How to Orient an Organism

How to Orient an Organism

Understanding Depression, Collapse, and Triumph

Emerging from primordial musical chaos, light dawns on a new Earth, and we see the title card The Dawn of Man. A tableaux unfolds in which semi-erect apes get attacked by leopards, hunt with their bare hands, and fight wars over access to water, before inspiration strikes—perhaps sent by the gods—and one curious ape makes a connection between the way a discarded bone knocks other discarded bones around, and the usefulness of that bone as a weapon. Smashing the bones around him, the ape works himself into a state of triumphant, orgiastic glee. He takes the bone and uses it to defeat the rival tribe, hunt game, and rule his small corner of the world until, in a celebration of triumph, he throws the bone up into the air, where a quick scene change lands us in orbit above the Earth, traveling alongside spacecraft, space stations, and weapons satellites.

The first tool in the conquest of the Earth, to the first tools in the conquest of the universe in one, stunning step—or, perhaps, one giant leap.

Consider, however, another tale:

A man lives in a world that keeps him stimulated but leaves him numb. He’s unsatisfied in his stable-but-boring job, but it gives him the means to seek spiritual fulfillment in his second life as a hacker and illegal files-dealer.

When he learns that his own hacker life is but an echo of the realities of a higher universe—one where his physical body is plugged in to a series of computer interfaces—he learns that he can use this secret knowledge to control the laws of the world that he’s plugged into.

In the real world he uncovers, he’s a gangling naive newbie living with a band of impoverished outlaws. In the artificial world, he is a god who can bend the universe to his will while being the sexiest geek in the game.

The first of these scenarios is from the 1968 science fiction cinematic masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. The second is from the 1999 Gnostic cyberpunk film The Matrix. There is a lot going on in both of these films, but for our purposes, when we set the attitude of one against the other where technology is concerned, it reveals a fissure that divides humanity and casts a stark light on some key questions of our age:

Why are modern people so depressed?

Why do rat utopias collapse?

Why do civilizations fall?

Big questions, but, strange as it sounds, they all have the same answer, and it’s not the answer you’ve been sold…by anyone.

Technological Revolutions

That opening scene in 2001 is depicting a mythic version of the first prehuman technological revolution: a new tool is discovered, and the propagation of that tool changes everything about the society into which it is introduced.

Forget what you’ve heard about the “neolithic” revolution, the various “industrial” revolutions, and so on. These are basket terms that historians and teachers use for convenience. They massively undersell the way that a single invention can alter reality. And, ironically, the more obviously impressive an invention is, the less of a long-term cultural effect that it tends to have.

Supersonic flight is an astonishing achievement, but its effects on the world (impressive as they’ve been), have been minuscule compared to another invention from the same period: the Lithium-ion battery.

Both inventions date from the post-war period (late 1940s-early 1960s). Supersonic flight changed the way that aerial combat was done, which had knock-on effects for warfighting strategy. Lithium-ion battery chemistry, on the other hand, made portable communications practical, sending ripples out through our socialization, politics, dating, sexuality, economics, electronics, and is now (thanks to its use in drones) precipitating a worldwide combat revolution that may, in the long run, prove to be as dramatic as the discovery of gunpowder or steel.

The more general the invention, the more it changes what it means to be human.

In 2001, technology expands human power—almost spinning out of control and superseding us in the same way that a child will extend the life-line of and can destroy his parents—providing a force multiplier to human effort in a way that opens new horizons.

A force multiplier is, in its most basic sense, a machine that focuses energy. You can’t punch through a car window—breaking tempered glass requires a force of several hundred Pounds per Square Inch. An average adult male delivers a punch loaded with between a hundred and a hundred fifty PSI. Since business-end of a human fist is only two-to-four square inches, the blow for a good hard punch (assuming you’re not a ripped boxer) is somewhere around three-to-five hundred pounds of force, total.

There’s no way you’re punching through a car window, even to save your life.

But consider this weird feature that is now common on the lowly pocket knife:

That little steel nub sticking off the butt end of the knife is called a “glass breaker.” Take the closed knife in your fist and pound against a car window, the window will break even if it’s holding back tons of water. All five hundred pound of glorious punching force meets the tempered glass at a point a few microns across, giving your strike an effective force of a few thousand pounds per square inch. Your delivery force has been multiplied—and, if you’re in a car sinking below the water, your life gets saved in the bargain.

The Matrix, on the other hand, does not view technology as a force multiplier that extends human power in the real world. In the world of The Matrix, taming reality is far less important than escaping it—even the war against the machines to save the human race is conducted mostly inside the simulation, and the ultimate resolution to the great conflict (at the end of the third film) is that those who want to leave, can, but it is clear that most people simply will not.

And why would they? The dream-world is set “at the height” of human technological civilization when everyone believes they have a shot at a meaningful life. When reality is a post-industrial wasteland, and the dream world offers the world’s most immersive video game, who would want to leave the prison of the dream world?

The Double-Edged Sword

It’s a truism in history-of-technology circles that inventions are morally neutral—the gun that can shoot up a school or hold up a 7-11 can also stop a criminal or turn back an invader. The car that enables your will to travel can also kill you and pollute the atmosphere. Like everything else in life, technology has trade-offs, even dating back to that first mythical bone-club in the hands of the 2001 ape: the femur that kills the tapir and feeds your tribe also gives you the power to murder your brother.

Moralists, on the other hand, tend to view inventions as evil per se if they find its dominant use is destructive or uncongenial. Over the past hundred-and-fifty years, arguments have been made that such evil intrinsically dwells in the movies, photography, cars, guns, the Internet, smart phones, television, radio, nuclear technology, genetic modification, and brassieres.

The problem with such arguments (even when they have merit regarding a particular use of the technology in question) is that the prevailing use of a technology is not inherent in the technology itself; it is, instead, an outgrowth of the culture and market in which that technology emerges, and the personalities that drive it.

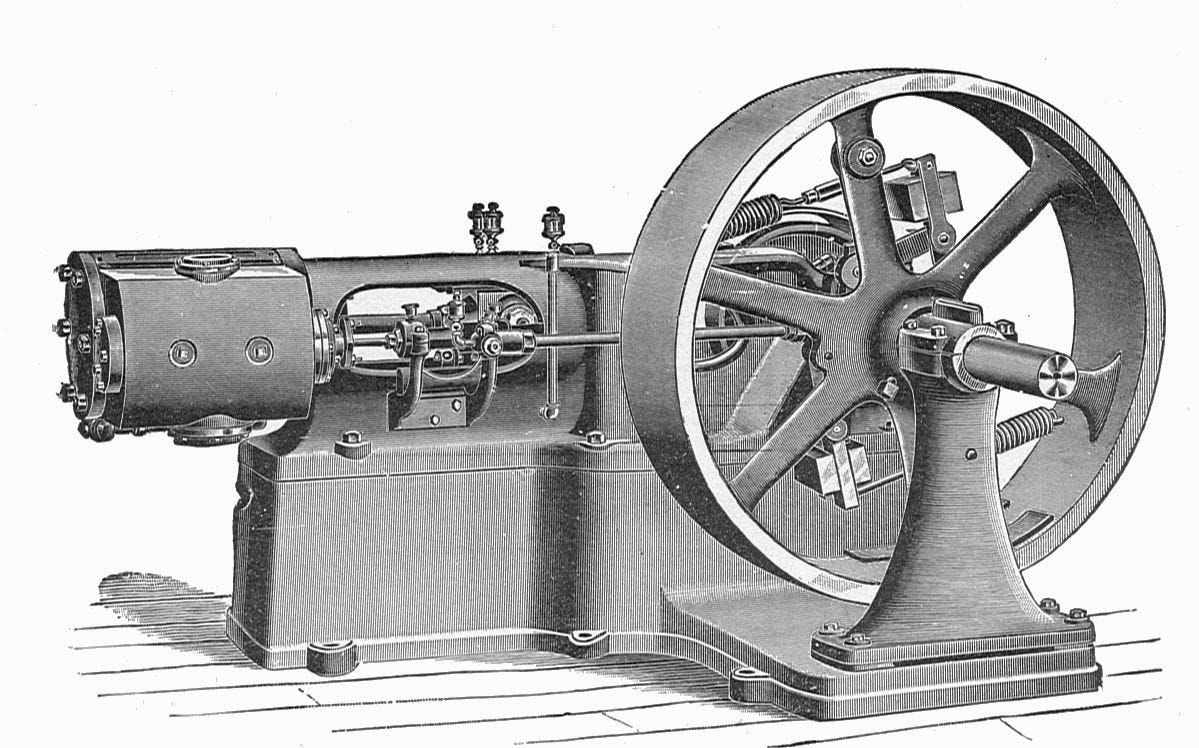

Consider the strange history of the steam engine.

When introduced in Britain, the steam engine revolutionized everything, practically overnight (on an historical timescale). It did this partly because Britain didn’t have as many fast-flowing mountain rivers as its continental competitors, so it couldn’t run as many water-powered mills and factories. This left the island nation at a stark economic and geopolitical disadvantage.

The steam engine changed all that, and it was enabled by the country’s rapidly-developing system of private property rights which provided an excellent incentive for entrepreneurs looking to build fortunes.

And, of course, it didn’t hurt that Britain is an island sitting atop astonishing primordial coal deposits.

That same steam engine, when introduced in the far-flung corners of the British Empire, did not have the same effect. Its adoption was relatively slow for reasons cultural, economic, and political. In places where labor was cheap (slaves, serfs, etc.) there wasn’t as much of an obvious advantage to sinking a fortune into a steam engine, especially when replacement parts had to be ordered from overseas in the age of sail. Local expertise had to catch up to the new tech before the client countries could industrialize, to the extent that their local culture could tolerate industrialization.

Britain, of course, wasn’t the first country to have the power of the steam engine in its grasp. That honor goes to ancient Rome, where both the steam engine and the railroad were built1…and then not disseminated, for the same reasons that the steam engine took much longer to catch on in some of Britain’s colonies than it did in Britain itself.

The uses to which the steam engine was put also varied from location to location, and it took the imperial work of the United States to drag the “developing world” into the “modern world” kicking and screaming, for the fairly straightforward reason that industrial technology necessitates the rise of social institutions that aren’t easily tolerated by cultures where the clan or caste is the basic social unit.

Technology—even your favorite pet-hate technology—is morally neutral…unless your moral paradigm resembles that shown in The Matrix.

Stamps of a Lowly Origin

Am I a dog, that you come at me with sticks?

—Goliath, I Samuel 17:43

Every time I delve into ancient (or, even, not-so-ancient) literature, a strange linguistic quirk jumps out at me:

The worst insults are not the kinds of insults we have today. Today, hurling an ethnic slur, or imputing something weird about a person’s sexual status (bitch, slut, cunt, faggot, motherfucker, etc.) is considered the height of aggression. These insults are aggressive in today’s world because they draw attention to the extent to which the insulted party does not belong in the moral and/or cultural universe of the invector.

But not so long ago, the vilest insults were those that likened the insulted party to an animal in a contemptible fashion. Pig, dog, bitch, rat, snake—these are pretty mild fare now, but they were once so severe that they could provoke duels, lawsuits, and fines in English speaking countries.2 These slurs implied that the insulted party was not even human. This is an old saw with humans who, having lived in close contact with animals for most of their history, have spent a great deal of energy distancing themselves from the awareness of how closely they resemble other animals.

Throughout history, a non-trivial use of technology and the wealth it brings—including many of the uses that we find “comforting”—has been to erect screens to conceal our animal natures. We call this impulse “human dignity,” and it is a basic emotional rationale driving purity codes (whether legal, religious, or customary) surrounding excretion, nudity, butchering, food, and the relationships between humans and animals.

“I write of the great, eternal truths that bind together all mankind. The whole world over, we eat, we shit, we fuck, we kill, and we die.”

—The Marquis de Sade, as portrayed in Doug Wright’s Quills, 1999

So too, does our technological life allow us to distance ourselves from the messy business of being animals. From our toilets (which literally lets us pretend our shit doesn’t stink), to air conditioning (which protects us from weather-related physical discomfort), to prepared foods (which saves us from gardening, slaughtering, and cooking), to having our own bedrooms (which allows us to pretend that our parents don’t fuck and our children/siblings don’t masturbate), to online commerce (which protects us from interacting with clerks and store managers), to online relationships (which shield us from the messiness of body language and lets us distance ourselves from hurt feelings and some of the more complicated aspects of building trust), our luxuries allow us to pretend to ourselves that we are less animal than we really are.

These technologies protect us not just from the realities themselves, but—and this is a vital aspect for a social species—from the awareness that other people know these things about us.

All of these luxuries, great and small, are desirable on their their own merits.

But they come at a price.

The Biological Sensor Net

Since I seem to be talking about science fiction films today, consider the starship Enterprise. It flies through the universe, seeking out new life and new civilizations, and, most remarkably, not crashing.

It boldly goes. Sure, it’s boldly going where none have gone before, but the fact that it doesn’t boldly go straight into every star, black hole, rogue planet, and asteroid cluster as it warps around the galaxy suggests that it has a pretty good idea of where it is, what’s around it, and what it’s pointing at.

This fairly straightforward deduction is supported any time Spock, or Worf and/or Yar, or O’Brien and/or Kira (or one of the characters from those other series that I don’t give a damn about) says “Sensors indicated X is happening in Y manner!”

Without sensors, the Enterprise and her sister ships would be dead in space.

And it’s not alone.

Whales have been having a hell of a time recently. They use sound to communicate and to aid their navigation, and have extraordinarily sensitive ears. Sound travels much better in water than on land, which is why submarines can navigate and detect each other using a combination of sonar (i.e. echolocation) and passive listening. Motorized sea travel in the age of international trade has, by all accounts, been a disaster for the health and sanity of certain whale species.

Without their ability to make sense of the sounds in the water, whales (or some portion of whales) don’t cope well.3

Humans, too, have been known to enter depression, slip into insanity, or kill themselves when their sensory inputs are disrupted in certain ways. While sensory deprivation tanks are a legal way to induce altered states of consciousness, the protracted, systematic deprivation of sensory input (the White Room method and, in a less severe form, Solitary Confinement) and incessant sensory overload (a.k.a. Bombardment) are effective and devastating forms of torture that can unmake a person to the extent that they can never recover, regardless of the care they receive afterwards.

Each technological comfort quietly attenuates (or blocks) one of our sensory connections to the world outside our skin—and some of the more radical ones (including, but not limited to, painkillers and VR) does the same thing to our connection with our skin. Pile enough of these atop one another, and we have the whale’s problem.

Our nervous systems require input within a certain range in order to continue functioning.

Or they cease to function.

But this dependence-upon-signal isn’t limited to creatures with nervous systems.

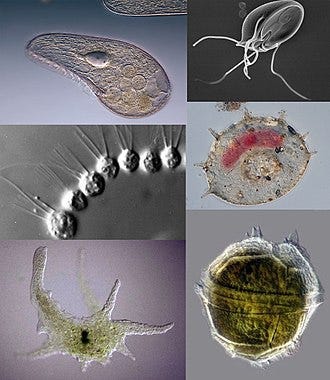

Consider the protozoans. This clade of single-celled critters are (mostly) too little to see without a microscope , and way too small for complicated gadgets like nervous systems. Yet they have, for billions of years, made their way through the world doing the same thing all other life forms do:

Moving, seeking food, digesting and excreting and reproducing, and acting with purpose in service of these imperatives (which drive all life).

And, if you pollute their environment in the right way, you can prevent them from doing these things.

In other words, these creatures are able to live because they have the capacity to react to the signals they receive from the world around them.

This, in turn, implies that they have the ability to receive those signals and understand them.

Of course, saying that is almost the same as saying they’re alive.

Now consider:

Animals are not the only creatures that do this.

The Living World

Living things build systems:

Relationships

Families

Communities

Companies

Economies

Nations

Civilizations

Ecosystems

And each of these systems has one thing in common:

They are also living things.

The ancients had a notion they called “The Great Chain of Being” whereby they ranked each object in the universe, from rocks to gods, in a hierarchy of importance/greatness/goodness/etc. (criteria varied from philosopher to philosopher). If we are to envision living things in this kind of framework in a structural (not moral) sense, we might see a cell as the lowest level of fully living thing, and a group of cells coordinating for advantage as the next level, and so on up to a hypothetical galactic civilization. In this version of the Great Chain, the levels connote merely what is embedded in what, not what has moral priority.

So, back to living things.

All of the living things on this list are alive, even though they’re not made of meat, because they are composed of organs and they behave as all living things do:

They metabolize, react to stimulus, reproduce, defend their own existence, and move through the world.

They do these things without design or direction, because they—like all animals including those little protozoans—are composed of smaller things that all have their own nature in accordance with which they act. The interdependent behavior of these organs gives an emergent character to the behavior of the organism to which they belong.

Each one of your cells functions a lot like a protozoa, but it exists in a web of other systems that allow it to have a specialized function.

And some organisms—like you—are composed both of self-generated organs, and by colonists that make it possible for those organisms to function. You are only able to digest food because your gastrointestinal tract is populated with so many bacteria that they rival, in number, your native cells.4

All the above higher order living things, too, are organisms. The individuals in a nation are less like cogs in a machine than they are like denizens of a forest ecosystem, or cells in a body. Each seeks its own end, and in doing so it sends signals that allow it to co-ordinate with other cells (and larger structures) to get what it needs, and receive signals that tell it what other living things need. Responding to those signals helps the organism aim itself in a productive direction.

For any organism—from a protozoans up through a galaxy-spanning civilization—to function it requires two things:

1) Orientation

and

2) Directionality

In other words:

It must be able to locate itself in the world (in at least a very local sense), and it must know where it’s going.

Any organism that loses directionality becomes dangerous to other organism on its own level (and sometimes organisms on the organizational level below and above itself). Cancer, for example, grows and lives for no particular reason and in dialogue with nothing. In so doing it wreaks havoc on other organs and their support systems, and eventually will destroy the larger organism it depends upon.

Worse than losing directionality is losing orientation—the ability to receive signals, make sense of them, and react to them. This loss also costs an organism directionality, rendering it truly, deeply insane. An organism bereft of orientation remains insane until it recovers its orientation...or dies.

Unraveling

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Those words don’t describe our world today. They sprouted from the late 19th century pen of William Butler Yeats, an English mystic and poet wrestling with his growing conviction that European civilization was about to collapse.

Civilizational collapse is like dying from old age—it’s agonizing, it takes a lot of time, and if you’re caught in a collapse you spend most of your time just getting on with things and enjoying whatever time is left.

But that doesn’t mean that, if your nose is tuned in to the right signals, you can’t smell it when it’s happening. Over the five decades following Yeats, European civilization did collapse.

Literature—from ancient times to the present—is replete with characters who smell impending doom and try to warn others about it, only to be castigated as anything from “insane” to “treasonous” to “satanic.”

In The Iliad, Cassandra is a princess of Troy cursed with prophecy. She knows the doom coming for her city and attempts to warn her father, but he (and the rest of her family) will not listen, judging her insane. She is but the first of a longstanding literary type, a type which persists because Cassandras exist in real life.

A handful of Cassandras have emerged preceding each of the recent disasters of the 21st century. I’m sure you can think of a few. They have been savaged so dependably and so thoroughly that there is now a heuristic floating around in the dissident intellectual space:

“The only thing less forgivable than being wrong is being right too early.”

Cassandras don’t do well, either in literature or in real life, because humans have a hard-to-shake intuition that to predict something is to cause it. It’s an intuition to a form of word-magic called “prophecy” (in pop mysticism today, it’s referred to as “manifesting”). I’ve discussed the recent surge in this type of magical thinking and practice (as well as other sorts) at some length in my article A Time of Magic.

But back to the main topic:

If you read the surviving literature preceding any major civilizational shift, you will feel the sense of foreboding creeping into it around two generations before the shit really starts hitting the fan. We can smell the change in the air.

The question is...

...what are the Cassandras whiffing on the breeze?

Forbidden Knowledge

Hard time make strong men. Strong men make good times. Good times make weak men. Weak men make hard times.

—G. Michael Hopf

The above bit of “ancient wisdom” has been making its rounds on the Internet for the last few years, but ancient it isn’t. It comes from Those Who Remain, a 2016 novel by post-apocalyptic fabulist G. Michael Hopf.5

Aphorisms, old or new, catch on because they crystallize something inchoate in the popular consciousness. Hopf’s formulation effectively articulates the broadly-shared intuition that we’re on the back-side of utopia and sliding inexorably down into the abyss. It does this by pulling forbidden knowledge out of the back drawer of historiography.

Forbidden knowledge?

Well, yes. Because, contrary to what you heard, the United States and the Allies didn’t win World War 2.

Georg Wilhelm Frederich Hegel did.

Throughout the 19th century, the intelligentsia began to believe that the world would be better if they controlled it, rather than merely studying it. Taking their cues from the power and wealth accrued by those who applied their engineering savvy to human subjects (i.e. factory owners and managers), the intellectual leaders of the world—from England to America to Germany to Moscow—abandoned the tension that defined the post-enlightenment west between liberal individualism6 and traditionalism,7 and instead tooled up a new version of Plato’s ideal political system, whereby the philosopher-kings would rule a benevolent State in the interest of Progress (with a capital “P”).

They premised their takeover on Hegel’s view of history, which holds that the universe works out its chaos through setting contradictory things against one another and letting them battle it out. In the end, both lose out to a synthesis of the two, which then must do battle with the next antithesis,8 and so the spiral of history progresses onwards and upwards until, at the end of history, all contradictions will be synthesized (through the political process) into a glorious end state where all consciousness is aligned and everything is understandable. In the process, consciousness itself spirals upwards from the primordial soup through the individual, to the ethnicity, and then to the State, and then the Superstate, and eventually manifests the self-consciousness of the universe.9

If you’re a science fiction fan (or a fan of Carl Sagan) you will have heard a version of this view of things before:

“We are the universe made manifest, trying to figure itself out.”

—J. Michael Straczynski, Babylon 5

For our purposes, the upshot of the victory of the Progressive view of history is that it murdered the nascent historical sciences.

Before the end of World War 2, scholars like Toynbee, Durant, Spengler, and others were starting to converge on a Grand Unified Theory of history based on the surviving evidence, and they were all converging on a view that has since been broadly categorized as the “cyclical” view of history. Rather than holding that history moves in circles, it sees the rise and fall of civilizations, the frequency and nature of wars, the health and wealth of nations, and the triumph and diminishing of religions as each moving like a stack of waves through an oscilloscope.

Although no two civilizational waves are identical, they do share a structure. Each has a start, a rise, a peak, a fall, and a denouement (rather like a story).

On this view, each point in this cycle is marked by certain characteristics.

A young and confident civilization will value courage, growth, magnanimity, cruelty, and other aristocratic virtues (also known as “master morality”).

A civilization at its peak will turn its focus towards charity, justice, and leveling the playing field.

A civilization in decline will turn its focus inwards on protectionism, micromanagement, petty grudge-matches, and the like.

This view clashes with the Progressive view of history on several points, so much so that twenty years ago invoking “historical cycles” was likely to get you laughed out of respectable intellectual company, if it didn’t get you branded a fascist reactionary.10

“History does not repeat itself. But it rhymes.”

—Mark Twain

Despite the cyclical view’s heretical deviation from Progressive orthodoxy, it accords better with the facts as we have access to them. Civilizations not only appear to move in cycles, they’ve now been shown to move in cycles by a new generation of dissident quantitative historiographers exemplified by Peter Turchin. Turchin uses math (thus, “quantitative”) and predictive modeling to argue that he’s nailed the root cause of historical cycles. Characters like Strauss and Howe have likewise attacked the problem from a non-quantitative angle,11 and, despite weaknesses in their general theoretical model, have persuasively documented this kind of rise/decline rhythm as happening on a more-or-less four-generation cycle.

So, despite progressive dogma, the deep intuition that history tends to move in cycles seems to have something to it. It is this heresy that the “strong men create good times” aphorism taps into, and the reason that it has become popular wisdom.

But even if we are to grant that it is basically true, the question persists:

Why?

Specifically, why should “good times create weak men?”

I expect that you, like me, have known people who have been able to make significant gains because they had greater resources to call on. For every few spoiled brats in the world, there’s a diligent heir or heiress that kicks serious ass. For every few Vanderbilt-style families that squander their fortunes after a generation or three, there’s a Ford family, or a Rothschild family, that manages to build a genuine and lasting dynasty that endures for much longer than one might expect.

Benjamin Franklin came from such a family—the Folger family12—and that dynasty (and family name) continue to be important today. Charles Darwin came from such a family. John Adams founded such a dynasty.

So why in the hell should good times create weak men, instead of providing seed capital for further greatness?

Wealth and Change

“The world is changed. I see it in the water. I feel it in the earth. I smell it in the air.”—Treebeard in Return of the King by J.R.R. Tolkien

Poverty is the default historic condition of humanity. Violence, abuse, and squalor are shot all through our history. They show up in art from the neolithic period forward.

Misery is common the world over, and shows up alongside that other stuff in ancient humanity’s surviving art.

But depression…doesn’t. Not until later. Not until decadence sets in.

Not until real wealth comes into play.

It’s a puzzling phenomenon, which I saw reflected in my own experience growing up missing-meals poor, but with social access to the world of the wealthy.13 The poor people around me were brash, uncouth, often abusive, sometimes nasty, but they were also surprisingly…well, “happy” isn’t the word for it, because there was a lot of misery. But where they were hurting, they were actively hurting. There wasn’t a lot of ennui floating around in that pool.

By contrast, the wealthy people I knew seemed to fall into two camps:

Those who really knew how to live, and those who could barely bear the pain of existence. The vital on one hand, and the depressed on the other.

And as I climbed the social ladder through my life, I consistently found less misery, but more depression, more ennui, and more dissociation.

It looked almost as if material wealth caused depression…except, I knew from my own experience (as a poor kid who battled crippling depression for several years) that it couldn’t be just about material wealth.

And besides, if riches caused depression, what about those vital wealthy people who really know how to live even when they are hurting and lost? I’ve known more than my share. The art of the ages shows this, like the Cassandra, as a reliable literary type—because, like the Cassandra, it’s based in reality.

Something else is going on. Something about wealth provides an expanded opportunity for depression to take hold. Something about it allows the pain of being abused, jerked around, trapped, and frustrated to turn into a white noise of disorientation instead of occasioning anger, determination, or revenge. And whatever it is, it isn’t simply learned helplessness—learned helplessness often co-occurs with depression, but it is its own animal with a different set of associated difficulties.

Coincident with the greater tendency towards ennui that comes with wealth, we find that people who have the means tend to overindulgence in trivial pleasures. The result is an out-of-balance life, consumed with the novelties-of-the-moment whether they come in the form of drugs, alcohol, video games, consumerism, politics, or moral panic (or other social fashions).14

Is this tendency towards trivialities (i.e. hedonism) causing the ennui? This seems a straightforward deduction, but if it is true, it doesn’t actually tell us anything important because it leaves unanswered the more basic question:

Why do wealthy people get obsessed with such trivialities?

Traditional Political Medicine

When the whiff of civilizational decay appears on the wind, the usual suspects appear on the scene to revive and heal the patient.

If you’re of a conservative bent, you’re going to think that a return to the good old days, to tried-and-true moral paradigms, to old-fashioned values, and to the ways of our ancestors will re-inject strength into an ailing civilization. A religious revival, a Napoleon or Caesar who can inspire virtue, or a sudden emergency that forces people to start paying attention to God, Country, Family, and Character are what’s in order. Strong men make good times, so let’s inject some hard-core discipline into the culture and make strong men again before we get to the nadir of the hard times made by the weak men.

If you’re of a leftish bent, you’re going to see the vast inequality in wealth, power, and prestige that happens after the crest of the curve as the cause of the civilizational malaise, because it saps the motivation of people to do well and lets the “haves” lord it over the “have nots.” Such times call for a leveling event, like a revolution or a plague or a visionary leader with an aggressive legislative agenda,15 to lift our eyes to the future, unburdened by what has come before, and redistribute wealth and opportunity by force in order to set the table for the next golden age.

Either the conservative and the left-ish reactions to decay might be appropriate if they correctly apprehend the cause of the decay. Unfortunately, each view assumes the conclusion without appeal to the evidence—either reaction would be inappropriate (or counterproductive) if it were to turn out, for example, that both parties are somehow right.

Or, worse, that both parties are entirely wrong.

If inequality, hedonism, depression, and disorder are the effects of the forces pushing a system towards collapse, then the conservatives are advocating treating a brain tumor-induced headache with exercise and massage, unaware that their distractions could keep the patient from getting surgery before it’s too late. Meanwhile, in such a situation, those of a leftish bent are pining for palliative care—rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic to make life as bearable as possible until we all sink into the depths.

Something is going on here. It’s something that the Cassandras can smell well before the rubber meets the road. It’s something that wealth accelerates, but does not necessitate. It’s something that affects individuals as well as civilizations, and drives both to suicide.

And it’s something to do with that ape that understood that a bone could be a club, and that VR addict plugged into the Matrix, and the remarkably crash-free trek record of the USS Enterprise.

And Peter Turchin managed to get his hands on a piece of it.

At the risk of oversimplifying by condensing a man’s entire body of work into a paragraph, Peter Turchin’s model of civilizational collapse looks like this:

Poor people have an incentive to create and accumulate wealth so that their children can have better lives. As generations go by and the wealth in a civilization increases, more people have the opportunity to put their children in a position to climb the social ladder. As more people begin to train for jobs in prestigious fields, there comes a point where there are more aspirants to prestige than the system can absorb. These surplus wannabe elites feel entitled and disgruntled and really need a job, and they form a counter-elite class intent on conquering the system and bending it to their will, or burning it down to build it anew. Eventually, there are too many surplus elites for the system to resist, and they tip over the apple cart.

Turchin calls the phenomenon “elite overproduction,” and he can show that every civilizational collapse—major or minor—for which he can recover or reconstruct records is precipitated by surplus elites swooping in and seizing power. From Caesar to Lenin, from Robespierre to Napoleon, from Jefferson to Cromwell to the War of the Roses, sic semper est,16 QED.17

I said Turchin only had a piece of it—how can I say that if his case is so airtight?

Because his case does not account for the disorder, the dissolution, the depression, the lack of power-efficacy of the incumbent ruling class, and the social decay that characterizes the run-up to civilizational turn-overs.

But what if there’s something that does, and it’s something of which Turchin’s model is an epitome?

But it Rhymes

As a young novelist, I was treated during a bull-session to an impromptu lecture by a publishing business historian about how to keep oneself from going bankrupt from success.

Yes, you read that right.

Because of their long-term supply contracts and the capital flows required to maintain them, publishing companies are often put at greater financial risk by a runaway success than they are by a string of moderate failures. Though I have not been able to locate it for this article, the impromptu lecturer produced a write-up of Scholastic Publishing’s near-collapse due to difficulty securing credit to buy the supplies to fulfill demand for one of the early Harry Potter books. The difficulty prompted Scholastic to make changes to its business plan that saved it from dissolution.

Too much of anything, even success, can be poisonous.

If you zoom in on Turchin’s model of revolution, past its supporting evidence to its central core, a strange dynamic plays out:

Success, by definition, yields disproportionate wealth. Scatter a couple pounds of wheat in a garden, and with luck you’ll reap twenty or thirty pounds at the end of the season. Novelist David Brin has long held that the great achievement of the modern west was transforming the pyramidal society of feudalism (where people are mostly poor, and there are fewer members of each class rising to a singular ruler and his coterie at the top) into a “diamond society” in which the extremely poor are relatively few, the middle class is big, and the rulers are once again relatively scarce.

Turchin’s model suggests that when a ruling class does well enough that the peasants can aspire to become courtiers, then Kings—in order to hold on to power—must invent make-work for the striving children of those peasants. This diamond shaped society then gives way to protectionism, because the Kings can’t invent enough useless jobs for the strivers to fill, resulting in aspirants who have no place, and who then overthrow the system.

Although Turchin doesn’t give it as much attention (in the books of his that I’ve read), the flip side of this dynamic is that the in-power elite also grow insular as they attempt to protect their power from the rising wannabe-courtiers nibbling into their territory from the outside.

To the extent that elites insulate themselves for protection, they create a separate reality which, over time, naturally grows more and more impervious to the outside world. They can circulate amongst themselves and have a fantastic time imagining and planning a new world at Aspen, TED, Davos, G7, and other such conferences, navigating a fantastically curated (and promising-looking) reality which, despite the massive sums they spend on data analytics, diminishes in resemblance to the real world over time.

Imagine that Spock started editing his analysis in order to bolster Kirk’s morale and fortitude, and you get an idea of what happens. Without fortitude, Kirk is a useless captain, and the Enterprise has no sense-making apparatus. Lying a bit to keep the fortitude up seems like a pretty good call.

But if Spock did this long enough, the lies would grow, and Kirk would wind up captaining the ship from a dream world.

However, let’s not sit too easily in judgment of our purported betters. It’s happening to all of us.

You have the world at your fingertips—you’ve got a phone in your hands or a computer in front of your face as you read this—with astonishing access to almost anything you could ever want to know. Sure, 90% of what you find online is useless bullshit, most of it probably isn’t even generated by humans, but if you have a question to answer, and you know how to dig, you can find what you want.

And yet, the generations who have, since birth, never known a world where this wasn’t true seems less able to learn, understand, and do for themselves than ever before.

As we can get what we want easily, as we can see what we want and block or ignore what we don’t, we can build ourselves worlds that show us the reality we expect—which, even if it is an unpleasant reality, is always to be preferred from the unexpected for good solid survival-based reasons:

If you can be confident that what you expect and what will happen are substantially the same, you can plan for the future. If you don’t know what to expect, you experience dread, terror, cognitive dissonance, fear, and other forms of distress. Anything that can prevent that distress—such as living in a dream world built to match your expectations in a bearable fashion—is one you’ll gravitate to.

And so, just like our ruling class, we slip into cognitive “echo chambers” that don’t necessarily validate our desires, but they do validate our expectations.

As above, so below.

And in this we find an echo of everything else we’ve touched on so far:

Social decay

Rat Utopias

Depression and other mental illnesses

Generational wealth erasure

Civilizational Collapse

The pattern doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.

All Living Things

The rats in the rat utopia quit breeding and socializing long before their colonies reached their carrying capacity.18 They didn’t starve; they gave up.

The Vanderbilts lost their fortune while the Fords are still going strong.

Wealthy people are prone to ennui.

The Romans, the English, the Europeans, the various Chinese ruling classes, the Greeks, the Persians, the Egyptians, and the Babylonians all lost their way and fell quickly from the peak of their glory.

The developed world is cracking at the edges and its elite are too out of touch to do anything about it.

Yeats smelled the crash of European civilization two generations in advance.

Neo, in the end, kept The Matrix alive.

And all of these things happened—or are happening—for the same reason.

When a person loses an arm, they don’t simply not have an arm. They often continue to feel the presence of the arm that’s been excised. Their brain expects signals from the nerves in that arm, and, in an attempt to make sense of the world, it invents them when it doesn’t receive them. It can invent crippling amounts of pain, which can only be alleviated through using optical illusion to fool the brain into thinking that the arm is there, and that a live feedback loop exists between the brain and the arm.

Absent expected signaling, the brain, in a small way, goes insane.

When people sustain hearing damage, they don’t simply stop hearing in the damaged frequency range. They get terrible tinnitus (ringing in the ears)—a hallucinatory sound generated by the nervous system to fill the holes in their auditory spectrum.

When the rats in a rat utopia don’t have to cooperate and play and have relationships to survive, they don’t. Because all their material needs are met, there is no discernible purpose to the behaviors that keep them socially healthy. Their behavior makes no difference in their access to food. The rats have no signal from their survival circuit, so they fill the need for signal with noise: gang violence, obsessive self-grooming, bullying, and depression.

When elites become insular, they do not receive the signals from their subjects. Even if one assumes the best of intentions and no corruption at all, there’s no way an insular elite can govern effectively when surrounded by ramparts of bureaucracy which, at every level, filters the information it passes up the chain for its own reasons.

And when you don’t need to hunt, grow, and cook your own food; when you don’t need to read or have conversations or contemplate complex tales in order to have the satisfaction of encountering deep thought; when you don’t need to tell jokes and risk embarrassment in order to laugh; when you don’t have to play an instrument or sing to enjoy music; when you don’t build your own tools; when you don’t need to touch another human or maintain a relationship to slake your sex drive; when you don’t have to build a house to have shelter; when you don’t have to feel the swings in weather that make your bones shiver and ache; when you don’t have to share space with another human in order to belong somewhere; when you can hide your fantasies and ugly realities from yourself by concealing them from people you have to look in the eye; when you don’t have to shovel snow or fix machines or solve problems on-the-fly because something better, cheaper, and more socially respectable can be bought off-the-shelf; when you can pretend your shit doesn’t stink…

…well, any one of these things by itself is an upgrade in the quality of life, but each one cuts you off from a signal path. All of them together leave you blind, deaf, and bereft of touch.

Without orientation and directionality, living things go insane and flail about in search of anything that can help them make sense of the world. Humans slip into depression and hedonism, businesses start making boneheaded decisions, governments slide into hapless tyranny. A civilization so afflicted in its signal-receiving capability—whether due to too much difficulty, too much luxury, or too much change too fast—begins to buck and flap and flail about like a screaming man freshly blinded by branding irons.

The Cassandras can hear the screams and wave their arms to draw attention, but their cries go unheeded because the rest of the crowd has lost their ability to receive signals, having already cut off their own antennae. In this way, the Cassandras can be thought of not so much as geniuses out of time, but as the last holdouts who have not yet lost their ability to smell the approaching fire in a world where the best have no confidence, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned.

Unabomber Ted Kaczynski argued in his manifesto Industrial Society and its Future that technology has its own logic, and that logic necessitates oppression as humanity is subsumed by the machine.

He wrote that manifesto on a typewriter, on paper produced in paper mills, and it was published in the New York Times. For all his monstrous means, for all his brilliant insight, the fact of his publication proves this particular part of his thesis wrong. However deranged from the abuse he suffered at the hands of the system, Kaczynski was an ape with a bone-club. He knew where he was, and what he wanted. He had orientation and directionality.

Ted, and Hitler, and Stalin, and Napoleon, and Caesar, and Pol Pot, and other such monsters arise in worlds where most people have neither orientation nor directionality. They are, each one, products of a civilizational end-state, where the signalling regime is so polluted that reality is vanishingly distant. Their power came from the fact that they each correctly apprehended some aspect of reality in a way that was alien to those around them.

So too with occultists like Newton, Parsons, Einstein, and Washington; or industrialists like Musk, Bezos, Thiel, Rockefeller, Ford, and Carnegie. They read the room. They opened their eyes. They were willing to accept the signals they received—even when they weren’t ones they liked.

Living systems cannot properly function without knowing where they are (orientation) and where they’re aiming (directionality). They cannot operate without signal. Without signal, they flail about for anything to replace it, and they will accept anything that seems to work—booze, drugs, cults, bad relationships, isolation, machinations, or revelations.

When a wealthy patriarch dies, the family fortune goes into disarray without his guiding vision, unless he’s found a way to pass the vision on along with the money. This is why the Fords continue to rule, while the Vanderbilts do not.

Without signal, there is no awareness.

Without awareness, there can be no movement, and no vision.

The Matrix prevails. The mind caves in. The civilization falls.

Until a new, more curious ape takes up the next club and uses it to bash down the heavens.

The full history is even wilder. The steam engine was dreamt up by Archytas in 400 BC. Hero and Vitruvius both revived his idea in the Roman era, and that’s where it got the most pre-Enlightenment traction—which is, to say, not a lot. It was used as the basis for organs in medieval churches, and a steam turbine engine was invented in Ottoman Egypt in the 16th century. The English were pulling on very ancient threads when they used it to transform their little island into an industrial powerhouse.

This is to say nothing of countries in Europe—some of which, according to one of my professors, had such laws regarding such insults on the books as late as the 1980s—let alone the rest of the world.

This fact is behind the controversy over offshore wind projects on the East Coast, though evidence implicating the projects in right whale beachings seems to be thin at the time of this writing.

Their weight, however, is relatively small, totaling only a pound or two for a 150lb adult.

I haven’t read the novel myself, so I can neither recommend it nor warn you off about it.

Embodied in property rights, the individual right to violence, freedom of speech, freedom of association, and freedom of conscience.

Embodied in hierarchy, localism, religious solidarity, and ethnic solidarity.

An Hegelian view of the last two hundred years in Europe would look roughly like this: Traditionalism battles Liberalism, and Liberal Traditionalism wins, which then battles Robber Barron Capitalism, leaving Managed Capitalism, which then battles Marxism, leaving a Third Way (a.k.a. state fascism or “social democracy”), which then battles Corporatism, leaving Corporate Fascism, and so on.

Yeah, this is some woo-woo esoteric shit and you may have an understandable an impulse to dismiss it on those grounds if you don’t like it for other reasons. The problem is, both traditionalism and liberal individualism are also built atop mountains of magical thinking and occultism. Whether you like it or not, all human traditions are dealing from the same superstitious card deck—in my view, this means you gotta evaluate these things on their own merits rather than pre-judging them by where they come from. I don’t buy Hegel’s historical view on its own merits. I discuss some of my reasons in passing in a number of articles, which you can find indexed here and here.

Which is ironic, given that fascism is a distinctly Progressive political philosophy, but I digress.

Strauss is a lawyer and a theater nerd, Howe is a political consultant with an interest in psychology.

Yes, like the coffee.

Note: by “wealthy” I mean “People who don’t worry about where the next meal is coming from and who can afford some nice toys.” Anyone from middle class to generational aristocracy qualifies.

Some among you will, I know, default to assigning this spiritual malaise to demonic influence and/or divine reprobation brought on, in either case, by a lack of religious faith. That position is hard to accept once one notices that the religious self-help literature corpus and therapy industry are just as robust and profitable as are the secular markets in these areas, and the market for psychopharmacutical mood stabilizers also does pretty well among the religious. So unless Satan is alive and well and living in the Christian church, I humbly submit that can safely conclude that he and his putative minions aren’t the primary culprit here.

For more on the affection for, and impact of, leveling events, see Thomas Picketty’s Capital in the 21st Century and Walter Scheidel's reply The Great Leveler. Both are bracing reads.

Thus it always is.

Quod erat demonstrandum. or “Thus it is proved.”

For a fuller discussion of the rat utopia experiments, see St. John and the Beautiful Ones

Comments

Post a Comment