Marija Gimbutas

Marija Gimbutas

Kurgans, Vaginas, and Lizard People

Imagine if one evening Stephen Hawking appeared on the History Channel to announce that, based on his research, he had determined that aliens had in fact not only built the pyramids, but also created a utopian world civilization, and that they had left clues to their presence in the form of circles and triangles carved and painted all over the place- anytime you see either, you know it’s the Saucer Men. Imagine that he also stated confidently that he could confirm this information by reference to his intuition concerning outer space. While, like the rest of America, I would have absolutely loved to have seen that, it unfortunately didn’t happen. Instead, the world got a somewhat more puzzling train-wreck in the form of Marija Gimbutas.

I say the world; Hawking is famous, a household name. Gimbutas is not, but should be. It is to her more than anyone else that the credit should be given for solving one of the great mysteries of the human past; who were the first speakers of Indo-European languages, the most ubiquitous language family on Earth, and from where did they come? Her life story is fascinating for many reasons, but the sheer arc of it is perhaps the most interesting and instructive. Gimbutas was born into prominence, fell into poverty and obscurity fleeing multiple armies and oppressive governments, worked her way through sheer force of will through a range of demanding academic programs in multiple disciplines, became a superstar through a series of groundbreaking works that culminated in solving the problem of IE origins, and then traded all of that in at the end of her career to write a collection of New Age feminist cringebait that had her peers and colleagues doing the academic equivalent of the awkward collar tug in print.

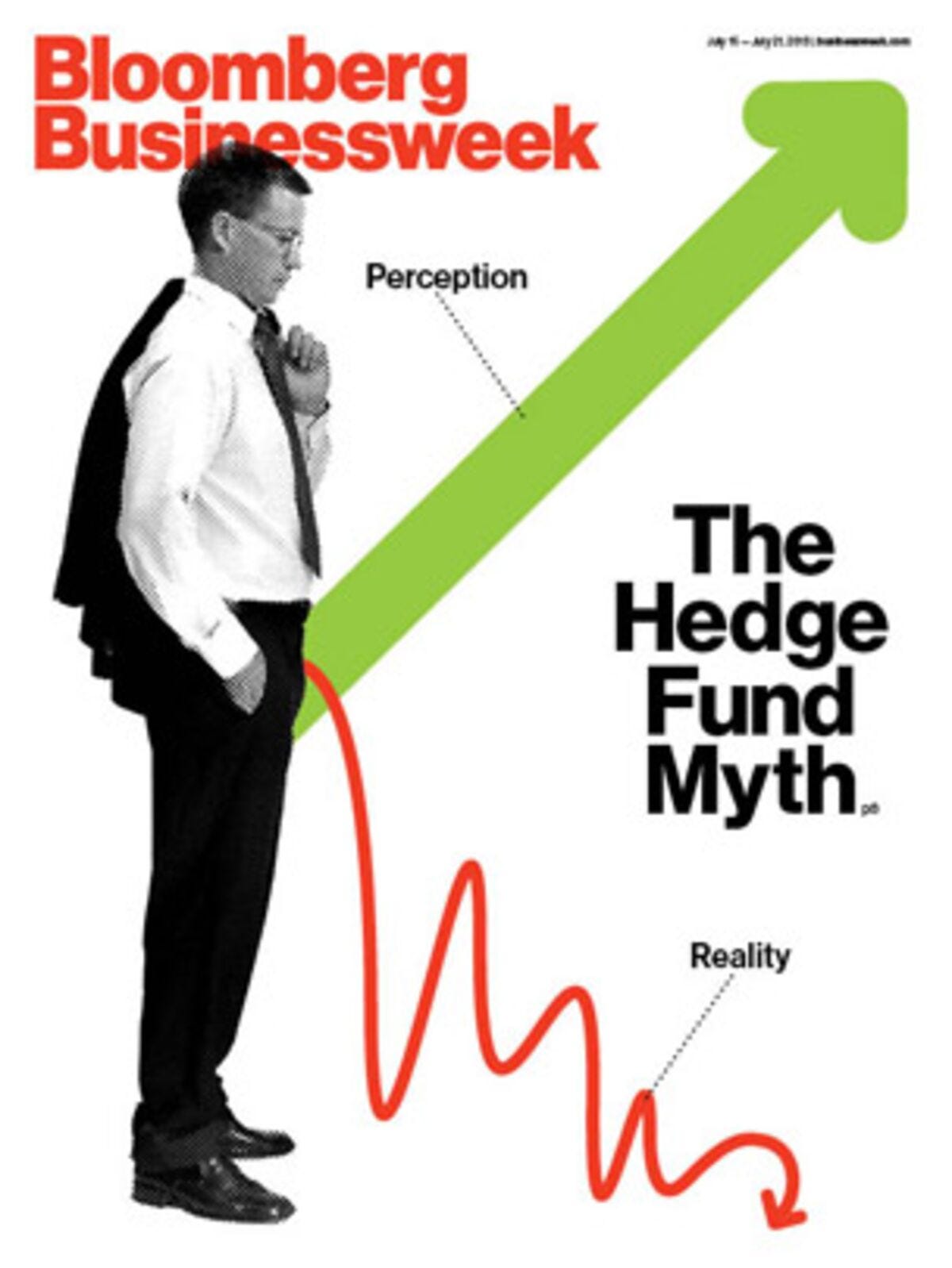

(This move)

Marija Gimbutas was born in 1921 in Vilnius, then part of the Republic of Central Lithuania (not to be confused with the Republic of Lithuania), one of the unstable micro-states to emerge after WWI. The country of her birth came into being the year before she was born and was gone before she would have said her first words, being absorbed into Poland. Despite the unstable political situation around her Gimbutas remembered her childhood fondly. Her parents were well-educated (her parents were both doctors) and they associated with leading Lithuanian intellectuals, her mother maintaining a salon-like atmosphere in the home. Gimbutas herself received a fine education, especially for a woman at the time, and had the situation in Europe been more placid, it is likely she might have gone on to become a leading member of the Lithuanian intelligentsia herself. But it was not to be.

In 1939, the Republic of Lithuania (not the Republic of Central Lithuania- that’s part of Poland now) signed a treaty with the Soviet Union in order to preserve its independence from Germany. The Soviets promptly invaded and occupied Lithuania themselves, Stalin having shortly thereafter become pals with Hitler, joining with him in next invading Poland. The Republic of Lithuania became the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1940 (keep up). This happy friendship between history’s complex antiheroes lasted until June of 1941, when Hitler rolled through both Poland and Lithuania on his way to launch Operation Barbarossa, the largest invasion in history, four million men sent against the Soviet Union as part of the fuhrer’s 5D-chess plan to save the Aryan race by holding the world’s largest white people killing contest.

(BRIEF DIGRESSION: They made a movie in Pakistan in the 80s where Hitler escapes the atomic bombing of Germany (just go with it) and flees to, where else, rural Pakistan, where he sires a son, Hitlar, who creates a village-wide reich complete with kung fu, psychically controlled bears, and numerous musical numbers. It’s not a comedy. You seriously need to watch this movie; ignore that it’s in Punjabi. The action speaks for itself, as does the theme song. Back to the story.)

Gimbutas was right in the middle of all this, and her idyll ended at the very moment her adult life was beginning. War did little to slow down her academic ambitions, however, nor her family life; she married and had children while studying archaeology, linguistics, religion, ethnology, folklore, and literature at the University of Vilnius, earning a master’s degree in 1942, then, fleeing the advancing Soviet Army into the best available option of Nazi Germany. There had long been enormous interest in Indo-European studies in German Universities, and Gimbutas was able to both refine her interests along these lines and broaden her intellectual range and methodology. She studied at the University of Vienna off and on, translated her work into German, and earned a doctorate at the University of Tübingen in 1946, fortunate to land a spot at a college that had not been bombed by the Allies. After the war, she conducted postgraduate research there, and then, in 1955, moved to America to work at Harvard University.

Gimbutas would not be the first to discover that there were downsides to being at an elite institution. Her role was to essentially be the foreign help, doing the translation scutwork that would free up her betters for crew and dinner parties. For her first few years she received little funding or institutional support. Despite this, she managed to publish the groundbreaking and monumental work that made not only her reputation, but revolutionized IE archaeology.

The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Part 1, published in 1956 was something only she could have written. As Joan Marler notes in “The Life and Work of Marija Gimbutas,”

Most archaeologists are specialists of a specific region, are rarely trained as linguists, and often cannot read archaeological reports in languages other than their own. Marija Gimbutas was therefore in a unique position to develop an encyclopedic knowledge of European archaeology.

While for Dumezil understanding the Indo-Europeans primarily meant a deep dive into languages and myths, Gimbutas sought a still more comprehensive approach, uniting traditional methods with archeological field work and anthropological studies. She knew seven languages and could read some twenty, and with her background among the elite of a country now behind the Iron Curtain, she had access to contacts and resources her American and Western European colleagues lacked. Absorbing the full range of research on offer, and drawing on existing hypotheses about IE origins, Gimbutas offered a theory that sought to explain one of the most enduring problems in IE studies: who were the original Indo-Europeans and where had they come from? Her answer: they were the builders of the great kurgan grave-mounds of the Eurasian steppe, in what is now Ukraine. They had come from there, in several waves, identifiable from distinct archaeological remains. Groups of these people had invaded Europe around 3,000 BC, becoming at least in part the ancestral populations of modern European nations, and their language was ancestral to most of those spoken in Europe.

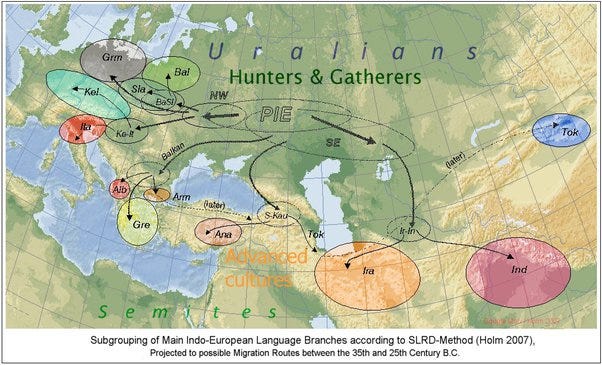

(The only link to this great map is through Quora.)

In this scheme, later expanded upon by others, there were three groups that ultimately came to inhabit Europe in the prehistoric era. The first were the Pleistocene-era Hunter-Gatherers, subdivided into the majority Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG), along with smaller populations of Eastern Hunter Gatherers (EHG), and Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers (SHG), who were a mix of the first two groups. Around 6,000 BC, groups practicing agriculture began to migrate to Europe from Anatolia; these settlers were known as Early European Farmers (EEF). These two groups interacted in various ways, sometimes the EEFs displaced the WHGs, sometimes the latter came to rule the former as an elite, sometimes the EEFs abandoned farming for the WHG lifestyle. For the most part, the blending of these two cultures led to societies where agriculture and settled life were the norm, and this way of life, along with its material culture, was what Gimbutas was to label “Old Europe.” The third group to enter Europe derived from EHGs from the northern forests of what is today Russia and Caucasian Hunter Gatherers from the eponymous region (CHG). These groups had blended, formed a society on the steppe centered on horse-facilitated pastoralism, and burst out onto Europe in the fourth millennium. These were the Indo-Europeans.

(See, WHGs were diverse, so what’s your problem with mass immigration, bigot! Trust the science. Oh wait . . .)

Much of the confirmation for this would have to wait for later archeological developments, and Gimbutas’ ideas flew in the face of competing theories, then and now. Moving from least to most plausible, these include Nazi-tier speculation about Aryan homelands in Tibet, Antarctica, and Atlantis, Hindu nationalists who maintain that IE languages began in the Punjab, and Colin Renfrew’s Anatolian Hypothesis, which posits that the Indo-European languages evolved from the tongue spoken by the EEFs. Under this scenario, if a steppe invasion took place, it was small-scale and the invaders were the ones who absorbed the linguistic change. This last theory still has adherents; more on that in a moment.

Gimbutas’ work made her a legend in the tiny world of IE studies. She was offered a professorship at UCLA, where she would remain for the rest of her career. Jaan Puhvel, the foremost advocate in America of the theories of Dumezil, was already a professor there, and became a close friend and collaborator. She mentored the work of a number of IE scholars, most notably J. P. Mallory, perhaps the most prominent Indo-Europeanist writing in English, and with Gimbutas the founder of the Journal of Indo-European Studies. She produced a series of books in the two decades that followed that served to further cement her reputation as one of the most resourceful and interesting scholars in the country, if not the world.

Interestingly, however, for Gimbutas the most important part of the IE story was not the horse lords of the steppe, but the people they conquered, Gimbutas’ Old Europe. In the early years of IE studies nationalist sentiment, romanticism, and related ideas created a kind of presupposition that the Indo-Europeans were hard, warlike invaders who willed their Nietzschean power all over . . . some blank slate, docile farmers who were probably lucky to get totally dominated. This gap in the story of the conquered fascinated Gimbutas; in time it would consume both her and her academic reputation.

Based on numerous archaeological field expeditions, folklore collection, ethnography, linguistic analysis, and thorough study of myth and religion, Gimbutas increasingly came to believe that Old Europe represented not merely a different society than the one that conquered it, but its very opposite. While the IE invaders were patriarchal, hierarchical, militaristic, and mobile, worshiping gods of the sky and war, the people of Old Europe were sexually and politically egalitarian, peaceful, and rooted to the land through a complex spirituality centered on female deities representing nature and fertility. In 1974, Gimbutas published The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe (originally Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe; feminism intervened between editions), which laid out these theories in ways that could charitably be called ‘elaborate’ and was received in a polarizing fashion.

Gimbutas is often described as a feminist, but this is misleading (her last collaborator, herself a feminist, rejects the label for Gimbutas; Gimbutas, for her part, hilariously referred to the feminist scholar as her secretary to visitors). While Gimbutas was raised in a liberal environment in Lithuania, she was, up until nearly the end, a careful and dispassionate scholar seemingly indifferent to political activism. Her obituary notes that her work was “rather in advance of the great tide of feminist writings in the United States and Britain;” in other words, it was she that helped kick off a massive wave of feminist anthropology, archeology, myth theory, and religious studies, rather than being under its influence. At the places where feminism intersected with spirituality (i.e. California in the 70s) Gimbutas’ work became a runaway hit, spawning everything from scholarly books and articles to New-Age tinged self-help literature. The notion that there had once been a golden age of matriarchy in Europe (this was the meme that spread, though Gimbutas had in fact argued for equality rather than female domination), which was destroyed by violent male chauvinist pigs, was just too good to not be true. The modern Goddess Movement, while it has antecedents in romanticism and twentieth century occultism, owes its final form to Gimbutas.

(They’re not only edgy, but original.)

The problem was, as her increasingly uncomfortable scholarly peers kept pointing out, Gimbutas’ method left much to be desired. Step one went fine; she gathered an enormous amount of data on pictograms and artifacts and such, carefully cataloguing all of the symbols depicted therein, and cross referencing them with similar objects by location and time period. Step three was her writing voluminously about the meaning of these symbols and the nature of the spirituality they represented, one which largely centered on female reproductive power. You may have noticed the problem- step two, demonstrating what the symbols mean through careful analysis of text and context, was completely missing. Gimbutas simply asserted that she knew what the symbols meant, and what they meant was vaginas, and the vaginas of the goddesses were everywhere.

Sometimes this was almost comically absurd. Among other things, her list of symbols of the feminine divine included bulls’ heads (the horns were said to resemble fallopian tubes) and rams as representative of the bird goddess’s female sexuality. Like a Freudian on a phallic scavenger hunt, she saw mysterious lady parts under every rock in Europe, although interestingly, she never seems to have made the connection with the obviously womb-like kurgans of the IE Chad invaders. Wavy lines on a potsherd = water = fertility = goddess, same with circles (vagina), M-looking symbols, etc. It was all very groundbreaking, even revolutionary, if one accepted the basic premise of the total accuracy of a brilliant PhD’s woman’s intuition.

(Move along, Freudians.)

None of this seemed to trouble her as she went from being the Marija Gimbutas of the IE world to the Erich Von Däniken (or David Icke, for you young people). Sadly, this comparison isn’t really an exaggeration; the exact same method of research and interpretation gives you sacred orifices, ancient astronauts, or shape-shifting reptilian overlords. It wasn’t that she jumped on board with the yoga moms writing poetry to their uteri, nor was she unaware that no one accepted her theories. She just seemed to take it in stride. Most people who encounter her in the period comment on her grandmotherliness, warmth, and openness, though she was not unwilling to debate her views, or even show up to argue in their support wherever they were questioned. Nonetheless, it was clear that she was no longer considered all there. Her second edition of G&GOE in 1987 received a forward from Joseph Campbell, a popular authority, but no one’s idea of a rigorous scholar. Mallory et al. were not forthcoming with praise.

Why she committed scholarly seppuku is debated. Gimbutas spoke often about a visceral horror of war and violence, understandable given her background. Knowing that most of her peers in her homeland had either been killed in conflict or in various murder camps made her doubtful of the modern world. Like Dumezil, she dwelled in the past so often it was no less real than the present. But while Dumezil saw something to admire about the people of the steppe, Gimbutas physically recoiled from the weapons she excavated from the kurgans. She longed for a world that held more promise so strongly that she started to sense its presence in Venus of Willendorf figurines. When she died of cancer in 1994 at 73, her biggest fans were those who knew the least about her most solid work. It was widely held that while she had been a brilliant scholar, she had gone off the deep end, a cautionary tale about seeing things that aren’t there and shaping things to suit preconceived notions.

and yet . . .

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out one very important point about how Gimbutas’ later theories were received. Her basic premise had two parts- hippie commune Europe, invasion of Aryans harshing everyone’s buzz. Apart from her issues of interpretation of symbols, scholars pointed out that the archeological evidence argued against her assessment of Old Europe; there were obvious indications of warfare, of male gods, of hierarchy, all that. As Lawrence Keeley points out in War Before Civilization, there are vanishingly few societies anywhere that could be called peaceful; this certainly could not be said of any whole continents, and absolutely not for tens of thousands of years, as would be the case under Gimbutas’ schema. That much is true and has held up. But it is only just to point out that the same people who criticized her for part one of her premise also denied the validity of part two. In “The False Goddess and the Lost Paradise” classicist Bruce Thornton pours cold water on the whole idea of an IE invasion of Europe, preferring as more rigorous Colin Renfrew’s theory of an indigenous origin of the IE languages. (Note, both Thornton and Renfrew are political conservatives). Mallory hedged in this regard as well, as did many, many others. Pots-not-people exerted a lot of power in the post WWII world, a zeitgeist wherein people did not want to believe that bad-guy conquerors could win out and impose their culture on peaceful Euros.

They were all wrong, and Gimbutas was right, not about Neolithic Europe being ruled by happy co-ed drum circles, but certainly about the invasion. Genetic evidence clearly shows a really big shift in the male side of the European gene pool at exactly the point predicted by Gimbutas. Just as she had said, a new race of patriarchs had come to dominate Europe, bringing not only their pots, but their horses, chariots, and swords. Despite the limitations of the evidence, Gimbutas still saw through to the truth while her detractors went with the consensus. Perhaps the lesson here is more complex than simply avoiding becoming a dotty old woman seeing a vagina in every crack in a stone.

Perhaps a scholar can reach a level of expertise such that intuition really is a valid way of approaching the evidence.

It makes one wonder about the lizard people . . .

Source: Librarian of Celaeno

Comments

Post a Comment