The Global Energy Crunch

If we insist on doing the transition the hard, slow, costly way rather than the easy, fast, cheap way, it's going to be a needlessly arduous, soul-crushing slog.

Let's cover a few common-sense points and ask a few questions about the Global Energy Crunch. Let's start with the high-tech, super-costly solutions that many promote as the surefire source of abundant, affordable energy: thorium reactors, mini/modular-reactors, clean coal plants and fusion.

Every one of these may turn out to be a solution, but in the here and now they take many years to build and huge sums of money. Full-scale functioning examples of these technologies do not yet exist. Various prototypes are in development, but the timelines are long and uncertain.

For example, one modular nuclear reactor design recently gained approval, and the first prototype will hopefully be ready for testing in 2030. As for when we can expect the first full-scale modular nuclear reactor to start producing electricity, nobody knows. How many units can be manufactured per year is also unknown. Any practical guess is decades.

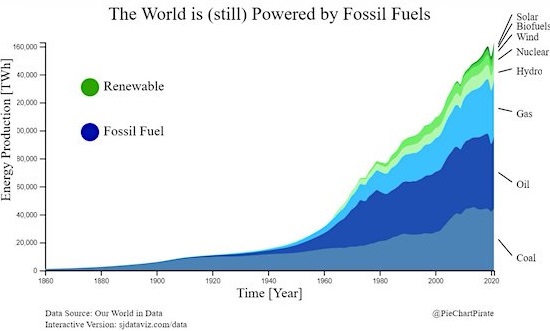

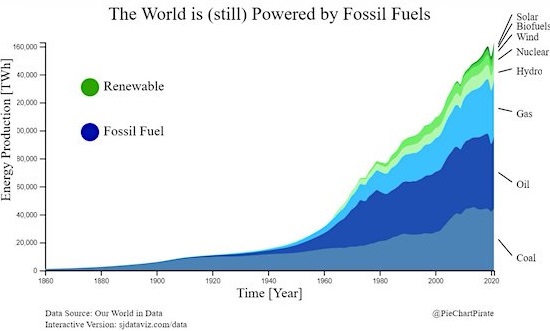

Nuclear reactors are costly to build, regardless of their fuel cycle. Cost and time over-runs are the norm. Five years becomes nine years and $1 billion becomes $3 billion. New technologies are especially prone to over-runs. There are about 440 functioning nuclear reactors on the planet and about 55 under construction in 19 countries. The existing reactors supply about 10% of global electricity--in other words, a fraction of total energy consumption.

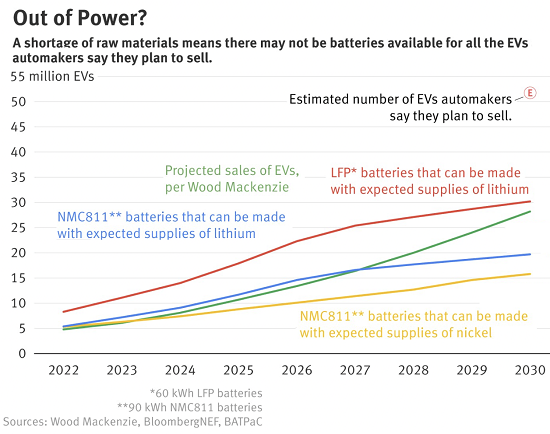

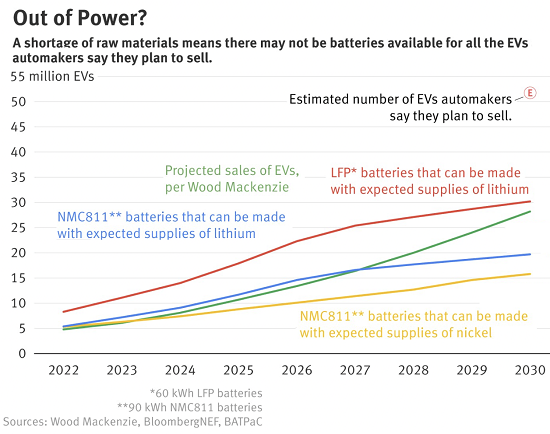

As for everyone's favorite solution, the so-called renewables of wind/solar--actually replaceables--we all know the problem: they're intermittent. So you need a second power generation system to fill the gaps when the sun goes down and the wind dies. As for batteries-- even mega-batteries only hold a tiny percentage of total energy consumption. And it's already clear that there aren't enough minerals to build hundreds of millions of high-tech batteries, which by the way, are also replaceable, i.e. must be replaced every decade or so. (See chart below.)

Common-sense suggests it is folly to shut down existing energy sources until a replacement system is up and running. Yet that seems to be official policy in many places. The idea that getting rid of undesirable energy sources will magically create desirable energy sources is delusional, yet that idea is apparently quite compelling.

Maintaining two energy generation systems--one intermittent and one for backup--is inherently more expensive than having one system. Whether the backup is battery or another energy source (or some of both), it doesn't matter: the cost is greater regardless of the type of backup.

The global energy crunch is real and has no easy, cheap, quick fix. That doesn't mean we're powerless (heh).

Let's ask a few questions of the planet's largest energy consumers: Europe, North America, China and Japan.

1. What percentage of habitable structures are well-insulated or super-insulated to minimize the need for heating / cooling?

2. What percentage of habitable structures have geothermal heat pumps (GHPs) that use the ambient temperature of the Earth to reduce energy consumption?

3. How many empty rooms / spaces in these regions are heated / cooled?

4. How many of the millions of vehicles that are stuck in traffic jams are single-occupant?

You see where this is leading: conservation is the fastest, lowest-cost, lowest-technology way to reduce energy consumption by reducing waste. Rather than invest in universal conservation and incentives to reduce wasteful behaviors (heating empty spaces 24/7, etc.), we've squandered decades and trillions of dollars, yuan, yen and euros on bridges to nowhere, wars of choice, speculative excess, virtue-signaling and the mindless consumption of the waste is growth Landfill Economy.

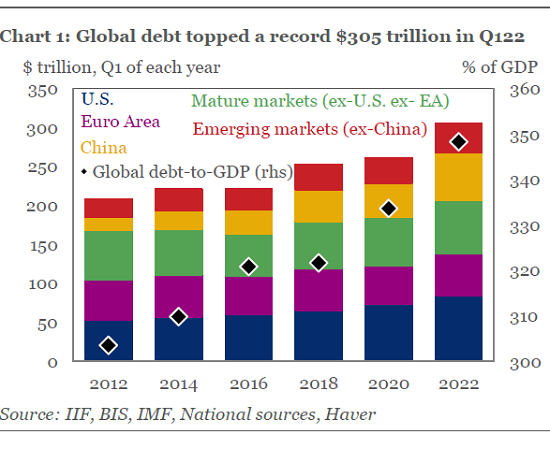

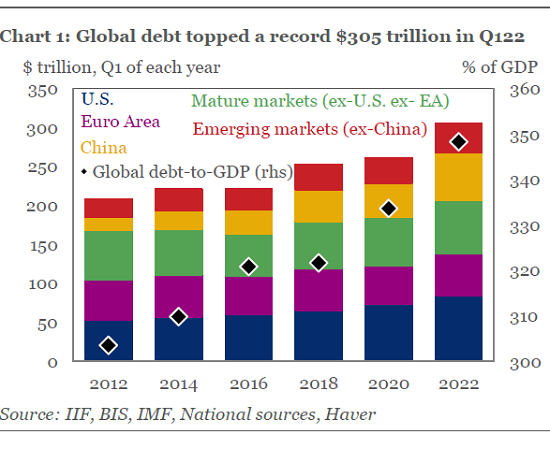

We've squandered trillions that were borrowed and now we have to pay interest on the wasted money.

Many solutions are solely behavioral and require no new infrastructure at all. For example, everyone driving themselves to the city center could stop at a bus stop or equivalent gathering place and pick up three other commuters. Tollways could be reprogrammed to reward vehicles with four passengers.

There are many such behavioral solutions that conserve energy on a mass scale. For some mysterious reason, we seem collectively enamored of high-tech solutions that demand decades and trillions of dollars rather than solutions that are within reach.

Waste is not growth. This is the central delusion of the modern economic mindset and the global economy. Eliminating glaringly obvious waste and using basic technologies (geothermal heat exchange, insulation) are the common-sense first steps to the goal of maintaining energy supplies at affordable levels.

The technologies to radically reduce waste have been around since the late 1970s / early 1980s. Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) (Wikipedia):

By 1978, experimental physicist Amory Lovins had published many books, consulted widely, and was active in energy affairs in some fifteen countries as synthesist and lobbyist. Lovins is a main proponent of the soft energy path.

At RMI's headquarters the south-facing building complex is so energy-efficient that, even with local -40 °F (-40 °C) winter temperatures, the building interiors can maintain a comfortable temperature solely from the sunlight admitted plus the body heat of the people who work there. The environment can actually nurture semi-tropical and tropical indoor plants.

Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI)

If we insist on doing the transition the hard, slow, costly way rather than the easy, fast, cheap way, it's going to be a needlessly arduous, soul-crushing slog. Perhaps we need some uncommon sense since common sense appears to be so scarce.

Let's cover a few common-sense points and ask a few questions about the Global Energy Crunch. Let's start with the high-tech, super-costly solutions that many promote as the surefire source of abundant, affordable energy: thorium reactors, mini/modular-reactors, clean coal plants and fusion.

Every one of these may turn out to be a solution, but in the here and now they take many years to build and huge sums of money. Full-scale functioning examples of these technologies do not yet exist. Various prototypes are in development, but the timelines are long and uncertain.

For example, one modular nuclear reactor design recently gained approval, and the first prototype will hopefully be ready for testing in 2030. As for when we can expect the first full-scale modular nuclear reactor to start producing electricity, nobody knows. How many units can be manufactured per year is also unknown. Any practical guess is decades.

Nuclear reactors are costly to build, regardless of their fuel cycle. Cost and time over-runs are the norm. Five years becomes nine years and $1 billion becomes $3 billion. New technologies are especially prone to over-runs. There are about 440 functioning nuclear reactors on the planet and about 55 under construction in 19 countries. The existing reactors supply about 10% of global electricity--in other words, a fraction of total energy consumption.

As for everyone's favorite solution, the so-called renewables of wind/solar--actually replaceables--we all know the problem: they're intermittent. So you need a second power generation system to fill the gaps when the sun goes down and the wind dies. As for batteries-- even mega-batteries only hold a tiny percentage of total energy consumption. And it's already clear that there aren't enough minerals to build hundreds of millions of high-tech batteries, which by the way, are also replaceable, i.e. must be replaced every decade or so. (See chart below.)

Common-sense suggests it is folly to shut down existing energy sources until a replacement system is up and running. Yet that seems to be official policy in many places. The idea that getting rid of undesirable energy sources will magically create desirable energy sources is delusional, yet that idea is apparently quite compelling.

Maintaining two energy generation systems--one intermittent and one for backup--is inherently more expensive than having one system. Whether the backup is battery or another energy source (or some of both), it doesn't matter: the cost is greater regardless of the type of backup.

The global energy crunch is real and has no easy, cheap, quick fix. That doesn't mean we're powerless (heh).

Let's ask a few questions of the planet's largest energy consumers: Europe, North America, China and Japan.

1. What percentage of habitable structures are well-insulated or super-insulated to minimize the need for heating / cooling?

2. What percentage of habitable structures have geothermal heat pumps (GHPs) that use the ambient temperature of the Earth to reduce energy consumption?

3. How many empty rooms / spaces in these regions are heated / cooled?

4. How many of the millions of vehicles that are stuck in traffic jams are single-occupant?

You see where this is leading: conservation is the fastest, lowest-cost, lowest-technology way to reduce energy consumption by reducing waste. Rather than invest in universal conservation and incentives to reduce wasteful behaviors (heating empty spaces 24/7, etc.), we've squandered decades and trillions of dollars, yuan, yen and euros on bridges to nowhere, wars of choice, speculative excess, virtue-signaling and the mindless consumption of the waste is growth Landfill Economy.

We've squandered trillions that were borrowed and now we have to pay interest on the wasted money.

Many solutions are solely behavioral and require no new infrastructure at all. For example, everyone driving themselves to the city center could stop at a bus stop or equivalent gathering place and pick up three other commuters. Tollways could be reprogrammed to reward vehicles with four passengers.

There are many such behavioral solutions that conserve energy on a mass scale. For some mysterious reason, we seem collectively enamored of high-tech solutions that demand decades and trillions of dollars rather than solutions that are within reach.

Waste is not growth. This is the central delusion of the modern economic mindset and the global economy. Eliminating glaringly obvious waste and using basic technologies (geothermal heat exchange, insulation) are the common-sense first steps to the goal of maintaining energy supplies at affordable levels.

The technologies to radically reduce waste have been around since the late 1970s / early 1980s. Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) (Wikipedia):

By 1978, experimental physicist Amory Lovins had published many books, consulted widely, and was active in energy affairs in some fifteen countries as synthesist and lobbyist. Lovins is a main proponent of the soft energy path.

At RMI's headquarters the south-facing building complex is so energy-efficient that, even with local -40 °F (-40 °C) winter temperatures, the building interiors can maintain a comfortable temperature solely from the sunlight admitted plus the body heat of the people who work there. The environment can actually nurture semi-tropical and tropical indoor plants.

Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI)

If we insist on doing the transition the hard, slow, costly way rather than the easy, fast, cheap way, it's going to be a needlessly arduous, soul-crushing slog. Perhaps we need some uncommon sense since common sense appears to be so scarce.

Comments

Post a Comment