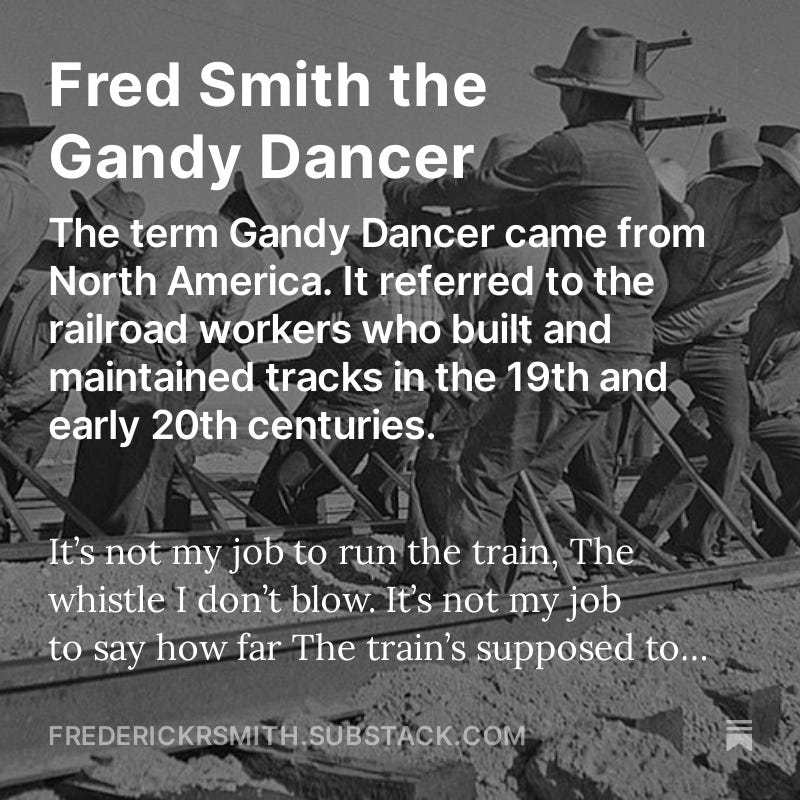

Fred Smith the Gandy Dancer

Fred Smith the Gandy Dancer

The term Gandy Dancer came from North America. It referred to the railroad workers who built and maintained tracks in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

It’s not my job to run the train,

The whistle I don’t blow.

It’s not my job to say how far

The train’s supposed to go.

I’m not allowed to pull the brake,

Or even ring the bell.

But let the damn thing leave the track

And see who catches hell

A poem of unknown origin ~ best describes Fred Smith’s relationship to the track his entire career

Foreword

Paradoxically, the journey back to understanding the past opens a new door to discovery. That is true even for individuals such as myself who have journeyed through life in a profession rich in history. With that in mind, the goal is to bring you something unique and enjoyable, a respite from today’s overarching and revolting realities. I hope you enjoy another trip back in time as we travel “Along the Iron Road.”

Background

The term Gandy Dancer came from North America. It refers to the railroad workers who built and maintained tracks in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The job was demanding. It required copious physical effort and coordination among the workers to ensure the tracks were aligned correctly. The term Gandy Dancer likely came from the workers’ rhythmic movements and chants, which they used to coordinate their efforts. The flat-footed steps resembling geese walking may have also influenced it. Nevertheless, there has yet to be an agreement on its exact origin.

Gandy dancing involved lifting rails and shifting tracks, driving spikes into ties with spike mauls, and tamping ballast. Each crew member had a specific role, which showed that teamwork and coordination are essential. Fast track laying and maintenance demanded their unflinching toils. The crew often used rhythmic movements, chants, or songs. These activities synchronized their efforts and built camaraderie during long workdays.

Gandys used many tools, including claw bars, picks, and shovels. They also used sledgehammers, chisels, track wrenches, drift pins, tie tongs, spike mauls, track jacks, and “rail dogs.”1 These were essential for lifting rails, digging tie holes (cribbing), and adjusting track alignment. The working conditions were challenging, including extreme weather and long hours. Yet, many workers took pride in their contributions. They helped to build and maintain the vital railroad infrastructure, which was crucial for North America’s economic development.

Technology and changes in the railroad industry reduced the role of the Gandy Dancer in the mid-20th Century. Machines replaced much of the manual labor performed by Gandy Dancers to throw track. But as we shall see, many skills live on with the modern Gandy Dancer.

The Iron Road Journey

Gandy Dancer refers to railroad wayside workers. They tirelessly laid and maintained tracks before machines took over much of the work. Officially known as “section hands,” these individuals formed the backbone of railway infrastructure. Their work was grueling, and their harmonic efforts were vital. They were critical to the railroads’ function.

In your mind’s eye, look to a crew of Gandy Dancers, tools in hand, moving in unison, led by a caller or call man orchestrating their movements. As they repaired tracks, they lunged against their tools, nudging the rails into alignment. They coordinated their efforts like a dance that ensured the trains ran smoothly. The Gandy Dancers wielded many specialized tools. The most notable was the lining bar (Gandy), a five-foot-long steel lever used for track alignment.

Nevertheless, the origin of the term Gandy Dancer remains speculative. Some suggest an Irish or Gaelic influence due to the rhythmic motion resembling traditional Irish dances. Another theory points to the Gandy Manufacturing Company of Chicago or the Gandy Shovel Company. They made tools used by the Gandy Dancers. However, the company remains elusive, akin to a legend passed down through time. Some writers have suggested that “Gandy” may be a corrupted form of “gander.” This is from the nodding of the workers using the tool. It implies that the Gandy Dancer who used it gave it its name. The first recorded use of the term Gandy Dancer occurred in 1918 with Volume 119 of the weekly magazine “Outlook.”

What is a “gandy dancer”? The words were on a blackboard outside a store on the Bowery. In old times, they might have suggested the proximity of a cheap dance house. But the Bowery has changed. Within the space of a few blocks, there are now more than a score of “labor bureaus” where formerly were low dives and “suicide halls.” Inquiry of an Italian employee of the bureau elicited the information that a “gandy dancer” is a railway worker who tamps down the earth between the ties, or otherwise “dances” on the track. The announcement read:

Men wanted for track work cinder ballast no rock straight time rain or shine paid weekly accommodation very good Board furnished $5 per week It is a good job particularly for veteran gandy dancers It’s a few miles out and requires no weeks toil to get back to this burg. Another bureau’s sign called for “gandy danzers,” a variation of the spelling.2

Since then, it has had various slang meanings, including a petty crook or tramp, an Italian, a jitterbug, a womanizer, or an active socialite. Gandy Dancing influenced popular culture. Thanks go to Speaks reader M.H. for finding this clip:

The Gandy Dancers were unsung heroes, often overlooked in the grand narrative of railroad expansion. Their sweat, rhythm, and determination shaped the iron arteries connecting cities, towns, and dreams. They sang work songs to keep their rhythm. Their chants echoed across the tracks like a hi-fi’s fine frequency modulation (F.M.). The songs kept spirits high and movements synchronized. The tracks became their stage, and the dance of the rails played out under the vast sky.

Each section crew or “gang” maintained 10 to 15 miles of track. They performed tasks like tamping and “dressing” ballast, replacing rotted crossties, and straightening tracks. Straightening the track, known as lining, was a significant aspect of their work. Workmen also would jack up the track at low spots and push ballast underneath while the caller marked time with a four-beat “tamping” song. That involved vigorous stamping on the tool while turning in a circle, an action that resembled dancing.

The foreman of a section crew was traditionally white. The members were predominantly African American, principally in the Southeast. In the West, Hispanics complemented much of the Gandy Dancer workforce. Elsewhere, it was a mix of nationalities. The foreman stood at a distance from the crew. Using his sight focused on the rail alignment, he signaled the caller. Section crews could vary in size, depending on workload. They ranged from four to thirty men. Each worker had a lining bar to nudge the track.

Gandy Dancer Work Song Tradition

Building (laying) and maintaining railroad tracks was challenging and laborious, where the synchronization and timing of the team’s effort outweighed individual strength. African American teams exemplified the Gandy Dance with their wonderful melodic refrain. The caller played a pivotal role in maintaining this synchronization, motivating the workers while setting the pace with rhythmic work songs. They drew inspiration from various sources like sea shanties, cotton-chopping tunes, blues, and African American spirituals. These songs typically followed a two-line, four-beat pattern. As the crew members tapped their lining bars against the rails, the rhythmic chants echoed the pulse of their collective labor.

The Dancers tapped in flawless unison. In one of many renditions, the caller would signal for a vigorous pull on the third beat of a four-beat refrain. The rhythmic four-beat sequence persisted until the foreman signaled the track was correctly aligned. A skilled caller could maintain a continuous stream of unique phrases throughout the day. Experienced section crews, when observed by onlookers, frequently added flair to their work by incorporating one-handed gestures and stepping out with one foot on beats four, one, and two. They executed two-armed pulls on the lining bars on beat three.

Back to the Future

The mechanization of railway trackwork has been a gradual process spanning a century. Initially, manual labor was the primary method for laying tracks, maintaining infrastructure, and conducting repairs. However, as railways expanded and traffic volumes increased, a need arose for more efficient and cost-effective methods.

The introduction of steam-powered machinery in the 19th Century marked the beginning of mechanization in trackwork. Steam cranes, track-laying machines, and ballast tampers were among the early innovations that helped speed up construction and maintenance processes. These machines reduced reliance on manual labor and significantly increased productivity.

Below is fantastic footage from the 1906-1914 timeframe. Note the lack of spiking ahead of the machine. At 3:42, look closely, and you can see a gage rod being installed to hold the rail spacing so the machine can advance. Later, the footage shows spiking occurring to the rear of the rig. Based on the markings on one car, this footage is from the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

In the 20th Century, diesel and electric-powered equipment further revolutionized trackwork mechanization. Hydraulic and pneumatic systems were integrated into track-laying machines, allowing for more precise and controlled operations. Below is a documentary film from 1973 (one year before I started my professional journey):

…. 16mm film by Jack Schrader and Tom Burton that features field recordings of work chants of Gandy Dancers including aligning songs and chants to knock out slack in the rail. Shot with a 16mm Bolex camera without sync sound, the visual shows men working with cross ties, aligning the track, and spiking. The film focuses on the changes brought about by mechanization of railroad building. The film is part of the Burton Schrader collection in East Tennessee State University, Archives of Appalachia.

The advent of computerized control systems in the late 20th Century brought about further advancements, enabling the automation of track maintenance equipment.

Even with these advancements, many craftwork elements of the Gandy Dancer tradition continue. Some examples of the modern Gandy in action today include:

Inspector making spot repairs during a track safety patrol

Emergency repairs

Spot repair of a track defect that occurs in between scheduled mechanized renewals

Attaching a newly machine-laid rail to an existing track

Special trackwork (switches and rail-to-rail crossings) and highway-rail grade crossings. To this day, these types of structures demand skilled manual labor.

Many short-line and industrial railroads lack the luxury of large-scale track production machines. Thus, much of the Gandy Dancer craft lives on. For example, while a large crew of Dancers may never be employed to “throw track,” a foreman with a sharp eye and a skilled backhoe operator can do wonders. From experience as a foreman with that “eagle eye,” it was a rewarding experience to signal the backhoe operator to make a track alignment uniform with the nudge of his excavating bucket.

Meanwhile, “windmill spiking” or “roll spiking” with a spike maul was good for my muscle-building and honing of synchronization skills.3 We knew it was a good drive when the mark on the top of the spike was like a shiny dime. Marks and nicks meant you needed practice to get it right.

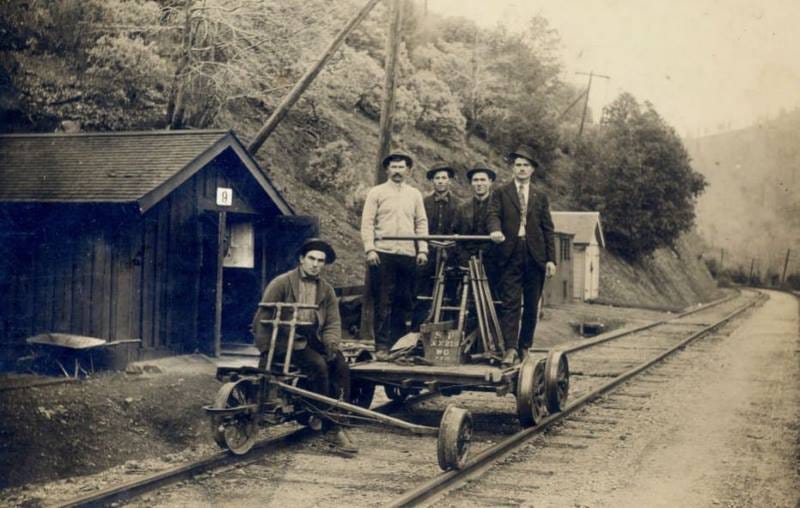

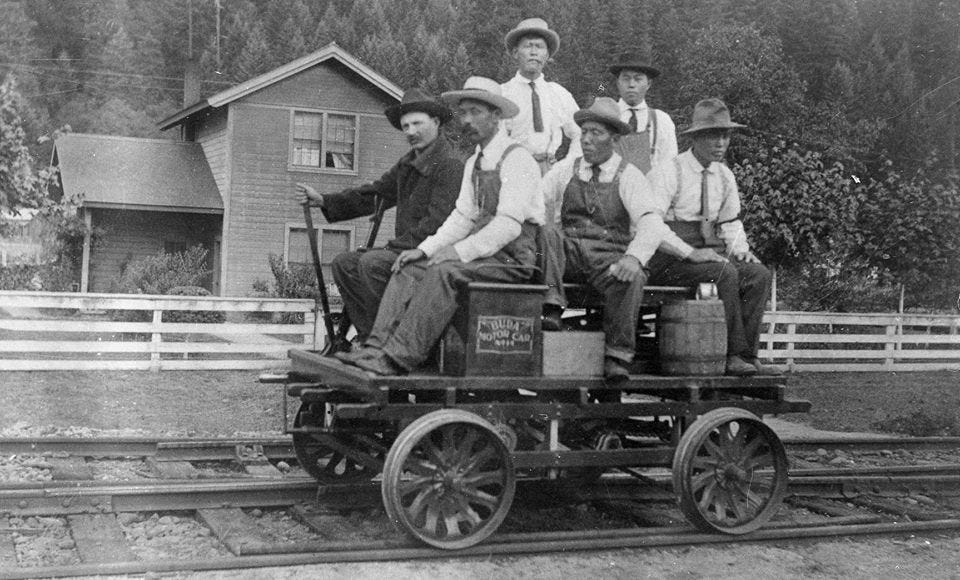

Traditionally, Gandy Dancer crews moved about in specially built lightweight track cars. In the early years, they were man-powered, using hand or pump cars and velocipedes.

Steam locomotes ruled the road until the 1940s. However, maintenance of way forces embraced the invention of the internal combustion engine at the beginning of the 20th Century, with track cars powered by small engines. These contrivances helped the teams move along the sections for which they were responsible.

Despite the introduction of modern methods, some railroads, such as the White Pass & Yukon Railway (WP&Y), continue using legacy roadway worker transportation machines. Called “rail car,” “motor car,” “track car,” or “speeder,” these devices provide a reliable instrument to inspect and maintain tracks and bridges in remote areas. Ironically, in 1974, the first year of my storied railway career, a short-line railroad motor car provided my transportation to work sites. That work entailed using hand tools used by the great Gandy Dancers of the past.

Today, crews mostly use custom-designed vehicles, known as hi-rail vehicles. These vehicles can traverse the highway and train tracks for flexibility and ensure efficient maintenance.

Conclusion

The term Gandy Dancer is no longer used in the railroad industry. Yet, it remains a big part of North American railroad history. It represents the hard work and friendship of the men who built and kept the tracks that connected communities and drove economic growth. The Gandy Dancers were a vital part of early American railroad history. They were famous for their synchronized movements of a crew working in unison and the rhythmic clinking of steel against steel. Their work was essential for laying and maintaining tracks. It ensured safe and smooth train journeys across the vast United States.

The term Gandy Dancer evokes a bygone era—a time when manual labor and collective effort built the backbone of transportation. So, the next time you hear a distant train whistle, remember the Gandy Dancers—their dance lives on in the heartbeat of the rails.

The vital Gandy Dancers epitomized resilience and teamwork. They expanded and maintained the railroad network that shaped North America. Regardless of their origins, the Gandy Dancers of today traverse the railway lines for inspections. Each train’s passage causes vibrations that can loosen track fixtures. That underscores the need to tighten bolts, inspect for damaged ties, and remove obstacles like fallen trees.

As we approach the final stop of this essay in the ongoing series “Along the Iron Road,” enjoy another musical rendition of the Gandy Dancer.

Without a doubt, Speakes readers now fully grasp the term Gandy Gancer more than the great musicians and singers who popularized it. Perhaps the same can be said of the patrons (except as noted below) and owners of the beautiful Gandy Dancer restaurant in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Many thanks go to Speaks reader Fr. G.H., who told me about the Gandy Dancer restaurant during the research associated with this essay. He had a meal or two at the former train station, now a towering eatery.

Bonus!

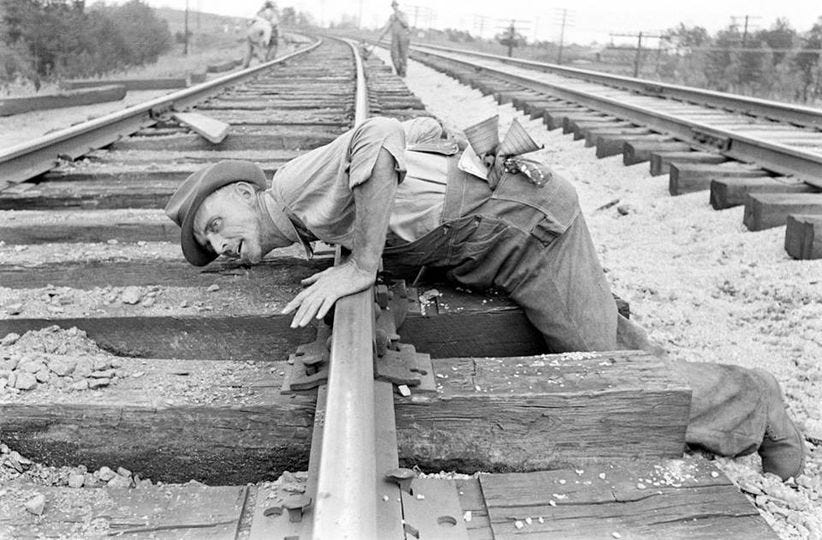

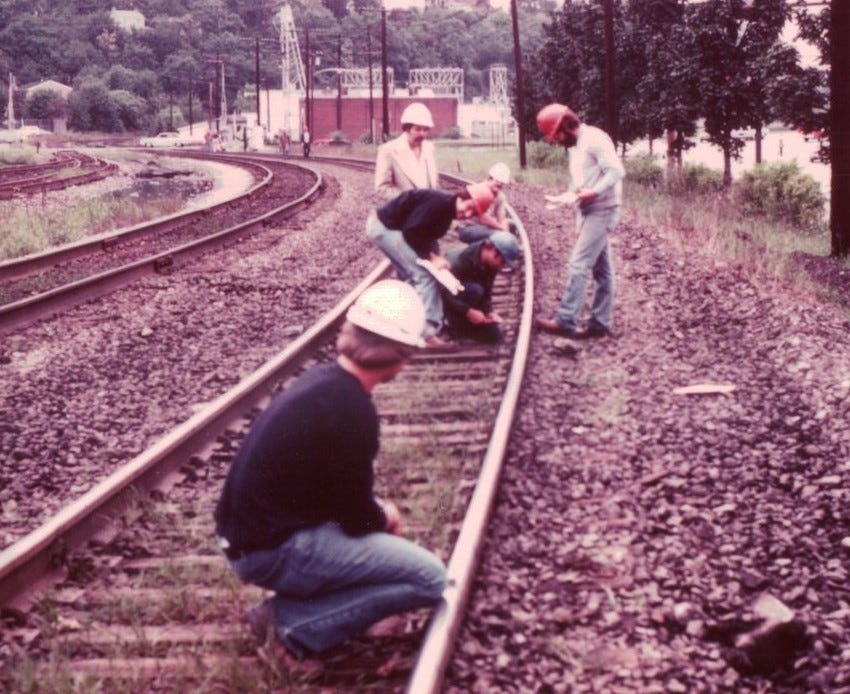

For more of “Fred’s Boots on the Ground,” yours truly snapped the photo below while enrolled in a major freight railroad’s “Track Foreman Training Program” in 1977, a few years into my career. We young chaps were enjoying a mathematical field exercise called “stringlining.”

Today, few railroad employees know the delicate skill of stringlining to determine the existing alignment of a curve and calculate a new smooth path using the “Bartlett” or “Bracket” methods. The resulting station calculations every 31 feet would be used to “throw” curves (minus or plus) with jacks. Modern production machines make short work of this task with a computer-calculated “graph” to make it happen with a new type of dance.

Now, for real fun, ride in a makeshift hi-rail from the motion picture The Flim Flam Man.

Parting Handshake

There was a 2013 “somebody has to do this” day in Virginia, with five years to go until retirement. It had been many decades since I handled those Gandy tools. 📕

Sources

Online

Gandy Dancer Work Song Tradition ~ Encyclopedia of Alabama

Calling Track and Military Cadence Calls: How an African American Tradition Influenced Military Basic Training ~ Keepers of Tradition

Gandy Dancers ~ Folkstreams 1994

Gandy Dancer: Definition, Railroads, History ~ American-Rails

Frederick R. Smith R. Smith Library

Dictionary of Railway Track Terms ~ Christopher F. Schulte, 248 pages, Simmons Boardman Books Inc., May 2012

A Treasury of Railroad Folklore ~ Edited by B. A. Botkin and Alvin F. Hartlow, 530 pages, Bonanza Books, 1953

Railway Engineering and Maintenace Cyclopedia, Simmons-Boardman Publishing Co., 1972 pages, 1926

Rail dog is slang for rail tongs, a tool for lifting a rail by two men side by side.

Some railroads prohibit dual spiking due to past injuries occurring from this practice.

Source: Frederick R. Smith Speaks

Comments

Post a Comment