Quite frankly

Quite frankly

The arrogance of Anthony Fauci, and what it means for the rest of us

Dr. Anthony Fauci has had himself a year (or two).

As 2020 began, he was a senior federal bureaucrat best-known for helping defang the AIDS crisis. A week before, he had turned 79, well past the standard retirement age for government employees - though he controlled a multi-billion research budget and no one was publicly suggesting he step down.

The novel coronavirus changed everything for him.

Within months, practically every American knew his name. People worldwide viewed him as their best hope to defeat Covid. As President Trump fumbled, Fauci’s authority grew.

“How Anthony Fauci Became America’s Doctor,” the New Yorker wrote in April 2020. The nickname stuck.

Once Joe Biden replaced Donald Trump, the title essentially became official. Fauci is now “Chief Medical Advisor to the President” in addition to his day job as head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

He is probably the world’s best-known scientist.

He earned that title the hard way, by giving too many interviews to count. As the Washington Post explained in a glowing July 2020 profile:

At first, as soon as Fauci was anywhere, he was everywhere. The New York Times dubbed him the explainer-in-chief for all things coronavirus, and he did his explaining to Laura Ingraham and Chris Cuomo, in the largest papers and the littlest websites, on the early morning rundowns and the noontime Sunday shows. He showed up to chat with Trevor Noah and Stephen Curry.

The schedule would have been grueling for a person half Fauci’s age - especially since he had to find time between those interviews to, you know, actually track the science around Sars-Cov-2 and vaccine and drug development.

But he managed!

“With all due modesty, I think I’m pretty effective,” Fauci told InStyle. “I certainly am energetic. And I think everybody thinks I’m doing more than an outstanding job.”

With all due modesty… everybody thinks I’m doing more than outstanding job.

As the United States faces the biggest decisions yet of the epidemic - whether to force mRNA vaccines on unwilling Americans, whether to encourage booster shots for the already vaccinated - the way Fauci views himself and his critics deserves a look.

—

To be clear, I’m not writing today about the substance of the choices we and Fauci face.

Nor will I examine the evidence that weeks after Sars-Cov-2 emerged, Fauci appeared worried the virus had leaked from a lab in Wuhan performing the “gain-of-function” research he championed. Those are crucial topics worthy of a deep dive. For now I simply want to look at Fauci’s attitude.

Fauci has always been a skilled courtier. He said as much in a 2014 interview with the Journal of Clinical Investigation:

I think one of the best things I did was realize this is the terrain, so get used to it and get good at it. And I learned some fundamental principles. One of the first things is to understand the relationships between people in power: the Congressmen and -women, the Senators, the chairs of committees, and importantly, the Presidents of the United States. I never in my wildest dreams would have thought that I would become adviser to five separate Presidents.

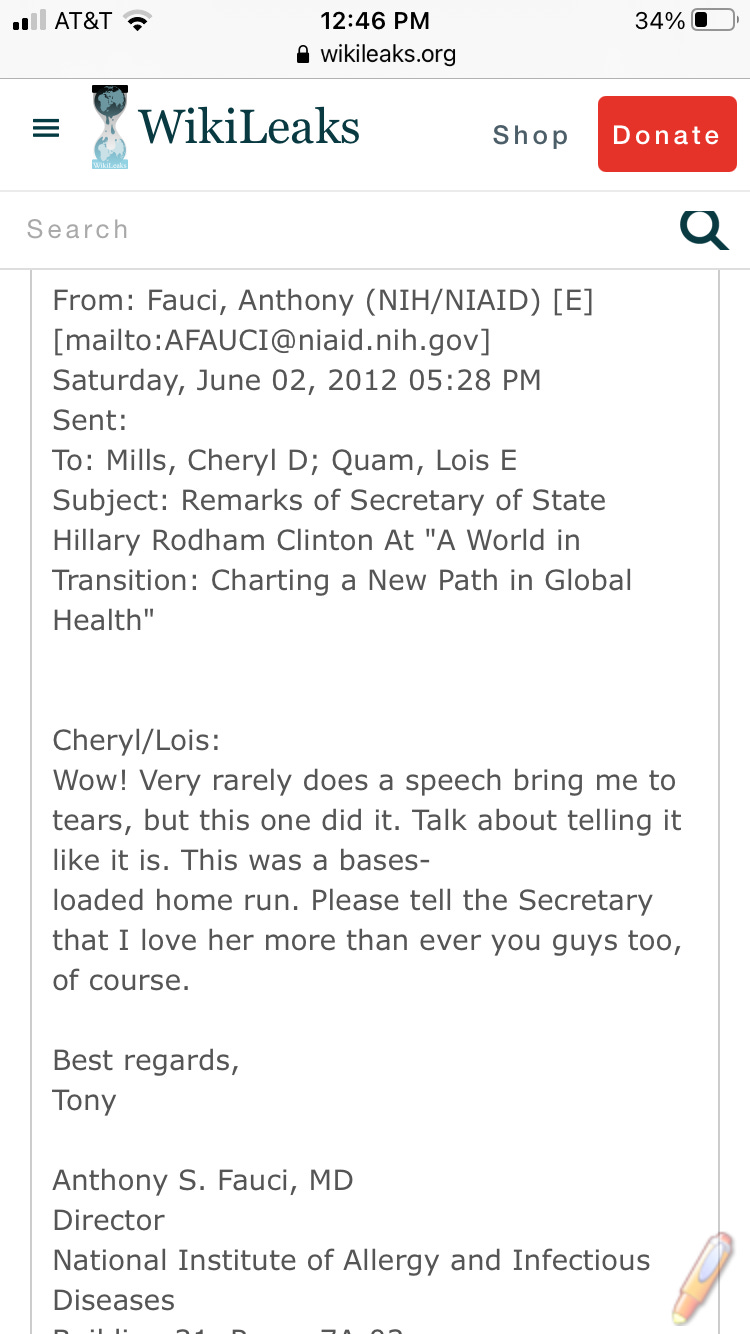

Sometimes, that means making sure powerful people know how much you care about and respect them - and even love them!

But Fauci made sure that those powerful people - and everyone else - understood he was a scientist first. Sometimes he would even offer a visual aid, as the Post’s 2020 profile explained:

“Shalala [Donna Shalala, Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Health and Human Services] often sent Fauci to the Oval Office when Clinton’s aides told her she had an hour with the commander in chief to do with what she wished. When Shalala asked Fauci to speak to the country, she had a special request: ‘Put on your white coat … because people trust the doc.’”

Who was Tony Fauci to argue?

Along the way, though, Fauci developed a healthy self-regard. Maybe he always had it. When President George H.W. Bush asked him to run the entire National Institutes of Health in 1989, Fauci said no. “This is not the time for the general to leave the battlefield to go back to the Pentagon,” he told Science magazine.

—

Woe to anyone who disagreed with him, though.

In August 2020, President Trump named Dr. Scott Atlas as a special adviser on coronavirus. Like Fauci, Atlas is a physician, although he comes from outside the public health establishment. Unlike Fauci, Atlas did not support lockdowns.

Within weeks, Fauci attacked Atlas, telling CNN that Atlas was giving Trump information that was “either taken out of context or actually incorrect.” But Fauci hoped he and Atlas could find common scientific ground, he said:

If I have an issue with someone, I'll try and sit down with them and let them know why I differ with them and see if we can come to some sort of resolution. I mean my differences with Dr. Atlas, I'm always willing to sit down and talk with him.

Which made an interview Fauci gave to Politico in January 2021, after Biden took over, particularly interesting. Asked about Atlas, Fauci responded, “He didn’t undermine me, because I didn’t give a shit about him. I didn’t really care what he said.”

I didn’t give a shit about him.

So much for a sitting down and talking. Or a reasoned conversation about the pros and cons of lockdowns. With the public health establishment and the media on his side, Fauci was untouchable, and he knew it.

Occasionally, if Fauci were challenged hard, his mask would slip even in public. Kentucky senator Rand Paul found this out when he pushed Fauci on whether the NIH had funded “gain-of-function” research in China - research designed to make viruses more dangerous.

“Senator Paul, you do not know what you are talking about, quite frankly,” Fauci answered.

Quite frankly became a Fauci catchphrase of sorts.

Asked in October 2020 about the possibility of reaching widespread immunity against the coronavirus without waiting for a vaccine, he answered, “Quite frankly that is nonsense, and anybody who knows anything about epidemiology will tell you that that is nonsense and very dangerous.”

Anybody who knows anything about epidemiology apparently did not include the epidemiologists who had suggested the possibility.

But Fauci’s most stunning comment came two months ago, in an interview with MSNBC.

“Quite frankly, the attacks on me are attacks on science,” he said. “If you are trying to, you know, get at me as a public health official and a scientist, you're really attacking not only Dr. Anthony Fauci, you're attacking science...”

This level of arrogance would seem almost absurd if the stakes were not so high.

But they are.

The United States desperately needs a full and independent investigation into what Fauci and other officials knew about the risks of gain of function research and whether they worked to steer scientists and reporters away from examining the origins of the virus in 2020. Such an inquiry may turn out to be embarrassing for Fauci, but it should have happened already.

Even more importantly, data from Israel and increasingly the United States show that the mRNA vaccines Fauci championed are far less effective than they seemed months ago.

A rational response to their plunging effectiveness would be - at the least - to stop encouraging their use while scientists investigate why they have stopped working so quickly. Instead Fauci is pressing Americans to take a third mRNA dose in the hope it will work better and longer than the original two.

But no clinical trial data shows a third dose will reduce infections, much less hospitalizations or deaths. And a research preprint released Monday (Aug. 23) in Japan suggests the Delta variant could evolve in a way that could produce vaccine antibody-dependent enhancement, a nightmare scenario.

Figuring out whether this risk is real - and what to do if it is - will require open debate that may include uncomfortable moments for the public health advocates who have pressed these vaccines.

Instead, Tony Fauci has taken the position that questioning him is attacking science.

Unless he changes - or is forced to change - his attitude - we may have a hard time finding the answers we need.

Comments

Post a Comment