BURYING THE “CULTURAL MARXISM" TROPE

BURYING THE “CULTURAL MARXISM" TROPE

A SEASONAL STORY?

Elsewhere (see here) I have offered brief remarks on why I think it's mistaken to confuse the current managerial regime, and its woke ideology, with Marxism or communism. I won't rehearse all that here. I did though want to add a brief addendum to that argument with a few observations on so-called cultural Marxism. I think it was Jordan Peterson's popularization of this term that has contributed to its wide, if misleading (often lazy), use in recent years.

To be clear, there really has been such a thing as cultural Marxism. Not only though is cultural Marxism not the same thing as the managerial class regime and its woke ideology, but the former is by definition a critical rejection of both. To understand that dynamic, though, understanding the nature and purpose of cultural Marxism is required.

Before going into that, please indulge me a brief response to the recent flood of books claiming wokeism is Marxism, or communism, or maybe Maoism.1 Two arguments seem to have gained traction amid this flurry of echo chamber driven confidence.

1) They call themselves Marxists/communists, so obviously they are. Right? Really? So then Antifa is anti-fascist, right? It's what they call themselves. And so, by definition if they're anti-you, I guess you must be fascist. The theoretical ridiculousness of this claim is breathtaking. But it is matched in its breathtaking quality by the historical ridiculousness of the second recently popular argument.

2) The Marxism in woke is evident in the transposing of the former's oppressor-oppressed dyad into the latter. Seriously? Because I'm pretty sure that that same dyad informed domestic political conflict at least as far back as the Roman Republic. And probably back to Periclean Athens. In fact, I'm guessing some version of that social frame can be found in most reasonably complex human societies. Now of course Marx put his own spin on this old story, with his economism and dialecticism. Where is all that though in managerial wokeism? Rather than Marxism's belief that the current oppression is the midwife of the freer world being born, managerial wokeism offers us nothing but an endless battle for the unattainable world of zero-injustice, -discrimination, -hate speech, -carbon emissions, etc. No, the convenient rhetoric on both sides notwithstanding, managerial wokeism is not an expression of cultural Marxism. Though, cultural Marxism did warn against the path that has led us here.

While in a recent post I acknowledged the impact of the Frankfurt School’s progeny in advancing the current regime, it doesn't follow that the first-generation Frankfurt School was responsible for this legacy. That proposition is only sustainable by collapsing the Frankfurt School into Herbert Marcuse, a move that is as theoretically warrantless, and historically refuted by the facts, as it is common among the current crop of neo-red baiters.

Cultural Marxism emerged soon after the Russian Revolution compounded by the authoritarian turn of that revolution and the failure of communist revolutions in Germany at the end of WWI. Broadly speaking, the relevant analysis was that these failures were due to an economism within Marxist theory. Working class revolutionary conscientiousness could not be assumed to arise from class conflict over economic interests. A shift to focusing on the cultural wellsprings of consciousness was required.

Though there were plenty of differences in their analyses and proposed remedies, a rough association of thinkers who would become labelled as the Western or Critical Marxists included Rosa Luxemburg, Gustav Landauer, Georg Lukács, Karl Korsch, Antonio Gramsci, and Anton Pannekoek. The fundamental binding belief was that Marx’s superstructure could not be relied upon to follow alongside the economic base like a leashed pet. Culture, with its presumed conscientiousness molding force, had to be theorized on its own terms. Or, as many on "the right" are fond of saying these days: politics are downstream of culture. (As I’ve made clear elsewhere, including in my new book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, I don’t share these assumptions; I’m merely describing here the complex of historical beliefs.)

This “Western Marxist” intellectual tradition and its central axioms were the source of the Frankfurt School and its high theory of cultural Marxism. Elsewhere, I've gone into the Frankfurters, and my differences with them. So that too is something I won't rehearse here. For the purposes of this post, I'll just offer the following observations. Overall, their main response to this Marxist economistic problem was to emphasize the impact of instrumental and bureaucratic rationality. Drawing from Weber’s critique of rationality, they concluded that this Enlightenment legacy pervaded western culture, turning consciousness into the extension of such instrumentality. Culture became the enactment of such a mindset, manifesting the former as a technology of mind control operating at the level of cognitive function – though they wouldn’t have described it quite that way. (Again, reference to my new book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, is required to distinguish what I agree and disagree with here.)

Adorno’s notorious critiques of popular music and movies as blunting the mental faculties of its consumers is a famous example of this process. While he certainly attributed some of this effect to what he perceived as the mind-numbing banality of such cultural production, his deeper analysis was that this was the natural outcome of an Enlightenment rationalism that disenchanted the world through its technical administration. As Adorno put it in probably the most famous opening to any of his works:

Whoever speaks of culture speaks of administration as well, whether this is his intention or not. The combination of so many things lacking a common denominator – such as philosophy and religion, science and art, forms of conduct and mores – and finally the inclusion of the objective spirit of an age in the single word ‘culture’ betrays from the outset the administrative view, the task of which, looking down from on high, is to assemble, distribute, evaluate and organize.

Though our current crop of neo-red baiters is fond of invoking Herbert Marcuse as the grandfather of contemporary wokeism – and not without some justification – to leap from there to indicting all of the Frankfurt School, as do so many, is to excessively simplify. And indeed to, in the process, paint “cultural Marxism” with the brush of wokeism is groundless. If anyone was the intellectual leader of the Frankfurt School, it certainly was not Marcuse. Whether in practical or intellectual matters, that leadership was clearly in the hands of Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. Theirs were the most ambitious works of “critical theory,” and their 1947 classic, The Dialectic of Enlightenment, is almost universally heralded as the defining theoretical achievement of the Frankfurt School. So, again, reducing the Frankfurt School and cultural Marxism to the personal project of Marcuse is groundless.

And, as I’ve just explained above, cultural Marxism was an effort to rescue Marxism from its economism. Managerial wokeism though is an abandonment of Marxism, unless again your knowledge of history is so scant as to imagine that Marx invented the oppressor-oppressed dyad. The fundamental grassroots, emergence of emancipation is dissolved by wokeism into the instrumentalities of bureaucratically paternalistic social engineering. The dialectic midwifery of contemporary conflict dissolves into the perpetual pursuit by the administrative state of an infinitely receding set of zero-stasis goals: zero-racism, zero-covid, zero-carbon. Wokeism becomes the excuse for the relentless management of all human life by the authoritatively designated technical experts.2 Simply, wokeism is the legitimating ideology of a managerial technocracy which is the very embodiment of the object of the Frankfurt School’s critique of bureaucratic rationality.

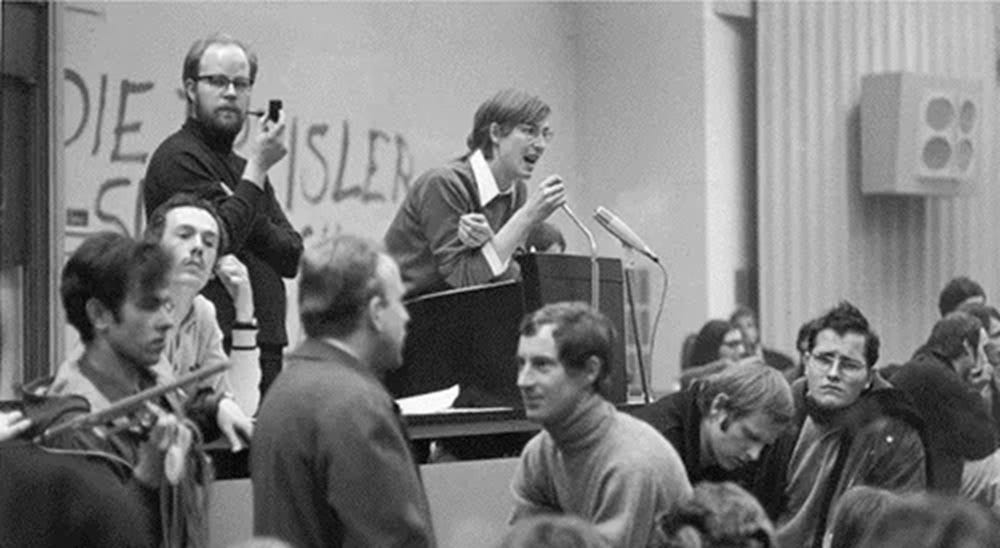

As I discuss in my new book (A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars), the 1960s probably constituted the phase transition of the spatial regime, building upon its victory in the longue durée French Revolution following WWI. And of course, a key aspect of that era was the student revolts occurring around much of the world, but especially in Atlantica. These student revolts were a central part of the consolidation of the technocratic managerial regime. It is interesting to look back on the rhetoric of those students to hear them mouthing anti-technocracy platitudes drawn from the erudite pages of the Frankfurt School of the 30s and 40s. Yet, they failed to recognize that the very institution they were trying to overthrow, the university, was at that time in fact one of the last remaining institutions left in the modern world not thoroughly colonized by commercialism and commodification. It remained a lone straggling holdout of a world more resembling the Medieval craft guilds than the relentless free market gesellschaft.

In this context then, it’s of interest to consider these key Frankfurt Schoolers’ attitude toward the student revolts of that time. We needn’t spend time on Marcuse; his enthused support for them is well known, and certainly not disputed by me. Instead, let’s look at what Horkheimer and Adorno had to say. The former had retired from active university life by the time of the student revolts, so we have less direct evidence on this front. But a fascinating collection of notes found among his papers give us some sense of his response to what was happening.

Among the published notes, there was only one direct reference to the student revolts, in which he perceives them as acting out Oedipal desires:

On the Student Movement: Unless I am mistaken, the purely psychoanalytical explanation of puberty refers to the complete internalization of paternal demands by the psychic substance of the adolescent. He now judges the father by his own morality, and rebels against him. Unless Freud already said so, I think it should be added that once the physical and reasoning powers of the young have developed to a certain point, they result in the negation of dependence, in the detachment from older persons, as is also true among many animal species. The more the traditional ties in the family, and therefore conscience, recede, the more decisive this moment becomes.

This largely Freudian reading of the students was not uncommon among members of the Frankfurt School. Though Horkheimer’s connection of the idea with the traditional family is an interesting one, very much in keeping with his own concern with the historical conflict between modernity and tradition. Perhaps though further, and for our purposes more relevant, insight can be gathered from some other notes he recorded around this time. For example, in a remark that seems directed at the self-realization ethic of the 60s generally, but the students particularly:

The unfolding of subjects in a variety of directions, the autonomy of many individuals, their competition from which autonomy derived its justification, was beneficial to society in unharnessing science and technology. With the victory of technology, indeed with its progress, with men's control over nature, with their independence, their autonomy, autonomy regresses, negates itself. What is under way in the bourgeois era will be completed in the automatized world. As the subject is being realized, it vanishes.

Also, perhaps with an eye to the new generation’s “critical theory in action,” as some of the students called their revolts:

Antinomics of Critical Theory: Today, Critical Theory must deal at least as much with what is justifiably called progress, i.e., technical progress, and with its effect on man and society. Critical Theory denounces the dissolution of spirit and soul, the victory of rationality, without simply negating it.

And in case the implications of these above observations, for critical theory in action, were too abstract, Horkheimer also noted:

In our time, the attack against capitalism must incorporate reflection about the danger of totalitarianism in a two-fold sense. It must be just as conscious of a sudden turn of left-radical opposition into terrorist totalitarianism as of the tendency toward fascism in capitalist states. This was not a relevant consideration in Marx's and Engel's day. Serious resistance against social injustice nowadays necessarily includes the preservation of the liberal traits of the bourgeois order. They must not disappear but be extended to all. Otherwise, transition to so-called communism is no better than fascism but its version in industrially backward nations, the rapid catching up with automatized conditions.

So, even from the comfortable rocking chair of retirement, it seems that Horkheimer’s cultural Marxism was more than a little reticent about the nature of this newly emergent managerial wokeism which was in the process of being birthed by the student radicals. For Adorno, though, the perspective was much less abstract. He was still teaching, and when he refused to provide the blanket endorsement which they demanded of him, the students eventually turned against Adorno himself. He was condemned as an agent of the old regime; his classes and speaking engagements were occupied and disrupted; and in one famous incident which apparently greatly disturbed him several female students surrounded him and bared their naked breasts to him in a class. (Does this all sound vaguely familiar?)

The breaking point for many came on one occasion when Adorno called the police to have protesters removed from the offices of the Frankfurt research institute. This last straw initiated an exchange of letters between Adorno and Marcuse, the latter who of course was solidly behind the students. Let’s conclude these reminiscences with a couple passages from Adorno’s contribution to those correspondences:

5 May 1969

To put it bluntly: I think that you are deluding yourself in being unable to go on without participating in the student stunts, because of what is occurring in Vietnam or Biafra. If that really is your reaction, then you should not only protest against the horror of napalm bombs but also against the unspeakable Chinese-style tortures that the Vietcong carry out permanently. If you do not take that on board too, then the protest against the Americans takes on an ideological character…

You object to Jürgen’s [Habermas] expression ‘left fascism’, calling it a contradictio in adjecto. But you are a dialectician, aren’t you? As if such contradictions did not exist—might not a movement, by the force of its immanent antinomies, transform itself into its opposite? I do not doubt for a moment that the student movement in its current form is heading towards that technocratization of the university that it claims it wants to prevent, indeed quite directly. And it also seems to me just as unquestionable that modes of behaviour such as those that I had to witness, and whose description I will spare both you and me, really display something of that thoughtless violence that once belonged to fascism.

19 June 1969

Firstly, inasmuch as it inflames an undiminished fascist potential in Germany, without even caring about it. Secondly, insofar as it breeds in itself tendencies which— and here too we must differ—directly converge with fascism. I name as symptomatic of this the technique of calling for a discussion, only to then make one impossible; the barbaric inhumanity of a mode of behaviour that is regressive and even confuses regression with revolution; the blind primacy of action; the formalism which is indifferent to the content and shape of that against which one revolts, namely our theory. Here in Frankfurt, and certainly in Berlin as well, the word ‘professor’ is used condescendingly to dismiss people, or as they so nicely put it ‘to put them down’, just as the Nazis used the word Jew in their day. I no longer regard the total complex of what has confronted me permanently over the past two months as an agglomeration of a few incidents. To re-use a word that made us both smile in days gone by, the whole forms a syndrome. Dialectics means, amongst other things, that ends are not indifferent to means; what is going on here drastically demonstrates, right down to the smallest details, such as the bureaucratic clinging to agendas, ‘binding decisions’, countless committees and suchlike, the features of just such a technocratization that they claim they want to oppose, and which we actually oppose. I take much more seriously than you the danger of the student movement flipping over into fascism.

So, again, as with Horkheimer, we find that amid the birth pangs of managerial wokeism, the Frankfurt School’s cultural Marxism, far from enabling or promoting the emergence of this new technocracy was insistently warning about the dangerous path upon which it was travelling. So, also again, while certainly Marcuse was an enabler and promoter of nascent wokeism, to paint cultural Marxism – providing one has any historical understanding of the meaning of that phrase – with culpability in the affair is empirically groundless. Despite his personal trials at this time, Adorno had the clarity to recognize the 60s student movement as a harbinger of a newly hegemonic managerial class that, far from rebuking, entailed the reification and institutionalization of bureaucratic rationality, with its social engineering. Furthermore, Adorno recognized that rather than an opposition to, this nascent managerial regime was better understood as a facsimile of, fascism.

Alas, during this correspondence with Marcuse, Adorno was in very bad health, and indeed their exchange was cut short by Adorno’s death on August 6 of that year. The story has it that Marcuse received Adorno’s final contribution to the exchange on that very day that Adorno died. While not the cause of his illness, it is widely believed his condition was almost certainly aggravated by the students’ constant hounding and harassing of him, which led him to seek refuge for a brief stay in Switzerland, where his heart finally gave out following an ill-advised cable car trip.

So, perhaps Horkheimer wasn’t entirely wrong. At least in effect, the rise of wokeism may have indeed had something of Oedipal patricide to it. In any event, that strikes me as a metaphor more telling than one of nurturing parent for properly characterizing the relationship between managerial wokeism and cultural Marxism.

Parenthetically: of course, a useful method for distinguishing between the validity of competing theoretical models is to measure them against each other in their ability to explain empirical data from the wild. As I’ve been composing this post the world has been atwitter with news of the Colorado supreme court, in a 4-3 vote, removing Donald Trump from the state’s ballots. Predictably I’ve been hearing all manner of condemnation of this as typical “communism.” This is what communists do, and of course, Democrats really are just communists. Obviously this kind of overreaction is low hanging fruit, so I almost feel apologetic for pointing it out, but the point is worth making. If this is standard communist practice and Democrats = communists, why was the vote 4-3? All seven of the justices were Democrats, so according to this theory they were all communists. So why didn’t all the Democrats do what communists are expected to do? This is obviously nonsense. I’d advance instead a class analysis of this situation, focusing upon the dynamics of the managerial class, with due attention to its internal conflicts and dynamics, as I discussed in my book, The Managerial Class on Trial. Through that lens the valuable bit of information is that the three dissenting justices got their law degrees from the law school at Denver University, while the four that ruled to remove Trump from the ballets got their law degrees from Ivy League universities. That tells you everything you need to know about what was happening in that intra-court conflict and indeed what lies behind managerial class responses to the current populist uprising.

We can say with confidence that Marxism failed precisely because Marx gave us precise conditions for the success of his analytical model. Managerial wokeism provides no precision in the description of process to the idealized goals. There’s no final dialectic of transcendence, but only an endless struggle session. The point isn’t to agree, or disagree, with either of these, but to emphasize that they are not the same thing.

Source: The Circulation of Elites

Comments

Post a Comment