AI Cameras Took Over One Small American Town. Now They're Everywhere

AI Cameras Took Over One Small American Town. Now They're Everywhere

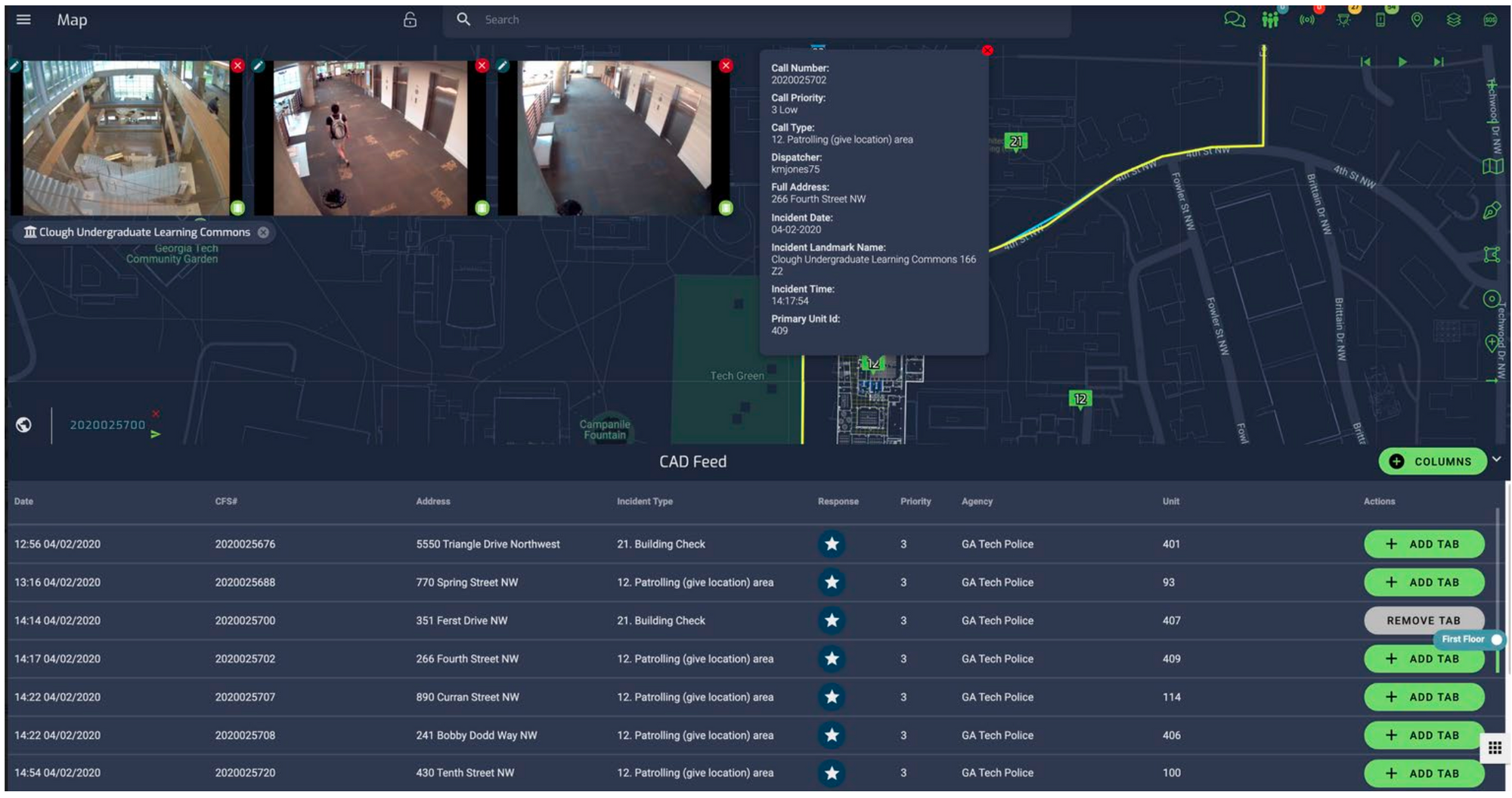

Spread across four computer monitors arranged in a grid, a blue and green interface shows the location of more than 50 different surveillance cameras. Ordinarily, these cameras and others like them might be disparate, their feeds only available to their respective owners: a business, a government building, a resident and their doorbell camera. But the screens, overlooking a pair of long conference tables, bring them all together at once, allowing law enforcement to tap into cameras owned by different entities around the entire town all at once.

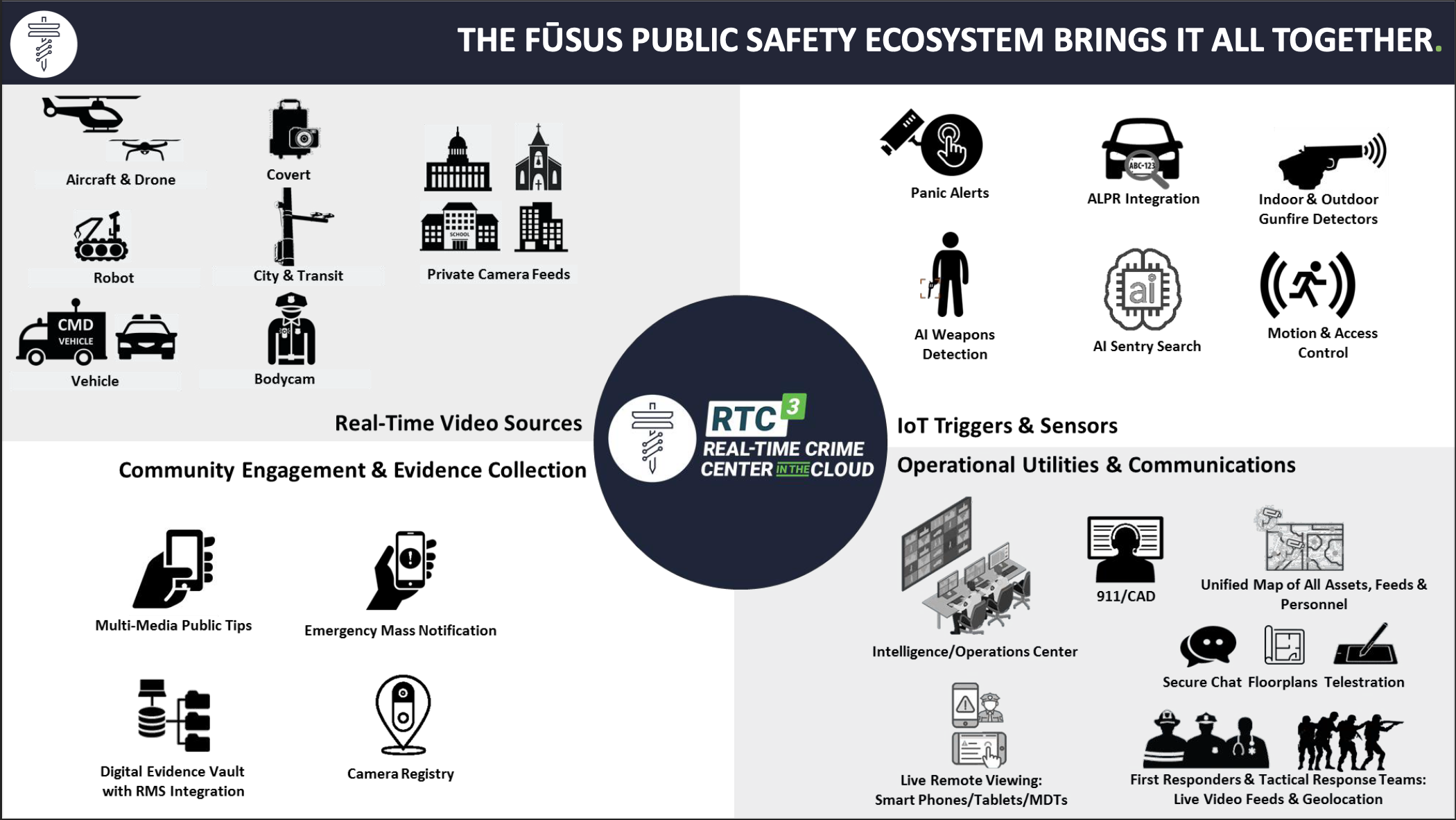

This is a demonstration of Fusus, an AI-powered system that is rapidly springing up across small town America and major cities alike. Fusus’ product not only funnels live feeds from usually siloed cameras into one central location, but also adds the ability to scan for people wearing certain clothes, carrying a particular bag, or look for a certain vehicle.

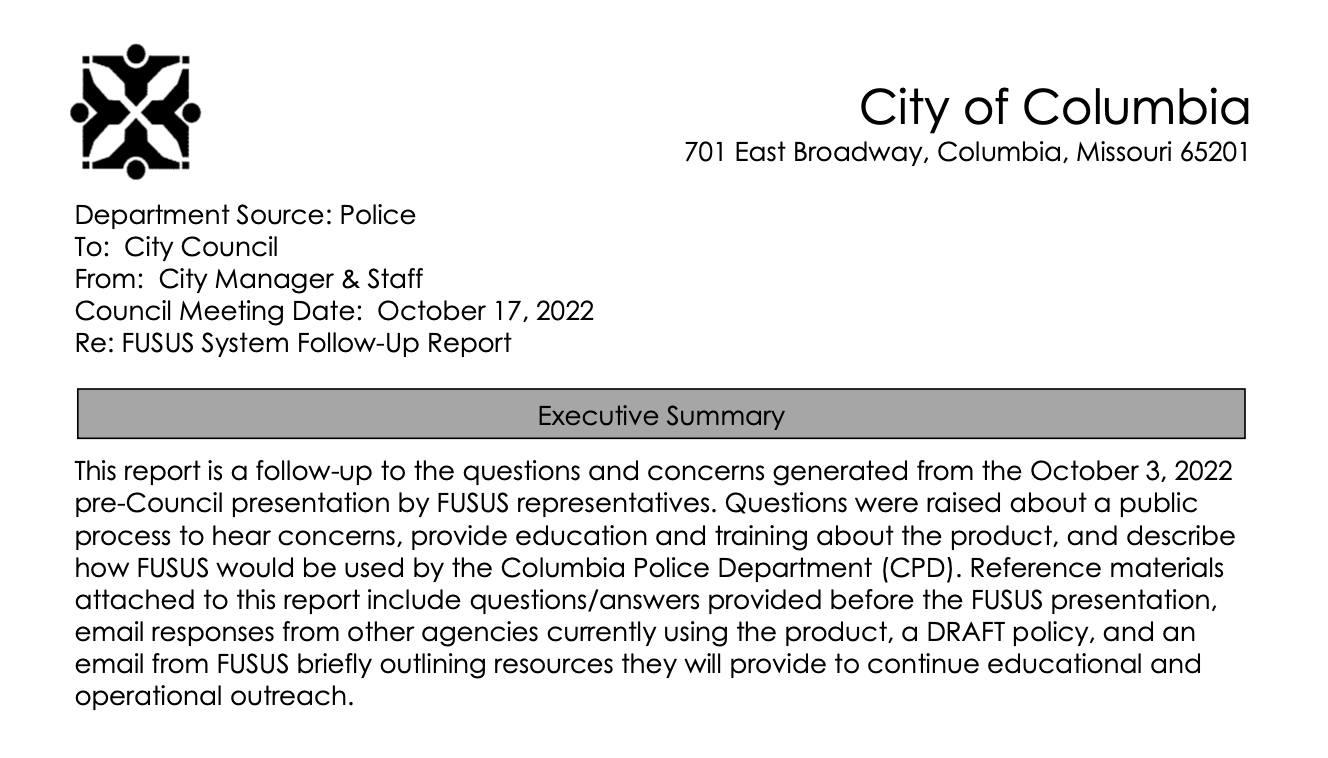

404 Media has obtained a cache of internal emails, presentations, memos, photos, and more which provide insight into how Fusus teams up with police departments to sell its surveillance technology. All around the country, city councils are debating whether they want to have a system that qualitatively changes what surveillance cameras mean for a town’s residents and public agencies. While many have adopted Fusus, others have pushed back, and refused to have the hardware and software installed in their neighborhoods.

In some ways, Fusus is deploying smart camera technology that historically has been used in places like South Africa, where experts warned about it creating an ever present blanket of surveillance. Now, tech with some of the same capabilities is being used across small town America.

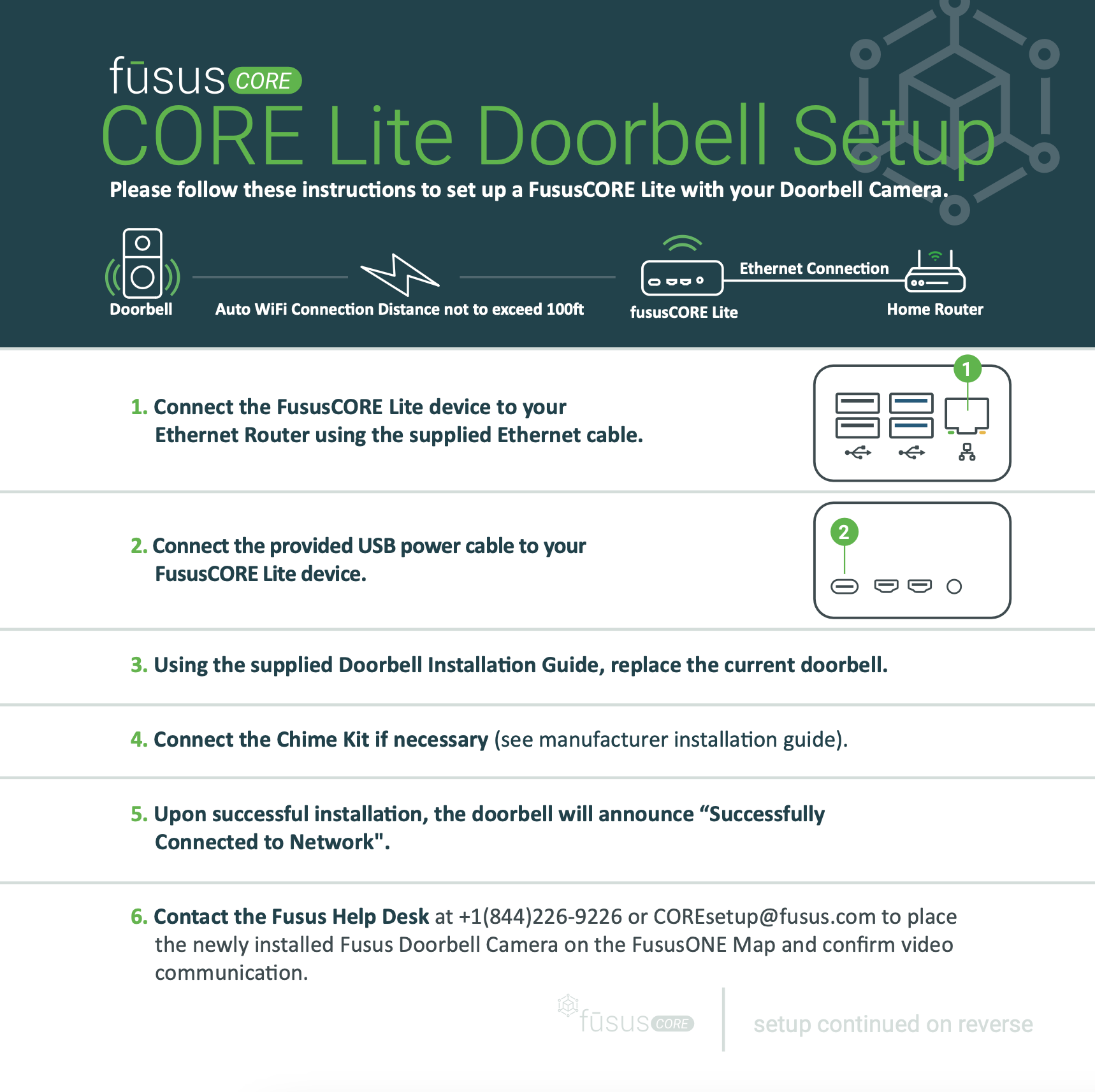

Rather than selling cameras themselves, Fusus’ hardware and software latches onto existing installations, which can include government-owned surveillance cameras as well as privately owned cameras at businesses and homes. It turns dumb cameras into smart ones. “In essence, the Fusus solution puts a brain into every camera connected with the system,” one memorandum obtained by 404 Media reads.

“The lack of transparency and community conversation around Fusus exacerbates concerns around police access of the system, AI analysis of video, and analytics involving surveillance and crime data, which can influence officer patrols and priorities,” Beryl Lipton, investigative researcher at activist organization the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), told 404 Media in an email. “In the absence of clear policies, auditable access logs, and community transparency about the capabilities and costs of Fusus, any community in which this technology is adopted should be concerned about its use and abuse.” 404 Media obtained the documents through voluminous public records requests with law enforcement agencies throughout the U.S. Lipton previously carried out a similar project for the EFF.

One agency that provided a large number of records to 404 Media was Starkville Police Department in Mississippi. As Fusus and the college town agency worked together throughout 2021, they discussed camera placements at student apartment buildings, a storage business, multiple street cameras, inside a parking garage, and an upscale rental community. In one email, a Fusus network support engineer asked Sergeant G. Brandon Lovelady, Starkville PD’s public information officer, if he could go to one of the student apartment buildings to gather floor plans of the complex to assist with camera placement. After some technical hitches and paying their ISP an additional cost in order to properly configure the cameras, Starkville PD started to receive participating camera feeds, according to multiple emails. Fusus prices vary from $25,000 to $100,000 a year, according to the documents.

“So far the response has been amazing. We've had, specifically, the response from the business community has been there because I think that people that are in this industry and in the business industry know economic development and public safety go hand in hand,” Starkville PD chief of police Mark Ballard said on an episode of Fusus’ podcast published in March. “Our school systems, our churches, our places of worship, our kindergartens, they're all on board and becoming video-savvy and a part of the system,” he added.

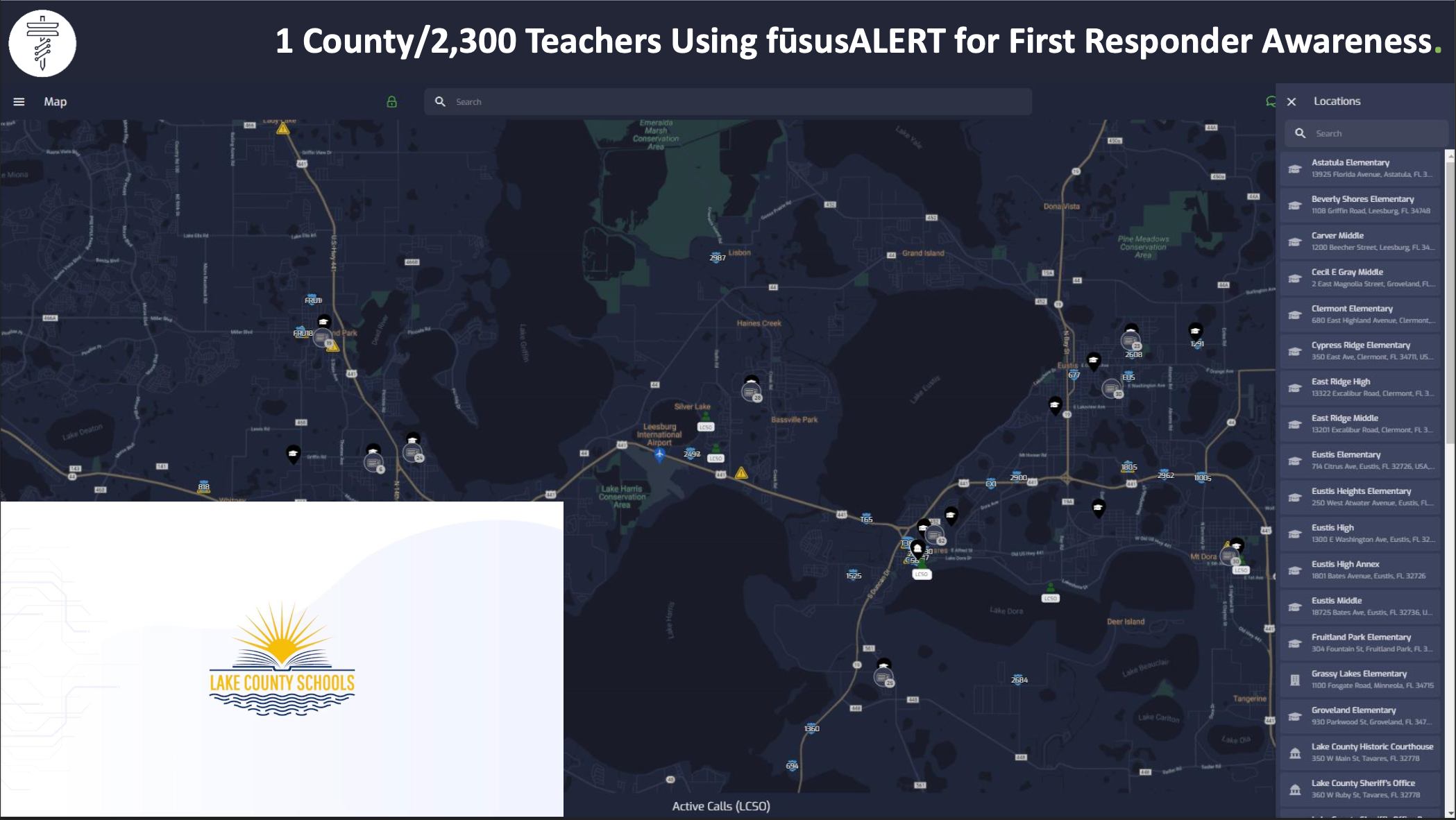

Whereas normally public and private security cameras are separate, with only their respective owners or administrators able to view any feeds, Fusus aims to bring all of that footage together in one place. That can include doorbell cameras, drones, robots, fixed surveillance cameras, helicopters, hidden cameras, police body cameras, and cameras in schools and churches, according to multiple documents. Police departments then gain access to a map interface showing all of the camera locations.

“Whether it’s a drone, a traffic camera, a private cell phone video, or a building security camera, FUSUS can extract the live video feed and send it to our Intelligence Center and officers in the field,” one memorandum from Elizabeth City, North Carolina, reads.

A GALLERY OF IMAGES OF THE FUSUS DOCUMENTS. IMAGE: 404 MEDIA.

That hardware, called SmartCORE, adds artificial intelligence to ordinary surveillance cameras and then allows them to detect different objects, vehicles, clothing, and “people.” The exact context or object being identified is unclear, but one screenshot included in a Fusus brochure shows a timeline interface with a camera feed and an attached “confidence” rating of 51.46%. The system can also integrate with gunfire detection systems and other internet-of-things sensors, another document reads.

Across media reports and marketing material online, there is confusion about whether Fusus has the capability for facial recognition or not. In multiple instances, Fusus has stressed its products do not have such a capability, including in a list of talking points obtained by 404 Media from a police department. But then a website for the reseller which provided Fusus to Starkville PD, a company called Pileum, says Fusus uses “advanced analytics, such as facial recognition.” A police chief in Columbia, Missouri, previously said that the software does have a facial recognition feature, but that the police would not use it, according to a report from local outlet KBIA last November. Fusus did not respond to multiple requests for comment from 404 Media, including one asking to clarify this point.

The cameras also turn into automatic license plate readers (ALPRs), able to read the plates of passing vehicles, creating a record of what car was at a specific location and at what time.

On top of bringing the camera feeds themselves together, Fusus aims to overlay and combine this information with more data, such as active calls for service and the geolocations of officers in the field.

According to a document comparing the different pricing models, agencies that sign up to the “Pro” and “Enterprise” versions get a “press release,” “hand-out cards,” and “promotional poster” as part of the package. One of those promotional posters obtained by 404 Media says camera feeds can be configured to share their feed all of the time with law enforcement, be automatically activated by a trigger, or “only on emergency alert.” With the Starkville PD, an email shows Fusus’ chief strategy officer also providing the department with a Powerpoint Presentation for “community marketing.”

In part that outreach is because Fusus and its customers need town residents and businesses to hand over access to their camera feeds. Fusus has created multiple websites, such as “Connect Atlanta”, “Connect Starkville”, and “Connect Orange County” where visitors can register their camera, letting investigators know where it is located, and then “integrate” their camera, which provides “direct access to your camera feed,” according to one of the sites. The sites are run by Fusus, but include the law enforcement agencies’ logos, blurring the line between whether it is a commercial or a public agency service.

A pop-up on the site says “I acknowledge that in order to participate in this program I will have to purchase equipment from FUSUS and pay any associated costs to access the technology required to transmit data.” The pitch to camera owners, according to the promotional poster, is that the owner’s own location will be more secure, and the police will be able to access the feeds in case of a crime. Those devices can range between $350 and $7,300.

Starkville PD’s integration with the community went further than a few posters. In one email, Lovelady said the police chief was looking for material to share with Mississippi State University and the regional manager of a bank. “Both have long and deep community ties,” Lovelady wrote. Another email shows a Fusus “community connect advocate” asking the Starkville PD for information on who handles the city’s Facebook account “so we can start making ripples through social media on the program.”

According to the Connect Starkville website, the city now has more than 480 integrated cameras that connect to the Fusus network and which can potentially be accessed in a city with a total population of roughly 25,000 people.

Lee Upchurch, a former law enforcement officer who has worked on Starkville PD’s real-time intelligence center, said on the same episode of Fusus’s podcast the connected cameras have led to quicker results. “If we have a guy that walks into a crowd with a gun and we pick him up on camera, our officers are on top of him in a matter of a minute, seconds, really, where back before the cameras we may would have to wait till the incident actually happens or somebody else sees it, or something like that,” he said. “It’s instant.” Starkville PD did not respond to multiple requests for comment, including one on whether this event actually happened.

Ballard added “It's allowed us to identify and be very effective in our investigation, and results in apprehension.” In a Fusus promotional video, the company says a school may decide to only automatically share its camera feeds during an active shooter situation. Or in an investigation, police can automatically request footage from all nearby businesses, the video adds.

Starkville PD is far from the only police department that has turned to Fusus. The EFF reported nearly 150 jurisdictions are Fusus customers. The Thomson Reuters Foundation, which reported on Fusus using some of EFF’s records, pointed to an IPVM report that said Fusus has helped network more than 33,000 cameras across 2,400 U.S. locations.

And Fusus is expanding internationally. In March, the company announced its launch in the United Kingdom. Dave Maass, investigations director from the EFF, told 404 Media that Fusus had a “huge presence” at the recent International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) conference. During a talk at the conference, the Royal Bahamas Police Chief logged into his account and opened an officer’s body cam live stream, Maass said.

Not all communities are embracing Fusus as swiftly as Starkville did. The city council for Columbia in Missouri, for example, voted 4-3 against purchasing Fusus, Columbia’s KBIA reported at the time. “It’s really disappointing to see how cavalier we’ve become about normalizing surveillance,” Second Ward Councilperson Andrea Waner reportedly said. The city is now revisiting the decision, however.

The dynamic with Fusus is similar to another playing out at the community level. Previously I covered how an ALPR company called Flock has become popular across the U.S. In that case the decision to purchase is often down to individual police departments or even homeowner associations.

Despite Fusus’s growing popularity, Lipton from the EFF still has plenty of questions about its rollout.

“Should law-abiding individuals be aware of constant law enforcement surveillance if they are in a Fusus-integrated grocery store or shopping mall? Should police departments be entitled to tie permit awards and other decisions to a business’s use of Fusus? Under what circumstances can officers access footage and what other analytics can be applied? Communities often don’t get a chance to discuss important issues involved in Fusus adoption,” she said.

Source: 404Media

Comments

Post a Comment