State Power

State Power

And the temptation of anarchism

Image ©Nieuw

I do understand anarchists. Even more so rich anarchists. In a way, a First-World anarchist is like someone who only knew an abusive father, and ends up rejecting the very concept of family. If I lived in a place where all laws a Modern state tries to promulgate were enforced, the anarchist temptation would be indeed strong. Fortunately, I live in a country whose language has no expression for “law enforcement”, and where laws can “stick” (that is, be accepted and obeyed) or not. Most of them don’t, and absolutely nobody in Brazil would ever consider the possibility of mistaking mere State-promulgated laws for moral precepts.

The problem, though, is not laws by themselves, but the whole package: the function of the State, its powers, its limits if any, what Law (or a law) happens to be, and so on. As always, there is a long story; a quite big chunk of History leading to the present situation. That’s the story I’ll try to tell here.

Laws promulgated by the State (by a personal ruler, in fact, as there were no impersonal States yet) were something quite rare anywhere 500 years ago. People were expected to do what everybody else does and refrain from doing what other people didn’t, and that is it. In a way, this notion persists everywhere; police officers, for instance, tend to see criminals and troublemakers in general not precisely as law-breakers, but rather as people who do stuff decent people wouldn’t. “I don’t go around stealing stuff; why does he?! This low-life scumbag’s place is in jail.”

That is what Anglo legal systems tried to preserve with the notion of common-law rule; hard cases would be solved by finding a previous case that looked more or less alike, and then stretching the precedent decision sotoover the new, seemingly related, situation. It worked well for small tightly-knit communities, but when increasingly big societies tried to rule themselves that way, things started going downhill. After all, what is obvious in a certain place and social group can pretty well sound absurd in another place, and there is nothing to prevent both from being within the same legal system.

The other approach for a legal system is the Roman, created with a vast Empire, of widely different people and cultures, in mind. In it, there is no place for common law: everything one is forbidden to do is written down, and whatever is not forbidden is allowed. That’s how judicial systems work in most of the world. One thing some people don’t realize about it, though, is that in a Roman Law system every judge is in practice quite free to interpret the written law his own way. It is a bit like the American Supreme Court’s freedom of movement around the Constitution: the basic text is the same, but not all Supreme Courts are the same, and what one found in the Constitution is not at all seen by another.

Thus the law, in the Roman system, ends up being not at all something to be obeyed literally, even if such literalness were possible. Laws are guidelines, not moral obligations, and custom has much to do with how (or whether) a certain law is understood and accepted by society in general. On the other hand, in the last two hundred and some years, as Modern society became even crazier, there has been a kind of revolution within legal systems everywhere (and in legal theory as well, of course). Bureaucracies started trying to grant themselves more power by treating written law as if it were nothing less than divine. That’s called “positivism”, as promulgated laws are called “positive law”, in a contrast to customary law. Tommaso Beccaria, the Italian legal theorist, once wrote that a trial should be “the perfect syllogism”, in which the text of the law would be the major premise, the actions of the defendant the minor premise, and the sentence the impersonal consequence. Quite clueless about the ways of the world, the young brat; no wonder, as he was 26 when he wrote “On Crimes and Punishments”, his most important work.

Anyway, in his time, mistaking printed text for divinity had already had a couple of centuries’ history. The present theory of the all-powerful State comes from this peculiar kind of madness, by the way. When the twilight of Western Civilization was started by a monk hammering a piece of paper onto a church door (on Halloween, no less!), there were very strong social pressures brewing all over Northern Europe. Friar Martin Luther’s creation of a brand-new religion with Islamic overtones was not a cause, but a consequence, of his hammering away. He just wanted to challenge a guy who was in his neighborhood fund-raising for the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica (in Rome) to debate him on the fundraiser’s very questionable marketing tricks. All Hallows’ Eve was the perfect time for nailing his propositions to that particular church’s door, as the very next day the largest exposition of sacred relics in all of Northern Europe would be held there. People would be coming from hundreds of miles around, and word of the challenge would certainly get to the peddler.

Friar Martin, though, was a professor of Sacred Scripture; therefore, he had indeed read all of it at least once. The guy who he was challenging, on the other hand, would probably not know more than what was read in the liturgy, even if he had some formal theological training. After all, Peter Lombard’s Sentences – not Scripture, or Patristics, or Liturgy… – were the main focus of higher theological studies at the time. Hence, to make it easier for himself, Fr. Martin came up with a rule for the debate: all and any arguments should be drawn from the Scriptures. Not very fair.

As things started getting hot around what was at first a legitimate challenge, Luther doubled down on his Scripture-only idea, eventually using what began as a small debate trick to turn Christendom upside-down and basically destroy European society by the creation of an alternative reality. After all, religion was then, and in fact still is, the very form of reality for both society and individuals. Religion – be it Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, or modern Atheism-cum-Scientism – is the source of the lens through with we see, as of the logic with which we interpret, the world around us. At that time, in Europe, religion meant one thing, and one thing only, everywhere. Not only did its moral tenets form the framework of acceptable behavior, but religious time – the liturgical calendar – gave people the very notion of time; religious practices – for instance, pilgrimages such as the one that lead to that particular church on All Hallows – were essentially universal and shared by all; religious authority was the basis of civil authority, and so on.

The sentence above does not mean a king was held to be a proxy for God. Quite the opposite, in fact. It means any ruler’s work could and should be checked against what was by then universally accepted as coming from God, and he would rule as a representative of the people. Not God’s: the people’s. Vox populi vox Dei: the voice of the people is God’s voice, and it was more often than not the people’s view of what was right and what was wrong, within the context of an absolutely unanimous religious consent, that would keep or depose kings and princes. A ruler’s authority, thus, depended on how he used his – quite small – authority. He had indeed the power to pass some positive laws, but the list of requisites was quite vast; among other things, he could not pass a law that was not useful, or that went against established custom. His rule in society was that of, say, an old patriarch who will not tell his children and grandchildren how to rule their own homes, but whose authority would be respected to settle a dispute between some of them. Moreover, all of his authority came from two-way personal commitments, in which he would have to protect each one of the people who lived in “his” territories, and they would have to feed him and his minuscule military. He was as much a servant of the land as the lowest serf, as none of them could abandon the territory and both had to serve it and its people, each in his own way.

But there was already a very ugly, fat, and hairy fly trapped in the ointment of society by then: money. More specifically, the fact that there was an increasing presence of money in society, but society had no place for it. According to the Law – that is, to custom – one could either be born a warrior or an agriculturalist, and the only real career choice one had was whether to join the clergy (that took from both). Money made no difference: a wealthy warrior was still supposed to be a warrior, risking his neck for others, and a rich agriculturalist was still supposed to till the earth with his own hands. On could not buy or sell land, though, and all the money in the world could not change a warrior into an agriculturalist, or vice-versa.

But for the last few centuries commerce had started making some people rich. Most of them came from agriculturalist families. There was no place for the rich in society, but they managed to carve one for themselves by using their money to the benefit of the military. It’s not a new thing, you see; in fact, some of those people kept doing it up to our days. The premier weapons manufacturer for Germany in both world wars was Krupp, a family-owned conglomerate that started around that time as a family business.

Before the rich guys arrived in town, there was no town. There were castles, with moats but unfortunately no dragons, and land. When there was a war, the civilians would get into the castle and the military out, but in regular times it was the opposite. Now there was something one could do with money, and the new rich started to fund larger and larger walls around the initial castle walls, and in turn, got to build themselves houses and shops inside the new walls.

The name for those commercial towns that developed between the original and the new and larger castle walls was “Bourg” (or “burg”), and its inhabitants became known as the “bourgeoisie”. Understandably – that’s human nature; complaints shall be addressed to Adam and Eve, on counter number one –, the military and the bourgeoisie would often get quite cozy, to the detriment of the poor folk still outside them walls. By Luther’s time, peasants’ revolts were starting to be common everywhere, but the nobles (or “gentle”, or – as I have been calling them, “the military”) had their hands tied by that nasty obeying-God business. Luther’s revolution gave them a way out.

More than that: he installed himself as the new religious authority, one that would tell princes who asked him how to deal with those revolting peasants to “kill them like dogs”. One hand washes the other, though, and that’s what happened when the former monk found out that substituting the daughter (Scripture) for the Mother Church would not make his own reading of Scripture automatically accepted by everybody who liked his new “Sola Scriptura” gimmick. That “killing like dogs” things was extended to all sects that would not join his new State-approved (or rather local-ruler-approved, hundreds of times over; States were quite small and unimportant still, and – most of all – power was 100% personal: the State was its king) Lutheran Church. That is why, by the way, all Protestant denominations nowadays can trace their institutional and theological lineages back to one or two of the three State-approved Protestant sects of the XVIth Century: Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican. All other options initially stemming from Sola Scriptura were literally eliminated. Killed like dogs.

In a way, something quite similar had already happened a few centuries earlier, when the Gnostic sect of the Cathars rose in present-day Southern France. As becoming a Cathar supposedly freed one from all previous commitments and obligations, and the personal obligations and commitments that issued from formal vows were the basis of social order, people would get so mad at Cathars that they started killing them. Appointing oneself jury, judge and executioner, though, was a big no-no for the Church, and that’s how the Inquisition was born to free the falsely accused. But that’s another story, for another time.

Southern France in the time of the Cathar troubles was the center of the world; Northern Europe in Luther’s time was the boondocks. That’s how the new religion got itself time enough to grow a critical mass and thus survive much longer than Catharism. Calvinism – directly supported by the bourgeoisie of Geneva, with no noble middlemen – was by then mainly a local phenomenon, which survived because of both the complete chaos in the North and Switzerland's lack of importance at the time. The fact that the Swiss were so fierce everybody wanted to hire them as mercenaries didn’t hurt, either.

So the European Wars of Religion started, and for generations upon generations, Europe became a vast battlefield where followers of the Old and the New Religion tried to get the upper hand in order to free the others from the yoke of their horrible heresies and superstitions. Very bad times indeed.

The “solution” for all that came with the Treaty of Westphalia, a hundred years of bloodshed later. It can be summed as cujus regio eius religio, that is, literally, whose king’s his religion: each small ruler’s religion would be imposed on all of his subjects. In other words, while before the Lutheran revolution everybody agreed on what God wanted a government to do, and his authority rested on his conformity to that common view, after Westphalia each local ruler gained the authority to decide on his own what would be God’s truth. Kings were thus in fact placed above God, being granted the right to judge whether what had always been held by everybody everywhere as Divine Revelation was or not true.

That is what paved the way for all that ugly “divine right” absolutist stuff. Still, it’s funny to use the (technical) term “absolutism”, as the powers of a Louis XVI were so much less absolute than those of any bureaucratic busybody of our days. Having been freed from all higher allegiance, check, or balance, anyway, absolutists could indeed be quite annoying. I wholeheartedly understand how American colonists felt about the British monarchs, especially when one thinks that almost all British American colonies started as places of refuge for people fleeing some kind of religious persecution at the hands of whoever was in charge of Westminster at the time.

As a side-note, we did have it easy in the Iberian Peninsula. The Moors (Muslim invaders) had just been expelled, and nobody had time for New Religion nonsense. As a matter of fact, the Spanish and Portuguese discovery and colonization of present Latin America were then seen as part of the struggle to liberate the Christian lands held by Islam. Columbus was trying to find a way to get to Jerusalem “from behind”, and the Portuguese wanted to cut Muslim traders off the Indian trade so as to prevent them from financing the Muslim defense of Northern Africa. America was just in the way, but the combination of blood-curling large-scale-human-sacrificing devil worship to be fought (who wouldn’t?!) and gold to be sent home made it a quite serendipitous “obstacle”.

Anyway, the next logical step happened a century later (things usually get around a century to be fully digested in geopolitics), when the absolute king was replaced by the absolute “People” (the imaginary collective of real-life persons), whose supposed self-ruling powers were obviously “relinquished” from the start to the absolute State. And thus the Modern State was born.

While a pre-Modern king was a person who swore to protect each and every one of the persons in his kingdom, the State is impersonal and deals with vast multitudes, not with individual people. While that king was held to a previously-existing common view of right and wrong and had very limited powers, the State’s might ends up making right. In fact, not only is the State established according to a legal framework it wrote itself (its “Constitution”) and can amend or even replace at will, but it also believes it shall have a monopoly on violence, nothing less.

The universalist claims of Modern “reason”, moreover, tend to deny the individual person’s very being even while theoretically affirming it, as was the case in the American version of the same Modern revolution. There was no personal commitment, no personal vow of loyalty exchanged between ruler and ruled, only a quite artificial set of restraints on the power of the State. And even those came as an afterthought, in the Bill of Rights, which mainly restrains the power of the central State while keeping it in the hands of individual federated States. The “individual” person is presupposed to be almost interchangeable with all other individuals, having no direct and personal relationship with the person in charge – be him a Washington or a Biden –, the one whom he would theoretically have ceded his personal autonomy to. The Modern individual only exists as a part of the People, and “We the People” always ends up being a bunch of rich guys secluded in a locked room talking among themselves.

The State, having absorbed the power supposedly surrendered as a whole by “the People”, is even more absolute, much more absolute, than any crazy English or French king. After all, while an absolutist king or queen could be oblivious to the real life of “his” people to the point of honestly believing that “eating cake” could be a solution when there was no bread, a modern State had endless eyes. Nowadays, with all the technology a State can turn into its service, its problem is not ignoring what a lack of bread truly means, but rather parsing all the too-vast incoming flux of raw data. It does hear every single word spoken around every single cellphone, but it has to find out what is worth listening to. It sees everyone who walks in front of every camera, but it has to find out whom to watch. And so on.

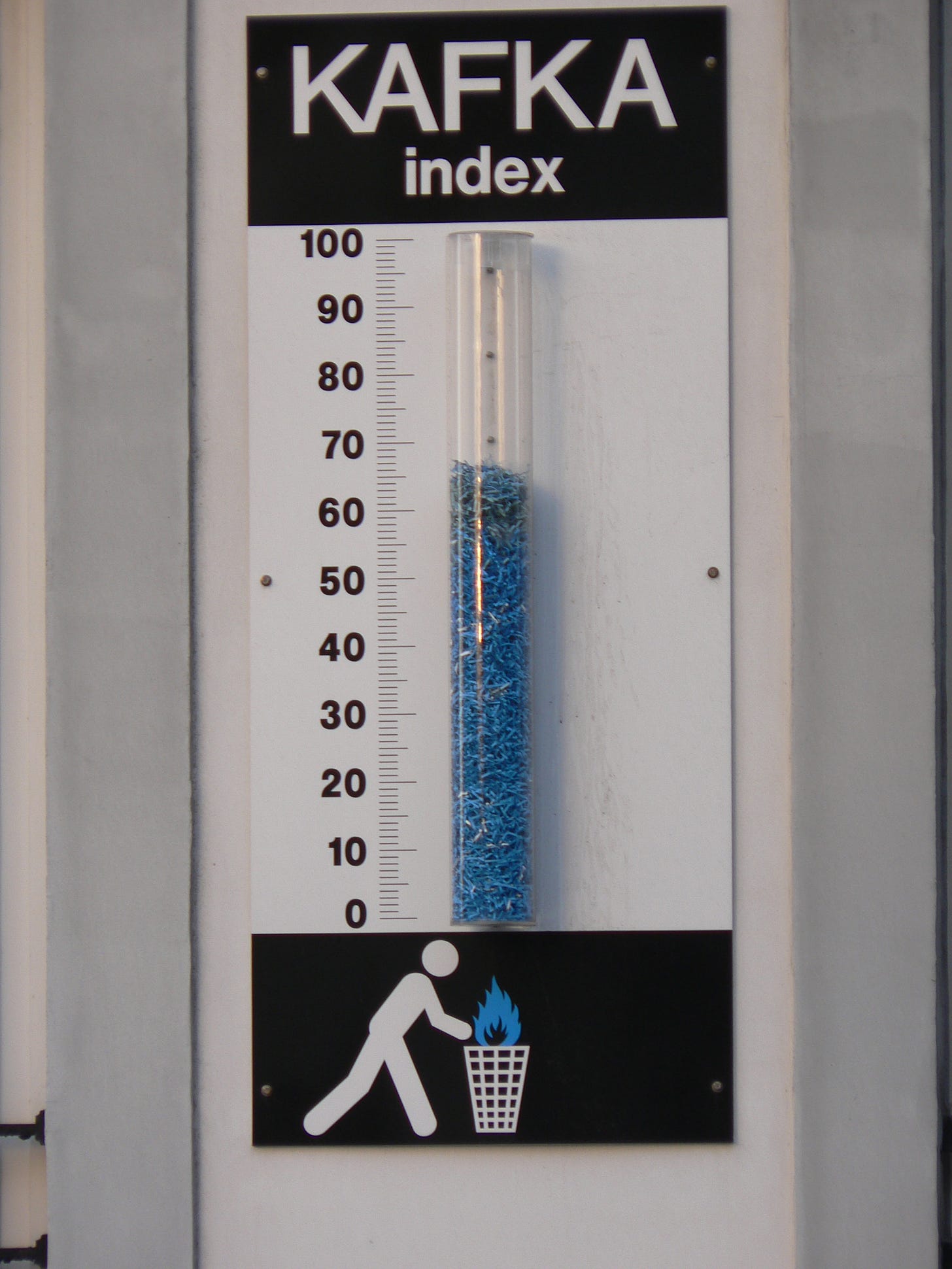

In what used to be called the First World (nowadays it goes by the ironic nickname “the collective West”), to make it a lot worse, State machinery tends to work. Every silly and useless law – which to Medieval legal philosophy would not be a law at all – is indeed enforced; most taxes are paid; most public schools do a rather good job of indoctrinating the poor kids; and – most crucially – not only is State-promulgated law seen as a moral minimum but State-centered mechanisms of conflict-resolution are widely used, spontaneously, by regular folk.

I remember when a Brazilian friend in Paris told another lady she worked with about the trouble her son had been giving her, and the helpfully Modern French lady gave her a toll-free number for the City social services to call. My friend was shocked, as it would never have crossed her mind to put her kid into the hands of City bureaucrats for something that was obviously her own problem. She had vied for a few warm words, perhaps a shoulder to cry on, or even some child-raising tips from her friend; for her, it was a very cold shower to be sent to the bureaucrats.

But when people are used to it, and – much worse – State bureaucracies tend to do most of what they advertise, State power can only grow and grow. It is much easier to find people who do drive without a license in Brazil than in the USA, for instance. After all, even if in the USA people hold the DMV to be the apex of malfunctioning bureaucracy, one does not need to spend more than a couple of hours there to get a driver’s license. In Brazil, it is a months-long process, and everybody needs to go through the same hoops (including tens of hours of mandatory classes, both theoretical and in specially-prepared cars with two sets of pedals) to get that useless piece of paper, that talisman whose only function is to make cops let one go in peace. Getting a driver’s license in Brazil costs a tad more than what one earns for a couple of months’ work in a full-time minimum-wage job, and the minimum age to start the long driver-license-getting process is eighteen. Yet, it’s not that hard to lose it and be forced to redo the whole shebang, as traffic tickets come with “points”, and reaching a certain number of them (two DUY tickets would do it) means losing one’s license and having to restart the whole process. During one’s first year of licensed driving, any traffic ticket is enough to make one lose the precious talisman.

Countries that are not thoroughly Modern – essentially everywhere on Earth except for the former First World – tend to be like that. It is easy to understand why people won’t trust the government; not in an ideological sense, as an Anarcho-Capitalist won’t for a matter of principle, but by experience. The great Theodore Dalrymple (whose name I once spotted together with mine on the same “contents” page of The European Conservative magazine; I got there, Momma, I got there!) once wrote he preferred the Italian (Third-Worldly) bureaucracy to the British one, as one could always bribe an Italian employee to get something done, while in Britain one would be arrested for suggesting it. I go even further: no Italian, Brazilian, Indian, Cambodian, Ukrainian, Persian, or Namibian will ever consider the possibility that obeying some silly law would be morally required of him. None of us would mistake the State for organized society, or even consider the ludicrous possibility that one would somehow need to have a government-issued “license” to cut hair, fish dinner, whatever.

On less-civilized lands, though, that fell prey to Modernity early and whose populations fully swallowed Modern thinking, these are common errors. The only alternative would seem to be embracing anarchism, and together with it the whole panoply of ideologically-derived supposed alternatives to the Modern State. I understand the poor people who fall for it. I probably would, too, if that was the only State I knew. It is just another form — perhaps the strongest yet — of tyranny, that old enemy of man.

Comments

Post a Comment