The Journey to Zero Risk

The Journey to Zero Risk

is paradoxically risky

Edward Abbey’s burial was a reflection of his life: He asked friends to wrap him in a sleeping bag and bury him in the desert, as illegally as possible, to the sound of gunfire and bagpipes. All of which they more or less did, apparently minus the bagpipes, stopping at a liquor store (with his body in the back of their truck) to buy some whiskey to pour on the grave.

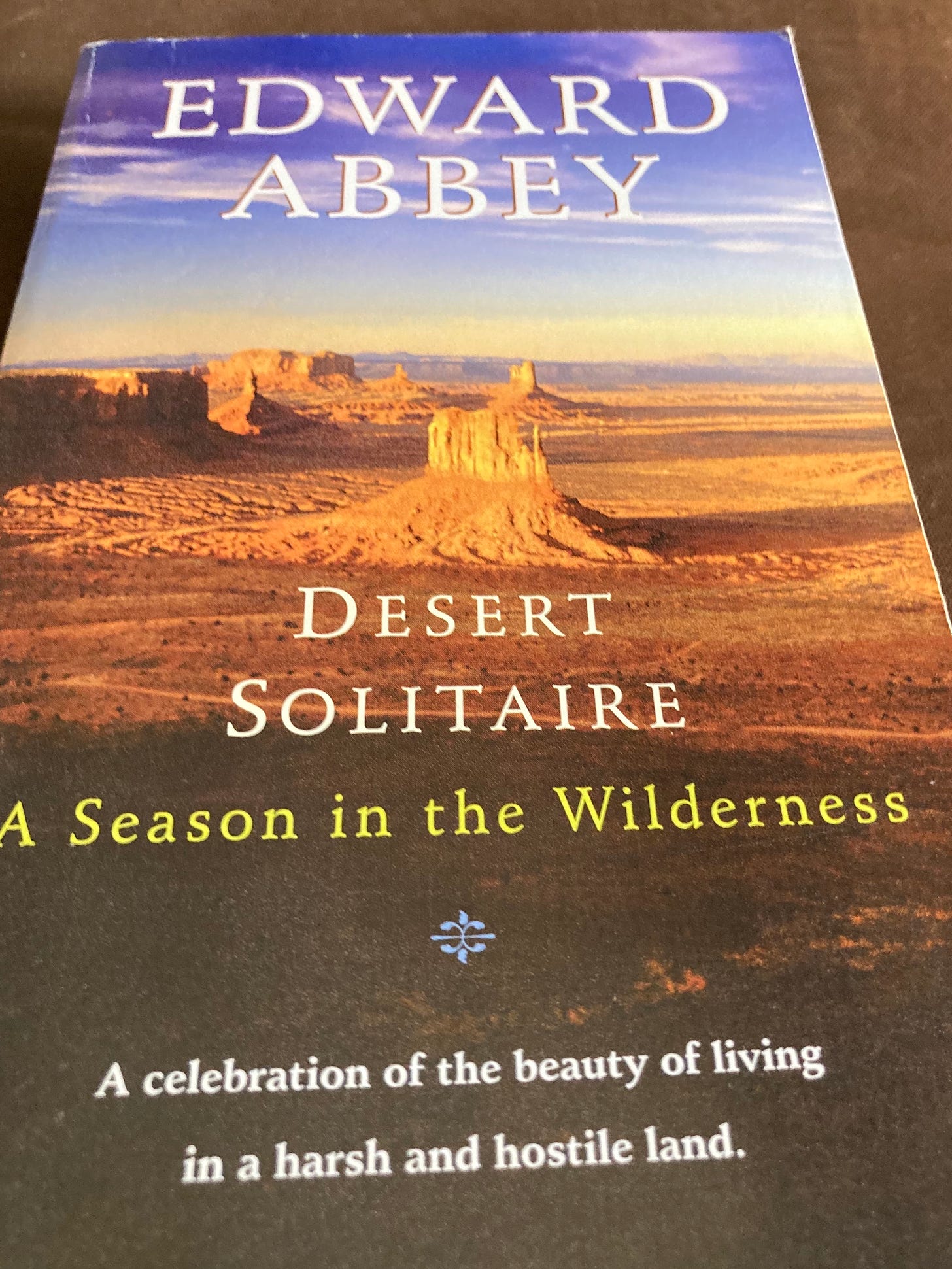

Abbey was another one of those great men who weren’t invariably good men, and his laundry list of wives often didn’t enjoy being married to him. But he lived in pursuit of beauty and with indifference to discomfort and the possibility of death, in ways that show up in most of the stories he told. His life becomes a serial account of a decades-long journey through the arid Southwest, usually undertaken without enough water. Here’s a paragraph from Desert Solitaire about a trip through Glen Canyon with a friend:

Afterwards as we pack and load the boats, sun coming up over the rim, we begin to feel the familiar terrible desert thirst. We drink the last of the spring water in our canteens and, still thirsty, look to the river, that somber flow the color of burnt sienna, raw umber, muy colorado, too thin to plow — as the Mormons say — and too thick to drink. But we drink it; we’ll drink plenty of it before this voyage is over.

Your REI shopping guide reminds you to take proper filtration devices, campers, and always have a back-up plan to treat water from natural sources. But Abbey frequently didn’t even bother with the canteen, setting out on desert hikes with the expectation of finding…something to drink. Somewhere.

In another passage he finds a desert waterhole with no signs of animal life, a warning (along with the smell) that the water is poison. So he tastes a little, and spits it out, just to see what poisoned water tastes like. The tagline on the cover of this book casually describes an entire worldview in a single sentence:

Beauty in harshness and hostility, living joyfully with deprivation. A celebration of harshness.

Abbey makes me think of Dick Proenneke, who loved the deep Alaskan wilderness so much he moved there. Alone. With some hand tools to get a cabin built before winter. A friend with a float plane occasionally flew in some bacon and his mail.

Compare this attitude about life and risk to the column I wrote about yesterday, the op-ed piece in the San Francisco Chronicle by an editor who caught the dreaded Current Thing after hiding indoors to avoid it. There’s a funny part here, and you don’t have to work that hard to find it:

For more than two years I basically lived like a hermit to avoid just this scenario. Sure, after getting vaxxed and boosted I didn’t think COVID would kill me. But I don’t exactly have a gold medal immune system; even a common cold gives me a rough time. I imagined COVID would lay me out with symptoms that could drag on for weeks or possibly months. So I stayed away from the office, indoor gatherings and restaurants. The gym? No thanks. Fifteen extra pounds was worth it to avoid getting sick.

Weirdly, the person who hides from illness by living like a hermit for years finds that his immune system is poor. He avoids all risk, which elevates his risk.

Now, watch 59 seconds of life spent in a defensive crouch:

I’ve written before about dependency as a political and economic maneuver, and a way of life that takes from you while hidden behind the appearance of helping.

The debilitation of the zero-risk life is obvious to everyone but the debilitated.

Comments

Post a Comment