The Revolt of the Somewheres

The Revolt of the Somewheres

National populism as a response to Anywhere arrogance

The French economist Thomas Piketty has a real gift for assembling data. His Merchant Right versus Brahmin Left analysis is an enlightening analysis of postwar Western electoral politics post the expansion of higher education.

Parliamentary/representative politics have a long history, dating back to the late C12th. The industrial revolution’s factory and office employment not only separated production from households. Men worked and networked together in increasingly urbanised societies. The shared experience, denser connections and expanding mass communications led to mass politics 1 and agitation for expanded suffrage.

As democratic politics developed, the main divide was between lower-income, lower-asset folk (“labour”) on one side of politics and higher-income, higher-asset folk on the other (“capital”). With the development of mass higher education and pervasive bureaucratisation in the postwar era, politics in developed democracies has since been dominated by the possessors of human-and-cultural capital 2 (the Brahmin Left) facing off against the possessors of commercial capital (the Merchant Right).

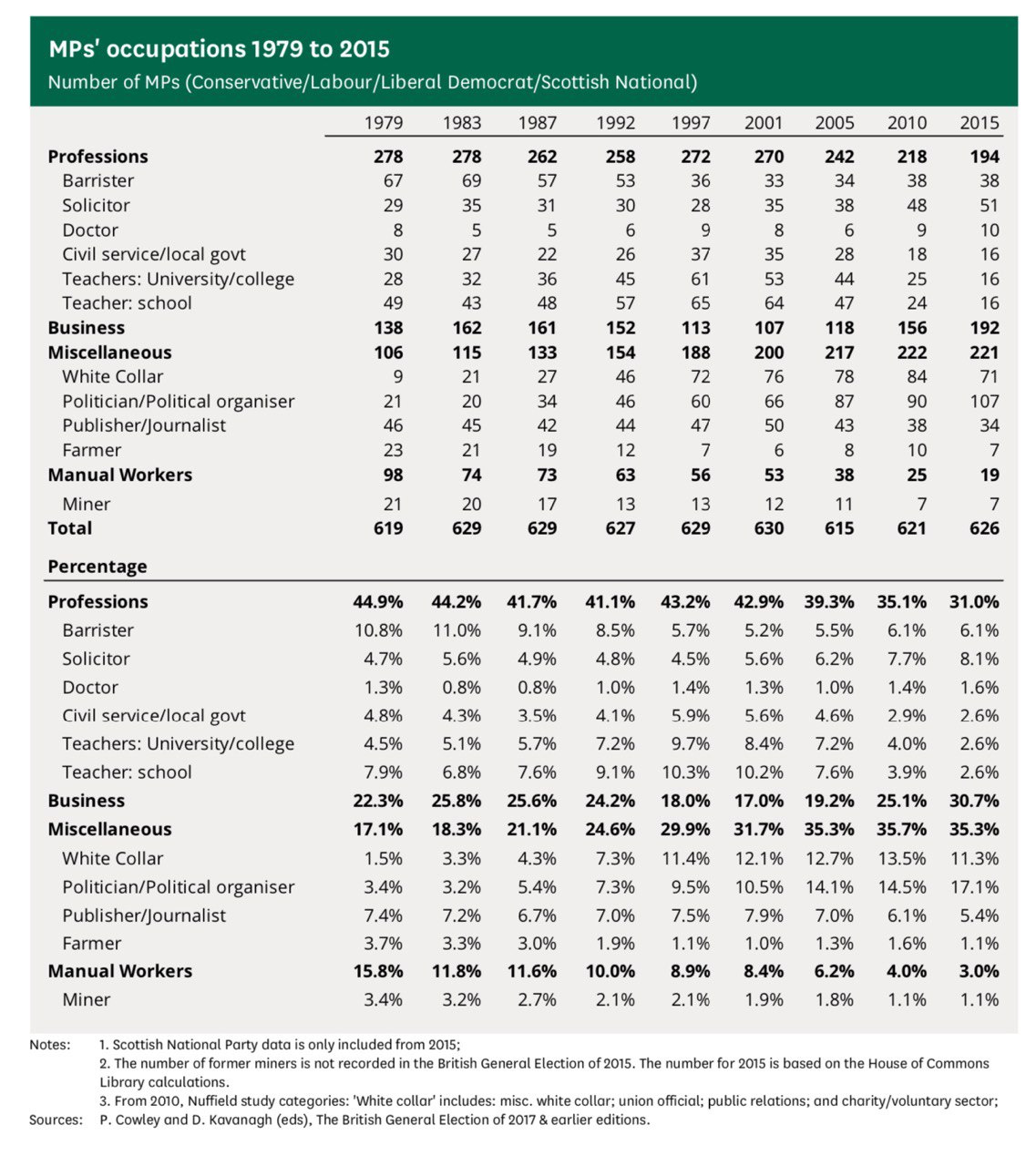

The working class has been squeezed out of active political participation—literally so in the House of Commons, which has seen the number of MPs with working-class backgrounds dwindle.

This divide between different types of capital 3 interacts uneasily with another social divide. That divide—to use social analyst David Goodhart’s formulation—is between progressive Anywheres (around a quarter of the population) and locality-centred Somewheres (around half the population). That is, folk whose professions and connections are not anchored in a particular locality—and have networks that regularly cross national boundaries—and those whose lives, jobs and connections are much more centred on their local communities.

The latter are mainly working-class folk, but also include locally-based businesses and professionals. The former include both the human-and-cultural capital class and “big end of town” commercial capital.

Various types of Anywheres overwhelmingly dominate most organisations and institutions, including the political class (politicians, staffers, activists) among both Brahmin Left and Merchant Right. This leaves the Somewheres largely unrepresented by—and somewhat alienated from—institutional politics.

Meanwhile, the most hyper-progressive Anywheres dominate the epistemic industries (academe, IT, entertainment, media). This leaves Somewheres cut off from the process by which societies talk to themselves.

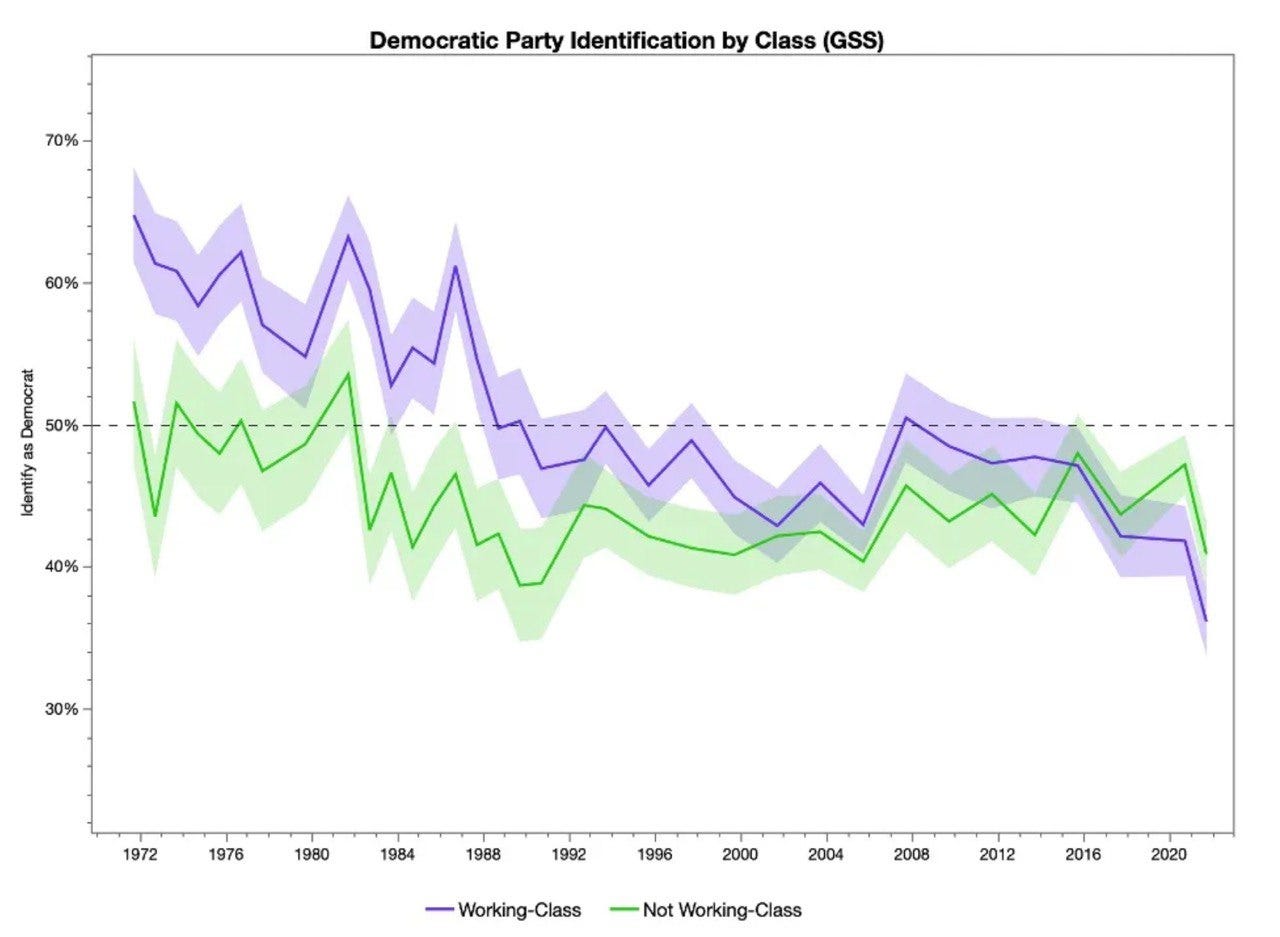

The shift from the primacy of economic issues (labour v capital) to the primacy of cultural issues (Anywheres v Somewheres) has seen working-class voters drift rightwards: they tend to be economically radical but culturally conservative. This pattern emerges from the centrality of risk-management concerns to working-class families and households.

Working-class voters typically want the state to buffer them against economic shocks and pressures. 4 They also want stable local communities—safe for their families—so their locality-based connections (their social capital) can better enable them to manage and respond to events, risks and opportunities. 5

“Swing” votes are not those with “median” political views. They’re often left wing on economic issues and conservative on social issues, switching their votes depending on which is more salient. The common element in this “odd” pattern is risk management: protection from both market vagaries and social disorientation.

The UK has experienced a particularly dramatic political sorting because Brexit made both cultural and economic cleavages salient at the same time. So, using the model and labels developed by Steve Davies and Helen Dale we can see a Brahmin Left divided into the younger, more radical-progressive, Anywheres (Radical Remainia) and the older, more settled (and liberal) Anywheres (Liberal Remainia). Then there are two bastions of patriotic feeling: business and professional Somewheres (Brexitshire); and the culturally conservative, economically redistributive, Somewheres (Leaverstan).

Trump’s Presidential candidacy divided US politics similarly. The Republican Party’s attempt to bridge country-club business Republicans (who dominate their donor base) and a growing number of working-class Republican voters has much to do with why it has been producing theatrical politics—with hyper-elevated rhetoric—to cover for its policy contradictions and paralysis.

Meanwhile, in Europe…

What the EU (as it became) has done for democracy in Europe is simple. You have to be a democracy to be a member and there are substantial trade benefits from membership. 6 That is what the European Economic Community (EEC)—for which British voters voted so strongly (67% to 33%) in the 1975 referendum—provided.

To have made democracy Europe’s default politics and to build a structure that rewards democracy—while entangling members with other democracies—represents genuine achievement.

But the EEC evolved into the EU. The Common Market evolved into the European Project of Ever Closer Union. The European Project was what a majority of British voters rejected in 2016. The European Project does not do more for democracy than what the Common Market already did. On the contrary, it evolved in ways which prodeces net subtractions from democracy. “EU agreement” can be used as a weapon against domestic critics.

In the UK case, EU membership drove up food prices, made Britain the largest net contributor to the EU budget, slowly undermined the English common law and state capacity (it degraded the civil service’s skills base and accountability) and undermined border control.

Any notion that history has a rightful direction—to which right-thinking folk are committed—means citizens are not to be served but are instead human clay to be moulded. Much of the appeal of such a belief is precisely the coordinating, social-leverage and social-status advantages we-are-the-rightful-elite notions provide.

Democracy requires that there be more than one legitimate outcome. When history has a “rightful direction”, it implies there is only one legitimate outcome, whence the incompatibility.

There is a fundamental problem built into the EU’s origins. That was to rhetorically identify nationalism—a popular sentiment—as the great problem of European history. This creates a rhetoric that de-legitimises “incorrect” voting and votes by wrongly-feeling voters. It does so even more strongly when added to the Hegelian project of Ever Closer Union.

How does one vote against Ever Closer Union? Only by leaving.

Accountability and political bargaining

The identification of nationalism as the central problem of European history is false. The real problem of European history is unaccountable power. Yes, nationalism can be—and has been—mobilised by power without accountability.

Pursuing a victorious war to fight off demands from within one’s polity for various folk to have more of a say—for ruling groups to be more accountable—proved to be an enduring, even catastrophic, illusion. National glory as a barrier to increased accountability led to the Dynast’s War of 1914-1918, and the fall of the Romanov, Habsburg, Hohenzollern, and Ottoman dynasties. All found themselves trapped in, and then destroyed by, the dynamic of total war.

Nevertheless, lack of accountability is the central problem. Europeans have found plenty of reasons to massacre each other that have nothing to do with nationalism.

The great irony is that unaccountable power generated destructiveness throughout European history precisely because European civilisation developed historically unprecedented levels of accountable power.

Early medieval Latin Christendom’s sanctification of the Roman synthesis: law-is-human (i.e., not based on revelation); single-spouse marriage; no kin-groups (including via personal wills that broke kin-group control over intergenerational transfer of property); no cousin (or other consanguineous) marriage; female consent for marriage—let loose a process of institutional experimentation.

As an array of social arrangements replaced what kin-groups did in other societies, a variety of institutional structures were created that super-charged the process of evolving effective institutions. The selection processes of history—operating among intensely competitive states—had far more variety to work with than in any other civilisation.

As political and social bargains could be entrenched in law—and the medieval development of the representative principle meant that deliberative assemblies could be scaled up—bargaining politics grew and became entrenched. Over time, bargaining politics began to evolve towards turning state apparats into what they are so often not: agents of their society and the interests therein.

Endemic warfare between European states created pressures towards broader political bargaining so as to better mobilise resources, and so be more militarily effective. The fight-for-one’s-polity, so-have-a-say-in-it, dynamic also created the citizen-polities of the Classical Mediterranean, which led to the Roman synthesis. Giving citizens a say in the politics of their city-state made them much more willing to invest in equipping and training to fight for their city-state. It created tough, committed (through generally small) armies.

Only Rome was willing to “scale up” its citizenship. That willingness—along with developing a flexible and effective military system—took it to dominion over the entire Mediterranean world. Medieval Europe added the representative principle—merchants and knights/gentry electing representatives to Parliaments—enabling bargaining via deliberative assemblies to be scaled up.

The political bargaining rights people had in one place contrasted with what others did or did not have in others. The upward spiral of bargaining politics is why various forms of national identity developed unusually strong resonance in Europe.

Yes, almost every single national identity is a composite of more localised ethnic identities, composites that arose via historical processes. Nevertheless, bargaining politics naturally led to the political nation.

Observing what happened in other polities—and who was in or out of the bargaining circle in your own, even what language bargaining was done in—all helped to make national feeling unusually politically resonant.

National feeling was not an invention of the French Revolution or the c19th.7 What

did develop then were new ways of mobilising national feeling using mass communications. This naturally favoured organising within specific languages.

The soft landing for post-imperial state apparats

The EU can seem to be part of this process of expanding political bargaining, but is actually a narrowing of it. The European Parliament provides a facade of accountability, not the real thing. Declining voter participation in its elections indicates lack of confidence in its utility as a mechanism for political bargaining.

The real value of the European Project to the state apparats of post-imperial nations has been to provide a replacement administrative layer for that previously provided by imperial rule. State apparats can, and do, colonise upward into supranational bodies as a replacement for colonising outward via territorial imperialism. The welfare state represents them colonising inwards.

Driven by its founding rhetorical fear of “wrongful” popular sentiment, the European Project has developed new structures of unaccountable power than can be used to undermine democratic accountability. This comes about partly by duck-shoving responsibility for policy between EU and national governments, partly through decay of underused national administrative capacity, and partly through over-riding the wishes of local electorates.

It is thus less than surprising that the Europhile elite has something of a history of de-legitimising inconvenient referendums and has proved clumsy at responding to popular concerns. In the case of the UK, over four decades of experience of what became the EU had turned a two-thirds vote in favour of membership in 1975 to a majority vote to leave in 2016.

It is typical of Europhile politics that there has been little or no attempt to understand how being in the EU managed to do that, or to look for any failings within the European project. Such are, apparently, wrongful noticings.

Instead, Europhile commentary has been directed to attacking citizens who voted Leave, to de-legitimise their perspectives and their votes.This absolutely fits in with the notion that the fundamental problem of European history is “wrong” popular sentiments—with the EU, and particularly the Europhile Anywhere elite—as a “solution” to the same.

If, as critics allege, voting for Brexit was a morally and cognitively degraded choice, then apparently 40 years of EEC-to-EU membership increased the moral and cognitive degradation of British voters. Especially as older voters were more likely to vote Leave: those who had most experience of the EEC-to-EU were most likely to vote to leave it.

Treating the Leave vote as a morally and cognitively degraded choice is an arrogance that many folk were only too willing to embrace. It also avoided thinking through what that implied about the European Project itself.

You can still make an argument that the EU is a net boon to democracy. The European Project of Ever Closer Union is not. Did the voters ever vote for Ever Closer Union? At what point to they get to vote to stop Ever Closer Union? The answers so far are not really and apparently never—except by leaving.

So, we have a Europhile elite that tends to undermine accountability, that regards itself as knowing the proper direction of history, that is entitled to judge the voting of citizens on that basis. This is not a solution to the problems of nationalism. It is an invitation—and provides a set of incentives—to reinvigorate the politics of nationalism.

Re-invigorating nationalism

National populism in established democracies 8 is a reaction by Somewhere voters excluded from political bargaining dominated by Anywhere elites. And Anywhere elites have used the EU as an extra instrument of Anywhere policy dominance.

This is all without delving into the madness imposing a common currency and single monetary policy on divergent economies.

While one can find plenty of examples—such as driving up rents and house prices by using zoning to restrict housing supply or using mass migration to break up local communities and their embedded social capital—three notable examples of Anywhere elites screwing over Somewheres are as follows.

In the US, there was BLM and Defund the Police. In Europe, there was the betrayal of vulnerable women and girls in Muslim-dominated localities. Finally, economic devastation was levied on ordinary Greeks to protect Franco-German banks from the consequences of their bad loans—loans entered into on the basis of systematic deceit by elite Greek politicians.

Across Western democracies, Somewheres confront in Post-Enlightenment Progressives (the “woke”) the most future-worshipping Anywhere group. These Anywheres systematically devalue cultural heritage, devalue the legitimacy of Somewhere concerns, and devaluing Somewhere voting through the non-electoral politics of institutional capture.

The salience of non-profits in the US political system (due to adversarial legalism)— along with its mass universities—means that these patterns have been particularly intense in the US. A process that ramps up from 2010 onwards 9 as a combination of:

1. Barack Obama’s election causing a crisis for conceptions like “the US as permanent KKK state” 10, especially among the African-American “vampire elite”—whose social leverage comes from framing the US as the oppressor of their ethno-racial confreres.

2. A collapse in the media’s business model led to a “go broke go woke” pivot that takes in using identitarian terms to emotionally engage readers while deploying the Pravda media model, where those readers are told what the smart and good people believe.

3. Feminisation of the academy, professions, and institutions, which undermines free speech norms and increases moralised aggression (often mean-girl mobbing). This is coupled with demands to trade in other folk’s freedoms and careers to protect highly educated women’s feelings.

4. Aggravating features of social media—like and share/retweet/repost buttons—turbocharging mobbing, as seen in Shirtgate and Gamergate.

I don’t have much sympathy for authoritarian or ethno-nationalist politics of any stripe. My concern is the reverse. The vicious fools of progressivism—who know (sic) the right direction of history—are feeding the ethno-nationalist, authoritarian-reaction beast, as they have done before.

This is a pattern of failure from which they are apparently unable to learn, because shielded by fables of progressive innocence. There is no pattern of action and response, just the “true evil” of the Right flowering forth. This is a ludicrously ahistorical—but utterly self-exculpating—outlook.

But how can they learn? They are such a moral and cognitive elite. If you think otherwise, you are moral dross who notices wrongly. The dynamics of this are explored further in the next essay.

—

References

Books

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Prey: Immigration, Islam, and the Erosion of Women’s Rights, HarperCollins, 2021.

Gregory Clark, The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility, Princeton University Press, 2014.

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion, Pantheon Books, 2012.

Eric Kaufmann, Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities, Penguin, 2018.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Stephanie Muravchik, Jon A. Shields, Trump’s Democrats, Brookings Institution Press, 2020.

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States, Free Press, [2010], 2011.

Stephen Smith, Pagans & Christian in the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the Potomac, Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2018.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

Articles, papers, book chapters, podcasts

George Borjas, ‘Immigration and the American Worker: A Review of the Academic Literature,’ Center for Immigration Studies, April 2013.

Laura E. Engelhardt, Daniel A. Briley, Frank D. Mann, K. Paige Harden Tucker-Drob, ‘Genes Unite Executive Functions in Childhood,’ Psychological Science, 2015 August, 26(8), 1151–1163.

Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´inez-Toledana, Thomas Piketty, ‘Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages In 21 Western Democracies, 1948–2020,’ The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol. 137, 2022, Issue 1, 1-48.

Zach Goldberg, ‘How the Media Led the Great Racial Awakening,’ Tablet, August 05, 2020.

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/media-great-racial-awakening.

Mark Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233.

Ryan Grim, ‘The Elephant in the Zoom,’ The Intercept, June 14 2022.

Jonathan Haidt and Jesse Graham, ‘Planet of the Durkheimians, Where Community, Authority, and Sacredness are Foundations of Morality,’ December 11, 2006. https://ssrn.com/abstract=980844.

Rob Henderson, ‘Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class—A Status Update,’ Quillette, 16 Nov 2019.

Henrik Jacobsen, Kleven Claus, Thustrup Kreiner, Emmanuel Saez, ‘Why Can Modern Government’s Tax So Much? An Agency Model Of Firms As Fiscal Intermediaries,’ NBER Working Paper 15218, August 2009.

Robert A. Kagan, ‘Adversarial Legalism and American Government,’ in Marc K. Landy and Martin A. Levin (eds), The Politics of Public Policy, John Hopkins University Press, 1995, 88-118.

David C. Lahtia, Bret S. Weinstein, ‘The better angels of our nature: group stability and the evolution of moral tension,’ Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 2005, 47–63.

Stephen Leslie et al, ‘The fine scale genetic structure of the British population,’ Nature 2015 March 19; 519(7543): 309–314.

Jacob Mchangama, ‘The Sordid Origin of Hate-Speech Laws: A tenacious Soviet legacy,’ Hoover Institute, December 1, 2011. https://www.hoover.org/research/sordid-origin-hate-speech-laws.

D. Rozado, R. Hughes, J. Halberstadt, ‘Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with Transformer language models,’ PLoS ONE, 2022 17(10): e0276367.

Manvir Singh, Richard Wrangham & Luke Glowacki, ‘Self-Interest and the Design of Rules,’ Human Nature, August 2017.

Peter Thiel, ‘The Tech Curse,’ Keynote Address, National Conservatism Conference, Miami, Florida, September 11, 2022.

Daniel Williams, ‘The marketplace of rationalizations,’ Economics & Philosophy (2022), 1–25.

The pioneer secular mass political movement was the British abolitionist movement, the first of what became Europe’s Emancipation Sequence — anti-slavery, Catholic Emancipation, Jewish Emancipation, adult male suffrage, woman suffrage, civil rights, etc.

Sometimes referred to as the managerial class or the professional and managerial class. I prefer a term that has much wider historical resonance.

Capital = the produced means of production. That the same term is used for aggregated payment capacity (‘firm capital’)—particularly the ability to cover loss—is not conducive to clear thinking.

One of the uglier behaviours in modern politics is those shielded from the vagaries of markets by their wealth sneering at folk who lack such shields.

What works in social milieus where most people have generally high executive function can very much not in social milieus where most people have less executive function. Executive function is extremely heritable—it’s probably a significant reason why social mobility is relatively low across human societies—and so also generates a considerable amount of smug condescension among Anywheres.

Comparison of shifts in the relative share of world GDP between the US and EU suggests that the EU’s economic benefits are oversold. The “upward” colonising of the EU bureaucracy imposes significant economic costs: e.g. through regulatory cartelisation.

The first nation state was pharaonic Egypt. Egyptians had a strong sense of their different ethnic identity from the folk around them. They engaged in “bloody foreigners” national-identity rhetoric denouncing the Hyksos over three and a half millennia ago. The Greeks argued over who was, or was not, a Greek, as only freeborn Greek men could compete in the Olympic games.

National populism in Eastern Europe has somewhat different dynamics. Democratic norms are less established and the 1989 revolutions had a strong element of assertion of national identity: including against the cultural imperialism of EU elites.

What conservative commentator Steve Sailer regularly refers to as “the Late Obama Age collapse”.

Andrew Sullivan’s evocative phrasing.

Comments

Post a Comment