The Great German Farmer Protests Have Begun

The Great German Farmer Protests Have Begun

First came the farmers’ protests in the Netherlands, then the Freedom Convoy in Canada. Now the farm protests have reached Germany.

The background is simple: On 15 November 2023, the Federal Constitutional Court declared the budgetary manipulations of the Scholz government unconstitutional, in one stroke depriving our rulers of 60 billion Euros for their doubtful Green projects. It was one crisis too many for the coalition, and in the end it may be the undoing of them. Desperate to save money anywhere, they announced in December their plans to abolish subsidies for agricultural diesel and impose the standard motor tax on previously exempt farm vehicles like tractors, provoking an immediate outcry among the people who produce our food.1 Farmers organised various protests before Christmas, including large demonstrations in Freiburg and Leipzig. There have been sporadic actions since, including a spontaneous protest last Friday at the dock of a ferry carrying Economics Minister Robert Habeck; the protesters prevented him from disembarking and the press are still whining about it. The farmers promised to return after the holidays for a week-long series of protests and traffic blockades, beginning today and culminating in a massive demonstration next Monday in Berlin.

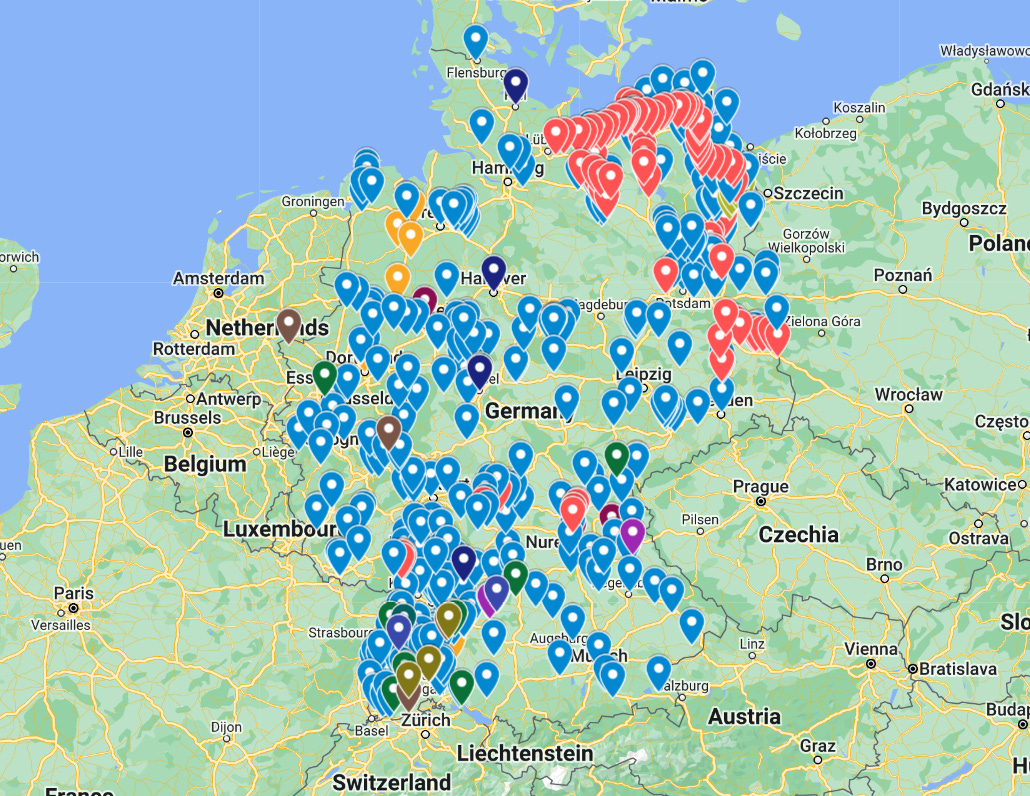

Here is an overview of all the current actions. There are hundreds:

This could not come at a worse time for the people in charge. Scholz and company are already deeply unpopular; the Chancellor can no longer even show up for his own photo-ops without being dogged at every moment by angry detractors. According to the latest polls, the three coalition parties together have the support of only one in three Germans. A mere 34% believe the coalition will survive to the 2025 elections, and 64% want Scholz to resign the chancellorship in favour of Defence Minister Boris Pistorius.

The government, in short, are hanging by a thread and through their own mismanagement they continue to make everything worse. On 4 January, in a clear attempt to forestall the protests, they partly reversed themselves, binning their plans to tax agricultural vehicles entirely and announced that the diesel subsidies would be phased out in stages rather than all at once. At this point, though, it is like trying to force toothpaste back in a tube. Once an uprising has begun, concessions become nothing but an encouragement to protest even harder, especially when the immediate provocation itself was nothing but a symbol for much deeper and more widespread dissatisfaction:

[Brandenburg farmer] Harmut Noppe … feels betrayed by the austerity policy of the coalition. On the farm he founded shortly after reunification, the 62-year-old – together with six employees – grows various types of grain and oil seeds. … A total of 20 heavy agricultural machines are used in the daily work on the farm … The abolition of the agricultural diesel subsidy would result in considerable costs for the farmer.

Noppe explains [that] a farmer currently receives back from the government around 20 to 25 euros per hectare of cultivated land. If the payments were to be cancelled soon as planned, the average farm in the state of Brandenburg would incur additional costs of around 5,000 Euros per year. According to the state farmers’ association, the cuts could total more than 20 million Euros.

Most farmers are unable to pass on the increased costs to consumers, Noppe explains. Grain prices, for example, are often set by wholesalers … “There will certainly be farms for which the business is no longer profitable,” he surmises. It cannot be ruled out that some farmers could give up their businesses completely in the face of further restrictions.

Another problem is that the current federal government simply lacks expertise. “The government's decisions should be made on the basis of professional considerations,” Noppe says. “What the government are doing right now is pure ideology. They don’t know what they're talking about.” …

“The coalition are making policy for the urban population,” says Noppe. “They are not interested in rural areas. The population here is being completely left behind.” Instead of looking for solutions together, they continue to govern from the top down. This leads to disenchantment with politics – especially in rural areas, Noppe observes. “The people here agree that things can't go on like this.”

That’s from the Berliner Zeitung, which is often distinguished by its independent and thoughtful reporting. The same cannot be said of the rest of the German press, which has reacted with unhinged hysteria. Professional shithead Arno Frank, in a widely circulated piece for Der Spiegel, has denounced the protesters as a “motorised pitchfork mob” and “profiteers of the agricultural lobby”:

The farmer is an almost mystical figure, because he does not usually sit in the Bundestag, in important law firms or editorial offices. Unlike train drivers or doctors, farmers do not go on strike. They “take” their protest “to the streets” and literally spill their dung there like other people spill their hearts out. Then they – and everybody else - remembers how intimidating paramilitary vehicles like combine harvesters can be when they when they travel in convoys on the motorway or fogs up city centres with subsidised agricultural diesel …

[A] whiff of anarchy and revolt wafts through the land when the farmer gets really angry. It is as if there is a shadow army just waiting for the command to strike – even if it is only to prevent the private Robert Habeck from leaving a ferry …

Convincing the farmer, as a traditional keeper of the tried and tested, of the need for progressive change is no easy task. … What we will see over the next few days is the escalation of a communication problem. Problems are solved in meeting rooms, not on ferry docks or in marketplaces.

If you asked me to compose a parody Spiegel editorial denouncing the farmers from the perspective of a sheltered urban journalist who is personally terrified of tractors and harbours unusual fantasies about the violent tendencies of those who grow his vegetables, I doubt I could have done any better than this. It goes without saying, of course, that Frank does not have a problem with protesters in general, so long as they are the right kind. As recently as September he penned “The Supergluer,” a long and quite nauseating profile of the “thought leader” and lead Letzte Generation activist Lea Bonasera.

The dominant theme of press coverage is that the protests will be instrumentalised, perhaps even hijacked, by that legendary ideological beast known as “the extreme right.” This view is especially prevalent in state media. Thus, of many possible examples, NDR have brought in a “conflict researcher” named Felix Anderl to express his concern “that society and therefore also the farming community are experiencing a shift to the right,” tagesschau ask whether “the farmer protests are being hijacked by the right,” and RND report more decisively about “how right-wing extremists aim to hijack the farmers’ demonstrations.” Government politicians have adopted much the same line, with Robert Habeck, fresh from his ferry kerfuffle, claiming that “far-right parties such as the AfD are … clearly trying to instrumentalise farmers”; and our constitutional protectors warning that the protests will be infiltrated by extremists. As I type this, journalists are thick on the ground, eagerly reporting every last sighting of “extreme right-wing groups” at protests in Dresden, Cottbus, Munich and elsewhere.

Unfortunately, the farmers have reacted poorly to this framing. Joachim Rukwied, president of a Farmers’ Association in Baden-Württemburg, made headlines yesterday by screeching to Bild that “We don’t want any right-wing and other radical groups with revolutionary fantasies at our demos! We are democrats and political change takes place, if at all, through voting at the ballot box.” Other organisers have aired similar views on social media, apparently failing to recognise that all it takes to qualify as a right-wing extremist is dissatisfaction with the present political order of the Federal Republic, and that even the most right-thinking centrists among the protesters will be classified as unhinged fascists if they see any success at all.

In modern liberal politics, the protest is the subject of an entire mythology. You could almost say that it is a sacred ritual, as central to the performance of democracy as masking is to the performance of virus hygiene. In this mythology, protesters take to the streets to demand things like justice and change, and politicians hear their grievances and condescend to address them. In truth, we are treated to a great wealth of approved pseudo-protests, where the activists merely demand things that establishment politicians are already doing or hope to do soon. Our states and their journalist collaborators are deeply hostile to real, spontaneous activism against their policies; we saw this during Covid and in the coming week we will see it again.

As always, I think it’s important to moderate one’s expectations. Contrary to the mythology, protests by themselves generally aren’t mechanisms of political change, but real protests can be important barometers of popular sentiment, and they are one more problem that the German government must spend energy and resources to mitigate. The only thing that made the Green policies of the coalition minimally tolerable was the nearly unlimited spending capacity they inherited from the fake Covid emergency. Now that they don’t have that money, they find themselves widely despised beyond the upper middle-class urban ideologues whom they represent. And that is not nearly enough to govern.

The tax exemptions for agricultural vehicles stem largely from the fact that they are not used primarily on public roadways; the same is true for the diesel “subsidies,” which are not really subsidies at all but exemptions from ordinary tax on diesel.

Source: Eugyppius - A Plague Chronicle

Comments

Post a Comment