The Sorrows of War

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Sorrows of War

[Vung Tau, Vietnam on 8/27/22]

On 7/27/23, there’s a wrenching tale in the Vietnamese newspaper, Tiền Phong [Vanguard]. The author was Thu Hiền. Certainly a pen name, it means benign or gentle autumn. Of course, that season of falling leaves connotes death. Though dreaded, it’s only a curse if comes too early. Nothing is worse than eternal decrepitude.

Death, then, is a thousand autumns. Lying still, one reflects on all that has been wasted, thwarted or snuffed out, and not just by fate, but one’s confusion or cowardice. Shifting maggots rearrange one’s bones. If only one could sigh.

Thu Hiền tells us about a 2022 wedding between Nguyễn Thị Diện, born in 1947, and Đặng Văn Cự, a year older. It’s odd enough when septuagenerians tie knots, and not as divorcees or widows, but for the first time. They had long been each other’s first love. Odder still, they had been dead for 51 years, since 1972.

During war, a vast army of civilians must serve near the front line, so many die.

Now 73-years-old, Diện’s brother recounts news of her death, “One evening near the end of 1972, my unit’s commander said I was allowed to go home for an unspecified family matter. With premonition, I walked all night, over 12 miles, to reach our house. There, I saw my mother sobbing, with my sister’s death notice next to her. It said she had died under fire on the Yellow Boat River, in Tuyên Hóa District, Quảng Bình Province, on 12/29/72.”

Still grieving, the brother remarks that, as a teenager, his sister was an outstanding swimmer, and even finished second in the entire province for her skills at shooting a rifle while lying, kneeling or standing, and for her excellence at hurling hand grenades.

Three years later, the war ended. Still, the brother had to wait 19 more years before looking for her grave. He hadn’t the money to travel just 125 miles. With so many war cemeteries in Quảng Bình, he could only find his sister after three trips.

“Kneeling in front of her grave, I couldn’t speak, only sob. Next to her grave was that of Đặng Văn Cự.” In a single letter home, she had mentioned him as someone she intended to marry.

Several times, the brother tried to bring her home, but couldn’t. Her spirit said no.

“Perhaps she had become attached to that place since her youth, and she had lain there among her comrades for half a century. Plus, she was at rest next to her beloved, so couldn’t bring herself to go far away. Thinking this, our family decided to leave my sister at peace, next to brother Cự and her comrades.”

As for Đặng Văn Cự, it wasn’t until 2022 that his family managed to locate his grave. Soon after, they met their future in-laws, so a wedding was arranged. Traveling from Bắc Giang to Nghệ An, the groom’s family brought rice, chickens, areca nuts and that mung bean filled cake that had been around since at least the 12th century. Meant for wedding proposals, bánh phu thê literally means husband and wife cake.

After a banquet at the bride’s home, both families traveled to the graves of the newly wed. Lighting incense sticks, they prayed. Forever young in black and white, the bride smiled demurely. Out of nowhere, a white butterfly alighted on a bouquet next to her face. In its blue and white ceramic jar, a bundle of incense sticks miraculously flared up.

In the genealogy that’s kept inside each family’s temple, an adjustment had to be made. Đặng Văn Cự could no longer be listed as “passed away in youth, without a wife and children.” Nguyễn Thị Diễn had become his wife.

This article’s title, I lift from Bao Ninh’s novel, of course. Though the author fought on the winning side, his depiction of war is infused with sadness and, yes, even a sense of defeat, for war is mostly about losses, of lives, limbs, sanity, innocence and possibilities. Spreader of abject fear and squalid death, war disfigures everything.

Since war can’t be exorcised from human affairs, we must brave its horrors. At the beginning of Bao Ninh’s novel, the protagonist, Kien, is tasked with retrieving soldiers’ remains. Exhausted on the back of a truck, he sleeps on a hammock above what’s left of his dead comrades, “laid out in rows.” Above him, rain pours through the holes of a torn tarpaulin. Already, we have a symbolic picture of man, haunted, hounded and not quite sheltered. A reluctant warrior, he must fend off his species’ worst tendencies.

Worried over his aging mother struggling alone back home, a soldier, Can, tells Kien he’s about to desert. Since it’s a trek of 800 miles through hostile territory, with all sides, plus nature, seeking to kill him, it’s a definite suicide. Plus, it’s shameful, Kien tells him.

“In all my time as a soldier I’ve yet to see anything honorable,” Can replies.

Bao Ninh’s novel’s original title was The Fate of Love [Thân phận tình yêu]. Very cheesy, certainly, and revealing of the author’s artlessness, if not innocence. In an unpublished interview with Amanda Zinnoman, Bao Ninh says most North Vietnamese of his generation knew next to nothing, for they had few chances to study or even read. In each company, there was a soldier carrying books in a backpack, but these were mostly ignored. Coveted books were found only in destroyed South Vietnamese homes.

To all the losses and sorrows of war, one must add the distortion, perversion or even erasure of culture. With its ethos of constant war, one country exceeds the rest in this plunge to the bottom. The brightest fireworks in the darkest depth await them. Insatiable for destruction, they’ve been hankering for it.

In 1995, I rode on the back of a motorbike to Bao Ninh’s house in Hanoi. Though I was working on an anthology of contemporary Vietnamese fiction, I had published nothing. Still, Bao Ninh didn’t hesitate to pour me glasses of Johnny Walker Black Label. Genuinely warm, this solid man had no pretensions.

Having survived the Jungle of Screaming Souls, Bao Ninh was glad to be restored to a relatively cultured environment. Most of his comrades never had a chance.

[memorial to Hezbollah fighters in Al-Quala’a, Lebanon on 11/4/20]

[Philadelphia, 11/12/13]

[Anton Ryzhenko on piano at Bar Baraban in Kiev, Ukraine on 2/18/16]

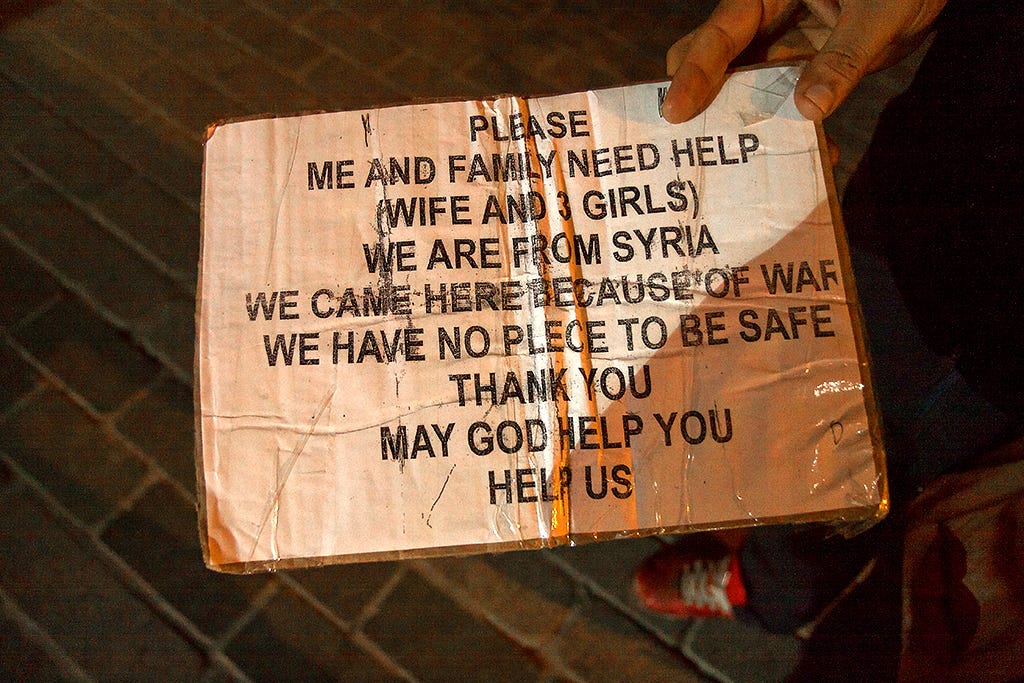

[Istanbul, Turkey on 12/25/15]

Source : Postcards from the End

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment