Jeff Bezos Just Taught Liberal Elites How Oligarchy Really Works

Jeff Bezos Just Taught Liberal Elites How Oligarchy Really Works

Bezos was feted as the savior of the Washington Post in 2013, now he's reviled for mass layoffs. But it's also Google who helped crush the paper. Liberal elites are starting to learn about oligarchy.

In August of 2019, Senator Bernie Sanders faced negative coverage of his Presidential campaign by a vaunted national newspaper, the Washington Post. This publication was revered in D.C., having broken the Watergate scandals and brought down Richard Nixon in the 1970s. It had delivered a host of important stories over the decades since, seen as a public trust so important that Steven Spielberg made a movie about the publisher’s decision to help publish the Pentagon Papers. But like most newspapers, it had stumbled in the early 2010s.

At the time, newspapers were doing badly due to what they thought was a decline in ad spending due to the financial crisis. Philanthropists were musing on how to save journalism, and tech barons, such as Salesforce’s Marc Benioff and Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes, were buying legacy publications and pledging to reinvent them with capital and innovative savvy.

In 2013, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post for $250 million. Local elites in D.C. were immensely grateful to Bezos. The paper adopted the slogan “Democracy Dies in Darkness” and took on a sharp edge against Donald Trump. Bezos had deep pockets, and had saved the town’s pride.

Six years later, Sanders, running for President against what he called the billionaire class, did something unusual in polite liberal society. He said Bezos had an incentive to shade coverage of politicians he didn’t like. Sanders had been discussing how Amazon doesn’t pay enough in taxes.

“See, I talk about that all of the time. And then I wonder why The Washington Post — which is owned by Jeff Bezos, who owns Amazon — doesn’t write particularly good articles about me. I don’t know why. But I guess maybe there’s a connection.”

And that comment created a bitter reaction within D.C. towards the populist politician. The executive editor of the Washington Post, a deeply respected man named Marty Baron (played by Liev Schreiber in the 2015 film “Spotlight”), responded the way all of D.C. felt. He called Sanders a conspiracy theorist.

How dare Sanders cast shade on the willingness of a benevolent billionaire to steward a public institution like the Washington Post?!? While most journalists and readers of the Post would in other contexts understand the conflict of interest at issue here, here they felt differently. What newspapers write, they believed, is truthful, and neutral, and objective. Bezos was naught but a kindly check-writer, perhaps ruthless at Amazon, but now ascended to the pantheon of philanthropy. Who is this rag-tag old Jewish socialist to annoy us with his complaining?

What a difference six years makes.

Yesterday, the Washington Post engaged in layoffs across the organization, getting rid of the Middle East team, war correspondents, its entire sports department, and everyone in the West coast office who covers big tech. Local coverage will be cut to just 12 people. Overall, Bezos is firing 300 out of 800 reporters, decimating what is widely regarded as a key newspaper covering government in America. “It’s an absolute bloodbath,” said one employee.

Importantly, the paper also fired the reporter tracking Amazon. The stated reason is that the company is losing money due to a loss of local market power, falling ad revenue, and generative AI.

Mr. Murray further explained the rationale in an email, saying The Post was “too rooted in a different era, when we were a dominant, local print product” and that online search traffic, partly because of the rise of generative A.I., had fallen by nearly half in the last three years. He added that The Post’s “daily story output has substantially fallen in the last five years.”

Bezos’ change of heart has horrified the D.C. elites who feted him in 2013. It’s so bad that even the local influence peddlers are angry. Here’s a Democratic lobbyist for big tech, a man named Matt Bennett, offering a public and shocking complaint against the founder of Amazon.

Why the open rage? Some of the anger is coming from a place of delusion and arrogance. I’m not a particular fan of the Washington Post. They helped get us into the war in Iraq and endorsed a series of obnoxious local candidates for as long as I’ve paid attention to politics. Even the vaunted Woodward and Bernstein investigations into Watergate are exaggerated. Also, D.C. writ large is a community that looks down on Trump. The Atlantic called these layoffs “The Murder of the Washington Post, while the New Yorker titled their article How Jeff Bezos Brought Down the Washington Post.

And what of the executive editor, that Marty Baron fellow? Now retired, he called the layoffs “one of the darkest days” in the history of one of the world’s greatest news organizations,” and attacked Bezos for being “gutless.” There was no apology to Sanders, and he even thanked his former boss, saying that he was “personally grateful for Jeff Bezos’s steadfast support and confidence during my eight-plus years as The Post’s executive editor.” It’s remarkable that Baron’s mewling statement expressed less genuine outrage than that of a big tech lobbyist, but it is a belated acknowledgment of a problem.

But mostly, the frustration is reasonable. The Washington Post is a local paper with good coverage of local events and government policy, and there are a lot of reporters who work on national and international questions that would otherwise go unnoticed. It’s where people who live in D.C. read their favorite sports columnist, find out stuff about the local industry, and learn about how the snow will be plowed. Like any local community, people here are upset about losing the newspaper.

That’s not to say that the newspaper is doing well, because it’s not. There are financial problems, as there are across the industry. Since 2005, the number of people working at newspapers has dropped by 75%, and a third of U.S. counties now have no daily newspaper. But while most regional papers don’t have the scale to transition to a subscription model, a few - like the New York Times and Wall Street Journal - do. And for a time, the Washington Post did as well.

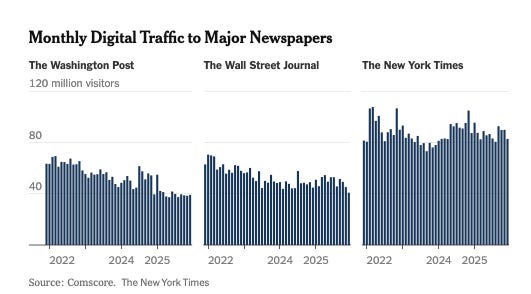

But Bezos himself ruined this opportunity for the paper. In 2024, Bezos intervened in the editorial page to prevent an endorsement of Kamala Harris, which was a violation of the promise he made in 2013 when he bought the paper. That decision led to 200,000 subscription cancelations. We don’t know how many the paper has left, but the guess was that it had 2.5 million before Bezos’s intervention. So the drama aside, that’s… not a bad number of customers. And actual traffic to the Washington Post is still pretty good. Here’s a chart from the New York Times.

The Washington Post has 40 million people visiting the website every month, it is a credible and trustworthy brand, and the region needs, if nothing else, local news. Those 200,000 subscribers are clearly willing to pay for news, they are just not willing to pay for news delivered in an untrustworthy manner.

So most observers don’t think the layoffs are some sort of inevitable choice, but a discrete decision to destroy the paper. Why would Bezos ruin this asset instead of selling it to someone else? There are likely two big reasons. The first is that the Washington Post used to be an extremely useful political tool for Bezos, but it no longer is. And the second is financial and political - the Washington Post is being pillaged by Google’s illegal adtech monopoly. Interestingly, many media outlets are suing Google over this situation, such as Vox, The Atlantic, Business Insider, McClatchy Media Co., Slate, and Advance Publications. But the Washington Post, owned by a foe of antitrust law, is not.

And this curious fact that the Washington Post is leaving money on the table to avoid litigating on antitrust suggests that Bezos never had any good intentions with the Post in the first place. To understand why, let’s go back to the original purchase of the paper in 2013. While most saw Bezos as a savior, there was a less magnanimous interpretation of his acquisition.

There have always been media barons, but those barons made their money in media. Bezos, however, was making his money elsewhere, and subsidizing media. At the time of the purchase, Amazon was starting to be in the crosshairs of regulators and media outlets over its consolidation of the book industry, as well as its advantages over retailers due to sales tax loopholes. Here’s the cover of The New Republic in 2014:

The year before buying the paper, Bezos made other moves to fortify his political power. He put the deeply wired super-lawyer Jamie Gorelick on the Amazon board, likely because she had pull with the Obama Department of Justice. A few years later, he bought a giant mansion in D.C., with the assumption he would assume the role of the Graham family as a local social leader. Then he awarded Amazon’s “second headquarters” to the D.C. area.

In other words, the purchase of the Washington Post in retrospective appears like part of a campaign to curry favor with political and media elites in D.C. in order to get government contracts, protect Amazon’s business, ward off scrutiny, and manipulate politics. It looks exactly as Sanders suggested.

Just a few years after Bezos bought the Post, Donald Trump said in campaign speeches that Bezos had an “antitrust” problem. If elected, he said he’d go after the company. In 2017, Lina Khan’s famous law review article, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, went viral. Trump, despite prodding from allies in real estate, angry that Amazon had hurt their shopping mall investments, didn’t attack Amazon. But Joe Biden did, appointing Khan to run the Federal Trade Commission. In September 2023, the FTC sued Amazon for monopolization, a case that is still in process. The Washington Post became less useful, once the case got filed.

When Trump ran again in 2024, he made it very clear that he would retaliate against business leaders who were hostile and reward those who were deferential. So the political value of the Washington Post disappeared, and “Democracy Dies in Darkness” turned into a sick joke, like Google’s “Don’t Do Evil.” In other words, one interpretation is that Bezos bought the Washington Post to delay an antitrust case and curry favor with politicians. He failed at blocking the case, and so now it’s important to shut down ongoing critical coverage of both his company and the Trump administration.

And that’s where we get to the monopoly problem, which the Washington Post itself reported last April.

As Judge Leonie Brinkema ruled, Google has been systematically monopolizing the technology and process for selling advertising on the open web, exactly the kind of ads the Post sells. Google controls ad revenue and distribution, and it has used that power to kill thousands of newspapers in America by monetizing the work they do and taking that money for itself. And it is this behavior, the diversion of revenue from publishers to tech monopolies, that led to the Washington Post becoming the plaything of a billionaire, who then threw it away.

In 2022, I described the basic dynamic that allows Google to appropriate billions from newspapers and divert it to its own properties.

By 2014, Google was no longer just a search engine; if you bought advertising, sold advertising, brokered advertising, tracked advertising, etc, you were doing it on Google tools. It tied its products togethers so you couldn’t get access to Google search data or YouTube ad inventory unless you used Google ad software, which killed rivals in the market. It downgraded newspapers who tried to negotiate different terms.

This leverage came from Google’s control of both the distribution of news and the software and data underpinning online ad markets. Roughly half of Americans report getting news from social media, while 65% get it from a search engine like Google. That means newspapers are getting a lot of their customers from entities who compete with them to sell ads, often to their same audience. And they must use the software offered by Google to sell those ads, and often display content on Google News under the terms that Google demands, which includes allowing Google to display much of the article itself on its own properties. (If you want a good example of how Google steals content, read this piece on what it did to Celebrity Net Worth.)

Over these years, Google introduced Google News and standards for web pages that privileged its own services, cut favorable deals with adblockers, and fought against things like header bidding, which was an attempt by publishers/advertisers to get better prices than Google was offering for ad inventory. Google began demanding terms for data and formatting that publishers had no choice but to supply. In 2017, for instance, the Wall Street Journal refused to allow Google search users to read its content for free, instead locating its content behind a paywall. Google downgraded the status of the newspaper in its search rankings. While subscriptions went up, traffic to the newspaper dropped by 44%.

Over the course of these twenty years, under Republican and Democratic administrations, neither Congress nor the FTC created mandatory public rules over the use of data, and enforcers pursued no meaningful antitrust suits to stop big tech firms. In 2012, the FTC Bureau of Economics, in one of the all time most embarrassing episodes for economics, actively killed a suit that could have stopped the monopolization of the search market. So Google became a monopoly in the advertising industry, not just over search ads, but over most online advertising markets. Last year, Google’s global revenue amounted to $257.6 billion, which is nearly all from advertising. That’s a huge amount of money, some of which used to go to finance journalism but now goes to private jets in Palo Alto.

The financial problems Google has fostered have turned a business based on credibility into a charity based on the dependency on an oligarch’s goodwill. Consider that if the Washington Post could profit by producing good journalism, Bezos would be less likely to gut its operations. And even if Bezos did gut it, it would be easy to create a competitive newspaper, as has happened for 200 years of American history.

The situation in D.C. has been mirrored in newspapers in cities across the country, though it’s less noticeable elsewhere. We’ve known about this problem in various forms for around 15 years, and there have been a number of attempted policy interventions to save newspapers. In 2018, then-Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley announced an antitrust investigation into Google. In 2020, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google, a suit which is still ongoing after many procedural delays by the courts. In 2022, the Antitrust Division sued Google along similar lines as Paxton, and won earlier this year. Unfortunately, the remedy phase is still ongoing, and there are likely to be years of appeals.

A different attempt was the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act, a bill sponsored by Amy Klobuchar that allows newspapers to band together and negotiate with platforms like Google and Meta over data and ad revenue, a sort of collective bargaining approach. That bill did have some movement in the Senate, but ultimately failed due to the lobbying of big tech. In California, lawmakers proposed something similar, but Governor Gavin Newsom, operating on behalf of Google, ultimately killed it.

In Australia, a similar law did pass, this law fostered so much revenue for newspapers that the job market for journalists there was buoyant. Google and Meta put $1 billion into the media ecosystem over three years, which those companies then could use to support their search and social media operations. There are problems with the law, and it needs modification, but it has basically kept journalism viable in that country.

Another policy change is the emergence of generative AI. In 2022, big tech platforms, seeing OpenAI’s ChatGPT product, pursued a specific model to commercialize generative artificial intelligence. They began sucking up all journalism and creative content without compensation to journalists. They built AI-powered chatbots who could take what newspapers reported, repackage it, and give it to users. By monetizing the work of others without giving them compensation, these products have undermined the business model underpinning ad-funded journalism. Google’s AI Overviews, which summarize the web on search queries, has crushed web traffic. Here’s the Economist with a viral article and chart published last year.

For companies that sell advertising or subscriptions, lost visitors means lost revenue. “We had a very positive relationship with Google for a long time…They broke the deal,” says Neil Vogel, head of Dotdash Meredith, which owns titles such as People and Food & Wine. Three years ago its sites got more than 60% of their traffic from Google. Now the figure is in the mid-30s. “They are stealing our content to compete with us,” says Mr Vogel. Google has insisted that its use of others’ content is fair. But since it launched its AI overviews, the share of news-related searches resulting in no onward clicks has risen from 56% to 69%, estimates Similarweb.

Generative AI is not just a politically neutral innovation, it’s technology engineered with certain political assumptions in mind, notably that copyright holders have no rights. Plenty of judges are wrestling with copyright as it pertains to large language models. Now-Senator Hawley has a bill to prohibit big tech from using copyrighted works to train AI models without permission from the creator. That bill hasn’t moved. And in the Google search antitrust remedy case, the Antitrust Division asked to allow publishers to opt-out of AI Overviews, but Judge Amit Mehta didn’t listen. The political pressure has forced some deals between AI firms and bigger content producers, but with a lot less value for the content than they should have received.

You might think, and many would, that forcing big tech to license content would make AI non-viable. But I know of at least one AI firm that uses licensed content, and their models can do things that big tech models can’t, and their compute needs are a tiny fraction of the hyperscalers. It turns out, incorporating lots of crap data requires a bloated inefficient approach, while actually working with creators is a far more efficient process. The point, however, isn’t that one policy choice is better than another, it’s that the path of AI development is a political choice that has technological implications. And we chose, as a society, to kill local journalism, just as we are choosing to eliminate cattle ranchers, movie producers, local bankers, independent pharmacists and dentists, and basically anyone who works for a living.

Bezos’s attack on the D.C. community is doing something I thought I’d never see - the liberal class is waking up to oligarchy. Now I don’t want to overstate the dynamic. Take Marty Baron. Like many boomer liberals, Baron is an intelligent fool. He is, for instance, on the board of a Google-backed think tank, the Center for News, Technology, and Innovation, and almost certainly doesn’t realize that his beloved newspapers have been decimated by the entity he currently helps. The fact, however, that even Baron has been forced to reckon with the dangers of the superrich, is meaningful.

Taking a step back, the stakes of our politics are becoming undeniable. Even the rich are becoming afraid of the superrich. Wealthy Hollywood producers are terrified of the Silicon Valley takeover of their livelihood, and the second tier of Wall Street is scared, as the wealth protection industry itself is under attack from the oligarchs who want to automate their servants away. Chris Hayes, a wealthy TV personality, made the point in a viral tweet, saying essentially that Jeff Bezos and billionaires believe that everything that is ours should be theirs.

As Louis Brandeis once said, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can't have both.”

That is a lesson Jeff Bezos is helping to impart to all of us, once again.

Source: BIG by Matt Stoller

Comments

Post a Comment