Message received

American Airlines advertisement (1968). In addition to selling a product or service, advertising can serve a broader purpose, such as changing our culture.

Dutch people underestimate the crime rate of dark-skinned immigrants while overestimating the crime rate of light-skinned immigrants, including Roma, Turks, and Chinese. Our perception of crime, and reality itself, is being distorted by the messaging of modern culture.

The crime news is unfair to Negroes, on the one hand, in that it emphasizes individual cases instead of statistical proportions ... and, on the other hand, in that all other aspects of Negro life are neglected in the white press which gives the unfavorable crime news an undue weight. Sometimes the white press "creates" a Negro crime wave where none actually exists. (Myrdal, 1944, pp. 655-656)

Gunnar Myrdal wrote An American Dilemma at the dawn of the civil rights era. His book appealed to the educated postwar public, and his thinking became the conventional wisdom, particularly his claim that prejudice makes Black crime seem worse than it really is.

The new conventional wisdom would give rise to a famous novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. First published in 1960, and never out of print since, it tells the story of an innocent Black man who is presumed guilty of a crime. It was the book most often cited by British librarians when asked: "Which book should every adult read before they die?" (Pauli, 2006). Thus arose a recurring theme of modern culture: the Black man as innocent victim.

That theme would spread across the Western world, particularly among the university-educated. It would spread even to countries with no history of black slavery and with few dark-skinned residents until recently.

Crime in the Netherlands: Perception and reality

One such country is the Netherlands. In a recent study, 615 Dutch adults were given the following instructions:

There are many different immigrant groups in the Netherlands. For each of the groups, adjust the slider to your estimation of the crime rate relative to Dutch natives. This means you should adjust the slider to two (2) if you think the crime rate of this group is twice that of natives. (Kirkegaard & Gerritsen, 2021, p. 4)

The actual crime rate of each immigrant group is known from data published by the Dutch government. By measuring how much the respondents overestimated or underestimated the crime rate of each immigrant group, it was possible to measure how negatively or positively they felt toward each immigrant group. Information was also gathered on the respondents’ political affiliation.

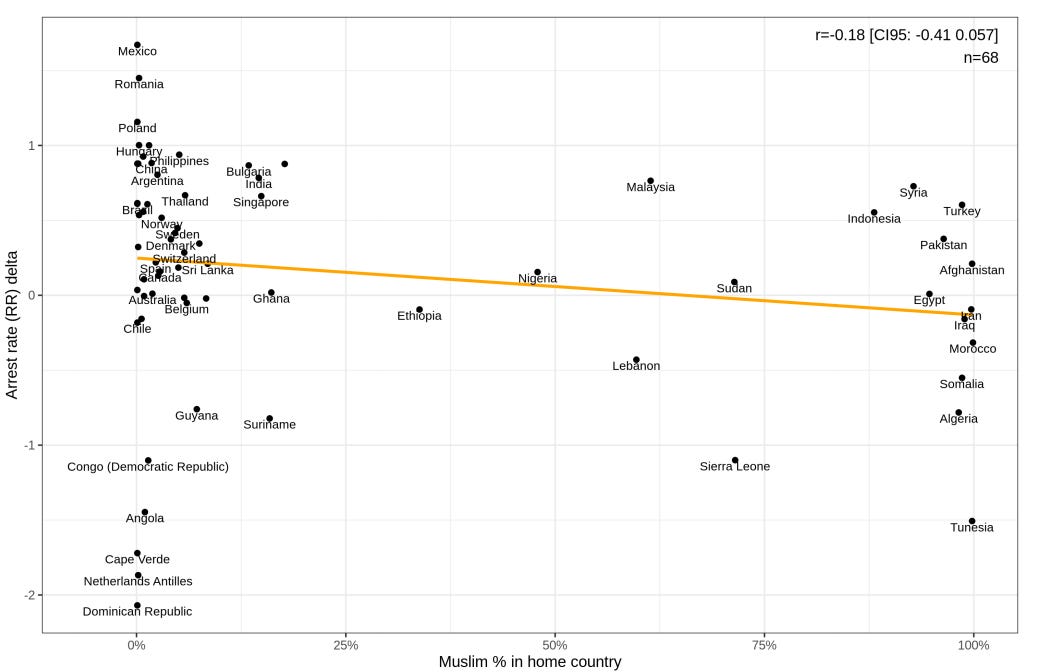

The results are shown on the graph below. On the vertical axis, we see the degree of anti-immigrant or pro-immigrant bias: the immigrant crime rate is overestimated at values above zero and underestimated at values below zero. On the horizontal axis, we see the percentage of Muslims in the immigrants’ home country. The authors of the study were particularly interested in finding out whether the respondents were biased positively or negatively toward Muslims.

Gap between actual and perceived crime rates (y-axis) versus percentage of Muslims in the home country (x-axis) (Kirkegaard & Gerritsen, 2021)

For the study’s authors, the results show a pro-Muslim bias, i.e., the more Muslim the immigrants’ home country, the more their crime rate was underestimated (Kirkegaard & Gerritsen, 2021, pp. 12-17). But this bias did not benefit all Muslim immigrants. In fact, the crime rate was overestimated in the case of those from Indonesia, Syria, or Turkey and correctly estimated in the case of those from Egypt, Iran, or Iraq.

A stronger bias is visible in the above graph. The respondents were most indulgent toward immigrants from certain non-Muslim countries (<25%). These countries are Congo, Angola, Cape Verde, the Netherlands Antilles, and the Dominican Republic. Conversely, the respondents were least indulgent toward immigrants from Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Mexico.

Do you see a pattern? The respondents were underestimating the crime rate of dark-skinned immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean, while overestimating the crime rate of light-skinned immigrants from Europe and elsewhere. The bias was so strong that it distorted how different Muslim groups were perceived—apparently according to their average skin color. North Africans and Somalis were perceived as being less criminal than they really are, while Turks were perceived as being more criminal than they really are.

A systematic pro-Black bias better explains the data than the presumed pro-Muslim bias. The respondents were overestimating the crime rate not only of European immigrants but also of anyone not sufficiently “Black,” including Chinese, Mexicans and, presumably, Roma (see note #1).

How did political affiliation affect the results? Did supporters of “far right” nationalist parties have a weaker pro-Black bias? Apparently not. Although nationalists were more inclined to overestimate the crime rate of Muslim immigrants, they were just as likely to underestimate the crime rate of Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean immigrants. The pro-Black bias was really that pervasive.

How did this bias come about? At least initially, from a desire to counter anti-Black racism by creating a bias in the opposite direction. There has thus been a massive effort to reshape our attitudes and create new norms, particularly by those people who are in a position to do so.

Manufacturing a new culture

Advertising doesn’t exist solely to promote a product or service. It is also used for broader purposes, such as changing the culture. This is no fantasy. Back in 1938, an American trade journal recounted how business had first learned how to manufacture products and bring them to market. Now “the future of business lay in its ability to manufacture customers as well as products” (Printers’ Ink, 1938, p. 397)

Keep in mind the economic situation of the 1930s. This was the Great Depression, and it was necessary to get the economy moving again by changing the mindset of the average person. Frugality had to give way to consumerism, and the free-spending consumer thus became a recurrent theme of advertising. This reason was understandable and hardly sinister. Consumerism helped end the misery of the Depression and give us the affluence of the postwar era.

But the temptation soon arose to change our culture in other ways. Much of what we call “propaganda” began with techniques originally developed to market goods and services, and today those techniques are being used to create a new somatic norm. Between one third and one half of all the faces we see in advertisements are now black, as noted by a contributor to The Washington Times:

While statistics are hard to come by, we can say with confidence that blacks appear far in excess of their 13 percent of the population—so much so that if a foreigner had nothing to go on but our ads, she might reasonably conclude that America is a majority-African-American country. (Gatsiounis, 2019)

We are seeing the same thing in Western countries where Blacks are an even smaller fraction of the population. In the UK, a study of a thousand advertisements shown over two months found that 37% of them featured Blacks, who nonetheless make up only 4% of all British people (Gordon, 2019). A more recent study found even higher non-White overrepresentation in advertisements from the UK (59%), France (55%), and Germany (47%) (Podcast of the Lotus Eaters, 2023).

The aim here is supposedly to right a historical wrong:

Prejudice has made us think that Blacks are more likely to commit crime.

This likelihood is not proven by crime statistics, since Whites get to define what constitutes a “crime.”

Because criminal acts are culturally defined, and because our culture is White-dominated, the problem of “Black crime” is really one of anti-Black bias. It’s a White problem.

Therefore, the solution is to replace anti-Black bias with pro-Black bias by continually exposing Whites to positive images of Black people—as leaders, experts, bosses, neighbors, lovers ...

So goes the argument. Yes, crime is culturally defined. A criminal act is simply the refusal to obey a rule that may vary from one culture to another. But cultures also vary in their potential for development, and certain rules are needed to develop further, like the one forbidding the use of violence to resolve personal disputes. That rule is culturally defined, and it’s absent from many cultures that remain stuck at a low level of development.

Moreover, regardless of how much leeway a culture has in defining its rules, the willingness to obey them is much less culturally defined and much less amenable to change. To a significant degree, it’s a property of the human mind. To comply with “the rules,” you have to obey a prohibition that may run counter to your immediate desires and that must apply to everyone—including you and your family! The willingness to obey abstract rules is not a human universal; it has developed slowly in our species and has gone further in some populations than in others. Some human groups are very fastidious about obeying the rules; others, much less. So this is not a specifically White vs. Black thing.

Ironically, the current “blackfacing” of ads has been most enthusiastically embraced by those populations that are so fastidious about obeying the rules. Like our own. “If it’s bad to underrepresent Black faces in ads, it must be good to overrepresent them, right? The more the better, right?”

So, with the best of intentions, we’re systematically blackfacing our culture to ever higher levels of absurdity. This might be funny, were it not for the consequences.

Note

1. Roma in Western Europe typically identify themselves to the authorities by their country of origin, not their ethnicity. The Dutch respondents greatly overestimated the crime rate of immigrants from Romania, who are widely considered to be mostly Roma:

In these figures, the number relating to the Roma is indeterminate since the ethnicity of asylum seekers is not recorded. Nonetheless, the assumption is that the majority of these applications were made by Roma. Certainly, the press is of this view. Articles discussing Czech or Romanian asylum seekers refer frequently to the Roma. As a result, it is easy for the ordinary member of the public to assume that such groups of applicants are of Roma extraction (Stevens, 2003, p. 440)

References

Gatsiounis, I. (2019). When advertisers fetishize race. Depicting a sanitized racial utopia is unfamiliar to most Americans. The Washington Times, December 2, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2019/dec/2/when-advertisers-fetishize-race/

Gordon, A. (2019). Advertisers are 'trying too hard' to demonstrate diversity by shoehorning in minorities, study finds, as it reveals third of commercials now feature black people. Daily Mail, June 6. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7111087/Advertisers-trying-hard-demonstrate-diversity.html

Kirkegaard, E.O.W., & A. Gerritsen. (2021). A study of stereotype accuracy in the Netherlands: immigrant crime, occupational sex distribution, and provincial income inequality. OpenPsych, June 14 https://doi.org/10.26775/OP.2021.06.14

Myrdal, G. (1944). An American Dilemma. The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Pauli, M. (2006). Harper Lee tops librarians' must-read list. The Guardian, March 2 https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/mar/02/news.michellepauli

Podcast of the Lotus Eaters. (2023). Why always this combo in ads? November 7

Printers’ Ink. A Journal for Advertisers (1938). Fifty Years: 1888-1938. “Chapter IX. Education in Consumption (1930-1938),” pp. 397-400.

Stevens, D.E. (2003). The Migration of the Romanian Roma to the UK: A Contextual Study. European Journal of Migration and Law 5(4): 439-461. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181603322849343

Source: Peter Frost's Newsletter

Comments

Post a Comment