Futures That Work

Futures That Work

Among the most curious features of the current predicament of industrial society is that so much of it was set out in great detail so many decades ago. Just at the moment I’m not thinking of the extensive literature on resource depletion that started appearing in the 1950s, which set out in painstaking detail the mess we’re in right now. I’m thinking of those writers who explored the decline and fall of past civilizations, in the vain hope that ours might manage to avoid making all the usual mistakes. In particular, I’m thinking of Arnold Toynbee.

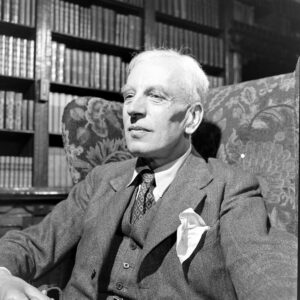

Arnold Toynbee, contemplating the idiocy of failing elites.

Toynbee’s all but forgotten these days, but three quarters of a century ago his was a name to conjure with. His gargantuan 12-volume work A Study of History set out to trace the histories of all known civilizations and, from that data set, determine the factors that drove the rise and fall of human societies. One- and two-volume abridgements leaving out most of the supporting data were widely available back in the day—my parents, who were not exactly highbrow East Coast intellectuals, had a copy on a bookshelf in the family room when my age was still in single digits. Plenty of academic historians denounced Toynbee, but a great many people read his work and saw the value in it.

Those days are of course long past, but there’s an interesting twist to the disappearance of his ideas from the collective dialogue of our time. Those ideas weren’t rejected because they turned out to be wrong. They were rejected because Toynbee was right.

To summarize an immense body of erudite historical analysis far too briefly, Toynbee argued that new human societies emerge when a human society is faced with a challenge it can’t meet using its previous habits of thought and action. Many societies faced with such a challenge simply go under, but now and then it happens that a creative minority is able to come up with alternative ways of thinking and acting that meet the challenge successfully. The creative minority then becomes the guiding class of the society; even if it doesn’t hold political and economic power itself, its ideas and insights seize hold of the imaginations of the ruling class and direct the energies of the entire society.

A successful creative minority isn’t satisfied with a single set of good ideas. That’s essential, since the world isn’t so unimaginative as to keep challenging a society over and over again in the same way. Sometimes a challenge demands new ideas and new strategies; sometimes it requires doubling back and using something that worked a long time ago; sometimes a single mental leap is all that’s needed, while sometimes a prolonged period of muddling through is on the agenda. The creative minority has to stay nimble and pay close attention to what’s actually happening in order to keep solving problems and retain the loyalty of the rest of society.

That’s how civilizations rise. Civilizations fall, according to Toynbee, when the formerly creative minority stops being creative and sinks into a rut. In Toynbee’s terms, it changes from a creative minority to a dominant minority, and it settles for maintaining control over the society by force and fraud because it no longer has the ability to inspire confidence and loyalty by coming up with effective responses to the challenges faced by society. You know that your society is run by a dominant minority when, no matter what the problem is, the people in power always insist on the same solutions. You also know that your society is run by a dominant minority when the same problems come up over and over again, because they’re never actually solved—they’re just swept under the rug in a frantic effort to insist that the same old solutions really will work.

I was reminded of all this forcefully the other day by the news from Britain. One of the more interesting features of the British political system, at least from an American perspective, is that the lack of checks and balances in Britain’s unwritten constitution means that its parties can be far more blatant about their agendas in public than ours usually manage. Liz Truss, for example, didn’t have to convince a majority of the voting population of Britain to put her into No 10 Downing Street; she just had to make nice with the members of the Conservative Party, and so could be much more forthright about her intentions. The same point is just as true for Keir Starmer, the current head of the Labour Party: all he needs is a majority of party members to keep backing his program, no matter what the rest of the population thinks of it.

Thus I trust it came as no surprise to anyone that once Truss became prime minister, one of her first priorities was to cut taxes on the well-to-do. Making life easier for the rich has been a central goal of the Conservative Party since there was a Conservative Party, and now that the populist wing of the party and its scruffy standard-bearer Boris Johnson have been driven out of power, the old guard represented by Truss promptly tried to get back to doing what they and their predecessors have been doing since powdered wigs were all the rage. Most other people in Britain know perfectly well that cutting taxes on the rich won’t do anything at all to help Britain’s crumbling economy or its increasingly desperate energy shortage, as the public reaction demonstrated, but here we’re in the territory Toynbee mapped so precisely: Truss and her government tried to insist that the nation’s problems have to conform to their preferred solutions, rather than adapting their proposed solutions to the nation’s problems.

Keir Starmer. He hasn’t had a new idea yet.

And Labour? They’re doing exactly the same thing with a different set of failed solutions. At a Labour Party conference last month, Starmer unveiled a grand plan for Britain’s energy future. You guessed it: more wind turbines, more solar photovoltaic farms, gargantuan investments in hydrogen as an energy storage and transport medium, all with the goal of getting Britain to use next to no fossil fuels within a decade or so. All this was propped up as usual with the standard rhetoric about global warming, as well as a great deal of talk about the impact of energy costs on the ordinary people of Britain. Now of course global warming is a real issue, and so is the burden of soaring energy costs, but it bears remembering that it’s quite possible to grasp that there’s a real problem but go on to commit to a solution that won’t work.

We already know, after all, that Starmer’s project won’t work. Germany pursued the same set of gimmicks most of two decades before, and it failed. As I noted on this blog two weeks ago, if windpower and solar PV farms could provide an industrial nation with an adequate energy supply, the Germans would be fat and happy right now, powering their industrial system on wind and sun while the rest of the world reeled under the blows of high energy costs. In case you haven’t noticed, that’s not what happened. Wind and sunlight are diffuse, intermittent energy sources very poorly suited to a modern power grid, so the illusion of the German Energiewende was propped up with vast amounts of cheap Russian natural gas. Now that the prop isn’t there any more, industrial firms are leaving Germany as fast as they can, while ordinary Germans are bracing themselves for a winter of blackouts and energy rationing.

You’d think that any sane person observing this would recognize that copying the Energiewende and going whole hog on windpower and solar PV is a very bad idea. You’d be right, too, but that’s where Toynbee’s analysis shows its strength. Keir Starmer and the other members of the Labour Party leadership have embraced wind turbines and PV panels as The Right Things To Do, and the mere fact that those don’t accomplish what they’re supposed to accomplish never finds its way through the haze of abstractions that dominates political discourse today.

That’s not just a British problem, to be sure. The state government of California has committed itself to the same ruinously ineffective program for exactly the same reasons. California is accordingly on track to become the Rust Belt of 21st century America, with industries, jobs, and residents fleeing at a record pace, while Governor Gavin Newsom blusters and preens himself on his state’s ongoing barrage of virtue signaling. Here again, a fog of abstractions that define windpower and PV as The Right Things To Do makes it impossible for Newsom to recognize that the policies on which he’s betting his political future and the economic survival of his state have failed whenever they’ve been tried and won’t work any better this time around.

Nor, of course, is it any smarter to double down on that other failed technology, nuclear power. When I talked about the fantasies and failures of nuclear power two weeks ago, I fielded the inevitable lectures from nuclear power groupies about how the only problem with nuclear power is that people are irrationally afraid of it, it really is the solution to all our energy problems, and so on endlessly along lines laid down when Eisenhower was in the White House. It somehow never sinks in that even in those countries that have autocratic governments and next to no environmental regulation—China comes to mind—nuclear power has proven to be a technical success but an economic flop. In the eyes of nuclear fanboys—you won’t find many fangirls in that scene—nuclear power is The Right Thing To Do, and mere facts can’t get a word in edgewise past that devout conviction.

If you want a litmus test for the mode of elite failure that Toynbee anatomized, in fact, all you have to do is point out the history of repeated failure to some true believer in windpower and solar PV, or for that matter the comparable history of repeated failure to a true believer from the leftward end of the glow-in-the-dark lobby. If you can get past the flat insistence that it just ain’t so, and the various attempts to weasel the numbers around to avoid the lessons of repeated failure, you can pretty reliably count on getting a lecture about how awful climate change is going to be, winding up with an insistence that windpower and solar PV, or nuclear power, or all three, are the only alternatives to planetary doom. Notice the weird logic: if the situation is really that bad, does it make any sense to cling to a supposed solution that won’t fix it? In the minds of Starmer and Newsom, or their equivalents in nuke fandom, apparently so.

Another poster child for repeated failure.

It also deserves to be said here that the threat from global warming, serious as it is, is being wildly overinflated in the mass media and the climate-activist scene. Consider the recent hullaballoo about the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica. The Thwaites Glacier is huge—roughly the size of the state of Florida—and it contains enough ice that, if it were all to melt, sea levels worldwide would go up around 26 inches: enough to cause serious problems in low-lying coastal areas around the world. In recent years, furthermore, the floating ice shelf where the Thwaites Glacier empties into the ocean has begun to break up; current estimates are that it will certainly be gone in a decade, and may collapse in as little as 3 to 5 years.

Once the ice shelf goes, the rest of the Thwaites Glacier will begin to slide more rapidly into the sea and melt, a process that will take fifty to a hundred years to complete. The Thwaites Glacier, in turn, makes up a large part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which contains enough ice to raise sea levels worldwide by ten feet; the collapse of the Thwaites Glacier’s ice shelf is thought to be a harbinger that other parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are moving toward a similar fate over the next few centuries. All in all, it’s not exactly welcome news for us or our descendants.

That sort of reasonable concern isn’t what’s finding its way into the news, though. The corporate news media are insisting instead that the collapse of the Thwaite Glacier’s ice shelf means that sea level will certainly rise ten feet. Climate activists, eager to outdo the mass media in the exaggeration Olympics, are now insisting that this ten-foot rise will surely happen within three to five years unless all the world’s nations stop using fossil fuels and throw all available resources into figuring out how to stabilize the ice shelf.

I suspect most of my readers recall that according to Al Gore, New York City was supposed to be underwater by now. The main reason why most people in the industrial world roll their eyes and start talking about something else when climate change gets brought up is precisely this habit of taking a serious issue, puffing it up into apocalyptic absurdity, and then pretending that nobody said anything of the kind once doomsday passes and the predicted cataclysm yet again fails to arrive. This is another example of the fixation on failed solutions we’ve been discussing. What shall we do to motivate people to take climate change seriously? Let’s panic them by trotting out shrill apocalyptic claims! And if people stop believing the claims when they turn out to be false? It’s that last question that never gets asked in climate change circles, because the habit of making overwrought predictions of doom has been assigned the role of The Right Thing To Do.

Of course there are alternatives to the fixation on failed strategies that Toynbee anatomized in such detail and we’ve surveyed here. The most important of them is an option we’ve already discussed: nstead of trying to force the problem to fit a prearranged solution, find solutions that have some hope of dealing constructively with the problem.

The current situation in Britain is a convenient example. To deal with a serious energy crunch and the soaring prices resulting from it, the Conservatives want to cut taxes so the rich get richer and everyone else has more money to hand over to the energy companies, while Labour wants to sink billions of pounds into a set of green energy technologies that won’t work. Are there other options? Of course there are. To begin with, most buildings in Britain are poorly insulated and lack other basic conservation measures: the lessons of the 1970s energy crises have been forgotten just as thoroughly on that side of the pond as they have been over here.

A systematic program of weatherization for British homes, shops, and factories could quite readily shave 10% off the nation’s energy costs and might well, if it were intelligently designed and applied, get significantly above that figure. Since energy prices are set at the margins, this would have an outsized effect on energy prices. With energy as with money, it’s almost always easier to reduce outgo than it is to increase income, and a vast amount of energy used today in industrial nations is wasted pointlessly without making any contribution to quality of life. Cutting down on that waste is an easy fix that would help a lot of British people very quickly.

Britain also has a huge, functional, but almost entirely neglected energy-efficient transport system in its canal network. Relatively modest investments in canal improvements would enable a significant share of domestic freight to be transferred to canal boats and shipped for a tiny fraction of the energy cost needed for other modes. Reactivating the canal network would also provide a resilient, sustainable worst-case transport network that would remain viable even during severe energy shortages. This is something that British officials and ordinary Britons should have in mind for the future, since the world’s remaining concentrated energy reserves are depleting steadily with each day that passes.

Are these two the only options? Of course not. Are they the best options? That’s a question best settled by local and regional-scale experiment, backed up by detailed analysis by people who don’t have an ideological commitment to either side of the question. Which options will work best will vary considerably from one part of Britain to another, which is why projects to conserve energy and find less extravagant ways to meet human needs and wants would be best managed by individuals, families, local communities, and regional organizations rather than by central planning from London.

Set aside the things that have already been proven not to work, look at unfashionable possibilities that do work, consider all the options, and make ample room for personal, local, and regional experimentation: that approach offers genuine hope at a time when the establishment is busy pursuing policies that have already proven hopelessly inadequate. Put enough effort into this less rigid approach, and it becomes possible to piece together a toolkit of possibilities that would make the twilight of the fossil fuel age much less difficult for everyone. That’s a goal worth pursuing. Even though it’s very late in the day and vast amounts of time and resources have already been wasted trying to force the world to conform to a set of prearranged narratives, it would still be possible to accomplish quite a bit.

California could do its own version of the same thing. So could the United States as a whole—we waste even more energy per capita than the British do, though there are other countries that beat us hands down in the waste sweepstakes—and we would benefit hugely from such a project. So would Germany, for that matter, or any other industrial nation. Will they? That’s the big question, of course. If the current leadership of each of these societies remains stuck in their current status as dominant minorities, clinging to power even though they haven’t had an original idea in decades and have no notion how to deal with the spiraling crises of the present, then there’s little if any chance that anything of the sort will happen.

On the other hand, it’s just possible that the people in power might remember that their job is to find solutions to fit the problems we face, not try to bully problems into fitting their preferred set of solutions. It’s also possible that enough people could come to terms with the failure of familiar narratives to put a new set of people into power who have grasped this crucial point. If that happens, rough though the transition may be, we can let go of the shopworn twentieth-century futures that have failed so reliably, and get busy building futures that work instead.

Comments

Post a Comment