An Assassin Showed Just How Angry America Really Is

An Assassin Showed Just How Angry America Really Is

The murder of UnitedHealth Care CEO Brian Thompson was brutal. The reactions were telling. Elite disdain for the rule of law is leading to a society that is spinning out of control.

In his speech for the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, Senator John Sherman of Ohio made a number of legal points about how to understand competition. But the thrust of his argument was about law and order, for the specter of violence was hanging over a nation that had within living memory experienced a massive and traumatic civil war. And there had been significant, and violent, strikes involving railroads, sometimes nationwide.

Sherman believed America as a free people simply could not sustain the rise of immense concentrations of power in the industrial corporations he saw in his day. Congress had to act, or chaos would reign. Here’s what he said:

You must heed their appeal or be ready for the socialist, the communist, and the nihilist. Society is now disturbed by forces never felt before. The popular mind is agitated with problems that may disturb social order, and among them all none is more threatening than the inequality of condition, of wealth, and opportunity that has grown within a single generation out of the concentration of capital into vast combinations to control production and trade and to break down competition.

Just two years earlier, President Grover Cleveland, in his 1888 State of the Union, discussed that same social chaos in the wake of the rise of large corporations and the inequality they brought.

Communism is a hateful thing and a menace to peace and organized government but the communism of combined wealth and capital, the outgrowth of overweening cupidity and selfishness, which insidiously undermines the justice and integrity of free institutions, is not less dangerous than the communism of oppressed poverty and toil, which, exasperated by injustice and discontent, attacks with wild disorder the citadel of rule.

The social contract, in other words, goes both ways. It’s not just mean for a small clique to run a corrupt system, but Americans who are put upon, if given no peaceful options, will fight back violently. And such a view was not mere rhetoric. In 1892, an anarchist named Alexander Berkman shot Andrew Carnegie’s partner, Henry Clay Frick, who had just broken the most important strike of the decade, of Homestead workers in Pennsylvania. A few years after that, in 1901, an assassin killed President William McKinley. That was a violent time, a post-Civil War era with large number of men trained in weaponry, along with a raw increase in power imbalances.

They were also harkening back to the founding. Mob rule was common in 17th and 18th century England and the colonies, a result of a lack of faith in the laws themselves. Constraining such actions was part of the goal of the framers of the Constitution. As Dave Milton noted in his discussion of the first antitrust laws, when writing those laws, there was an explicit nod to Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an egalitarian set of property owners. Jefferson wasn’t just offering some utopian notion, but instead recognized that the wealthy themselves had an interest in not being violently attacked.

“Egalitarian distribution of wealth,” Milton wrote, “would eliminate the danger that a wealthy minority or an impoverished majority would seize governmental power in order to redistribute wealth for its own selfish benefit. In other words, unequal distribution meant either plutocracy or mob rule.” And this notion goes straight through the 20th century. Post-WWII era suburban architect William Levitt pithily updated Jefferson’s argument when he said, “No man who owns his own house and lot can be a Communist. He has too much to do.” Barack Obama even made this observation in 2009 when he told bankers at the height of the financial crisis that “my administration is the only thing between you and the pitchforks."

In other words, one school of political thought is that a key way to maintain social order is through legitimacy. The people had to be persuaded that corporations and government were on their side. “If we desire respect for the law,” said Louis Brandeis, “we must first make the law respectable.”

Early on Wednesday morning, an assassin killed UnitedHealth Care CEO Brian Thompson in Midtown Manhattan. UnitedHealth Care is the biggest health insurer in America, a subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group, which is the largest employer of doctors, a giant pharmacy benefit manager, a technology firm, and so forth, basically a giant health care platform. (I wrote up how these types of firms formed in 2020 in a piece called How CVS Became a Health Care Tyrant.)

We don’t know why the killer did it, though he scrawled “deny” “defend” and “depose” on bullet casings, indicating that he at least wants people to believe it’s a result of unjust and routine denials of care by the health insurance giant. "There had been some threats," his wife Paulette Thompson told NBC News. "Basically, I don’t know, a lack of coverage?” While I’m immediately suspicious of such a neat and clean-sounding motive, if you do take it on face value, that does sound a lot like the mob rule Jefferson, Sherman, Cleveland, and others warned about.

And the reactions to the murder were shocking if not surprising, because of how so many Americans seemed to endorse such vigilante-style acts of violence. Of course the *official* reaction was the polite one, aka one mustn’t speak ill of the dead. Mourning, lamenting a tragedy, talking good of the dead, interviewing friends et al. A good example of this narrative was the Wall Street Journal obituary, painting a picture of a small town man done good, beloved by his colleagues, struck down by a tragic murder. “Steve Nelson, a former UnitedHealth executive who now runs CVS Health’s Aetna unit, said Thompson would sometimes defuse tension over a difference of opinion by offering to arm-wrestle over the matter. ‘He was the smartest guy in the room, but somehow not in an annoying way,’ Nelson said.”

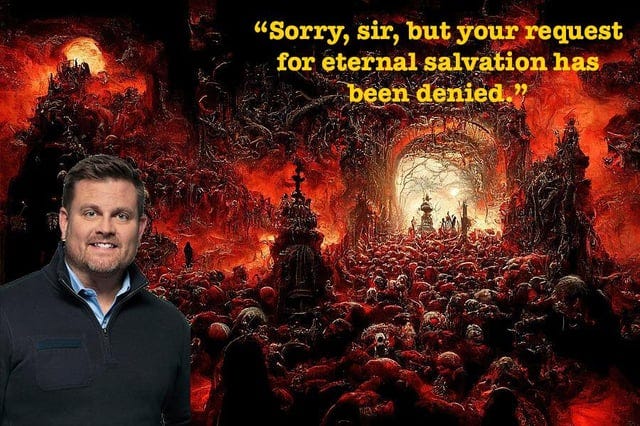

But almost everywhere outside of such official channels, pouring out through every seam of the internet, was a different message, a message of raw unadulterated hatred, of “this guy deserved it.” This picture, for instance, came from a Reddit channel dedicated to nursing. Yes, these are the people who heal for a living, and they are mocking this guy’s death. “My patients died while those bitches enjoyed 26 million dollars,” said one. There are endless angry comments about Thompson from people who try to stop people from dying. That’s how bad it is.

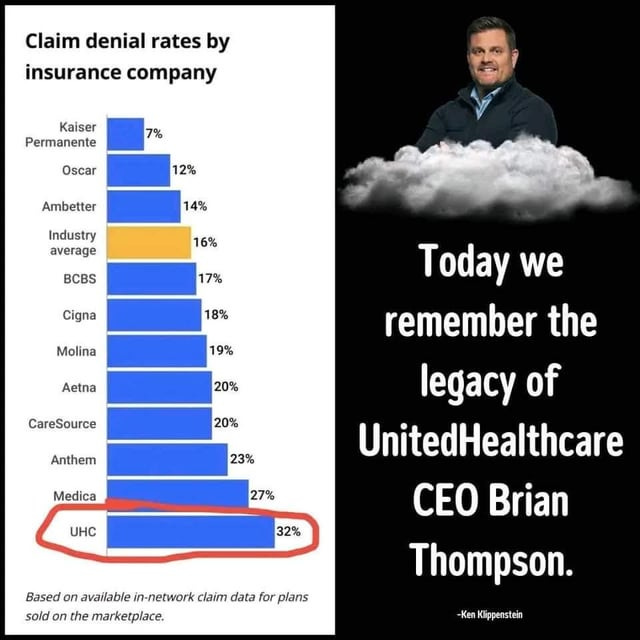

It’s pretty obvious why Americans would feel this way about health insurance executives. UnitedHealth Group is one of the most toxic and unaccountable companies in America, a $400 billion behemoth that systematically denies care to millions of Americas, was smack dab in the middle of the opioid crisis, cheats the government, surveils its customers, harms independent doctor’s practices, and has executives who routinely engage in what looks like insider trading.

But these scandals understate the more mundane reality of having health insurance in America, paying thousands of dollars a month, and knowing that if you get sick you have a not-insignificant chance of being treated unfairly anyway and going bankrupt. In other words, one way to think of it is that Brian Thompson was basically running a death panel for 50 million Americans and making $10 million a year doing so. As Moe Tkacik put it at the American Prospect "Only about 50 million customers of America’s reigning medical monopoly might have a motive to exact revenge upon the UnitedHealthcare CEO."

Here’s how independent journalist Ken Klippenstein characterized it, in a manner designed to highlight the brutal nature of our health care system.

On the Daily Show, the joke was, ‘But now the cops just need to narrow down their list of suspects to anyone who hates their health care plan and has access to guns. It should be solved in no time.”

At least some elites understood the problem. Harvard Business School professor Ranjay Gulati told the New York Times there’s an issue. “There’s a latent undercurrent here of how frustrated people are with the health care industry,” he said. “I’m not condoning the action in any way, but there’s a lot of soul-searching we have to do about an industry that consumes nearly 20 percent of our G.D.P. and yet our outcomes are not nearly as good as countries that spend half as much.” Indeed, despite all the yawping about health care reform, Obamacare, antitrust, abundance, Trump, draining the swamp, whatever, the widespread and almost gleeful reaction to the murder shows that all of that political rhetoric is perceived as useless busywork. Americans didn’t exactly say ‘Just shoot the guy,’ but they came very close.

And that gets back to the question of legitimacy. While normal people who have to deal with health insurance understand at a visceral level the absolute terror UnitedHealth inspires in all of us, our leadership class does not. Take one of the first antitrust suits brought by the Biden Justice Department, which was actually against UnitedHealth Group, because that company was trying to buy Change Health, the dominant payment network for hospitals and pharmacies, kind of like Visa/Mastercard in health care. The argument was that UHG would misuse the data that flowed over its wires, to surveil its customers and rivals.

The judge, a conservative Republican corporate type named Carl Nichols, wrote a stinging rebuke of the Department of Justice in 2022, ruling in favor of UnitedHealth Group. After Nichols cleared the merger, of course, disaster ensued. Change Health’s network got hacked and stopped working for more than a month, leading to cash crunches at hospitals, doctor’s practices, and pharmacists. Ninety-four percent of hospitals, for instance, were affected, and roughly 40% had more than half of their revenue affected by the hack. What did UnitedHealth Care do? Well, they went shopping, engaging in mergers with provider practices hurt by their own malfeasance. That’s how these guys operate, and why they are so hated.

But it takes a village to corrupt a health care system, it wasn’t this company alone that did it, but an entire political class. So it’s worth looking at Nichols’s decision, to show how our leadership class has lost its legitimacy. Here’s what I wrote at the time:

And yet, the judge who ruled against the Antitrust Division, Carl Nichols, argued as a key reason to dismiss the DOJ’s suit and I’m not joking, that UnitedHealth has “a culture of trust and integrity.” The case involves whether UGH, in buying a company with lots of data on what its competitors do, would ever take a peek at that data to benefit itself. Having access to that data is an obvious conflict of interest, but Nichols basically said, ‘Nah, UHG execs are good guys.’

What was his evidence? Here again, I’m not kidding, Nichols said the evidence that UGH would not take advantage of rivals is that the company’s CEO, Andrew Witty, said so. Doing so, Witty argued, “would be against the tone, the culture, the rules, everything we stand for in the organization.” The chief operating officer and the chief privacy officer also stood as stalwart honorable men. “I honestly think you would see a lot of people quitting,” said Peter Dumont, UHG’s Chief Privacy Officer, in response to a question about why the firm wouldn’t engage in surveillance on its rivals despite now having the means to do so.

While I believe in the rule of law and antitrust, this kind of decision does show the fruitlessness of working through the system. An extremely mild attempt to stop a massively swollen and corrupt goliath from getting even bigger through acquisition took significant government resources, and then was thwarted by a judge whose rationale was that UnitedHealth Group has a culture of integrity. And my guess is that Nichols is friends with lawyers for the giant company. There is a tiny percentage of Americans who think like Nichols does, the problem is they all likely serve as judges or in important policy roles. (They also have significant investments in these corporations; Nichols for instance owned $50,000 of UHG bonds when he was hearing the case.)

To make the obvious point, of course this murder was awful. And right now, CEOs are ramping up security, in the hopes that they can protect themselves and calm their fears.

While I really dislike a lot of these people, none of us should want to live in a country where assassination becomes a method of political expression. It’s hard to see democracy surviving if elected leaders and corporate leaders feel they might be shot at any point. And that’s why we have to actually get our laws working again. I hope that men like Carl Nichols and Fortune 500 CEOs start to wake up, and see that there is deep rage outside their clubby environs that can’t be fixed with security measures but must be addressed by some measure of social obligation to the people who live here.

After all, societies that give citizens no way to control their own lives, but put the fate of their people in the hands of distant masters with no concern at all for their wellbeing, invite disaster. We’ve always known that. It’s one of the main reasons for the passage of our antitrust laws. So I hope we can get some control over our society again, before we truly do spin out of control.

Source: BIG by Matt Stoller

In his speech for the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, Senator John Sherman of Ohio made a number of legal points about how to understand competition. But the thrust of his argument was about law and order, for the specter of violence was hanging over a nation that had within living memory experienced a massive and traumatic civil war. And there had been significant, and violent, strikes involving railroads, sometimes nationwide.

Sherman believed America as a free people simply could not sustain the rise of immense concentrations of power in the industrial corporations he saw in his day. Congress had to act, or chaos would reign. Here’s what he said:

You must heed their appeal or be ready for the socialist, the communist, and the nihilist. Society is now disturbed by forces never felt before. The popular mind is agitated with problems that may disturb social order, and among them all none is more threatening than the inequality of condition, of wealth, and opportunity that has grown within a single generation out of the concentration of capital into vast combinations to control production and trade and to break down competition.

Just two years earlier, President Grover Cleveland, in his 1888 State of the Union, discussed that same social chaos in the wake of the rise of large corporations and the inequality they brought.

Communism is a hateful thing and a menace to peace and organized government but the communism of combined wealth and capital, the outgrowth of overweening cupidity and selfishness, which insidiously undermines the justice and integrity of free institutions, is not less dangerous than the communism of oppressed poverty and toil, which, exasperated by injustice and discontent, attacks with wild disorder the citadel of rule.

The social contract, in other words, goes both ways. It’s not just mean for a small clique to run a corrupt system, but Americans who are put upon, if given no peaceful options, will fight back violently. And such a view was not mere rhetoric. In 1892, an anarchist named Alexander Berkman shot Andrew Carnegie’s partner, Henry Clay Frick, who had just broken the most important strike of the decade, of Homestead workers in Pennsylvania. A few years after that, in 1901, an assassin killed President William McKinley. That was a violent time, a post-Civil War era with large number of men trained in weaponry, along with a raw increase in power imbalances.

They were also harkening back to the founding. Mob rule was common in 17th and 18th century England and the colonies, a result of a lack of faith in the laws themselves. Constraining such actions was part of the goal of the framers of the Constitution. As Dave Milton noted in his discussion of the first antitrust laws, when writing those laws, there was an explicit nod to Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an egalitarian set of property owners. Jefferson wasn’t just offering some utopian notion, but instead recognized that the wealthy themselves had an interest in not being violently attacked.

“Egalitarian distribution of wealth,” Milton wrote, “would eliminate the danger that a wealthy minority or an impoverished majority would seize governmental power in order to redistribute wealth for its own selfish benefit. In other words, unequal distribution meant either plutocracy or mob rule.” And this notion goes straight through the 20th century. Post-WWII era suburban architect William Levitt pithily updated Jefferson’s argument when he said, “No man who owns his own house and lot can be a Communist. He has too much to do.” Barack Obama even made this observation in 2009 when he told bankers at the height of the financial crisis that “my administration is the only thing between you and the pitchforks."

In other words, one school of political thought is that a key way to maintain social order is through legitimacy. The people had to be persuaded that corporations and government were on their side. “If we desire respect for the law,” said Louis Brandeis, “we must first make the law respectable.”

Early on Wednesday morning, an assassin killed UnitedHealth Care CEO Brian Thompson in Midtown Manhattan. UnitedHealth Care is the biggest health insurer in America, a subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group, which is the largest employer of doctors, a giant pharmacy benefit manager, a technology firm, and so forth, basically a giant health care platform. (I wrote up how these types of firms formed in 2020 in a piece called How CVS Became a Health Care Tyrant.)

We don’t know why the killer did it, though he scrawled “deny” “defend” and “depose” on bullet casings, indicating that he at least wants people to believe it’s a result of unjust and routine denials of care by the health insurance giant. "There had been some threats," his wife Paulette Thompson told NBC News. "Basically, I don’t know, a lack of coverage?” While I’m immediately suspicious of such a neat and clean-sounding motive, if you do take it on face value, that does sound a lot like the mob rule Jefferson, Sherman, Cleveland, and others warned about.

And the reactions to the murder were shocking if not surprising, because of how so many Americans seemed to endorse such vigilante-style acts of violence. Of course the *official* reaction was the polite one, aka one mustn’t speak ill of the dead. Mourning, lamenting a tragedy, talking good of the dead, interviewing friends et al. A good example of this narrative was the Wall Street Journal obituary, painting a picture of a small town man done good, beloved by his colleagues, struck down by a tragic murder. “Steve Nelson, a former UnitedHealth executive who now runs CVS Health’s Aetna unit, said Thompson would sometimes defuse tension over a difference of opinion by offering to arm-wrestle over the matter. ‘He was the smartest guy in the room, but somehow not in an annoying way,’ Nelson said.”

But almost everywhere outside of such official channels, pouring out through every seam of the internet, was a different message, a message of raw unadulterated hatred, of “this guy deserved it.” This picture, for instance, came from a Reddit channel dedicated to nursing. Yes, these are the people who heal for a living, and they are mocking this guy’s death. “My patients died while those bitches enjoyed 26 million dollars,” said one. There are endless angry comments about Thompson from people who try to stop people from dying. That’s how bad it is.

It’s pretty obvious why Americans would feel this way about health insurance executives. UnitedHealth Group is one of the most toxic and unaccountable companies in America, a $400 billion behemoth that systematically denies care to millions of Americas, was smack dab in the middle of the opioid crisis, cheats the government, surveils its customers, harms independent doctor’s practices, and has executives who routinely engage in what looks like insider trading.

But these scandals understate the more mundane reality of having health insurance in America, paying thousands of dollars a month, and knowing that if you get sick you have a not-insignificant chance of being treated unfairly anyway and going bankrupt. In other words, one way to think of it is that Brian Thompson was basically running a death panel for 50 million Americans and making $10 million a year doing so. As Moe Tkacik put it at the American Prospect "Only about 50 million customers of America’s reigning medical monopoly might have a motive to exact revenge upon the UnitedHealthcare CEO."

Here’s how independent journalist Ken Klippenstein characterized it, in a manner designed to highlight the brutal nature of our health care system.

On the Daily Show, the joke was, ‘But now the cops just need to narrow down their list of suspects to anyone who hates their health care plan and has access to guns. It should be solved in no time.”

At least some elites understood the problem. Harvard Business School professor Ranjay Gulati told the New York Times there’s an issue. “There’s a latent undercurrent here of how frustrated people are with the health care industry,” he said. “I’m not condoning the action in any way, but there’s a lot of soul-searching we have to do about an industry that consumes nearly 20 percent of our G.D.P. and yet our outcomes are not nearly as good as countries that spend half as much.” Indeed, despite all the yawping about health care reform, Obamacare, antitrust, abundance, Trump, draining the swamp, whatever, the widespread and almost gleeful reaction to the murder shows that all of that political rhetoric is perceived as useless busywork. Americans didn’t exactly say ‘Just shoot the guy,’ but they came very close.

And that gets back to the question of legitimacy. While normal people who have to deal with health insurance understand at a visceral level the absolute terror UnitedHealth inspires in all of us, our leadership class does not. Take one of the first antitrust suits brought by the Biden Justice Department, which was actually against UnitedHealth Group, because that company was trying to buy Change Health, the dominant payment network for hospitals and pharmacies, kind of like Visa/Mastercard in health care. The argument was that UHG would misuse the data that flowed over its wires, to surveil its customers and rivals.

The judge, a conservative Republican corporate type named Carl Nichols, wrote a stinging rebuke of the Department of Justice in 2022, ruling in favor of UnitedHealth Group. After Nichols cleared the merger, of course, disaster ensued. Change Health’s network got hacked and stopped working for more than a month, leading to cash crunches at hospitals, doctor’s practices, and pharmacists. Ninety-four percent of hospitals, for instance, were affected, and roughly 40% had more than half of their revenue affected by the hack. What did UnitedHealth Care do? Well, they went shopping, engaging in mergers with provider practices hurt by their own malfeasance. That’s how these guys operate, and why they are so hated.

But it takes a village to corrupt a health care system, it wasn’t this company alone that did it, but an entire political class. So it’s worth looking at Nichols’s decision, to show how our leadership class has lost its legitimacy. Here’s what I wrote at the time:

And yet, the judge who ruled against the Antitrust Division, Carl Nichols, argued as a key reason to dismiss the DOJ’s suit and I’m not joking, that UnitedHealth has “a culture of trust and integrity.” The case involves whether UGH, in buying a company with lots of data on what its competitors do, would ever take a peek at that data to benefit itself. Having access to that data is an obvious conflict of interest, but Nichols basically said, ‘Nah, UHG execs are good guys.’

What was his evidence? Here again, I’m not kidding, Nichols said the evidence that UGH would not take advantage of rivals is that the company’s CEO, Andrew Witty, said so. Doing so, Witty argued, “would be against the tone, the culture, the rules, everything we stand for in the organization.” The chief operating officer and the chief privacy officer also stood as stalwart honorable men. “I honestly think you would see a lot of people quitting,” said Peter Dumont, UHG’s Chief Privacy Officer, in response to a question about why the firm wouldn’t engage in surveillance on its rivals despite now having the means to do so.

While I believe in the rule of law and antitrust, this kind of decision does show the fruitlessness of working through the system. An extremely mild attempt to stop a massively swollen and corrupt goliath from getting even bigger through acquisition took significant government resources, and then was thwarted by a judge whose rationale was that UnitedHealth Group has a culture of integrity. And my guess is that Nichols is friends with lawyers for the giant company. There is a tiny percentage of Americans who think like Nichols does, the problem is they all likely serve as judges or in important policy roles. (They also have significant investments in these corporations; Nichols for instance owned $50,000 of UHG bonds when he was hearing the case.)

To make the obvious point, of course this murder was awful. And right now, CEOs are ramping up security, in the hopes that they can protect themselves and calm their fears.

While I really dislike a lot of these people, none of us should want to live in a country where assassination becomes a method of political expression. It’s hard to see democracy surviving if elected leaders and corporate leaders feel they might be shot at any point. And that’s why we have to actually get our laws working again. I hope that men like Carl Nichols and Fortune 500 CEOs start to wake up, and see that there is deep rage outside their clubby environs that can’t be fixed with security measures but must be addressed by some measure of social obligation to the people who live here.

After all, societies that give citizens no way to control their own lives, but put the fate of their people in the hands of distant masters with no concern at all for their wellbeing, invite disaster. We’ve always known that. It’s one of the main reasons for the passage of our antitrust laws. So I hope we can get some control over our society again, before we truly do spin out of control.

Source: BIG by Matt Stoller

Comments

Post a Comment