Friday Philosophy: How the 'Will to Power' Explains the Tyranny of the 'Experts'

Friday Philosophy: How the 'Will to Power' Explains the Tyranny of the 'Experts'

Scientific 'facts' are never as important as the human drives toward power and success.

I am sure, like me, you are infuriated by the hypocrisy of scientists and politicians in how they choose to apply ‘the science’ in our current moment of crisis.

Masks and lockdowns have zero scientific basis. Yet here we are - asthmatic kids being treated like criminals for not masking up when out of breath:

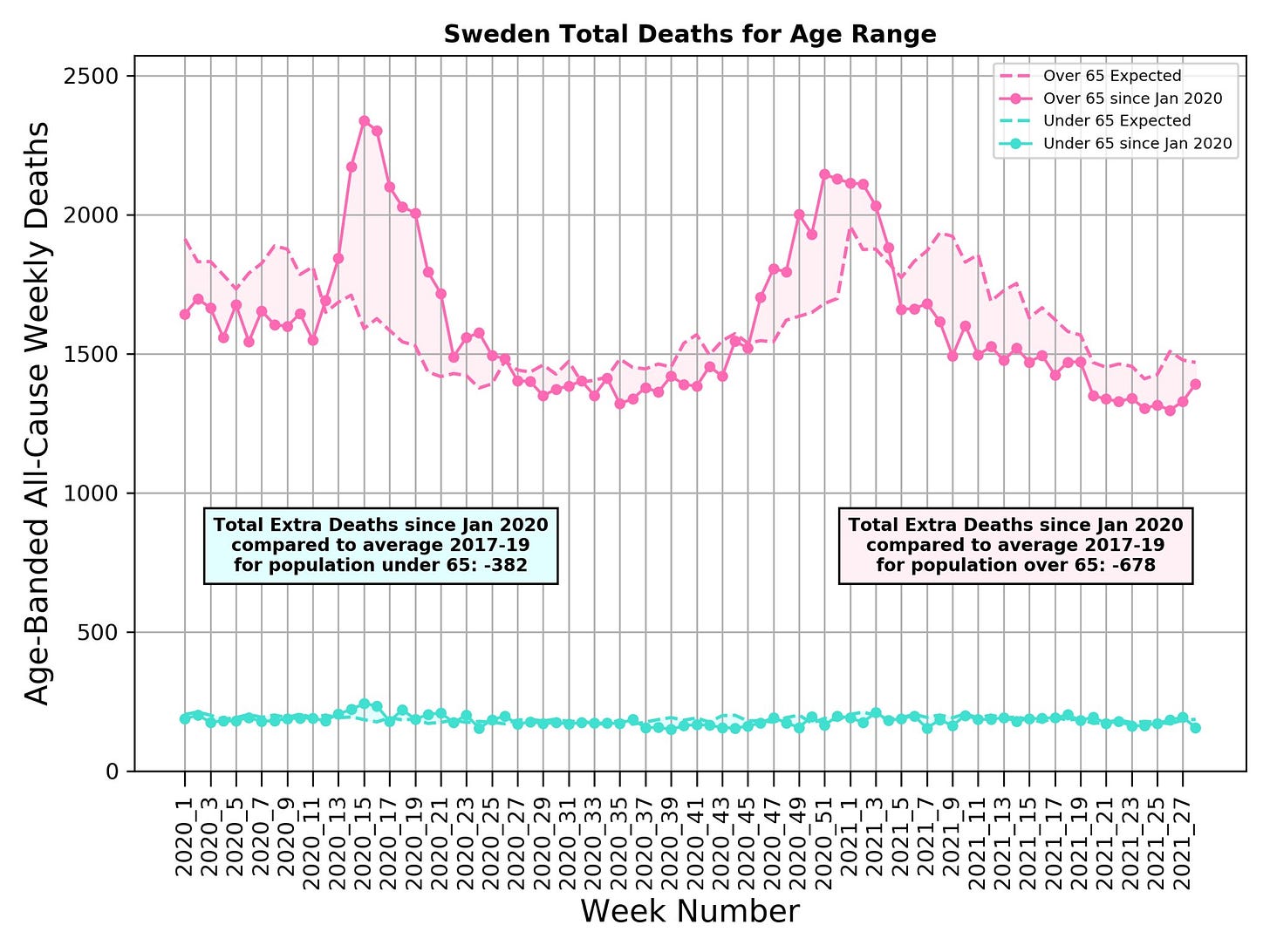

Sweden has no excess death, with no mask or vaccine mandates, yet here we are.

Natural immunity is more powerful than vaccinated immunity (as it has always been for time immemorial as vaccines depend upon natural immunity), yet here we are.

How do we explain this?

I have written many times on this forum that medical science is in the midst of a massive replication crisis. The majority of their studies cannot be replicated with the same findings, ensuring they are practically useless. Yet the media will continue to publicize ‘recent studies’.

(Yes, I do cite studies myself - not because I hold them sacrosanct, but because studies emanating from the scientific complex are useful to demonstrate the hypocrisies of that complex when it decrees revolutionary changes to human life - without basis in their own beloved scriptural studies. For a rare demonstration of that hypocrisy in the media, read this look at studies on masks.)

Why are so many studies basically useless? And why is our new biomedical police state so hypocritical in how it applies their own ‘science’?

I believe we can find the answer in the greatest of modern philosophers, Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche has an unfairly ‘bad’ reputation.

Christians only see him as the thinker behind the famous statement ‘God is dead.’ Liberals think of his ubermensch concept as a forerunner of National Socialism.

I recently wrote a dissertation on Nietzsche, and the truth is far more complex than that.

Nietzsche’s statement that God is dead is less a call to stamp out religion as it is a tragic announcement that Enlightenment Europe has no grounding for morality anymore, and is threatened by a terrible nihilism - a terrible temptation that has two possible outcomes: a belief in nothing but base pleasure and a will toward nothing but conformity and bland collective happiness centered on materialism; or a catastrophic resentment toward all beauty, all greatness and thus a politics of revenge and slaughter. (Both temptations were triumphant in communism and capitalism.)

His ubermensch concept is not a call to merciless Aryan supremacy, but a desire to achieve a kind of eternity and transcendence of one’s life, a sacredness even if one can no longer find God in Enlightenment Europe.

Even his tirades against Christianity are more nuanced than is popularly believed.

The Catholic philosopher, Henri de Lubac, recounted this anecdote concerning Nietzsche, related by his Christian friend, Ida Overbeck:

“Ida Overbeck confided to him that she did not find peace in Christianity and that the idea of God did not seem to her to comprise enough real content. Quite moved, Nietzsche replied to her: ‘You are only saying this in order to come to my own aid. Do not abandon it ever, this idea of God that you have! You possess it unconsciously in yourself…’ … Then he burst into sobs.”

Now that I have hopefully questioned some of the prejudice towards Nietzsche, let us see if we can find any wisdom of his that relates to the crisis of our time.

First of all, the absolute, insane fear of death pervading society, to the extent that we are willing to live in masks, behind screens and plastic, rather than take the very minimal risk of death, is something Nietzsche would have abhorred.

He believed that life can only be justified if it is willing to reach a kind of eternity in which we love our fate and take the risks of an adventurous life. Nietzsche himself was a famous hiker, and he believed that only thoughts experienced at height and outdoors were worth anything.

Second, Nietzsche’s great insight was that our lives are not really motivated by truth and facts, but by the will to power.

We are not primarily scientists or mathematicians. We are humans in a story, first and foremost. And humans are motivated by power.

This power can be decadent or overcoming.

By decadent power, Nietzsche meant power that is motivated by resentment, that is crafty, that seeks power over others to cover up one’s own insecurities.

Healthy power is direct. Its mastery reaches to a level where strength can be turned into kindness, that love is not given simply to score points or show virtue, but is a descent of a grand spirit.

How does this relate to covid?

It does so in two ways.

First of all we imagine that the scientists are above politics, are neutral, and we imbue them with a kind of priestly reverence.

This is a massive mistake.

Nietzsche believed that scientists were just as motivated by power as anybody else. We see that in the replication crisis and in scientific hypocrisy. Clearly the experts are not simply motivated by neutral truth. Otherwise they would apologize for lockdowns which have plunged millions into starvation,

Yes, scientists, like everybody else, can have a healthy drive for power - a power not motivated by the need to impress others or to be a part of an accepted narrative so as to enjoy herd privileges, but instead motivated by attention to craft, to health, and to expressing even uncomfortable truths for the culture at large.

But we have seen the scientific will to power can also be ugly.

Exaggerated death counts, love of publicity, vicious attacks on sceptics (is science not meant to be based on scepticism?), associating oneself with science itself, and the desire to control, even using police powers over children, are examples of an ugly will to power, a decadent will to power, which in itself is a symptom of a society in decay, a society that has lost its hunger and passion to live.

We see this same resentful decadence in the people who post selfies of their vaccinations, who vent about how stupid the masses are not to wear masks, who enjoy a newfound ability to show a strange religious loyalty to public health policy and pharmaceutical companies, to show virtue without any real cost or sacrifice.

Nietzsche, unfortunately, shows no easy way out of the grip of decadent will to power. Instead he proposes that each person can take in the worst of realities, a resentful and flattening society, and somehow sublimate them into an independence of spirit, a disciplining of one’s self toward some kind of greatness.

This is the source of his most famous aphorism, that which does not kill me, only makes me stronger.

It does not, however, often apply to societies and civilizations, which are always liable to commit suicide as they lose faith in themselves and in their own existence.

In the face of a plastic global will to power, we need to find our own healthy will to power, not motivated by revenge and resentment, but by an aristocratic spirit, that can face a nihilistic world but still seek to overcome, and seek this overcoming and victory of health, even without the prospect of success.

For Nietzsche, that meant abandoning German politics and academia, walking high mountains, and writing unpopular books, in a bid to bring about a new epoch in European thought.

Nietzsche would suffer a catastrophic breakdown in the midst of these contradictions. He would not achieve the ubermensch. But he did write something intriguing to those who wonder about the state of his own soul - ‘only where are tombs are there resurrections.’

Western society is a tomb, and who knows, its own death may coincide with the end of all things. But even if we are headed into some kind of dystopian nightmare, the reign of an antichrist, it is not Christian, or even Nietzschean, to despair.

Only where there are tombs are there resurrections.

Comments

Post a Comment