The Mysteriousness of Conspiracy

The Mysteriousness of Conspiracy

And the need to pretend otherwise

i. Conspiracies are political

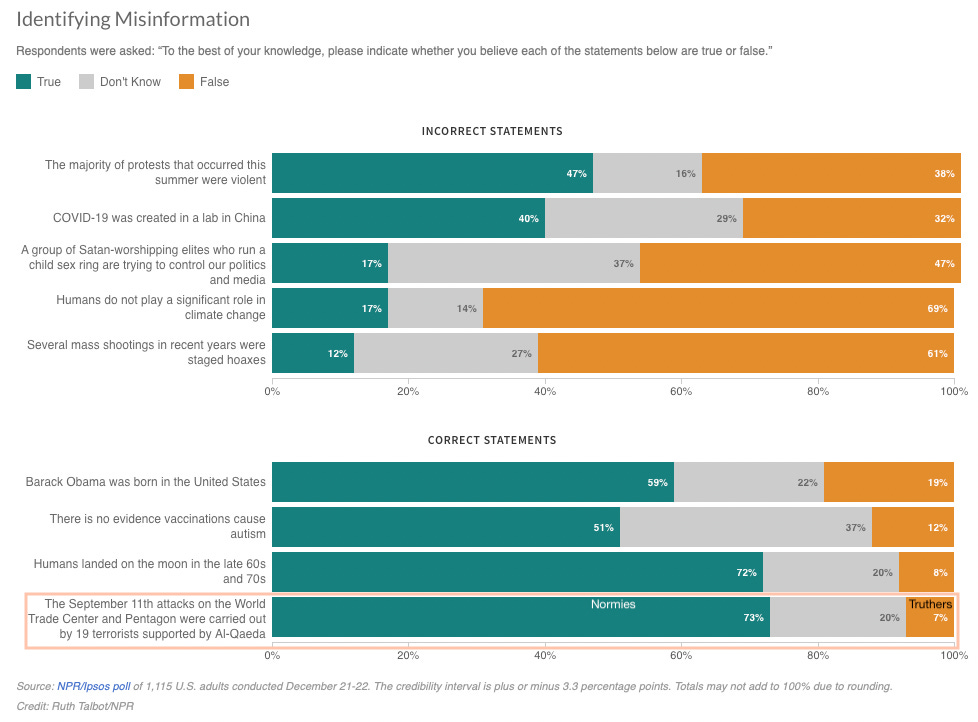

On the eve of the 20th anniversary of September 11, an NPR/Ipsos poll found skepticism of the official narrative to be the least popular of numerous flagship conspiracy theories of the time:

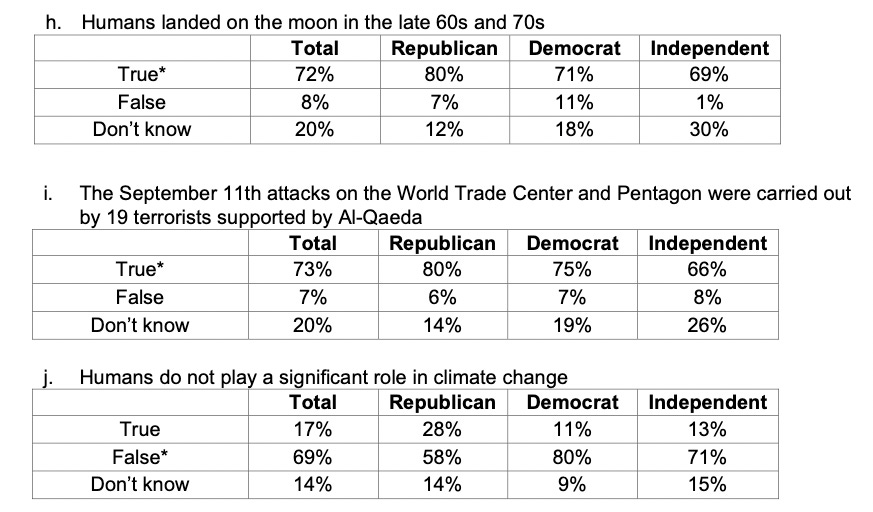

This result is driven by ambivalence among Republican-identifying respondents, who drive the high rate of “false beliefs” in more contemporary topics. A comparison with replies for the moon landings and climate change show that Democrat respondents are just as likely or more to have doubts about the two older topics.

This is one of many ways by which belief in conspiracy theories reveals itself to be less a question of what is believed than a symptom of broader tensions and conflicts between the individual and society. Conspiracy theories, it requires no original thought for me to say, are ways to make sense of the world, and of doing so in a way that posits society to be led astray from cryptic truths by evil agents. One sees that something is wrong with society (often, that something is changing within it, degrading old values), and concludes that society is being tricked into believing falsehoods. Obama threatens American white cultural hegemony; society has been tricked into believing he is American.

ii. Conspiracies are allegorical

This doesn’t mean that in making sense of the world by positing society to be led astray from cryptic truths by evil agents, conspiracy theories get it wrong.

The reigning scientific consensus on climate change — that human emissions of CO2 are responsible for increases in observed temperatures and that no yet-unknown natural feedbacks will prove to temper or reverse these observations, producing historical example four trillion and one of human ignorance of reality — is something between reasonable (but wild) speculation and faith. In many ways, there is nothing wrong about describing the consensus to claim knowledge about the climate where it does not exist (and to report it in the media) as a conspiracy.

And so here, the “evil agents” are the scientists claiming consensus and the media, and the truth being hidden from society is that no one really knows what CO2 is going to do to the weather and the sea levels long term, because after all, there is no lab on Earth to tell us what (specifically) Earth as a whole will do in response to +1X. Even if the scientists and media are to a great extent blind to the limits of their knowledge — if they confuse their faith for understanding, and as they are deceiving themselves are not in a true sense conspiring to deceive everyone else — the conspiracy theory has made sense of reality in a rather accurate fashion.

At the same time, the incompletely partisan nature of the rejection of the claim reveals that this is less a question of rejecting faith because it is faith rather than because there is disagreement among two competing faiths. On the Republican side, we can imagine that trust in institutions competes with trust in economic prosperity to produce a divided stance on the modern faith in climate change. Few, likely, are rejecting the theory on epistemic grounds. The point is that both believing in the conspiracy theory and not are a way of making sense of the world; they are participatory interactions with a social consensus.

iii. Conspiracies are possible

Consider, as well, how believing that conspiracies are impossible is not much different than believing in the climate change narrative. By “Believing That Conspiracies Are Impossible,” I refer to the claim frequently made by those who wish to dismiss some particular conspiracy theory that no attempted conspiracy can be pulled off successfully. Typically, an example is offered of a very small conspiracy that failed due to betrayal, e.g. Watergate.

This itself is a faith, of course, and it has counter-examples. We may consider Enron, which was a long-running conspiracy of fraud that was only found out because an outsider discovered the evidence of the fraud in the larger system surrounding the conspiracy. Since the scandal is common knowledge, I will lazily quote from a somewhat under-cited wikipedia summary (emphasis added; citations available in original, but note that they are incomplete):

In 1990, Enron's Chief Operating Officer Jeffrey Skilling hired Andrew Fastow, who was well acquainted with the burgeoning deregulated energy market that Skilling wanted to exploit. In 1993, Fastow began establishing numerous limited liability special-purpose entities, a common business practice in the energy industry. However, it also allowed Enron to transfer some of its liabilities off its books, allowing it to maintain a robust and generally increasing stock price and thus keep its critical investment grade credit ratings. […]

The first analyst to question the company's success story was Daniel Scotto, an energy market expert at BNP Paribas, who issued a note in August 2001 entitled Enron: All stressed up and no place to go which encouraged investors to sell Enron stocks, although he only changed his recommendation on the stock from "buy" to "neutral".

As was later discovered, many of Enron's recorded assets and profits were inflated, wholly fraudulent, or nonexistent.

Enron had (per the same wikipedia page) 20,600 employees in 2000, year eleven of Skilling and Fastow’s conspiracy. If even a fraction of their workforce observed the irregularities throughout those years, then we have a conspiracy sustained by 100s or 1,000s of individuals — no one talked. This fails to count other individuals outside of Enron, especially in companies working with them, who likely noticed problems before Scotto.

Likewise, if the mainstream, social-consensus understanding of Enron openly implies a conspiracy, it implies that the mainstream understanding itself could be the fraud. Perhaps Enron was imploded based on totally fabricated figures to cheaply transfer the company’s fiber optic and data footprint in a secret auction (as occurred1). Chinatown in Las Vegas (and Chinatown was inspired by a historically disputed conspiracy theory involving the San Fernando land syndicate). Would this require more or fewer silent conspirators than the mainstream narrative?

Conspiracies are obviously possible. Therefore there are probably many that have never been discovered; and potentially at least one conspiracy theory somewhere, at any time, which is yet to be acknowledged as true.

iv. Conspiracies are not impossible

More broadly, to return to my point, a belief that conspiracies are impossible expresses and acts upon a wish to understand social consensus as having a reliable overlap with reality. It is a wish to not see that oftentimes, the things that everyone held to be true, that the experts all said were true, suddenly cease to be held to be true. Enron was a success story one day; it was a scandal the next. “SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab in China” was a “false statement” in 2020, today it is a “true statement” in much of the media.2

Again, the epistemic reality — the fact, observable to the plain eye, that no one really knows anything beyond their own sphere of expertise, and often not even within that — is being sidestepped, and matters of faith are being used according to one’s perception that something is or is not wrong with society. Those Who Believe Conspiracies Are Impossible are merely expressing investment in the trust of experts who now get to author our society’s consensus beliefs, including about the nature of complex systems. They are warriors of faith: “What the consensus holds today, it has always held (since the experts were put in charge), and will always hold (as long as we do not doubt the experts).” This is only necessary to believe because it sustains a notion that giving the keys to the social consensus over to experts has improved the reliability of vehicle operation. Meanwhile the paradox — “it is impossible that the experts are wrong, because if they were wrong, someone would say, and therefore we must never question the experts, and shame to all who would” — is obvious.

v. Conspiracies are unnecessary

If having experts in charge of the social consensus does not eliminate the hazard of consensus reversals, no conclusion is demanded beyond the fact that clearly the experts can get things wrong. That they are fallible does not demonstrate that they are nefarious; and conversely that they are nefarious would require that they are infallible. A more parsimonious conclusion is that nothing about expertise confers infallibility — after all, experts disagree. Different countries have different experts who, within their own circles of dialogue and political backdrops, will have conflicting beliefs with other countries’ experts. Unless the laws of reality adhere to national borders, therefore, the differing consensuses of different geographical nexuses of experts cannot all be correct. Experts are fallible.

Thus, even if faith in climate change is allegorically well-explained by conspiracy theories, there is not necessarily any “conspiracy” at work. The scientists, media figures, NGOs, and politicians invested in the cult of climate change are not “evil” in the sense of willing to deceive; they all sincerely mistaken. The “evil” is the false belief itself, which has, like the temptations of sin, led them astray.

This grants a substantial point back to Those Who Believe Conspiracies Are Impossible. Given that conspiracies (in practice, at times) require a solidarity of silence, it seems more likely that in most of the cases when the expert-backed social consensus is wrong, it is simply due to the honest fallibility of experts. Those Who Believe Conspiracies Are Impossible can in this way obscure or overcome their faith by acknowledging that experts often “emerge” into false consensus beliefs due to human failings, and thus apparent conspiracies — like the Covid lockdowns — are (as I myself have argued3) mere comedies of error.

This doesn’t satisfactorily explain what is often a dogmatic unwillingness to dialogue with conspiracy theories in general on the part of such enlightened TWBCAI-ers; but it remains that it is not difficult to make the case that to indulge in conspiracy theory thinking in general is to work a mine known to yield fool’s gold. The social consensus is not tied reliably to the truth, and no fraternities of evil men are required to lead it astray.

vi. Conspiracies are ignorable — and sometimes, must be ignored

Now we return to the question of 9/11, the most obviously true conspiracy theory perhaps in history, certainly in living memory. There is a “cryptic” truth — the mainstream narrative does not account for the evidence, and thus, some different set of events must have generated this same evidence — and a fair chance that the suppression of this truth was orchestrated in some manner (as opposed to naturally “emerging” in the consensus of the 9/11 Commission). Not only that, but the contrast between the mainstream narrative and the evidence is in no way obscure — everyone knows that the narrative claims the jets and their dozens of passengers were in four of four cases overcome using box-cutters; everyone saw the buildings self-destruct on video.

But if so obvious, why did 9/11 “trutherism” remain the least popular conspiracy theory in the 2020 NPR/Ipsos poll? It cannot be for example that the four in five Republican respondents who demurred the opportunity to deny that a network of Satanist pedophiles run the government are afraid of defying social taboos on wrong-speak. What makes those same four in five affirm the narrative on 9/11?

Here it is appropriate for me to link to today’s requiem for trutherism by Ron Unz, at Unz Review. Unz describes how the movement to expand awareness of the physical evidence contradicting the mainstream narrative lost steam after the mid-2010s, after which the podium was increasingly occupied by outlandish and unrigorous claims possibly planted to discredit the movement. Trutherism as a serious enterprise is all but dead; it shuffles off to the same historical grave-yard plot that holds Pearl Harbor, Clark Field, etc.

An astonishing testament to the power of consensus to make the implausible the unquestionable. Can a human “terrorist” trained in a flight simulator, let alone an experienced pilot who usually relies on runway lights and paint, really hurl a passenger jet into a specific building on an erratic path like this? — computer-controlled flight, the reader may not be aware, was already a half-century old technology by the time of 9/11.

If we return to the observation that conspiracies make sense of the world, what seems to explain the death of 9/11 trutherism is that it fails to help make sense of reality for either Republicans nor Democrats — it does not offer an explanation for why things are “wrong.”

One almost might say it cannot offer such an explanation, because it is incomprehensible. The day and its events have from the start borne the character of a sacred spectacle, a violence beyond comprehension — they were to American society what being captured and eaten by a predator is to the mouse. The tenuousness of the social consensus of reality being laid so bare — no one knows why this is happening — demands not seeing the conspiracy, but ignoring it. Instead, it is the mainstream narrative that, from the start, offered to make sense of the world — America was the cat, Islam was the mouse. From the confusion of being the object of violence, American society sought an object upon which to wield violence.

But this isn’t really the point. It is more that all alternatives to the mainstream narrative surrounding 9/11 cannot be said to have retained any political or social salience to the present except in the meta-sense — the sense in which doubting the narrative explains what is “wrong” about society simply because 9/11 was a conspiracy of some grand fashion. But this is a useless function, as individual tendency to believe in conspiracy theories, again, is entirely symptomatic of personal conflicts with society — it doesn’t depend in any way on “evidence” that conspiracies have really happened throughout history.

With no obvious contribution to “making sense of the world,” 9/11 can only reveal how impossible it is to do the same. The individual is always powerless to prevent society from believing in false truths, from becoming wed to evil notions, from changing — for society itself is the agent of conspiracy. At all moments, it is an entity manufacturing arbitrary consensus with no obvious relationship to previously-agreed-upon goods.

One which I remain skeptical of — see “The lab leak addiction.”

See “The Origin of Lockdowns.”

Source: Unglossed

Comments

Post a Comment