Strangled In The Dark For A Good Harvest?

Strangled In The Dark For A Good Harvest?

Using modern forensics to solve a Neolithic ritual murder

At the Middle Neolithic site of Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux in the central Rhône Valley, one of the most disturbing burials of European prehistory has come to light. The reconstruction of the scene is almost a work of art, relying on the most meticulous and patient observations, and the payoff is immense. The resulting paper covers the evolution of a ritual murder charmlessly dubbed ‘homicidal ligature strangulation’. 20 cases of this particular death have now been identified, starting in Sicily at the end of the Italian Mesolithic, and concluding around 3,500 BC in the Rhône valley. Using modern forensic techniques, archaeologists are dispelling the idea that the Neolithic was in any way a peaceful time to live, and are unearthing some of the most unsettling rites of Europe’s stone age farmers.

Solstices, silos and strangulation

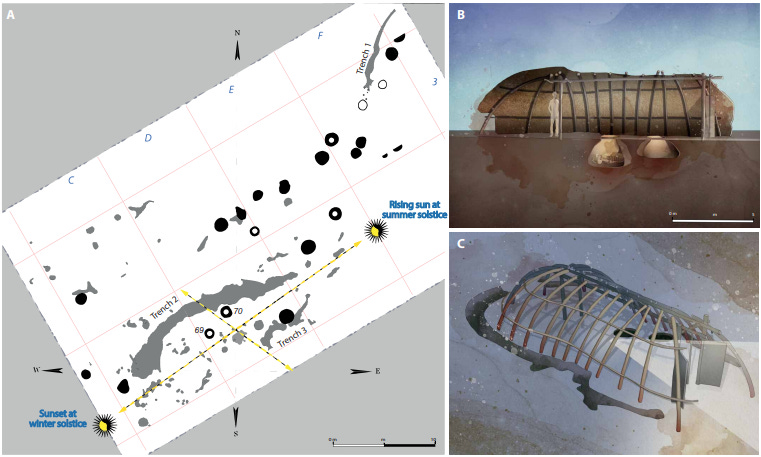

Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux is one of many large open-air sites in south east France belonging to the Chassean complex (4,300 -3,600 BC). Researchers have built detailed models of how these farmer-herders used the landscape thanks to their habit of adopting natural caves and rock shelters as animal pens for parts of the year. Plant bedding, goat and sheep dung, even juvenile milk teeth are all in abundance in these caves, and working out how young and mature animals were rotated, bred and slaughtered across Chassean sites has been highly fruitful. The remainder of the economy was based on growing millet, rye, fruits and keeping cattle and pigs. At Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux, as elsewhere, numerous underground pits and silos have been found. Some contain mundane ordinary objects - food stores, pottery, flint tools - while others contain human and dog burials, broken grindstones, foreign ceramics and unusual stone or pebble infills.

Broken grindstones are a worth a mention here. The longevity and durability of grindstones often gifts these heavy artefacts a more mysterious quality than the average domestic tool. They are instrumental in converting inedible grain (wild, nature) into edible flour (domestic, culture), and are handed down from generation to generation. Broken grindstones in a pit together with several dogs and imported pottery speaks of something more than ordinary household disposal. If we imagine these stones as later cultures did with swords, as having an animistic lifeforce perhaps, then deliberately breaking one or burying fragments of old and worn out stones was likely wrapped up in their agro-religious worldview.

Two silos in particular though stood out to the excavators of the site. They were enveloped in the remains of an oval shaped building or structure, one with two entrances, perfectly aligned to the solstice suns: sunrise in midsummer, sunset in midwinter. That one of the two pits contained the bodies of three women seemed to confirm that the whole ensemble was ritualistic in nature.

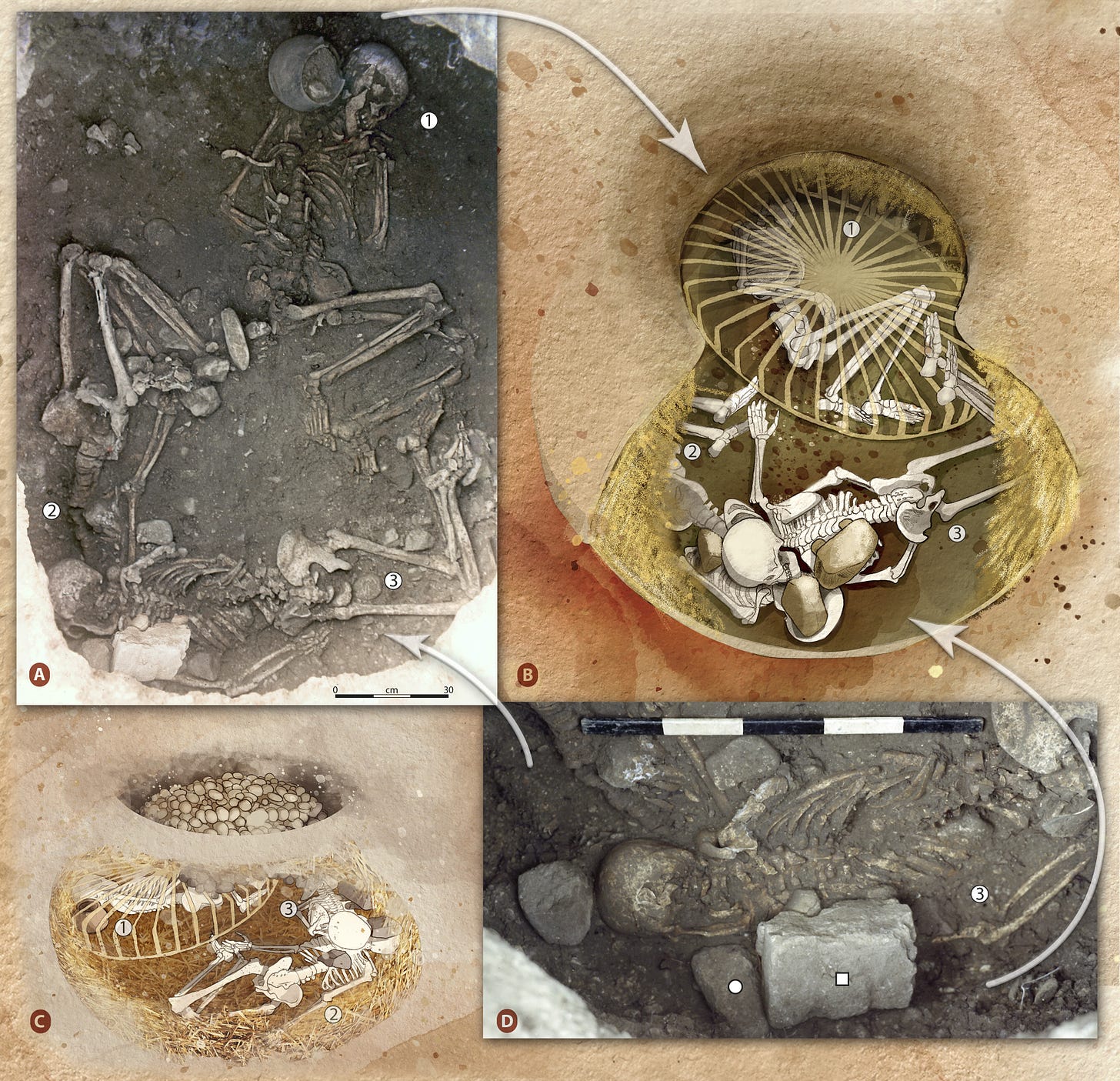

Typically storage pits in this culture contained seeds, and a layer of burnt charcoal along the bottom, interpreted as a practical way to sanitise, remove insects and rodents and reduce moisture. This particular storage pit with the three bodies did not have these features, but was instead lined with straw, leading the excavators to conclude that it was a grave deliberately shaped as a food storage pit. Describing the positions of the three individuals is surprisingly difficult, but we have this arrangement:

In the centre of the pit an older woman (50+ years) was placed on her back, her legs and head leaning left, a large ceramic vessel next to her head

Along the edges of the pit, under the overhang, are two strangely positioned bodies. One of them is lying on her back, with her legs bent back behind her. She had pieces of grindstone placed on her head.

The third woman was laid on her stomach, her neck over the thorax of the second woman. She had grindstone pieces placed over her back and head as well.

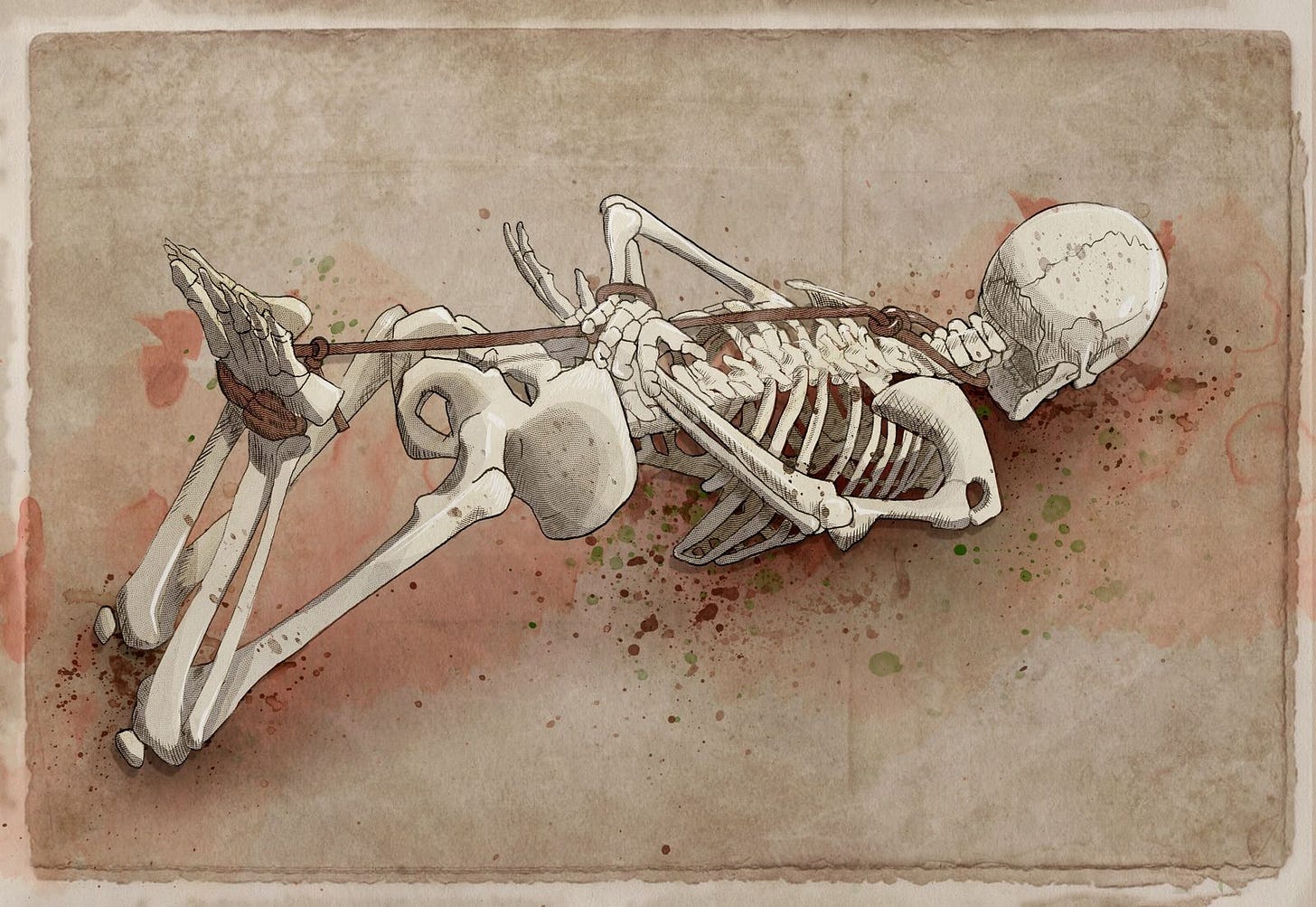

The unnatural contortion of the second woman led researchers to conclude that her ankles had been bound, and then a cord or ligature tied from her feet over her back and around her neck - trussed up so that when her feet dropped she was cutting off her oxygen. Modern forensic reconstructions of murder scenes use a number of methods to work backwards from the placements of the bones to the body just after it died. This involves detailed knowledge of how bodies decompose and how bones move as the internal body cavity collapses while tissue decays. Within archaeology this is known as archaeothanatology, and can help researchers reconstruct mortuary rites such as whether a corpse was bound, dressed, left in the open and so on.

Applied to this burial pit, archaeothanatology fills in the blanks to reveal a thoroughly shocking scene. Given the estimated volume of the women’s chest cavities, the placement of the grindstones and overhang of the pit - these two women were squashed, or wedged into position while still alive, with their heads and chests pinned on top of one another under the tiny overhang space. The woman on the bottom was likely tied up as mentioned. Its hard to imagine a more terrifying death, suffocating on top of one another, crushed together in that tiny pitch-black void. The woman on the bottom would have died more quickly, but the researchers speculate that the upper woman would have laid out on her unfortunate companions chest and over time succumbed to either asphyxiation or more likely a heart attack. Given the circumstances, with the older woman in central position, and the two younger woman out of sight at the edge of the pit, its reasonable to conclude that this was a sacrifice of sorts. A specially commissioned pit mimicking a storage well, a structure aligned with the solstices, an older woman… the whole affair is charged with a particularly gruesome agricultural magic.

Tracking A Ritual Murder

While the scene is unpleasant in many ways, what struck the archaeologists here was the way the second woman was trussed up, her legs used to strangle herself. To make sense of this they turned to the forensic literature and discovered that this method of murder-torture is still used today, almost exclusively by the Italian Mafia - a method known as incaprettamento. The motivation is humiliation, to bind up the victim like a goat, and degrade either the living person or the corpse after death to dishonour his memory and family. The literature on the subject is fairly sparse, but most examples are from Italy and sometimes East Timor.

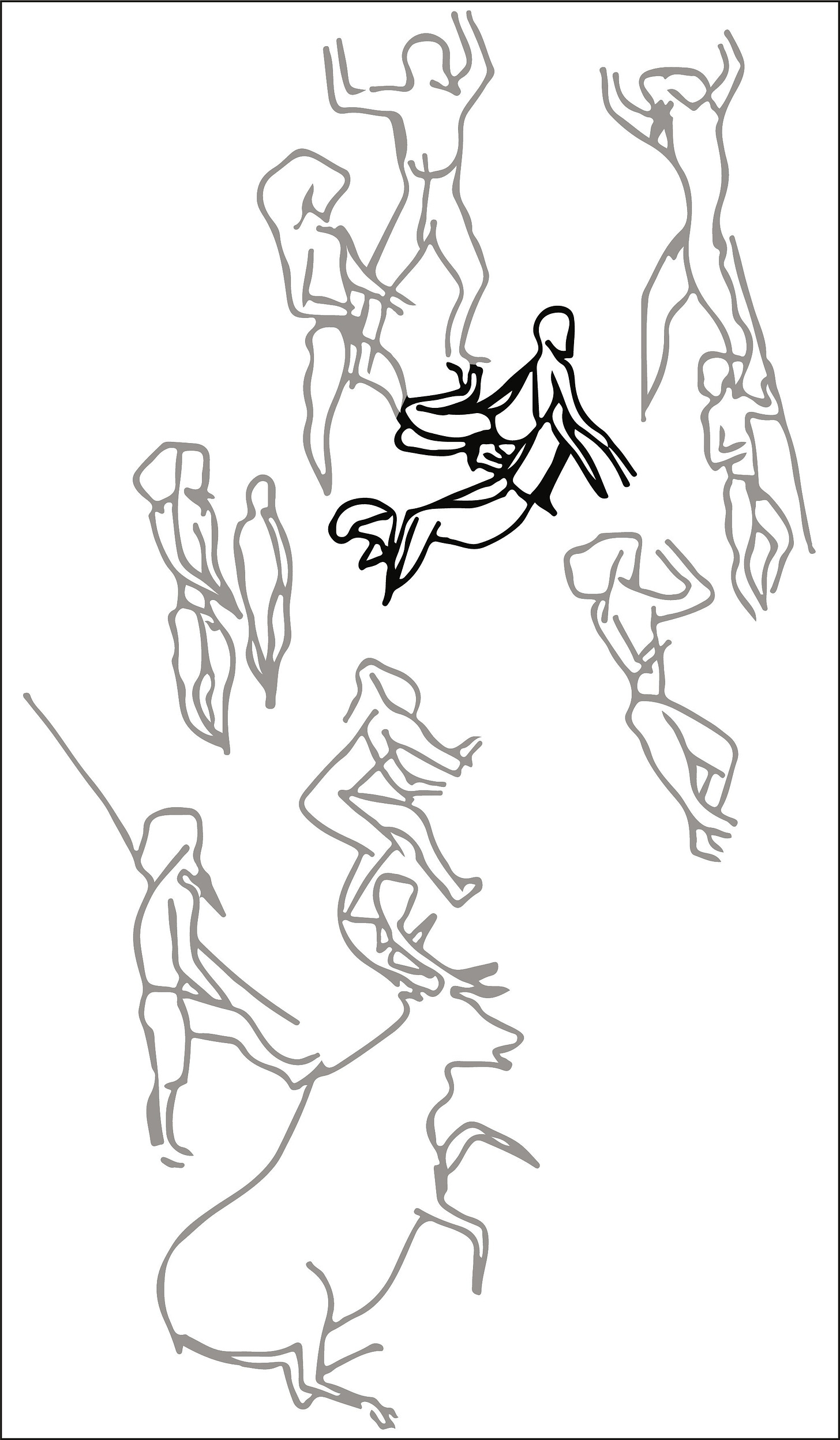

The authors devote the remainder of the paper to tracing the origins of this ritualised form of murder in the Neolithic. Do other examples exist, and if so do they turn up in a specific context? The earliest example appears in… Italy, specifically in Mesolithic Sicily, which doesn’t seem to share any obvious connections to an agricultural village millennia later in France. The evidence from Sicily is not from any skeleton or grave however, rather it comes in the form of a highly unusual piece of cave art, found in Addaura Cave. The image is below and I quote the full description from the paper, which provides several interesting details.

According to J. Guilaine (36), this scene features eleven humans and a deer, which, given its position, is most likely deceased (sacrificed?). Nine of the humans are standing (in gray); several of them are adorned with bird-like beak faces, resembling masks, and they all appear highly animated. The artist aimed to convey a sense of general excitement. They encircle two central humans (highlighted by us in black), in a prone position. They lie on their abdomens with their legs folded beneath them; one has their arms hanging, while the other has them folded behind their neck. There is a rope stretched between their ankles and neck. Male genitalia in the two figures are very clearly depicted, as if erect, and the figure underneath is shown with their tongue hanging out; these two signs are found in cases of strangulation or hanging.

Both the erotic and sadistic elements have been much commented on over the years, and the link between the two is hardly a surprise. Auto-asphyxiation for sexual gratification, spontaneous ejaculation during execution on the gallows, lovers helping to hang one another for pleasure - such things have been known about since the dawn of time, and have featured in folklore and art as far apart as the Classical Maya and Renaissance Italy. I haven’t seen the argument made yet, but the Addauran artwork could depict a voluntary act of self-strangulation, where death, sex and animal sacrifice have mingled into one ceremony.

Outside of this Mesolithic example the other examples identified in the paper are all Neolithic, from a mixture of locations and times. 20 individuals were highlighted as fulfilling the criteria of incaprettamento, breaking down to:

Nine men, seven women, four children

16 tombs across 14 sites

An arc from the Elbe to the Ebre, spanning 5,400 to 3,450 BC

Many also showed similar characteristics to the Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux burials, including the use of silos or commissioned silos, broken grindstones, foreign pottery, buried dogs and cattle and a relationship to the solstice. What is especially curious is the ‘mosaic’ like quality of this ritual’s appearance. It is not confined to one Neolithic culture or another, nor is it clustered around a particular time period. Rather it seems to pop up in different places, separated by great cultural distances which we assume, based on genetics, would have created different languages and religious beliefs. That children below ten years of age would be singled out for this grim sacrifice boggles the modern mind, and is a good reminder that the past is indeed a foreign country, they do things very differently there.

Overall the paper leaves us with more questions than answers, and stirs the imagination in trying to work out what kind of ritual this was - a once in a generation renewal sacrifice? A seasonal gathering of many disparate groups to confirm and solidify ties of blood? Perhaps the victims were selected months or years beforehand, willing participants in their demise? To truss a person up like an animal speaks of a transformation or a transfer of animal-qualities onto that person, they are a sacrificial lamb, no longer a human but an offering. We also get a glimpse into religious practices that are perhaps deeper than immediate culture, but hearken back to some ancient ancestral rite from Anatolia, or an encounter with Europe’s lost Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who demonstrated the necessary rites to keep the land fertile and productive? One thing is for sure, the Neolithic is no longer an endless archaeological summer of peace.

Source: Grey Goose Chronicles

Comments

Post a Comment