La France en Feu!

It all began with a curse . . .

King Philippe IV Le Bel (the beautiful) was said by contemporaries to be less a man than a statue, with a face- and heart- of marble. The driving purpose of his life was the centralization of power in France, efficiency, order, and rationalization of law. But achieving this would mean war and wars were (and are) expensive. Squeezing his population would only yield so much before it would become counterproductive and destabilizing. Philippe needed to get creative.

Ladies?

Ripping off the Jews and exiling them was the obvious first step, but Philippe was committed to more comprehensive fiscal reforms to complement his political plans. The Church owned an enormous amount of land in France, the revenues from which were controlled by the pope in Rome. Philippe got into it with Boniface VIII, who in response to their spiraling conflict advanced the then-novel claim that the pope was not only the spiritual leader of the world, but also the held power over all temporal authorities as well. Philippe, as it happened, thought there was a lot of potential in that line of reasoning, so he sent a thug squad to Rome, had them beat up the elderly pope with the help of some of his local enemies (the extent of the violence is disputed), and when Boniface died, secured the election of someone just as assertive in his authority but properly deferential to France. The compliant Benedict XI died in turn about a year later, but the project was going so well that Philippe felt confident in elevating his old friend Raymond Bertrand de Got as Pope Clement V. Clement realized he would face a hostile reception in Rome as the local aristocrats, accustomed to picking the pope, were growing violently tired of the French king’s interference. So he never went there, instead setting up shop in various cities in France, complete with a collection of newly-minted French cardinals, until he finally settled in Avignon. There would not be a pope in Rome again for nearly seventy years.

Clement was not always happy to help Philippe with his schemes, even though he was willing to put Boniface VIII on trial- posthumously- for the crimes of heresy and sodomy. But in the end he always went along with the program. And as it happened, that would now include Philippe’s personal debt-forgiveness plan: the liquidation of the Knights Templar.

The Poor Knights had become fantastically wealthy as administrators of vast estates donated to the cause of crusading despite their no longer doing any real crusading, and had largely moved into the innovative and lucrative new field of banking. They were less a monastic order than a vast, untaxed hedge fund- one wonders that they didn’t open a university. Along with this they had developed what even sober historians like the excellent Desmond Seward called “a mania for secrecy.” Exactly what they were really up to is best left to professional conspiracists, but Philippe, who owed them a ton of money, had a theory: heresy and sodomy, because why not? He browbeat Clement into dissolving the order and confiscated much of their property, but would have let them be pensioned off had the Grand Master of the Order, Jacques de Molay, and some of his closest subordinates not insisted on maintaining that they were not, in fact, heretical sodomites.

On March 18th, 1314, de Molay, Geoffroi de Charney, Preceptor of Normandy, and others were burned at the stake in Paris. All were defiant to the end, with de Molay pronouncing that Dieu sait qui a tort et a péché. Il va bientôt arriver malheur à ceux qui nous ont condamnés à mort" ("God knows who is wrong and has sinned. Soon a calamity will occur to those who have condemned us to death") and legend has it that de Molay prophesized that both the King of France and the Pope of Rome would answer to God for their crimes within the year. Doubt if you like, but there’s no question that things really went downhill for the French monarchy and the western Church from that point forward. Clement V died a month later, and Philippe IV was killed by a stroke while hunting within a year at the age of 46.

That’s why I get my information from Assassin’s Creed.

That wasn’t great for Philippe, but no one at that point would have imagined the kingdom was in any great danger. Philippe IV had three grown sons- Louis, Philippe, and Charles- each married, and no Capetian king in five centuries had ever failed to secure the line with a male heir. Philippe IV also had one surviving daughter, Isabella, married to King Edward II of England. But there were some problems. For one thing, Philippe IV’s daughters-in-law had all been implicated in the Tour de Nesle scandal, where two of the ladies, Margaret, daughter of the Duke of Burgundy, and Blanche, daughter of the Count of Burgundy (there were a lot of Burgundies) decided to cheat on their disagreeable husbands (Louis’ actual nickname was “the Disagreeable,” Le Hutin) with a pair of knights. Joan (also from the County, not Duchy, of Burgundy), Philippe’s wife, didn’t participate but didn’t tell anyone either. That task fell to Isabella- more on her later. The knights went to the stake for lèse-majesté and the ladies would have followed but for the fact that Philippe IV didn’t want to alienate their powerful families. So he just threw them all in prison and waited for the pope to sort it out. But king and pope both died the same year as the scandal, and with no one to press them, the cardinals dithered for two years in the delicate task of choosing a successor.

Cuck Dynasty?

As it happened, the problem was solved for the new King Louis X by Margaret’s somewhat convenient death in the dungeon, and he wasted little time in marrying again, this time to a Hungarian princess. She quickly became pregnant, and his regime looked secure, but then he drank too much chilled wine while playing tennis and died a very French death. His posthumous newborn son Jean only lived a few months. Louis did have a daughter with Margaret, Joan (the women didn’t vary much in the name-pool either), but as her parentage was questionable, as a matter of law it was decided by all involved other than Joan that the Kingdom of France could only be inherited by males through the male line, a principle originating in the Salic Law of the old Franks- more on that later. Joan did end up with the Kingdom of Navarre (now on the border between France and Spain) by way of their not caring about the Salic Law, but the throne of France passed to her uncle Phillipe V. Philippe seems to have been a decent enough sort- of the three brothers he actually liked his wife- and the biggest problem his reign faced was the great Leper Conspiracy of 1321. But he also died without a male heir, and was succeeded by his younger brother as Charles IV.

It actually was a serious problem.

Charles faced a number of problems, most stemming from his following in his father’s footsteps in scheming to centralize power in France. As it happened, his brother-in-law, Edward II of England, was not merely king of that island but also one of Charles’ largest subordinate landowners as Duke of Guyenne. This territory, in the modern Bordeaux and Dordogne region of southwestern France, was a vast and wealthy fiefdom, which Charles wanted under crown control. Taking advantage of Edward’s weak position in England, he confiscated the territory under the pretext that Edward refused to do homage in person, and then after a brief war against the hapless Edward returned it- greatly reduced- under much less favorable terms. His sister Isabella might have objected to this treatment of her husband had she not heartily hated him by this point; Edward preferred the company of his male favorites, once leaving her behind on a Scottish battlefield while he escaped with his boyfriend, to whom he’d previously given her jewelry. They had somehow managed to have a son, whom she convinced her husband she would take to France to do his homage for him. Once there, however, she took up very publicly with one of Edward’s greatest enemies, Roger Mortimer, married off the prince, also Edward, to a Hainaut heiress, invaded England with Mortimer, deposed Edward II, replaced him with his teenaged son- now Edward III- in 1327, and probably had Edward II murdered in a particularly Game-of-Thronesian way. Isabella’s nickname, incidentally, was La Louve (the She-Wolf).

Yes, Edward II is that guy from Braveheart.

Within a year of the coronation of Edward III, Charles was dead, and true to the pattern he left no male heir. This posed a much bigger problem than the deaths of his brothers, because France was now completely out of Capetians. The nearest relative through the male line was the son of Philippe IV’s younger brother, another Philippe, Philippe de Valois. Things seemed stable for a few years, until Edward III came of age in England. He had Mortimer executed, imprisoned his mother, and somewhere along the way it occurred to him that he arguably had a better claim to be the king of France than Philippe VI.

Edward was the direct grandson of Philippe IV and a nephew of the previous king. Philippe VI was descended from Philippe IV’s younger brother and was the second cousin of Charles IV. The problem for Edward was that Salic Law that only recognized claims through the male line. Edward argued that the policy shouldn’t apply, being novel; Philippe countered that it was actually a totally ancient custom. The respective sides decided to settle the issue the fairest way they could think of: one-hundred years of war. Historians labeled the conflict, somewhat unimaginatively, the Hundred-Years War.

On the surface, it should have been an easy victory for France. The kingdom had five times the population of England and was far wealthier. But England had some things going for it as well. Being smaller meant it was more easily centralized, and its finances were better organized. The money was there for a real army and rapacious English aristocrats would fight alongside professional military contractors, including the famed longbowmen. Importantly, they would be fighting in France, where all the damage would be done. And not everyone in France was sold on Philippe, with his traditional Parisian royal desire to impose law and taxation on over-mighty feudal magnates. Perhaps Edward, in distant England, might be better after all…

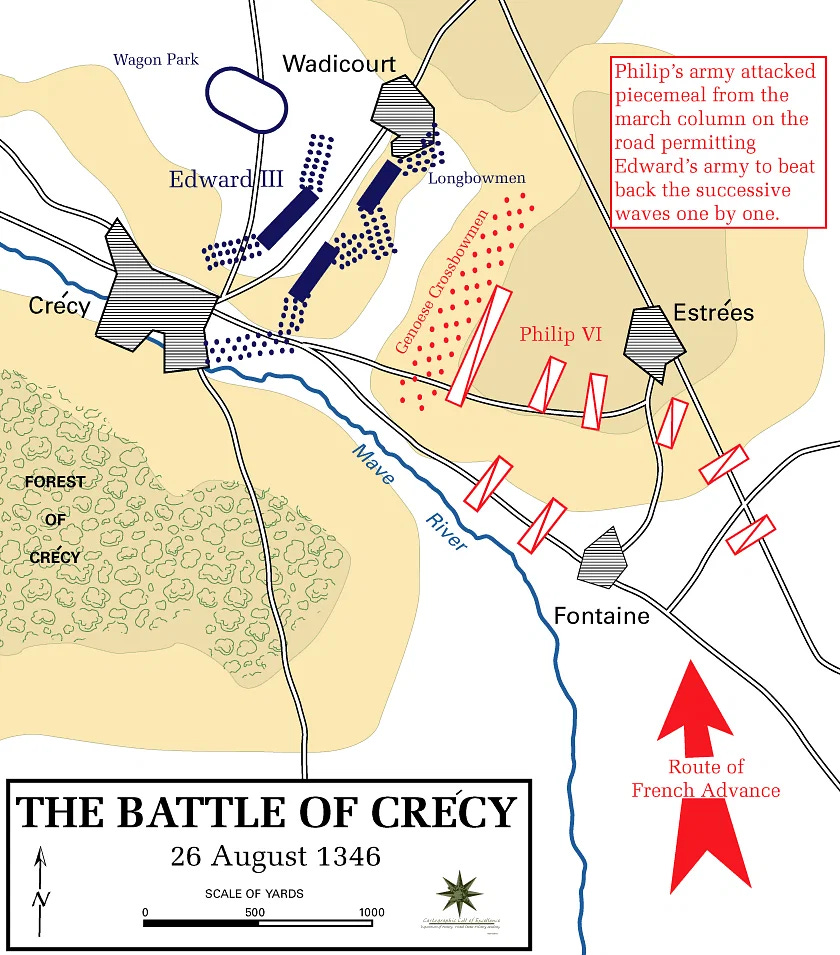

The first phases of the war were a disaster for France. The English invaded through Brittany, burning and pillaging everything in their path, until they arrived at Crécy-en-Ponthieu south of Calais in August of 1346. Philippe sent his brave but incompetent son Jean to repel the invasion, then joined him for the battle with his own force. They outnumbered the English two-to-one, but the latter were dug in on a muddy hillside, perfectly positioned to repel a cavalry charge. The French then launched a cavalry charge, which resulted in the horrific hand-to-hand slaughter of pretty much all the French aristocrats who weren’t killed by arrows or trampled into the mud. Philippe himself took an arrow wound to the face and his ally, King John the Blind of Bohemia, was killed because he was, well, blind. The English took Calais and would hold it as a Northern Gibraltar for two centuries.

Edward wasn’t king of France yet, but he’d wiped out a good percentage of the aristocracy, and made it clear that England was going to be a major factor in French politics for a while. The main impediment to Edward following up with further campaigns was another unfortunate development for France in 1346: the Black Plague (in fairness, this was bad all around). A third of the population of Europe died in the worst epidemic in history, right in the middle of the worst war France had seen since Julius Caesar. By the time anyone was fit to fight seriously again it would be the eldest sons of the previous combatants warring- England’s forces led by Edward III’s designated heir, Edward the Black Prince, and the new King Jean II of France. True to form, Jean fought another poorly-executed battle at Poitier in 1356 that not only got another batch of French nobles slaughtered but also resulted in his own capture and imprisonment in England for most of his reign.

The Black Prince, source: the BBC

France was suffering enormously at this point. The country was overrun with bandits and demobilized soldiers, starvation and disorder were rampant, and with the king a hostage abroad, the remaining nobles did as they pleased. The only person who stood in their way was Jean’s son Charles, who took over after his father died in captivity. Charles V Le Sage (the Wise) was exactly what his country needed at a moment when it needed it the most. True to his name, Charles developed farsighted policies and recruited talented servants from all walks of life, including a hideous Breton knight named Bertran du Guesclin, a masterful strategist and deadly combatant whom Charles made Constable of France. Between the two, they hatched a plan to draw the Black Prince into an unwinnable proxy war in Spain into which they sent all the troublesome surplus soldiers that were terrorizing the countryside. The Black Prince died of dysentery and with Edward III now in his dotage, France seemed secure for a while

It was not to be. Charles was wise but not healthy, and he died at 42 in 1380. He did have a son, and with the reputation of the father being at an apogee, his prince, now King Charles VI at the ripe age of 11, was nicknamed Bien-Ami (beloved). But he would soon acquire a sadder tag, Le Fou- the madman.

The problems first emerged in 1392, when Charles was 23. Riding into Brittany in July of that year on a mission to arrest the attempted murderer of one of his administrators, he lapsed into a psychotic episode and started wildly attacking his own knights with a sword, killing five of them. Restrained, he fell into a coma and it was some time before he came to his senses, but episodes would continue throughout the year and into the next. Exactly what was wrong with Charles VI is unclear. His specific diagnosis is impossible at such a distance, and the symptoms varied over time. He would alternate between periods of lucidity and ranting lunacy with terrifyingly unpredictable infrequency. Sometimes he would run down the halls of the palace howling like a wolf. At other times he would be otherwise functional but would forget who his wife and children were. At one point, he apparently decided he was made of glass and ordered iron rods sewn into his clothing. The symptoms taken together don’t add up to a coherent whole, and modern commentators have suggested everything from schizophrenia to bipolar disorder.

No one quite knew what to do. England was fortunately undergoing its own crises and not able to take advantage of the situation, but clearly a mad king was a problem. The doctors could do little, and in light of their failure a spiritual etiology for the king’s condition suggested itself. Some demon had possessed Charles, or some sorcery.

The 14th century was both glorious and decadent, a time of brilliant advances in learning bound up with the revival of darker forces from the past. It didn’t help that the French monarchy’s Avignon Papacy project had by now degenerated into two rival popes, one in France and the other in Rome, each declaring the other a fraud, a period known as the Western Schism. The ruling houses of Europe backed one or the other as political necessity dictated. With traditional spiritual authority in crisis, people turned to less conventional solutions to their problems. For the peasantry, older practices reasserted themselves in daily life- divination, necromancy, and undisguised witchcraft, colored by both Christian ideas and dimly remembered hints from the distant pagan past. For those with more education, books were available making use of sciences like astrology and alchemy to harness spiritual forces to the apt scholar’s ends. Magic was everywhere, and everywhere there was ambiguity and uncertainty, both cause and effect of the general spiritual malaise. Lords would burn hedge-witches at the stake in the morning and hold court with their personal diviners in the afternoon. All sorts of lines were blurred and reality distorted, a confusion mirrored in the fractured-glass of the mad king’s mind.

Naturally, the king’s illness was ascribed to black magic, and rival parties were quick to blame each other for it. Charles had a collection of powerful uncles, an assertive wife, Isabeau of Bavaria, and others all jockeying for power in his court. But of all the figures scheming around Charles VI in this period the most conspicuous and controversial was his younger brother, Louis, Duke of Orleans. Louis remains an complex, enigmatic and ambiguous figure. Everything about him has to be sifted through a great mound of propaganda as well as nebulous hints and rumors floating up from the depths of six centuries. That he was ambitious is clear, also that he was more than a bit venal. Chroniclers of the period like Froissart and the Monk of St. Denis accuse him of taking advantage of the king’s illness to impose huge taxes, the proceeds of which he directed his way. He is also accused of having comforted the queen in a more-than-brother-in-law-like way. He and his wife, a Lombard noblewoman with the wonderful Bond-girl-esque name of Valentina Visconti, were widely held to be neck-deep in magic. People noticed that while the king might not remember his shrewish wife’s name he was never so mad that he forgot the lovely Duchess.

Above: A scientific reconstruction of what scholars believe Valentina Visconti looked like in life.

But from a distance things seem less clear. In one sense Louis’ unpopular taxes were in keeping with the centralization program that had been the project of French royal power for at least the last century. People in France thought his wife was a witch, but they tended to think that about Italians generally.1 That Louis wanted power is certain, but so did everyone else, and what makes him distinct in that regard is not his ambition but his failure to avoid accountability. In many ways, Louis simply became the face of the general decadence and selfishness that characterized the French court of the period, and for one very good reason, an episode that epitomized the age.

In January of 1393, one of Queen Isabeau’s attendants was getting remarried following the death of her second husband. To celebrate the occasion, the court decided to throw a party, which would have the secondary purpose of amusing the king and easing the burdens on his troubled mind. It is unclear who exactly was behind the specific plans, but at some point it was decided, possibly by the king himself, that the king and five of his closest friends would dress up in costumes with their identities hidden, and part of the fun would be for the partiers to guess who they were. For the occasion, they would play the part of wild men.

Wild men were an extremely common theme in medieval lore, one strangely overlooked today. In essence, a wild man (or wodewose) was conceptually a kind of sasquatch/caveman hybrid, something both primitive and fae that occupied the dark places beyond civilization. Every medieval society had stories about them, and the concept can be traced back to Roman times and earlier. There was a paradoxical aspect to their nature, though wild and lusty, the wild men possessed a kind of primordial wisdom. In some stories, if you got them drunk, you could capture them and make them reveal esoteric secrets. In peasant rituals it was common to dress up as wild men and, suitably disguised, poor abuse on members of the community who ran afoul of social norms- like marrying too many times- a practice known as a charivari. In some rituals, wild men were burned in effigy in order to release, by way of sympathetic magic, their arcane power.

It seems that the plan was for the king and some of his friends to dress up as these wild men, mock the lady-in-waiting for her lustiness, and invite everyone to guess who they were. For verisimilitude, the costumes would be made of linen covered with shaggy hemp. The hemp would be attached with pitch. The planners were fully aware that this made everything extremely combustible and they specified to the guests that no one was to come near the wild men with any open flames.

All went well at first. The king and his friends rushed into the party dressed like savage half-men, roaring and making obscene jokes. Everyone was laughing and trying to figure out their identities. It was at this point that Louis arrived. He was late to the party and apparently hadn’t heard the rule about the torches, and he approached with one in his hand. Before anyone could say anything, the wild men were ablaze. The king was saved when the Duchess of Berry, his aunt, threw her dress over him and smothered the flames. Another man managed to dive into a barrel of wine. But the other four wild men were burned alive before the horrified guests. Thus ended what became known, infamously, as the Bal des Ardents, the Ball of the Burning Men.

Louis was obviously blamed for the tragedy, but it remains unclear exactly what transpired. All accounts have Louis holding the torch, but some specify that he threw it, as if intending to light the king on fire. J. R. Veenstra, author of the study Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France, gives a fuller context for the traditional charivari, explaining it in terms of the tensions it represented in the medieval imagination between Christian orthodoxy and the older recesses of paganism, some traditional, some newly rediscovered. Louis also, in his view, was a man of such contradictions, a magnate both interested in and repelled by sorcery. In addition, he had a complex relationship with a brother who was both more powerful than he but far less able to control things, whose madness must have seemed like the reproach of God on France. Did Louis choose, at that moment, with that particular ritual being played out before him, to attempt to exorcise the demons plaguing himself, his family, and his nation?

If so, it failed. The king lived, Louis was publicly penitent, and nothing was resolved. The king sank further into madness and his personal authority collapsed. In this vacuum two primary factions emerged. One was led by Louis. The other was headed by John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. The latter was a grandson of Jean II who had married the widowed Duchess of Burgundy and then married off his younger son Philip the Bold to the only daughter of the Count of Flanders. This consolidated a vast amount of territory under John the Fearless, and along with Edward III’s line he nursed credible dreams of becoming king of France as well. The animosity between the two men degenerated to the point that John openly had Louis assassinated in 1407. Louis’ son Charles then joined forces with his father-in-law the Count of Armagnac, and civil war ensued.

Burgundy was complicated.

Burgundy joined forces with a newly-aggressive England, this time led by Henry V, son of the usurping Henry IV, formerly the Duke of Lancaster. Henry was pressing the traditional claim to the throne of France but despite having less legitimacy was far more ruthless and talented than his predecessors. With the help of Burgundy, he torched his way through France, defeated the French at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, and forced the mad Charles VI to disinherit his own son (the pretext being that he was actually the son of Louis), hand over his daughter Catharine to Henry as a wife, and proclaim his new son-in-law the next king of France. It must have looked like the cursed century was finally culminating in the end of that unfortunate kingdom’s independent existence. The mad reign of poor Charles VI was the nadir of medieval France.

Yes, Henry V is the king from … The King.

Then, in a small town called Domremy, far from the intrigues at court, a teenaged girl had a series of visions of several saints and angels who told her to save her country. Jehanne D’Arc, better known as Joan of Arc (the ‘Arc’ is obscure) came from a family of small landowners who, like most of the peasantry, had suffered greatly from the machinations of the powerful. Accepting without hesitation that she was on a mission from God, she talked her way into a meeting with the disinherited former prince, the would-be Charles VII, and convinced him to send her with the remainder of his army to relieve his forces besieged at Orleans. Joan lifted the morale of the largely beaten force, and they not only broke the siege but began to turn the tide. Henry died at the age of 35, worn out from battle and disease, two months before Charles VI. This left only Henry’s infant son as a rival, and many of the French who had been cowed by the English warlord defected to Charles, who was finally crowned at Rheims. He was called Charles VII Bien Servi (the well-served).

Shortly thereafter, Joan was captured by the Burgundians, who sold her to the English, who in turn put her on trial as a witch and a heretic. A key feature of the charges was that she had worn men’s clothing. She was forced to deny that God had sent her, which she did at first, but then after some prayer and consideration decided that she was wrong to do so. She publicly stated that the voices she had heard were angels, and the victories she’d inspired were proof enough of her claims. The English burned her at the stake on the 30th of May, 1431. She was perhaps 19.

Joan had grown increasingly aggressive in her final days before her capture, and the diplomacy-minded court of Charles VII had kept its distance from her. He did little, if anything, to help her once she’d been taken. But after her death he worked to rehabilitate her, and she became, in time, France’s greatest saint, La Pucelle (the Maiden), the Maid of Orleans, St. Joan of Arc. She was proclaimed such by the now reunited Catholic Church, which had meanwhile culled the number of simultaneous popes from a high of three to the more customary one in 1417. The English would never regain their momentum in France and were driven out (apart from Calais) by 1453. Burgundy would, a century hence, cease to be a powerful, independent state, instead parceled out between France, the Low Countries, and the Holy Roman Empire. The Kings of France would have heirs from then on, up until the Revolution.

She’s who you turn to when you’re tired of foreigners trashing your country.

If the burning of innocent men began the curse, the willing sacrifice of a pure-hearted maiden consigning herself to the flames was perhaps what broke it. Fire, as a theme, appears again and again in this tale. Witches are burned, lovers are burned, France is burned- even the king himself. But nothing can rectify evil but goodness, and no punishment or purging could suffice where selfless love was needed. That one teenaged peasant girl willing to die for God could undo the serial decadence of generations of God’s anointed kings is itself a miracle worth pondering. But perhaps that’s unwarranted speculation, and economic factors and global cooling had more to do with it. Everyone knows that curses aren’t real.

My source for much of this is the excellent Magic and Divination in the Courts of Burgundy and France, by J. R. Veenstra. See page 84 for French attitudes toward Visconti’s native Lombardy.

For further reading see the following:

Desmond Seward- The Monks of War; The Hundred-Years War; Henry V as Warlord.

Froissart- Chronicles.

Source: The Library of Celaeno

Comments

Post a Comment