Technological Society and its Discontents

Technological Society and its Discontents

Man, Machine, Managerialism

For centuries -at least- we have heard from many corners a restatement of the idea that civilisation is making people sick. It is a serious objection to the way we live and is one deserving attention. Here follows a treatment of the technological society.

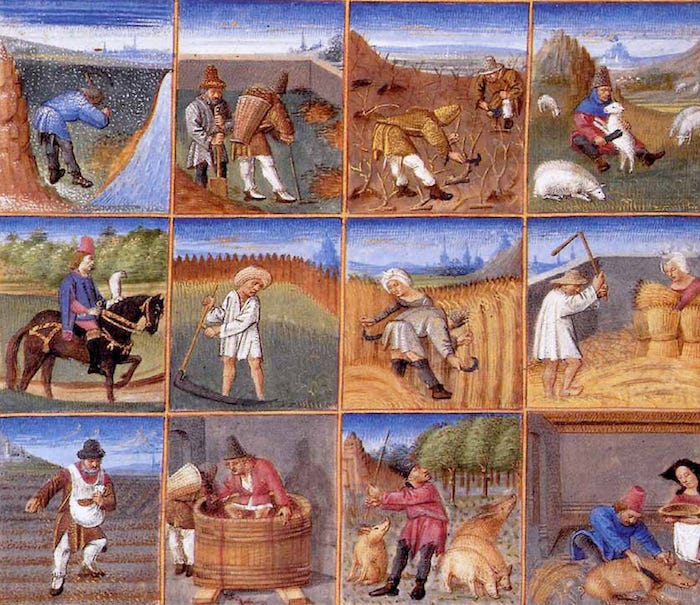

Technology as craft

Timeo Danae et dona ferentes - I fear the Greeks bearing gifts.

The gift of this horse was the ruin of Troy. It was thought to be divine - a gift from the Gods. It was a clever device which destroyed a nation, made by a crafty man.

Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains

The Enlightenment brought us many catastrophic illusions, and the work of Rousseau is one of the most successful. His idea deserves careful treatment because it can resemble the legitimate observation that the structure of our society does indeed make us all ill.

Rousseau said we are unhappy and imprisoned because we have strayed from the state of nature. He was broadly correct, if for the wrong reasons, that cities=bad and rural=good. This however is due to SCALE, not to the inherent evil of sewage systems and paving stones (as he seemed to believe). The concept of SCALE is a considerable idea and will be treated in a later post.

Rousseau believed that Man was in his natural state good, wise and healthy. It is civilisation which poisons him. He argued for a social contract in which we all act naturally for the good of one another. This sense of the Good flowed from Man in an uncorrupted state. It is a view of humanity as essentially and effortlessly virtuous, but poisoned by the man-made. This idea derives from the principle of sufficient reason advanced by Gottfried Leibniz, whose contention that this is the ‘best of all possible worlds’ is known as Leibnizian Optimism. It was soon to be infamous - as Panglossian.

Dr Pangloss

In a devastating revelation, Voltaire revealed that Rousseau, the champion of basic human goodness, had abandoned his five children in an orphanage. Liebniz was clowned upon for his naive justification of evil, which simply represented it as good. Rousseau was similarly concerned with metaphysical waffling which bore no relation to life as it is lived - especially by himself. He believed that men could live according to a general rule arising from their personal conduct. What this would mean in practice is evidenced by his own life. He was ultimately caught in the trap of his own reasoning. This is the fate of Enlightenment thought. It seeks to liberate by forging better chains.

Two ideas of human nature

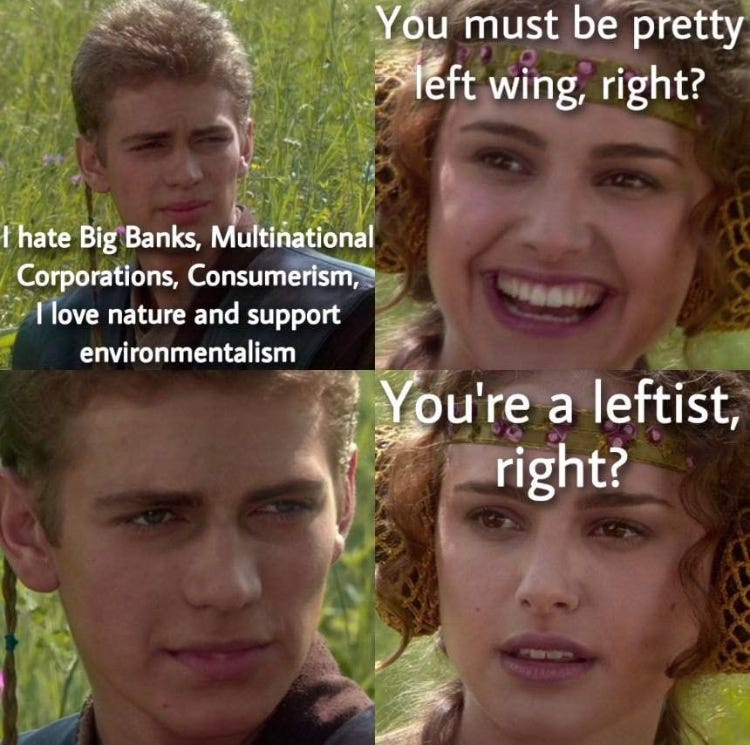

There are two ideas here of human nature - flawed and flawless. If man is flawed then the evils noticed by Voltaire and others are to be expected. If not, he is ruined by something. Perhaps this something is civilisation, if you are Rousseau. Perhaps it is capitalism, if you are a communist. It may be video games, or the obvious poison of pornography.

You do not have to accept that man was perfect at birth to concede there are social ills which weaken and sicken him.

I take the view that we find misbehaviour attractive. Sin is alluring. The gutter beckons us with its gurgling, filthy promise, and we often fall in willingly. This is possible due to free will. Obviously there are social ills which flow from the structure of our economy and the management of what is fondly misrepresented to us as the global village.

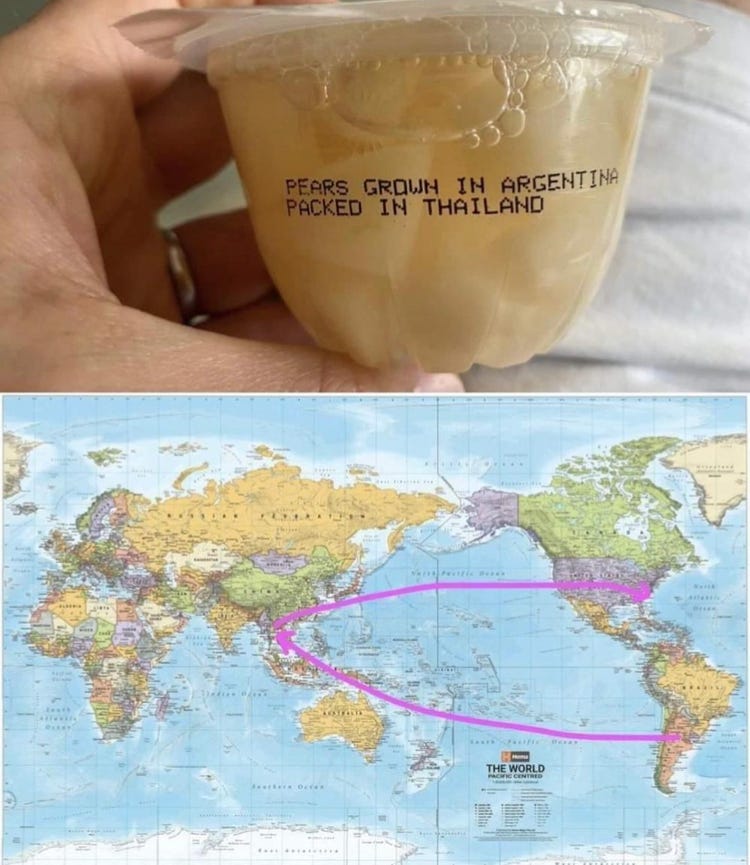

My argument here is not that all technological progress is wrong, nor that it is inherently evil. It is that the machines we have invented to help us are no longer concerned with our welfare. To them we are a resource to be exploited, and it is to their mentality - if that is what we call it - that we must adjust.

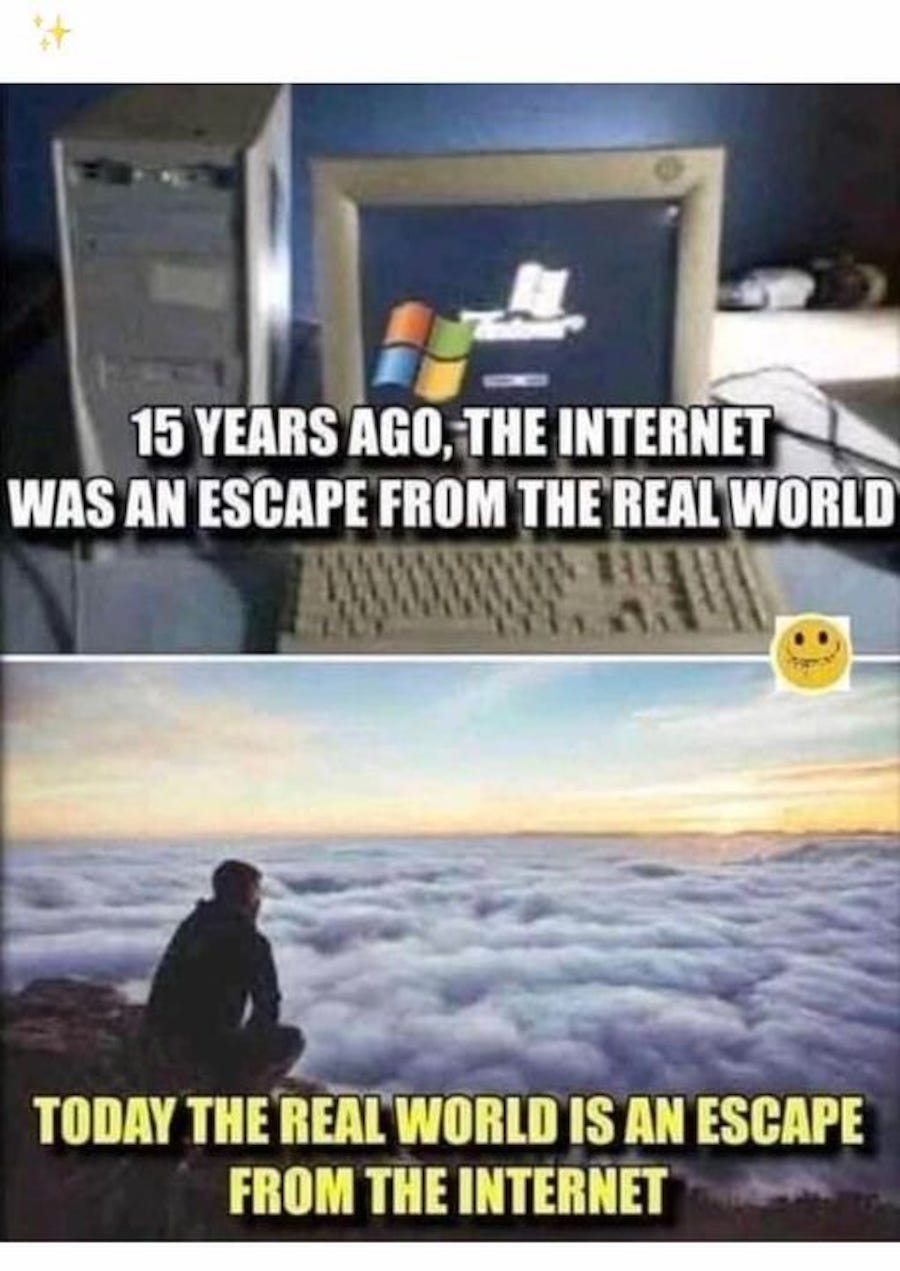

Two types of machine

There are machines of matter and machines of management. The first category includes telecommunications, industrial equipment, gadgets and the like. The second category is the bureaucratic machine. Both forms promised liberation and both initially delivered it. As we shall see, they now serve their own imperatives, and we are less not more free as a result. Further, it is to the machine that we are ourselves calibrated. Mobile phones shape our consciousness, switch on our reward signals, making us all partly virtual beings. This dissolves identity.

The bureaucracies of state and corporation are omnipresent, pervasive as they are distant, tangible but unreachable. They have all developed a kind of immune response to individual people, which becomes apparent at any time you have reason to question or challenge their services.

Health care, public administration, leisure facilities, schooling, degree vendors, policing, the armed forces, fast food franchises, supermarkets, big tech - they are all as alike in the advanced managerialism which renders bureaucracies almost autarkic. That is, they have learned to survive alone, against the countervailing forces of those people they were intended to serve and also of the waning power of the politicians elected to do the same. Bureaucracies serve themselves now. We are incidental to them, important only at scale, as an abstraction.

Mutualism

He said his ideas could be summarised as:

…agricultural-industrial federation. All my political ideas boil down to a similar formula: political federation or decentralization

He thought factories should be run by the workers and that people should trade their goods and services between themselves. He hated usury and wished to abolish the lending of money at interest. He opposed unearned property, and is described as a ‘libertarian socialist’. Maximum freedom, minimal State, cooperation not competition.

Proudhon thought that individual rights were opposed to those of the State, and he insisted that retaining possession of what you truly owned was vital to preventing the State from crushing you. His ideas founded modern anarchism, saying

whoever lays his hand on me to govern me is a usurper and tyrant, and I declare him my enemy

and his work is interesting for its treatment of the condition of humanity under the industrialising machine. His answer was to propose a human scale society, which is the reason he is mentioned here.

In fact, he was not an anarchist and in later life argued for a state authority compatible with personal liberty to balance both. He was, in my view, more of a radical conservative than a man of the Left, being untrustworthy of the State but equally concerned with the limits of human goodness. The basis of freedom for him was ‘economic right’ - ownership - and he abhorred the idea of state property in common.

Ned Ludd - Rage against the Machines

From 1851 to 1856 Ned Ludd would meet in a natural cavern near Buxton, in Derbyshire, called ‘Ludd’s Church’. Here he would galvanise his fellow workers against the use of machinery to exploit and degrade the lives of ordinary people.

‘Luddite’ is a derogatory term these days, delivered with a sneer. It denotes superiority in the sneerer, belittling with this label anyone who is unenthusiastic about some or all of modern technology. To most people who use it, it means something like ‘You are ignorant and stupid - but I am not.”

In fact, Ned Ludd did not indiscriminately smash machines, and he did not only attack new ones. His movement was focused on the machines used by owners who would endanger or exploit their workers. Luddites wanted technology to serve humanity, not the reverse. The efficacy of modern propaganda explains how this noble impulse has now become a term of derision.

Back to the Planet

Primitivism was one outcome of the anarchist movement, which heavily influences - through ‘Green Anarchism’ - the environmental activism of today.

This idea must be mentioned as it is the logical progression of the belief that all technology is evil. Primitivism rejects both types of machine.

The name suggests the ideology. To escape the machines we must go back in time, avoid modern food and technology, live in wooden houses made of natural materials and reject everything else. Mainly vegan, completely misanthropic, the Primmies (as they are known) accept openly that their system would lead to a huge collapse in the human population, reducing it to around one billion globally.

There is little mention as to how this peaceful transition to paradise may be achieved. Yet the argument is nevertheless compelling when we witness oceans awash with plastic, microfibres in our bodies and in our drinking water, the replacement of beauty with faceless anti-architecture. High rise, low life.

It is appealing to live off grid and if you can do it, consider how your social and family bonds would fare if you were to do so. If you can maintain them this is probably optimal. If not, no amount of home composting will prevent you from the danger of degrading personally. I have lived alone outside and nature is indifferent. Perhaps you have the character for it.

Earth First! (Man second?)

The tension between man and machine is perpetual. A kind of resolution is offered in the idea that we are in fact the problem, and that the planet deserves to be rescued from us all.

Earth First! was a samizdat group (communicating through privately printed newsletters) whose main activity was to destroy industrial machinery and sabotage logging, development, engineering and construction works.

Man could reignite his humanity by direct action - directly attacking the machines which he saw as the enemy of Mother Earth. Of course it is easy to be moved by natural beauty, and anyone indifferent to it is handicapped or incomplete. To be motivated to destroy life in its defence, however, is a far darker impulse. It was through contact with Earth First! that the most notorious enemy of the machine was moved to action.

Industrial Society and its Future

This is the title of Theodore Kaczynski’s infamous book. Known as the ‘Unabomber Manifesto’, he wrote this over a twenty year period spent living in a small shack. He wished to be left alone, but the overflight of fighter planes and the encroachment of commercial logging propelled him to revenge. He had no wider goal than vengeance, yet his writings are startlingly prescient.

The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in “advanced” countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world.

“Theodore” means “gift from God”. He would send some of his own gifts through the post, mailing bombs to universities and public administrators, before posting his manifesto to the national press. He declared war on machines and The Machine alike, and he has written some of the most striking prose on the way both aspects of technology have altered human life. His brother recognised his writing style and gave him up, ending the longest manhunt in US history. He is now in prison.

Ted Kaczysnki remains an optimist:

Never lose hope, be persistent and stubborn and never give up. There are many instances in history where apparent losers suddenly turn out to be winners unexpectedly, so you should never conclude all hope is lost.

Neo-Luddism

Theodore Roszak wrote in 1994 about ‘data glut’ - how the machine mind was overwhelming ours, and what the computer world would mean for the human.

Where Sisyphus was condemned eternally to roll a rock up a hill, only to see it roll back down, his endless torment has been transformed by technology. The condition of man, according to Roszak, is to be connected to the machine which rolls the rock for him. The machines work for us, but at what price? This is not a liberating symbiosis.

Today, new technologies are being used to alter our lives, societies and working conditions no less profoundly than mechanical looms were used to transform those of the original Luddites.

A neo-Luddite movement would understand no technology is sacred in itself, but is only worthwhile insofar as it benefits society. It would confront the harms done by digital capitalism and seek to address them by giving people more power over the technological systems that structure their lives.

Jacques Ellul and The Technological Society

The only writer with more to say on the matter, and what he has to say is essential reading, is Jacques Ellul. He is a Christian and his work influenced the infamous Unabomber, most of it being written between the 1940s and 1960s.

La Technique

This means that the machine supplants the mind, rendering our culture and the people who make it mechanistic. Both types of machine combine to make of man a third - a mechanical product incapable of anything other than fitting in. Apart, and a part.

Comments

Post a Comment