Is it legal?

Is it legal?

On laws, authorities, and superstition

During the personal lockdown my poor health imposed on me, I became so depressed I could hardly read anything more complicated than a cake recipe. That’s when I found what I call “the bottom of the Internet”: pages whose main business is reproducing idiotic Reddit tales, interspersing them with inane text that more or less paraphrases the original story so that there is some “original” content to shield them from accusations of copyright violation.

Two kinds of stories are often republished at the bottom of the internet: familial woes, and workplace problems. The kind of thing that in regular fiction or news (even if most news is fictional nowadays) would provide no more than a background. Great fodder for depressed Thomist sociologists temporarily unable to face organized studies of what, in the end, is the same subject matter. The few neurons still alive in my brain, of course, would often spark a connection and let me know that this or that was a good example of something somebody wrote about in theoretical terms, but that was not the point. I just needed to live vicariously through all that small stuff while lying down and trying to find a position that would hurt less.

Now, the social and psychological function of good fiction is precisely that; it allows people to live what they otherwise wouldn’t, and thus learn about the world outside without risking life or limb. But good fiction has good plots, cliffhangers, character development, and other stuff requiring a functional brain to be enjoyed, while the silliness of microwave-reheated Reddit tales is “easy reading”, in the same sense as elevator music is called “easy listening”.

Anyway, my few remaining neurons would sometimes keep tugging when some tale was too good an example of something just to let it pass. That is why I decided to try writing something this morning after I woke up feeling better than the recent average. The triggering publications, lost forever in the vastness of my browser’s history, are two. One was an anguished post by an Englishman about to get married, and the other a complaint by a Canadian, if my memory doesn’t fail (as it regularly does), about a common internet misunderstanding. Let’s start with the latter, as it is shorter:

The good Cannuck mentioned that he would often get comments on his publications asking whether it was legal to do something he had written about. He’d say it was, and for him, it was obvious that in a story that began with “Here in Ontario”, or something like that, the commenter would be asking about local Canadian law. But more often than not, it would be an American who assumed American law was valid in Canada, and until the misunderstanding was solved a quite long nonsensical back-and-forth of comments would take place.

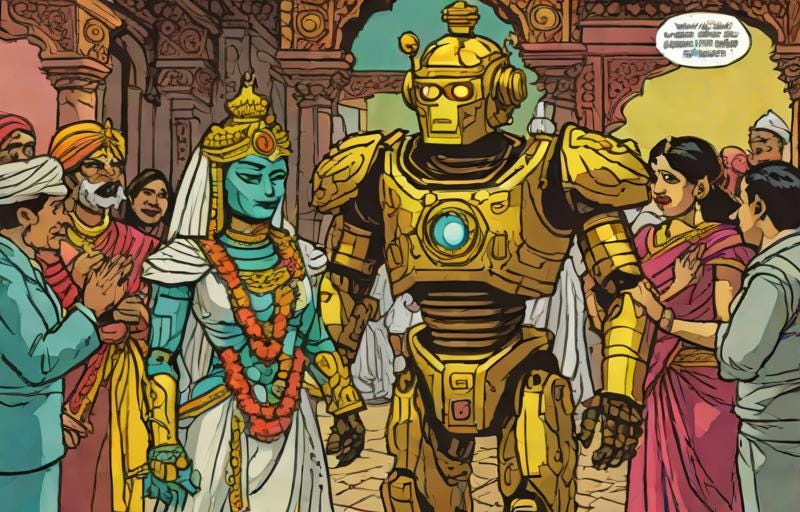

Now the Englishman’s tale is much juicier, insofar as this kind of background noise to real life can be juicy. He was about to get married to an Indian Muslim girl, and a cross-cultural misunderstanding shocked him so much that he was asking people on Reddit whether he should break up with her. The saddest part is that he had not understood it was a textbook case of cultural misunderstanding. He took his culture’s values for granted, and could not understand that radically different cultural values informed his fiancée’s view of the same situation.

As the guy told it, his fiancée wanted to have a big fat Indian wedding, and he went on with it. However, a friend of his who had also married an Indian Muslim lady in a simple civil ceremony told him that as much as his bride wanted to have a more traditional wedding, they couldn’t have had it because he was not a Muslim. As the groom-to-be wasn’t a Muslim either, he couldn’t understand how he was going to have the very same over-the-top traditional ceremony his friend was denied. Drama ensued when he asked his fiancée how it worked.

The young lady laughed and said there was no big deal: he just needed to say some magic words (the Shahada: "I bear witness that there is no deity but Allah, and I bear witness that Muhammad is the Messenger of God") in front of some Muslim authority figure immediately before the ceremony, and he would have become enough of a Muslim to marry her in a traditional ceremony. No big deal, she said; he didn’t need to follow through and live as a Muslim, there were no Catechism classes or anything like that required. He just needed to blurt out that nonsense once, and presto: they could get married the traditional (for her) way.

To say the poor Englishman was shocked would be a very British understatement. He was floored. Devastated. He didn’t want to become a Muslim! His fiancée, on the other hand, couldn’t understand what was the problem. After all, he was an atheist anyway, and of course, he would stay an atheist. He wouldn’t be abjuring any (other) faith. It was just an empty ritual, a bureaucratic part of the marriage process. He couldn’t understand how she was taking it so lightly, and she couldn’t understand why he was making a mountain out of a molehill.

The core of that cultural misunderstanding is very simple: the Englishman belongs to a thoroughly Modern culture (it could also be said that he belongs to the Modern culture, as Modernity seeks to replace all other cultures) and thus adheres to superstitions that virtually any other culture in the world would see as weird and foolish. And here is where, at last!, the posts that triggered these ramblings meet. The main superstition of Modernity can be summed in the absurdly wide scope in which the question “Is it legal?” makes sense for Moderns.

In any regular culture, this question has a very limited purview, and will only make sense within bureaucratic endeavors of some kind. Accountants care whether stuff is legal, for instance, but regular people will never hear or ask that question in their lives. Its equivalent outside of Modernity would be something akin to “Am I allowed to do it?”; the fact that both questions seem to mean the same thing in Modern culture is at the root of many cultural misunderstandings, such as in the Englishman’s marriage process.

The root Modern superstitions at the core of the problem are:

The belief in the top-down organization of society, that is, the presumption that government and its laws (especially the State Constitution) somehow create (“constitute”, establish) society and societal morality;

The belief in the impartiality and impersonality of governmental systems and authorities.

The first belief above has many corollaries, among which the confluence of “Is it legal?” and “Am I allowed to do it?”, questions whose meaning and importance are completely different in any non-Modern culture. When one believes that formal institutions of power create a society, human law substitutes for both morality (from “mores”, customs) and, quite often, reasonableness. While “Am I allowed to do that?” implies “Is it acceptable social behavior?”, “Will it have unpleasant consequences?”, “Will doing it annoy someone whose wrath I must avoid?”, and so on, “Is it legal?” restricts the question to a binary informed by (theoretically universal across a given society) human laws.

In Modern societies, however, the production of laws vastly outperforms the output of all other industries combined. In the common Modern tripartite division of powers, the function that directly employs the greatest number of people at its top level is that of lawmaker. While there is usually one head of the Executive and a body of less than twenty people at the head of the Judiciary, the Legislative body usually counts at least a few hundred members. It is intentional, as society, in the Modern belief system, would be created and perpetuated through the creation of laws (instead of through the constitution of families and voluntary associations).

Consequently and predictably, even if we leave aside that most “laws” are nowadays made through Executive regulations, the sheer number of laws makes it impossible to assume that doing what everybody else does will keep one within the boundaries of what is legal. Hence the notorious question “Is it legal?” When we add to the equation the Modern confusion of human law and morality, which makes it perfectly acceptable to be a pest and a nuisance as long as what one does is “legal”, living in society becomes a game in which the boundaries of acceptable behavior depend on hidden knowledge. One of the most popular Reddit forums (“subreddits”) among Reddit-tales curators is called “Malicious Compliance”, by the way. It consists of tales in which a sorcerer apprentice regular guy follows to the letter some human-made law to get revenge against a knight of the Dark Side bad boss or landlord.

And here we are back to the poor British groom. Anywhere outside Modern society, authorities are seen as people who can make one’s life miserable if crossed and therefore should be avoided or placated. That’s what informed his fiancée’s plans for their marriage: the Muslim cleric would ruin their wedding unless placated by the recitation of some nonsensical formula, so she just added that recitation to their to-do list and thought no more about it.

The groom’s view, however, was the opposite. His Modern beliefs lead him to have a very strong taboo against telling fibs to authority figures. He could either shut up or say “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth”, and he certainly couldn’t care less about Muhammed, Allah, or Snow White and the seven dwarfs. In American movies, policemen who arrest someone have to perform a ritual in which they solemnly state that the person arrested has “the right to remain silent” and that whatever he says can be used against him in court. The taboo against telling tall tales to authority figures is so strong, though, that nothing is said in the ritual words about his right (or lack thereof) to lie.

Another funny Modern ritual is clicking the button “I agree” when installing software. Nobody reads the mountain of legalese one would be theoretically agreeing with, and it is an intellectual impossibility to agree with something we do not know. I’ve heard of software developers who hid in their legal mumbo-jumbo a promise to pay a certain amount of money to whoever wrote them telling them they read the thing, but I’ve never heard of developers having had to pay more than one or two dung-reading madmen. Nevertheless, Modern societies consider those ludicrous non-agreements binding.

The main difference between the cultures of the bride and the groom is that in hers her loyalty lies with her family (including, of course, her beloved groom), and whatever one says on its behalf to placate an authority that is seen as a dangerous outsider is worthless. For him, it’s the opposite: his marriage’s very existence issues from some formal authority of which the Muslim cleric would be a representative, not from the groom and the bride. The top-down model of society he adheres to makes formal authorities at least necessary mediators between people, and ultimately the source of ties such as that of marriage. This is the superstition that makes divorce possible, for instance: after all, a connection created by the State can be annulled by the same State.

The pervasiveness of State power in Modern thinking makes it a substitute for God. However, unlike the real God, Who is unchangeable, the Modern State is a work that is perpetually in process. There will not be a time when lawmakers will decide they created (from nothing) enough laws, and can close shop. It is a consequence of the fundamental inversion of truth that lies at the core of Modernity; when Descartes decided that he could not be certain that the real world around him existed, but his own existence could be proved by the fact that he was thinking, he subverted (and perverted) the perception of reality and truth. Truth is the agreement of our mental perception to the real thing outside our mind, in the real world: if I hold an orange and recognize it is an orange, my perception is true. If I mistake it for something else, it’s not. Thus, the touchstone one uses to check whether one’s thoughts are truthful is reality itself.

Descartes inverted it, and in Modern thought the idea becomes the touchstone of reality. That is why all ideological thought starts with an idea of what society should be and tries to make the thing agree with the idea. It’s a kind of magical thinking, insofar as no human mind could possibly apprehend the whole of reality or even the whole of a given human society. In societal terms, it means that new laws must be created all the time so that reality has something to cling to.

For the Indian bride, becoming a Muslim entailed much more than pronouncing a few words. It meant believing in Allah and submitting to whatever Mohammed and his successors said one must submit to (“Islam” literally means “submission”). It meant praying five times a day, eating only approved food, and so on. No magic formula hastily pronounced so that one can get a nice wedding could conceivably change reality and make a real Muslim out of an English atheist.

In her fiancé’s magical thinking, though, it was possible to be hexed into a Muslim, just as it would be possible to commit an immoral act by doing something one honestly never knew was “illegal” or violating a software-installation non-agreement. It is akin to pharisaic thinking, in which one can sin by accident (for instance, eating something one did not know contained pork), with no intention of sin. The poor man truly believed, from the dark bottom of his superstition, in the magical power of the incantation he would have to utter, and he did not want to become a Muslim.

Despairingly, he saw his loving bride as Snow White’s witch stepmother, who gave her a poisoned apple, without realizing that he was the one providing the poison when he read her actions through the prism of his own (Modern) cultural values. She honestly didn’t know about the Modern taboo against placating authority figures with harmless fibs, she honestly could not imagine that he would attribute the ritual recitation of some nonsensical words so much power. She couldn’t know.

I don’t know what eventually happened to the couple, but I know that if he didn’t break her heart and they stayed together it would be just the first of many other cultural shocks and misunderstandings. After all, the all-powerfulness Muslims attribute to their Allah is still much smaller than the reality-creating that Moderns attribute to their formal institutions. It is quite probable that someday her husband would put the State between them, as he already believed that the State (not them) performed (instead of recognized) their marriage.

This is the same superstition that is at the core of the common right-wing fear that the Left will “destroy the family”, as if such a thing was possible. They believe the State (which can very well be in the hands of the Left) creates families through its rituals and therefore could destroy the very institution of the family in a similar way. Their belief that the Modern State — a very recent and geographically limited institution, by the way — is a creating god that generates society doesn’t allow them to understand that all it can do or cease to do is recognize what was there much before it and will be there long after it’s gone.

When human laws call “marriage” any other kind of union between human beings (or even between human and non-human beings, as there are alternative kinds of lunatics trying to “marry” bridges and dogs), all it does is muddle its convenient, albeit unnecessary, recognition of preexisting families. It is certainly not creating “new kinds of family”, just as if a child decides to call apples oranges it is not somehow creating a new kind of orange.

Human laws cannot create realities. All they can do is provide incentives for human action. If the laws are enforced by State power, the penalties will be a negative incentive, and that is it. New laws cannot change what is right and wrong; all they can do is threaten those who do what they forbid or even force people to do wrong under duress. “Is it illegal?” is not a question about ethics or morals, only about the possibility of being harassed by Modern formal institutions.

And, of course, no ritual incantation can transform an English atheist into a Muslim.

Chesterton was right: when people stop believing in God, they will believe all kinds of nonsense.

Source: A Thomist Worldview

Comments

Post a Comment