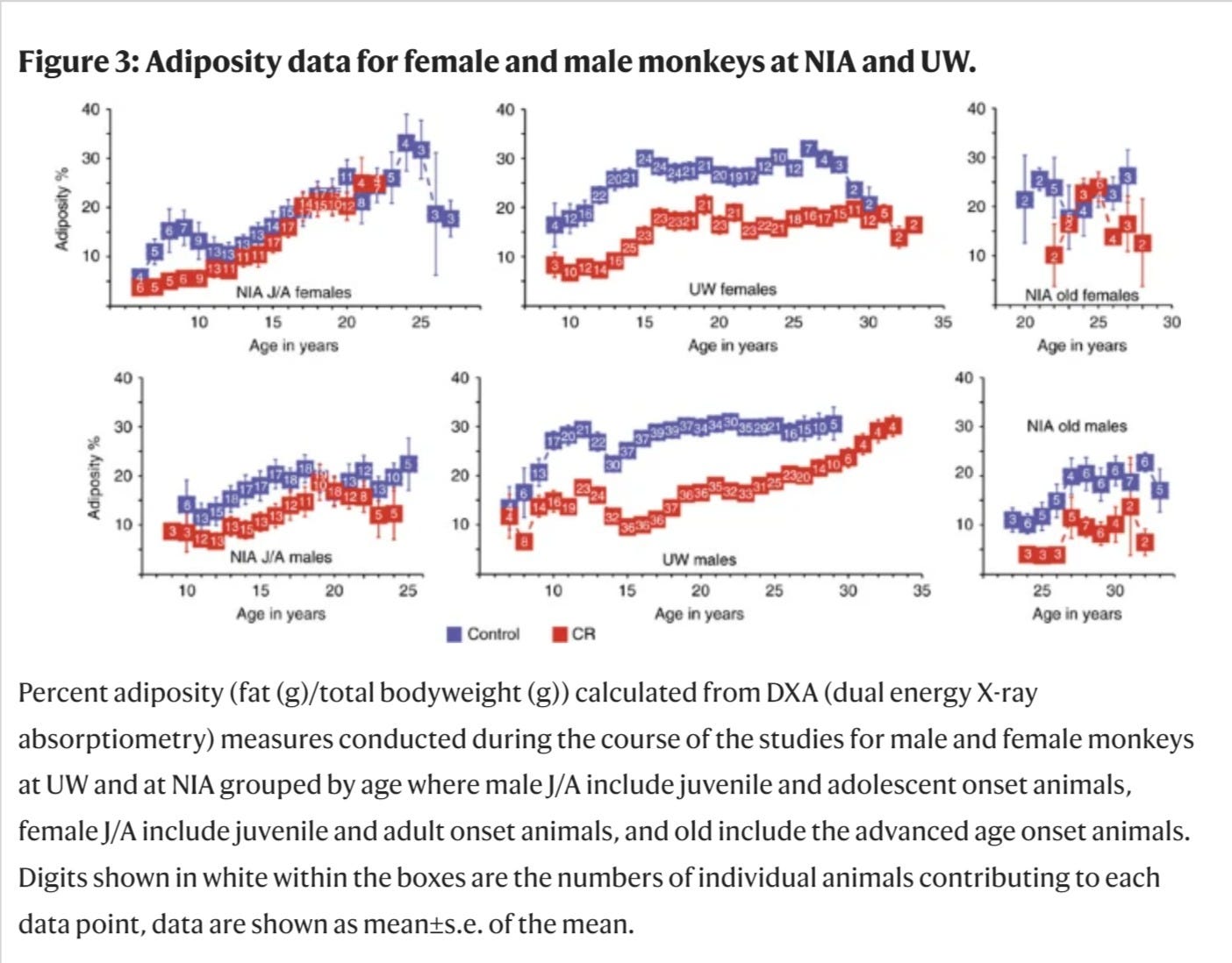

and you can flat out see the results of this dietary structure:

adiposity is just “body fat.” look how much lower the “old males” in particular were in the NIA control group vs wisconsin control group.

in the lifespan charts, it looks like the NIH “old males/females” control groups also lived longer than the WI control groups, but i’m not sure if that can be read that way as it may be a sort of left truncation selection that is only letting the healthiest through from “young.” i’m not quite clear how they structured that. (if anyone knows, please chime in.)

but the take away here is clear:

composition of calories matters in terms of health.

calories per kg of weight were basically identical in the control groups. but one was fatter and ~3X as prone to diabetic issues.

if you load up on sugar, it’s not going to go well for you. you’re just not evolved to eat that much fast carb and high calorie foods devoid of nutrients. and it plays hell on your gut biome which in turn affects metabolism, immune function, and mood.

and the wisconsin study was not measuring the effects of low calories, it was measuring the benefits of not bludgeoning your endocrine system with piles of processed sugar.

and this sort of mistake can have huge societal effects.

when everyone suddenly decides that “low fat high sugar” foods are the new new thing in the 80’s, well, you get a huge spike in obesity and type 2 diabetes that is still getting worse.

the more you look for this, the more you’re going to see it absolutely everywhere.

humanity runs off half cocked on this all the time.

and so any given study or datapoint needs to be treated very carefully. they are all potential and even likely sources of once more “knowing what isn’t so.”

but when we triangulate between them, in the cracks and differences, we can often find kernels of actual useful knowledge.

that’s the practice one ought to cultivate if one would seek wisdom.

Comments

Post a Comment