Where Do The Children Play?

Where Do The Children Play?

The population bomb, birthrates and the future of humanity

When a writer says that he believes that Western civilization is falling he is called a pessimist. Perhaps he is really an optimist. Was it not well for the world that the vile old civilisation of Rome, built upon a tenement-housed population of slaves, passed away? How otherwise could the virile young nations of Christendom have arisen? When we survey the urban civilisations of our own time, with their shoddy cinematograph amusements to stupefy a mass of wage-slaves, just as the circuses of old stupefied the mobs of Rome – with their worship of wealth, their ugliness and joylessness and disease – are we pessimists if we think that Providence soon will make a clear sweep of the mess, and will makes a way for the unspoilt peoples?

— Aodh De Blácam, Heroic Ireland

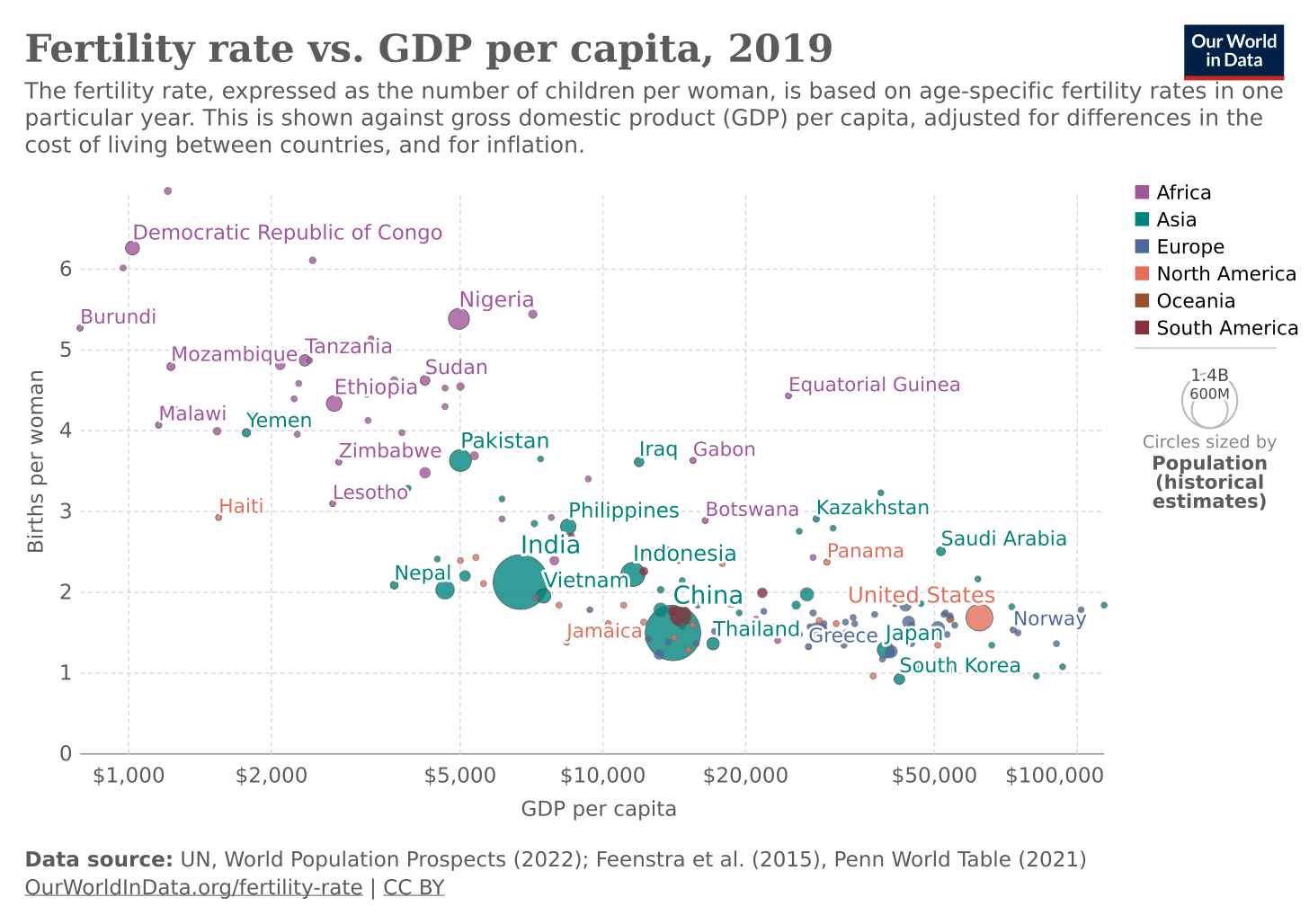

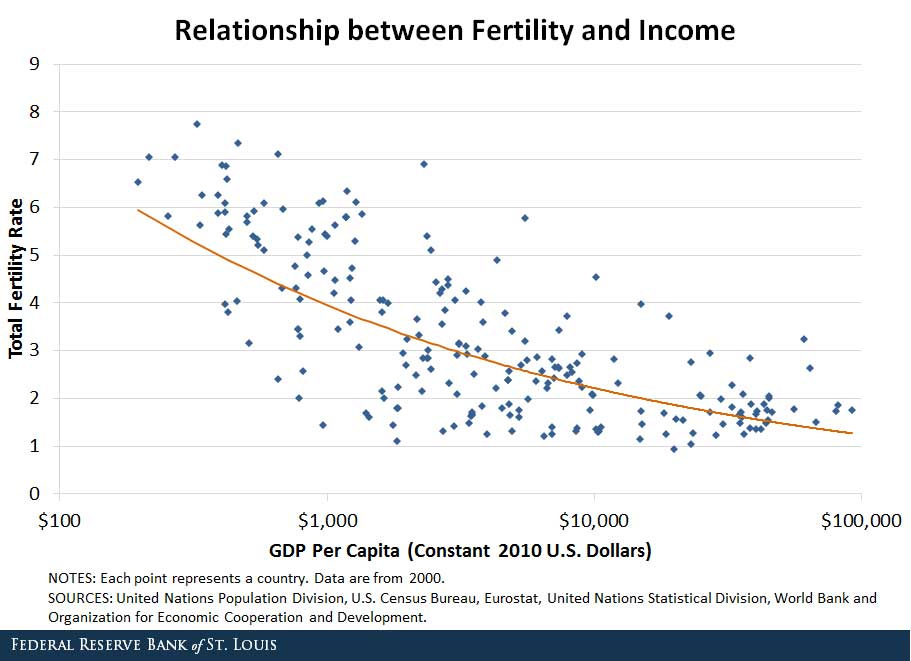

The Economist Philip Pilkington wrote an essay on what he called “Capitalism’s Overlooked Contradiction”. He identified this contradiction as the “tendency of the rate of people to fall.”

Pilkington was here borrowing from Marx, whose prediction of a necessary collapse of capitalism and transition to communism was premised on a fundamental contradiction he believed he had identified in the logic of capitalism: since labour was the source of all value, as capitalists invested in technology the amount of surplus value they could squeeze out of the production process would necessarily fall, leading eventually to a collapse.

Marx’s predictions proved incorrect, but as Pilkington argues, when it comes to population, there does seem to be a contradiction which limits the necessary continuous expansion of a capitalist economy. As per capita GDP increases, the total fertility rate declines, the share of retirees and people reliant on welfare thus increases, in turn lowering economic growth. And so, Pilkington concludes:

Left to its own devices, capitalism’s categorical imperative of work and consumption is, in the end, at odds with its structural needs, as it discourages family formation and thus stymies the capitalist economy’s ability to grow. This is the core contradiction of capitalism—much more profound than anything Marx imagined.

Though nationalists and conservatives are reluctant to attack capitalism as a source of their woes, the tendency Pilkington describes is responsible for the greatest “supply pressure” on immigration, as employers demand an expanding workforce and consumer base, and unimaginative economists and politicians turn to immigration as the only solution to society’s problem of a growing proportion of old age dependents.

Japan stands out as a country that has resisted this, though they have done so by keeping wages and economic productivity extremely stagnant, and now, they too are resorting to a large influx of economic immigrants.

This is not just a problem for advocates of immigration restriction. A few decades ago, if someone spoke of “the population crisis”, you would assume they were talking about the Malthusian catastrophe of the world’s population expanding beyond carrying capacity. Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, published in 1968, started a trend of catastrophizing predictions about the earth expanding beyond its carrying capacity.

Now, if one hears discussion of an incoming population crisis, it’s safe to assume they are talking about the predicted rapid decline in global population after its projected peak this century. It’s all the rage now for neoliberal intellectuals to opine on the causes of and solutions to the universal trend of economic development cratering birthrates. Anyone familiar with Elon Musk’s X feed will know that he and other Silicon Valley libertarians believe population decline is the issue of our time.

Long term projections show that the population collapse will be hugely transformative. Take South Korea, a first world country with the lowest fertility rate in the world. Under current trends, its population of 52 million is projected to drop below 30 million by 2076, and to just 16.5 million by the end of the century.

East Asian countries are especially plagued by population decline. Japan’s population peaked in 2008, at 128 million. The number of births reached another new low in 2023, and the Japanese government projects that by 2070 the population will have fallen by 30%. By 2100, Japan’s population will have shrunk by half, to 63 million.

Things are not much better outside Asia. Iran, an Islamic theocracy, has had a dramatic drop in its fertility rate in recent years, to as low as 1.61 in 2021. Across Europe birthrates are shrinking, even in Scandinavian countries which had seemed to have a lot more resilience to this trend than the rest of Europe. And south of the continent the picture is especially bleak, with Spain and Italy continuing to slump to record lows.

But falling birthrates are just the most obvious and immediately consequential effect of capitalist economic development. Here are some other alarming trends that mass affluence under consumer capitalism has brought us:

There is a mental health crisis in Western societies that is getting worse. About one in five adults in America has a mental illness. One in four young women in the UK has a mental health disorder. The suicide rate rose 655% in Ireland since the 1960s.

We have a loneliness crisis. 61% of young Americans report “serious loneliness”. In the UK, the number of young adults who report having only one or no close friends jumped from 7% to nearly 20% between 2012 and 2021. 22% of millennials in the US report having no close friends.

IQ is declining. The so-called “Flynn effect” of generally increasing IQ’s has ceased, and research across the world has shown intelligence scores declining. The trends of affluent society where having kids is not a necessity has been for lower IQ people to reproduce at higher rates, suggesting this will get worse.

We have a fat crisis. Over half of European adults, and over two thirds of Americans, are overweight.

We have an addiction crisis. Almost 17% of Americans reported a substance abuse problem in the past year. Half of British teens feel addicted to social media.

In short, the affluence and individual liberation delivered by capitalism and mass democracy is not only leading to us no longer replacing ourselves, but there is a startling decline in mental, physical and genetic health which is making populations who experience this cycle incapable of reproducing themselves. Mass society is not dying due to ecological collapse or a proletarian revolution, but through alienation, nihilism and despair. The alienated, secular, modern worldview, unmoored from traditional beliefs which sacralized the mundane, simply lacks the capacity to vitalize populations.

Marx thought his historical materialism could predict the society that would follow of necessity after capitalism. History would culminate in a post-scarcity communist society, where man related freely to his fellow man, and where the distinction between ‘private and common interest’ evaporated. If capitalism is going to reach a crisis due to social collapse and stagnation caused by a population crisis, what can we forecast as the next social formation?

Population decline and populism

In a paper titled Golfing with Trump, researchers looked at the demographic makeup of areas that favoured Donald Trump over his moderate Republican party rival Mitt Romney, who ran for President in 2012. They discovered the common characteristic of areas that swung hard toward Trump was that they were formerly tight-knit, homogeneous communities which had suffered a population and employment decline. This phenomenon is not unique to the United States. Depopulation also seems to precede populism in Europe:

There are important parallels with the experience of other countries which suggest that our results may be more generalisable. For example, the Gilets Jaunes movement came from the declining peripheries of rural France; the rise of the Lega across many parts of Italy has been ignited by the long-term stagnation of the tight-knit communities of the formerly highly successful industrial districts in Northern and Central Italy; the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party in Germany comes, in part, from the declining industrial and small-town communities of Eastern Germany.

A number of recent economic studies show that an ageing population is responsible for a lot of the decline in innovation and entrepreneurship, there is a diminished inflow of young people needed to energize business dynamics and take risks. Economic stagnation follows depopulation everywhere.

The nature of capitalism is such that, if it’s not growing, it’s dying. Capitalism requires compounding economic growth to avoid catastrophe. When a first world economy has just a couple of quarters of no growth, this is considered a crisis. As consumer demand falls, businesses close, and there is a knock-on effect across the economy. Businesses, states and cities are extremely leveraged, and the shock of a dramatic fall in population could trigger a series of defaults and economic crises wherever it occurs.

Depopulation typically does not leave behind great affluence, with the remaining population having fewer mouths to feed with the existing pie. Instead, we observe economic decline everywhere we see significant population decline, and a common struggle for “shrinking cities” is infrastructure crises, as cities for a much larger population must serve a shrinking population at the same cost. Just look at Detroit, a city that lost 40% of its population in 60 years. This might not be such a problem in a society which plans long term and can facilitate degrowth, but our entire economic model functions like a large ponzi scheme, requiring tomorrow’s growth to pay for today.

People in peripheral regions who have watched their communities decline, with no national plan for rejuvenation or development of native industry, naturally turn to populist politics. We should therefore expect populism to continue on an upward trend, as Western elites lack any vision or will to answer this crisis other than hoping the market can provide the innovation and growth needed to lift everyone up, while turning in the short-term to unpopular mass-immigration policies to supplement the population loss.

Changing birthrates, changing politics

Demographic projections can tell us more about the future than the raw population numbers. This is because our political preferences seem to be largely shaped by pre-rational personality traits and tendencies which have a biological foundation.

The research of Jonathan Haidt has revealed that liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral values in thinking about politics. Haidt breaks down our basic moral attachments into six values: care, liberty, fairness, loyalty, authority, and sanctity.

The conclusion from studying conservatives and liberals attachment to these values is that liberals tend to place greatest value on the first three — care, liberty, and fairness — and give little weight to the others. Conservatives value all of these moral ideas. What explains liberals overlooking sanctity, authority and loyalty? If we wanted to connect it to more fundamental personality traits, we might say sanctity is a reflection of people’s natural disgust sensitivity, and both authority and loyalty reflect the degree of what psychologists term “openness”.

Indeed, we find that both high openness and low disgust sensitivity are strong predictors of leftist social views. The more fundamental difference though, is that liberals are more individualistic than conservatives. Ideals like liberty and fairness are rather abstract, individualist-oriented values. Loyalty and authority are important to maintain group cohesion. If your concern is only for yourself as an individual, it’s hard to see why authority has any value in itself. We know that all the traits that predict leftism — openness, neuroticism, individualism — are highly heritable. Looking at who is having children, then, can tell us a lot about the direction society will take.

Genetic studies show political conservatism is heritable, with one of the most comprehensive studies on this estimating its heritability as high as 0.6 (meaning 60% of the variation in conservatism in a population is due to genetics vs. 40% environmental). This is even higher than the estimate for the heritability of religion, which has been estimated to be 30% to 45% heritable.1 Interestingly though, this rises to 0.65 for people who have had “born again” religious conversions.2 This suggests that if we were to see a big return to religion in Western societies on a large scale, there would be a great knock-on effect in the birthrate.

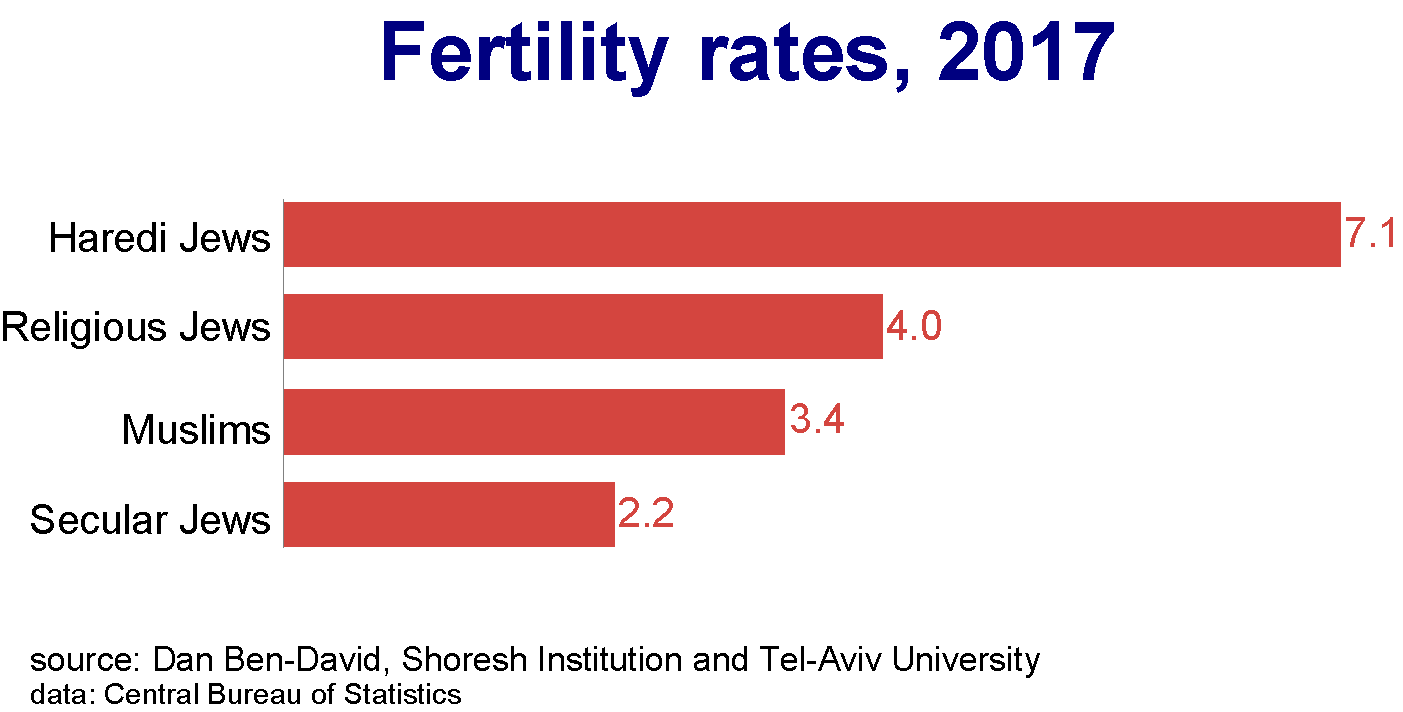

We know conservatism and religiosity are significantly heritable. We also know that religious and conservative people are having more children than the rest of the population. Some of the reasons for this in the case of religion are fairly obvious: all the Abrahamic religions encourage large families and prohibits or discourages contraception. Religious people also suffer less of the neuroticism that puts people off having children, and they tend to be lower IQ — IQ correlates negatively with fertility.3

In a world where the population is collapsing, and having children is a choice fewer and fewer make, the high fertility of certain religious groups can become highly significant in shaping the world that is to come.

Who is checking out?

In The Past is a Future Country, Edward Dutton presents a wealth of data to show that these trends will lead to a future that is more religious and more conservative, where White people are more ethnocentric, where IQ is in decline, and where the extremely liberal that now dominate our elite class make up a smaller and smaller portion of the population. Dutton writes that the simulations resulting from his data conveys “one singular message”:

liberalism is now dying—everywhere. It is dying among the more intelligent; it is dying among the less intelligent. It is dying among blacks; it is dying among whites. It is dying among men; it is dying among women. Only, it hasn’t been dying up till now of course; liberalism has been thriving. It is liberal genes that have been dying. 4

By making a childless life easier and more appealing than ever, liberalism is creating a new kind of evolutionary selection pressure where those less affected by left-liberal ideology will have far more kids relative to the rest of the population. We might even expect this to be exacerbated by environmental concerns in the next century, after all, it has now become common to see respectable liberal publications publish think-pieces on the virtue of living a childless life as a response to climate change. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez once mused in a stream to her followers that “There’s scientific consensus that the lives of children are going to be very difficult. And it does lead young people to have a legitimate question: Is it OK to still have children?”

Research is starting to bear out the anecdotal evidence of increasing numbers of environmentally conscious young people choosing to forgo children due to climate concerns. In 2023, researchers at University College London conducted a review of 13 studies on this topic, and found that all but one concluded stronger concerns about climate change were associated with a desire for fewer children, or none at all.5

These concerns are not limited to privileged western liberals either, a study from the University of Bath found that nearly 40% of 16 to 25 year olds, surveyed from several countries, stated that they were hesitant to have children because of climate change. Climate change is something that worries young people a lot more, and is steadily becoming more central to mainstream political discussion, a trend that will likely spread with time. If the consequence of this ideology is the diminishment of the birthrate among the 40% most environmentally conscious and neurotic of the population, this will basically be selecting against the most left-wing segments of the population, further increasing the relative advantage conservative people already have in birthrates.

The economics of religion

One thing that becomes apparent from looking at these trends is that religion is definitely here to stay. In fact, the religious shall inherit the earth. This would likely come as a great shock to the many skeptics of religion who assume modernity and scientific progress bring about secularism as surely as night follows day.

In fact, sociologists have been predicting the end of religion for decades. It seemed like a simple equation for those skeptical of religion: religion is irrational, a relic of an age where we had to resort to magic and mythology to explain the natural world and comfort us in the face of death. Now that science can explain the workings of nature, and economic development has given us greater freedom from death and disease than ever, people will naturally turn away from the comforting myths of old. If you looked just at elite opinion, this might be a fair assumption.

It now seems clear that reality has not conformed to the “secularization thesis”. Sociologists Rodney Stark and Roger Finke wrote that

After nearly three centuries of utterly failed prophecies … it seems time to carry the secularization doctrine to the graveyard of failed theories, and there to whisper “requiescat in pace.”6

The problem is, most sociologists ignore biology and the heritability of traits like religiosity, and resist the predictive power of raw demographic forecasts in favour of more idealistic theories. But even setting aside the demographic trends discussed, proponents of the secularization thesis would still be wrong.

One particularly frustrating case for the believers of whig history is the United States, which, decades into its status as an economic, cultural and military superpower should have left religion well behind at this point. After all, Europe has become very secular, and the United States is just as modern, more economically powerful, more individualist, and has more free speech. Surely, anyone convinced of the inevitability of secularism would look at the US as the ideal environment for the spread of atheism.

Yet unlike Europe, the US has remained stubbornly Christian. Not only is America more religious than Europe, but it has only gotten more religious since its founding, producing two “great awakenings” of mass religious fervor in the late 19th and mid-20th centuries.

A similar “great awakening” to evangelical Christianity is currently happening in another large country: Brazil. Catholicism has been in decline for decades in Brazil, but rather than moving to atheism, most former Catholics have embraced various Protestant churches. Brazil went from being a country where almost everyone was Catholic, to a country where 31% are evangelical Protestant.

The most obvious similarity between America and Brazil is the preponderance of evangelical Christian denominations. Could this offer a hint as to why they haven’t secularized like Europe? It turns out, sociologists have pursued this thread by studying the “supply side” economics of religion. The sociologist of religion Rodney Stark argued that the degree of a country’s religiosity could be predicted by the degree to which it allows a “free market” of religion.

We are used to thinking this way about economics: if you have a bustling, competitive market environment to produce the best and most cost-effective products, the consumer will be rewarded with more choice and more individually appealing options. In this way, supply itself generates demand, as advocates of the market mechanism celebrate. The logic of supply-side economists was that the way to ignite an economy was thus to recognize this basic truth and simply step out of the way of the free market. Could the same be true of religion? What if a more unregulated religious market just satisfies religious demand better, even demand we didn’t know existed?

Stark argues exactly this. When there is ease of start-up for religious denominations, and they have to compete to deliver the most appealing “product” to bring people to their denomination, there is a general increase in religiosity. In contrast, state religions tend to suffer most from secularization trends, just as monopoly firms suffer inefficiency. The prophet of the invisible hand himself, Adam Smith, noted that among the Church of England:

the clergy, reposing themselves upon their benefices, had neglected to keep up the fervour of faith and devotion of the great body of the people; and having given themselves up to indolence, were incapable of making vigorous exertion in defence even of their own establishment

Obviously, when churches have the backing of the state, and that state is able to control the culture, populations are very religious. But the compromise is that these churches suffer more from the general “desacralization” of society. One can think of the intermingling of church and state in Ireland in the 20th Century, marked by little sacral acts in everyday affairs like the custom of a bishop throwing in the ball to kickstart gaelic football matches of significance. There has been a trend of desacralization which has brought people away from established churches. The argument of Stark, though, is that this is followed by a period of stagnation and then religious revival, as the religious scene becomes “deregulated”.

A number of studies have shown not just greater religiousness in countries with more religious pluralism, but also, within America, areas with more religious pluralism tend to have higher rates of religious participation. It really does seem as if “opening up” the religious space and leaving people a lot of options when it comes to religion increases religiosity, regardless of other trends. But what about Europe? It doesn’t seem like anywhere in Europe is observing a kind of religious revival or outbreak of evangelical Christianity analogous to Latin America.

Stark argued that although established churches have declined in Europe, there still isn’t yet a period of revival because the religious market is not unregulated. Many Protestant countries like Norway still have an official state church that receives privileges from the state. In Catholic countries like Ireland, there is a good deal of de facto regulation and stigma associated with religious pluralism. We also overstate how religious the population was in countries with religious monopolies, since it wasn’t very fashionable or even tolerated to be honest about one’s lack of belief. Even in what we look back on as religious golden ages, the average person was far less pious or wedded to their religious dogma than we imagine.

In his classic survey of religion and magic in Middle Ages Britain, Keith Thomas wrote that

it is problematical as to whether certain sections of the population at this time had any religion at all. Although complete statistics will never be obtainable, it can be confidently said that not all Tudor or Stuart Englishmen went to some kind of church, that many of those who did went with considerable reluctance, and that a certain proportion remained throughout their lives utterly ignorant of the elementary tenets of Christian dogma.

Other religious scholars have described the belief of the average peasant in Middle Ages Europe as a kind of animism and spirit worship which included Christian content. Although almost everyone was nominally Christian, few attended church services:

through most of this era, when more than 90 percent of Europe’s population lived in rural areas, churches were to be found only in towns and cities; therefore hardly anyone could have attended church. Moreover, even after most Europeans had access to a church, whether Catholic or Protestant, most people still didn’t attend, and when forced to do so, they often misbehaved.7

As well as undermining the idealistic view some hold of the pious Middle Ages, this should also dampen the enthusiasm of proponents of the secularization thesis who think the drop off in religion in Europe has been remarkable. But what of this effect of “supply side” changes in religion making Europe less secular?

Two major studies on the effect of religious pluralism on religiosity in Europe concluded that pluralism strongly increases religious participation. Economist Laurence Iannaccone published a study of fourteen Protestant countries in Europe in his paper “The Consequences of Religious Market Structure”,8 while a separate study by Stark looked at majority Catholic countries:

Both studies measured pluralism by the Herfindahl Index, a standard measure of market concentration, and gauged religiousness by weekly church attendance. The studies showed that pluralism has a remarkably strong influence on religiousness: it accounts for more than 90 percent of the total variation in church attendance across these nations.9

As the trend of pluralism and decline of state churches continues in Europe, we should expect periods of stagnation and irreligion to be followed by religious revivals and the growth of smaller sects.

Now recall the study mentioned earlier, which showed that “born again” religious converts have even higher rates of fertility than other religious and conservative people. If the trend of religious pluralism and the increasing demographic dominance of conservatives and religious people leads to a great religious awakening, we should expect the people returning to the faith with newfound fervor to have even higher birthrates, further exacerbating these trends in a positive feedback loop.

A Protestant future?

Reflecting on this, it may seem that the return of religion will come in the form of a mass of small evangelical Protestant sects, similar to America’s last “great awakening”. What hope does Catholicism have as just one among thousands of Christian churches in a religious marketplace?

Latin America was extremely Catholic until the second half of the twentieth century, when restrictions on other religions were lifted and an explosion in Protestantism followed. But far from replacing Catholicism, this explosion of religious pluralism actually energized the Catholic Church. Stark wrote that the Catholic Church had undergone a stunning awakening in Latin America:

Where once the bishops were content with bogus claims about a Catholic land and a reality of low levels of commitment, the Catholic churches in Latin America are now filled on Sundays with devoted members, many of them also active in charismatic groups that meet during the week. And the source of this remarkable change has been the rapid growth of intense Protestant faiths, which created a highly competitive pluralist environment.

Simply put, Latin America has never been so Catholic—and that’s precisely because so many Protestants are there now

Something similar happened in the United States in the 19th Century. After an influx of Catholic immigrants from Europe, many defected to Protestant churches. But the Catholic church in America was energized and adapted to Protestant competition. Soon, the church in America was stronger, and with more active members, than anywhere in Europe. In a pluralist environment, Catholicism and Orthodoxy will undergo selection pressure that makes them more successful at attracting an active clergy.

There is another reason Catholicism and Orthodoxy may be more attractive to people in an environment of pluralism — they are bound up with tradition in a way Protestant churches are not. This may seem like less of an advantage given that the Catholic church has spent decades modernising in response to its declining influence in the modern world. But when people return to religion, especially as the tired castoffs of secularism, they are more likely to appreciate the traditional aspects of the church which seem like a more complete escape from a desacralized world.

We need look no further than the interest in Latin mass within the church. Traditional Latin Mass, as well as other traditional church services, are experiencing explosive growth and, while Traditional Catholics are still just a small minority of Catholics, they are the only demographic of Catholicism that is growing in the West.

Follow the trends

What matters is growth trends, not raw numbers. In general, we tend to underestimate the power of compounding growth, and this certainly applies to making sense of sociological change. Rodney Stark was able to demonstrate how Christianity could conquer the ancient world with a growth rate of just 3 to 4% per year. On its face, this doesn’t sound like a huge growth rate for a sect that had under 10 thousand members at the end of the first century. But then we see how this expands over time. That 3 to 4 percent represents growth of about 40% per decade, which, translated to real numbers looks like this10:

7,500 Christians by the end of the first century (0.02% of sixty million people)

40,000 Christians by 150 AD (0.07%)

200,000 by 200 AD (0.35%)

2 million by 250 AD (2%)

Early Christianity spread through proselytising. Bart Ehrman, in The Triumph of Christianity outlines two main reasons for the Jesus movement’s success. First, Christianity’s doctrinal commitment to spreading the gospel through missionary was something novel in the ancient world. Paul’s insistence on the removal of Jewish dietary restrictions and circumcision and his evangelising to gentiles opened up Christianity to a potential audience of the whole world. Second, Christianity was different from other pagan religions in claiming exclusivity. To be a Christian meant to abandon any other gods or religious beliefs. This was also a radical departure from custom in the pagan world, where worshipping a new god or gods did not mean abandoning the old ones. By being exclusivist, Christianity not only spread itself, but it extinguished pagan beliefs when it did spread.

So Christianity spread mostly through its unique ability to make new converts and dispose of competitor beliefs, but birthrates were also an important factor. Romans practiced infanticide, particularly the practice of “exposure” where infants were left to the elements to either be adopted or die. It was far more common to practice this on infant daughters, since women were of far less value in Roman society.

Christians eschewing this practice would have meant that, aside from the obvious advantage of not killing many of their children, they would also avoid the same kind of gender ratio imbalance Romans had due to mostly removing girls, which could provide a big comparative advantage in birthrates — removing potential mothers from society drags down the birthrate far more than removing men. Some research has suggested this could have been compounded by the population shock caused by plague in the 2nd Century, when Christians would have been far more capable of replenishing their pre-plague numbers due to the sex ratio imbalance.11

Looking at the rise of early Christianity shows that seemingly minor advantages in breeding patterns can create massive change over the course of centuries, and that even these comparative advantages can be massively exacerbated by population shocks.

No church today has the advantage of being the first evangelising religion, as Christianity did in the first century. But there are sects which have massive endogenous growth rates, something which becomes very significant in the midst of a population bomb.

The Mormon church is growing at an even faster rate than early Christianity. They grew by 45.5% in a decade, jumping from 4.2 million in 2000 to 6.1 million in 2010. Stark projected that at a conservative growth rate of 30% per decade, there could be 63 million Mormons by 2080. If they grow by more than 50% per decade, we may enter the next century with this peculiar sect of American Christianity overtaking Buddhism.12 A fine example of the transformative power of birthrates! And as remarkable as this might sound, another obscure American sect received a similar growth rate in the 20th century: the Amish. Despite almost no growth through conversion, their high birthrates have made their numbers increase from 5,000 in 1900 to over 377,000 today.

Can the state defuse the population bomb?

The Amish stand out as a particularly separatist religious group managing to thrive outside modern mass society, but it’s not necessary to give up electricity to achieve this. The other groups succeeding in growing their numbers — traditional Catholics, Orthodox Jews, Mormons — are in, but not of modernity. They manage to retain cultural autonomy while participating (quite successfully) in the modern economy. The mass affluence of modernity is a double-edged sword: it discourages family formation for the traditional core of bourgeois civilization, but for those that choose to do so, it is relatively easy to opt out of ideological modernity without having to accept poverty or isolation.

We can be quite confident that humanity isn’t finished yet. Although the “population bomb” is inevitable, there will always be religious communities eager to endure. The question of our time is not whether the population decline will be reversed, but whether social planners can identify how intentional communities defy the trends and apply the lessons on the scale of mass society.

Typically, politicians have turned to financial incentives as the means of rescuing cratering birthrates. Writing for Unherd, Tom Chivers presented the “progressive way” to boost birthrates. Given that the average number of children people in developed countries want to have is above replacement levels, the most easily fixable problem is addressing the obstacles to people that already want children being able to have them, which are chiefly financial:

rather than policies which coerce women, we could encourage a higher birth rate by creating policies which give women more financial freedom. More generous maternity leave, for instance, seems to raise birth rates, as do simple cash payments to new parents. Subsidising childcare (or helping older people retire more easily, so they can help look after their grandchildren) has a similar effect.

This has been the approach of France and Sweden, two countries with higher than average birthrates by European standards (though still below replacement).

The Swedish social democratic model for family formation was based on the work of economic strategist Gunnar Myrdal, who, at the height of the Great Depression in 1934 wrote a best-selling book on the population crisis. Myrdal argued that the solution to falling birthrates would be making it easy for women to both raise children and have careers.

The solution then, would mostly be generous welfare programs to redistribute wealth to those having families. Sweden now has a world renowned public preschool system and very generous paid parental leave. The French system is also geared heavily towards financial incentives for mothers, and, as a result, Sweden and France spend well above the OECD average on childcare. In each case, these numbers are now propped up by migrants, who have more children than the native populations. Nevertheless, Sweden maintained an above or close to replacement level birthrate throughout the 1990s, when it was still very homogeneous, so it’s hard to argue the Nordic model was not somewhat successful.

In contrast, Italy took a lax approach to falling birthrates, did not look to the welfare state as the solution in the same way, and suffered from poor public finances, and by the 1990s, its birthrate had fallen under 1.2.

But money alone is not enough. Many countries have tried to reverse course with generous government spending and tax incentives, with minimal impact. South Korea has spent over $200 billion trying to reverse its fertility crisis in the past 15 years to little effect — its birthrate currently stands at 0.81. Simply turning on the tap of financial incentives is easy, but purely economic policies don’t change the social structures which more fundamentally dictate attitudes to family formation.

Many of the studies drawn on to support the idea that simple financial rewards directly increase fertility suffer from a flaw: they examine effects in a short window of time, say a few years. With this time frame they are able to show that immediately after the implementation of a monetary reward for childbearing, childbearing increases.

The problem is, this response is likely made up of many people who were going to have children anyway, but just changed their timing, in which case there is no effect on total fertility. This is what a review of programs on family formation throughout the OECD concluded, and it probably explains a lot of the much touted baby boom that happened during COVID lockdowns. After all, if a couple planned on having a child anyway, what better time than during a lockdown with everyone on UBI? That’s not to say finances are irrelevant. Comparing developed countries, like Sweden with Italy, shows that even developed, feminist countries can do a lot to maintain birthrates with a welfare state, but this isn’t enough on its own, and it’s no quick fix, as countries like South Korea and Japan are discovering.

The Georgian model

If you want to see a real success story of a state which has countered the anti-natal trend of modernity, you won’t find it in Nordic welfare states or hyper-religious Muslim countries. Instead, look to the Caucasus. More specifically, look to “the gem of the Caucasus”. Georgia is a small former Soviet republic of 3.7 million people nestled between Turkey and Russia, whose greatest claim to fame is giving the world Joseph Stalin. Its birthrate of 2.08 may not sound remarkable, until one compares it to its neighbours: both Armenia and Azerbaijan have been stagnant at about 1.5 since the start of the century, and Georgia was there too, until it undertook a fascinating experiment.

Georgia is a very religious country, with a population that is 90% Orthodox Christian. In 2007, Patriarch Ilia II of the Georgian Orthodox Church, a figure of great national renown, decided to tackle the problem of declining birthrates head on: he announced to the nation that he would personally baptize and become godfather to any third or above child born to a married couple in Georgia.

This remarkable experiment was a success. Georgian birthrates increased right away, especially the third-order births most affected by the patriarch’s campaign, which nearly doubled between 2007 and 2010, then continued to rise. This happened at a time when the unmarried fertility rate continued to fall.

The Georgian state played its part with a suite of financial incentives in 2013, but the evidence is that the effect of these was minimal compared to the exhortations of the Georgian Patriarch. The economist Lyman Stone, in a report studying Georgia’s mini baby-boom, concluded that the actions of the Patriarch were more decisive than any economic incentive:

The effect [of government subsidies] is substantially smaller than the effect observed from Ilia’s baptism offer, and, of course, the price tag far, far higher, with these programs costing Georgia an appreciable share of its budget.

Nonetheless, it seems plausible that the continued rise of higher-order birth after 2013, while lower-order births fell, could reflect expanded financial incentives. Giving money for kids does have some effect, just not as much as encouragement from beloved religious leaders.

It’s not that financial incentives don’t matter, but it’s social capital that really counts. And the two great sources of social capital outside of liberalism come from religion and national pride, something the small, homogeneous and faithful nation of Georgia can draw on like few others, yet the effect has been a sudden and lasting swing in fertility that some governments would (and will) spend billions to achieve.

The solution for states then, would seem to be a combination of the Nordic model’s economic incentives, with the Georgian model’s social capital incentives. Financial incentives can lessen the gap between desired fertility and actual fertility, and empowering the forces of nationalism and religion can produce the necessary social capital.

Can this be achieved? Using this formula, Israel has managed to maintain a birthrate above replacement and well above what one might expect for a country which has had a developed economy for decades. Israel’s fertility success has drawn on religion, with the ultra-Orthodox women in Israel averaging 6 to 7 children. But even the secular section of the population has stayed above replacement levels, and that’s where this potent combination of economic incentives, the influence of religious attitudes and ethnonationalism come into play.

In a study intended to explain the high secular birthrate of Jews in Israel, the authors attribute it to Israel’s comprehensive welfare regime for child-rearing, coupled with:

the continuing importance of familist ideology and of marriage as a social institution; the role of Jewish nationalism and collective behaviour in a religious society characterized by ethno-national conflict; and a nationalist discourse which defines women as the biological reproducers of the nation.13

Of course, Israel is certainly anomalous, with its unique conflict with Palestine and its history of outside threats keeping a strong national consciousness in the minds of Israelis. Social engineers will look at case studies like Georgia and Israel and realize neither can be precisely replicated by their techniques. No government program can gin up a population that deeply values the perpetuation of its nation, or the word of its religious spokespeople.

Ethnically homogeneous, rooted nations might be easy to take apart, but they can’t be manufactured. The solution of Georgia won’t be the solution of South Korea, Japan or the United States, but they will contain subgroups with their own patriarchs and communities that will create the social capital necessary to make it out the other side of modernity.

Modern globalist civilization is failing to create more humans because it's fundamentally inhuman, misanthropic, and hostile to human life at any age. The very fact that its administrators only understand the crisis of people not having children through the lens of consumer spending, pension funding, and bond market speculation modeling speaks to its inhumanity.

Much ink will be spilled in the coming decades on how to resolve the birthrate crash while maintaining modern mass society. But the core contradiction at the heart of this project is that the alienation from tribal humanity that is integral to modernity is also at the root of the demographic crisis.

If capitalism cannot solve its core contradiction, and produce babies or technology fast enough to replace those on the way out, it may be a tumultuous transition into whatever comes next. Contrary to the techno-optimist’s progressive vision of the future, the vision of humanity’s future offered here is more parochial, more communitarian and more religious. What this will mean for politics on the grand scale remains an open question. But for my part, I find a lot to like in a world more like Georgia.

Bouchard Jr, Thomas J. "Genetic influence on human psychological traits: A survey." Current directions in psychological science 13, no. 4 (2004): 148-151.

Bradshaw, Matt, and Christopher G. Ellison. "Do genetic factors influence religious life? Findings from a behavior genetic analysis of twin siblings." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47, no. 4 (2008): 529-544.

Boutwell, Brian B., Travis W. Franklin, J. C. Barnes, Kevin M. Beaver, Raelynn Deaton, Richard H. Lewis, Amanda K. Tamplin, and Melissa A. Petkovsek. "County-level IQ and fertility rates: A partial test of Differential-K theory." Personality and Individual Differences 55, no. 5 (2013): 547-552.

Dutton, Edward, and J. O. A. Rayner-Hilles. The past is a future country: The coming conservative demographic revolution. Vol. 76. Andrews UK Limited, 2022.

Dillarstone, Hope, Laura J. Brown, and Elaine C. Flores. "Climate change, mental health, and reproductive decision-making: A systematic review." PLOS Climate 2, no. 11 (2023): e0000236.

Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. Univ of California Press, 2000.

Stark, Rodney. The triumph of faith: Why the world is more religious than ever. Simon and Schuster, 2023. Pg. 44

Iannaccone, Laurence R. "The consequences of religious market structure: Adam Smith and the economics of religion." Rationality and society 3, no. 2 (1991): 156-177.

Stark, Rodney. The triumph of faith: Why the world is more religious than ever. Simon and Schuster, 2023. Pg. 59

Stark, Rodney. The rise of Christianity: A sociologist reconsiders history. Princeton University Press, 1996. pg. 7

Philbrick, Kenneth J. "Epidemic Smallpox, Roman Demography, and the Rapid Growth of Early Christianity, 160 CE to 310 CE." PhD diss., Columbia University, 2014.

Stark, Rodney. The rise of Mormonism. Columbia University Press, 2005.

Okun, Barbara S. "An investigation of the unexpectedly high fertility of secular, native-born Jews in Israel." Population Studies 70, no. 2 (2016): 239-257.

Source: Keith Woods

Comments

Post a Comment