Fake Lit and the Curation of History

Fake Lit and the Curation of History

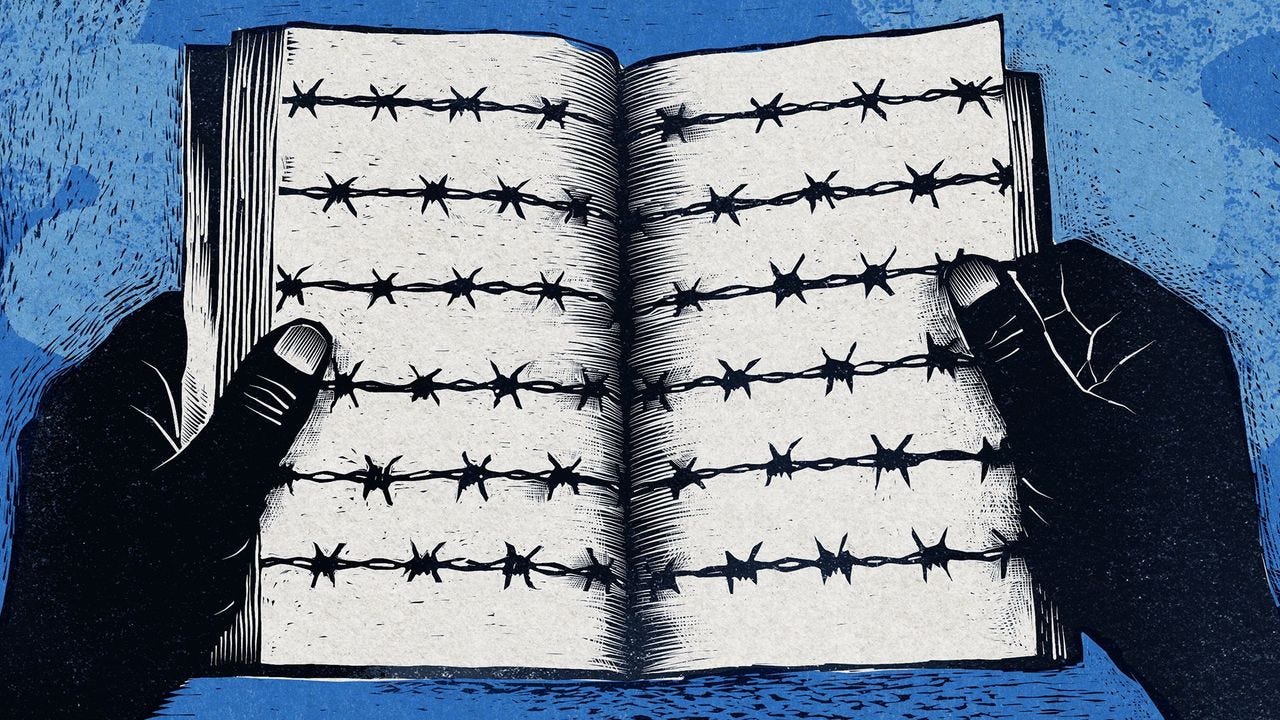

We may need to pay closer attention to the shelves in our bookshops. The construction of the pseudo-reality is entering its secondary phase: the curation of historical amnesia and myopia.

John Waters

The Darker Side of Bad Books

There is an aspect of propaganda to which we may be paying insufficient attention: the curation of history.

Through the work of Mattias Desmet and others, we are pretty much on top of the quotidian drip of news-management, indoctrination, misdirection, disinformation and normalisation disguised as warnings about malinformation or ‘conspiracy theory’, and other delightful skills of the contemporary nudge-monger. But we forget that what is happening is intended to be for keeps. It is not, in other words, as if, when the would-be tyrants have achieved their objectives, they will call an end to the lying and brainwashing programmes, and then revert to something resembling what we remember as the way things used to be. We should not forget that what they are constructing is a pseudo-reality, a completely new and — they intend — self-cohering version of the world, which will in time utterly erase all consciousness of the true one. We know from the work of the founding fathers of the science of indoctrination that the most fundamental aspect of propaganda is its total saturation of the space in which its human prey is corralled. The object is not simply to send ‘messages’ but to convince the recipient that what he is observing is reality itself, and for that the message requires to be contained in everything conveying signals to the public, with nothing left lying around that might alert the idle bystander to the existence of something not quite right.

To this end, the Lies require to be total and at least quasi-ubiquitous. It would be pointless to control 99.999 per cent of the mainstream media, for example, if other media were not subject to mechanisms of censorship and control as well. In the context of a cultural understanding whereby anything that does not accord with the ‘reality’ as presented in the mainstream is deemed to be ‘disinformation’, ‘malinformation’ or ‘conspiracy theory’, a certain element of dissenting opinion is permissible on the grounds that it will not be taken seriously. But this must be carefully monitored and controlled in all kinds of unexpected and counter-intuitive ways. By the same token, after a certain honeymoon period, the orchestrators of the Big Lie need to begin focussing on the Big Picture, spreading out into the future. There is no point in telling such a lie in the present only to have it debunked at the remove of a few years, or indeed ever.

It is early days yet, in the present campaign. What we have been observing has been, in a certain sinister sense, impressive in its capacity to persuade the vast bulk of virtually every population that the stage-set they have been focussed on, and all the events and interactions they have observed there, is the truest thing there ever was and ever will be, world without end. With the best will in the world, it is scarcely possible to assert with a straight face that one is free of its influences and insinuations. The chances are that perhaps half or more of our thoughts are perforce directed at things that are not real, or not true, or partly real and partly untrue, or simply scenes played out by actors according to a script that is the realest thing about any of it.

But, beyond this, there is another level. We are four and a half years into the present coup and may be approaching the moment when events cease to be merely quotidian, and start to become a matter of the evolving historical record. Of course, this function would have been within the scope of intentionality from the outset, since it is part of the role of media to provide the ‘first draft of history’, but journalism is generally concerned with the short-term, the microscopic, the episodic and the instant. At a certain point in the creation of a pseudo-reality, this is no longer enough. After all, the Big Lie is for keeps and, once the initial layers are bedded down, it becomes imperative to look to the longer term. There is no point in successfully persuading people of a spurious reality for a succession of days if it begins to fall apart on the larger screens of years or decades. There would be little point in managing the flow of information on a day-to-day basis for a couple of thousand days, for example, if suddenly, out of the blue, a known author were to publish a book in which he or she postulated a version of things purporting to be the actual and full truth, and this book, despite being ignored or dismissed by the purchased mainstream, managed to gain dramatic traction online. In short, the pseudo-reality will continue to be persuasive only if it appears to operate within a historical framework with which it coheres, and for this to occur in the necessary manner, it is imperative that history be moulded into the shapes that are required by the pseudo-reality. Really, the media can do only the initial spadework on public opinion, whereas the matter of the historical record is for the historian, the sociologist, the biographer, the memoirist and the essayist in human behaviour. The task is to catch the punter when he turns off his TV and, seeking a broader view of things, takes a stroll to the bookshop to see what the smart guys are saying.

Although we in the Resistance do not think or talk about it much, we are vaguely aware that the publishing industry is highly controlled, so that, apart from books published independently (and accordingly having to be content with small circulations), there have been few significant works which seek to expose the criminality of the past few years. In a functioning democratic context, there would by now be dozens if not hundreds of such books, but in reality the numbers are so scant that it becomes puzzling as to why there are any at all. A few books — Mattias Desmet’s The Psychology of Totalitarianism is an example — achieved some degree of penetration into the mainstream, but it will not have escaped notice that this book ensured that Desmet came under vicious attack from both the mainstream and his own supposed side. Laura Dodsworth’s April 2021 book, A State of Fear, which exposed the UK government’s use of totalitarian tactics against the public, is another, and again caused a ripple of muttering that might be seen as a chink of light or a controlled explosion of the potential disquiet. There were other ‘instant’ books which essentially assembled factual accounts of events shortly after they unfolded, but none of these has yet captured the public imagination beyond a tiny partisan fringe.

Nor have there been many credible books which do more than affirm the lie in a rather banal and side-swiping manner. There have been no great works which replicate in book form the essential narrative of the Covid crime — books, for example, about the heroic fight to save humanity from a deadly virus, which remains the implicit narrative of the purchased media. There is here, then, a serious lacuna which leaves open the possibility of an eventual disintegrating the pseudo-reality. For why, if the narrative is true, are there not more triumphant accounts of how the war was won and humanity saved?

There is some incidental traffic that glances tangentially off the quotidian and, in doing so, creates a sense of the lie as a truth receding backwards into history. The credulity of authors, as members of the mesmerisable public, achieves a certain amount by the dropping of incidental references to such as ‘the pandemic’ or ‘the Covid’ into otherwise unrelated works. Tragically, Faith, Hope and Carnage, the 2022 book-length interview, with the great Nick Cave by the Observer journalist Seán O’Hagan, provides one such example, with Cave rambling on about how he got through the pandemic, and reflecting straight-faced on humanity’s near-miss with dying of a head cold. Those interviews were conducted right through the early stages of the Covid coup, and accordingly have a real-time sense of actually exiting reality, and as such are gold dust from the viewpoint of the orchestrators of the lie — but they are at this stage incapable of repetition or emulation.

There is therefore a need for other forms of what we shall loosely call literature, without which the pseudo-reality might be in danger of falling at some future moment, perhaps by dint of the syndrome originating in the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, popularly recalled as ‘the dog not barking’. The aim here is to create a sense of narrative normalisation — not so much to add anything as to present material about the Time of Covid which treats of the circumstances of that period in a manner that is plausibly incidental, and therefore all the more likely to be persuasive. A collateral effect of this mechanism is such as to invoke amnesia concerning matters which do not fit this narrative.

The principal urgency is to dispel belief in ‘conspiracy theories’, which is to say matters that, while real and true in substance and implication, are denied by the orchestrators and are therefore not happening. The adequate curation of the historical lie will here require the commissioning of numerous books — fiction or fact, it hardly matters — in which such things that we know or suspect to be happening now are not mentioned, or in which things are mentioned that are not happening, or in which happenings, real or invented, are presented with no more than a tone of matter-of-factness, or which elaborately describe realities in a partial way, but eliding the inconvenient rumour or hypothesis, but still filling in any emerging cracks in the facade of the lie by simply repeating one or more of the main strands of the lie in a kind of noncommittal, commonplace manner, so it does not appear that anybody is raising a sweat trying to justify or defend something that is supposed to be no more nor less than the actual factual truth.

I sense that this is already in hand. Last year’s Booker prizewinner, Prophet Song, by the Irish writer Paul Lynch, had all the hallmarks of being written to order as part of the pseudo-reality. This may or may not be the case — it may well have been written spontaneously as a consequence of some degree of ideological disposition serving to ensure the author’s acceptance of a particular prevailing narrative — but this hardly matters, since a book written by a passionate believer is likely to be at least as convincing as one written by a purchased cynic. As I’ve written here previously, that novel — written at the height of the Covid crime — deals with the suspension of democracy in the wake of a coup in Ireland — arising from a far-right fascistic insurgency. In other words, let us decide, the book anticipated the propaganda requirements of the orchestrators of the Covid coup, and as a result now exists as a kind of witness to something that never happened or never surfaced as a credible possibility — indeed, something that might well be described as the opposite of what actually occurred, and therefore extending something of an alibi to the perpetrators of the actual coup of the spring of 2020. Despite the glaringly obvious circumstances, and to the great credit of the orchestrators, the announcement of the winner was accompanied by oceans of commentary which made Lynch out to be the new Orwell. For those who missed it, here is my account of that affair.

It is surely obvious that, if the orchestrators of the coup against the peoples of the democratic world are serious in their endeavour, they need to ensure that there are many more such books by which to continue blocking out any holes in their pseudo-reality. The media, it must be conceded, do an excellent job of curating public opinion on a day-to-day basis, but this will decline in efficacy unless the version of unfolding historical reality being purveyed is overwhelmingly in tune with what the purchased journaliars are asserting as fact.

I do not have the stomach these days for visiting bookshops as much as I used to. But I do know that such books have already started to appear. Unless you know what to look for, they will not draw your attention for this particular reason. They will look, more or less, just like books always did. They will be plausibly presented, with attractive cover designs and blurbs on the back comprising something clever to draw you in.

Recently, someone made me a present of a book about neoliberalism by two high-profile leftists, the American filmmaker Peter Hutchison and the Guardian columnist, George Monbiot. I was only vaguely aware of Hutchison, but Monbiot I already knew as a somewhat myopic leftist observer of social, economic and political affairs, albeit with an occasional pretty turn of phrase. Despite my obvious reservations, I resolved to read the book, as neoliberalism is a topic that has loomed ever larger in my consciousness in the past four years.

The book is called The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism, and I had barely got through the cover blurb when it struck me that this could be one of the most important books of our age, an age in which, as I have been writing here for the past four years, the notion of the rich getting rich and the poor getting poorer has lately entered the realm of the incredible.

The back cover boasts no less than eight endorsements by noted luminaries — impressive for a first edition. I confess that I recognised only one of the names, that of the Grecian economist, Yanis Varoufakis, who described the book as ‘the definitive short history of the neoliberal confidence trick’.

Less luminous contributors described the book as ‘explosive and beautifully told’, ‘the book we have been waiting for’, ‘really the ultimate crime novel, one in which we all play a part’, ‘an urgent unmasking of some of the most powerful and insidious yet overlooked ideas of our era’, and ‘an unsparing anatomy of the great ideological beast stalking our times’.

I could not wait to read the book, since any one of those accolades seemed to invoke a study of neoliberalism and its downstream effects that I believe needs to be written around about now.

Never has such a book more urgently required to be written and read, and that urgency grows with every passing day. For what we deal with now is not even the age-old problem of ‘the rich getting richer and the poor poorer’, but the manner in which this syndrome has in recent years gotten off whatever long leash it had been on. What we deal with now is not even about ‘the rich’ — in the sense of big houses, cars, boats, private planes, and otherwise ‘expensive’ lifestyles, while the poor die in sometimes literal ditches — it is about dominion through money, and at a level both unimaginable and terrifying. As I have outlined at some depth in previous articles, this has been a feature of economic reality for several decades, but nothing like what occurred in the course of the Covid coup and its aftermath, when most of the world’s richest operators multiplied their wealth by telephone numbers, while millions of small businesses went under.

A book about neoliberalism, I instantly decided, would be the ideal vehicle to deal with the reasons for and implications of this phenomenon.

But the promise of The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism was — at one level — far more intriguing than it turned out. For this is a book not about the situation now pertaining, but a book written as if the past four and half years had not happened at all. It is a book that could have been written at any time between 2016 and the end of 2019 — and much of the time feels like that is exactly what it is.

The actual demeanour of the book in itself ought to have borne a warning. For a subject with such implications for the present moment, it is a surprisingly slim volume:162 pages of text, with large type and an average of less than 300 words to the page, little more than 50,000 words when you count the blank pages.

To explore the significance of neoliberalism to the present moment, you would need to get to the bottom of a number of perplexing conundrums. One of these is how it came to pass that, in a time of unprecedented cultural emphasis on equality, the richest people in the world became exponentially richer. Another is how the conditions for these explosions of fortune were put in place by supposedly democratic governments suspending their constitutions, charters and bills of rights, and tying the hands and feet of their peoples while the robber barons got on with their plunder. Another is how this happened without provoking undue commentary from a largely left-liberal press. Another is why, far from provoking rage and denunciation from the political left, the evidence was of some kind of symbiosis between the emerging new oligarchs and the new brand of leftism beginning to move into the spaces left vacant when the old left went missing following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Indeed, a central question for such a book might be: Where did the old left go to? Yet another pressing question concerns the silence exhibited by many left liberals in the face of the unchallenged wholesale takeover of technology by Silicon Valley and its allies in the early years of the third millennium, a turn of events that created the perfect conditions for the efficient staging of a coup in which propaganda and fear porn were to be among the primary weapons of war.

Alas, the book is not what its cover blurbs promise. It is neither explosive nor beautifully told, but pedestrian and prosaically written. It is not the book we have been waiting for -~ we continue to wait. The Ultimate Crime still remains to be properly investigated, never mind solved. The anatomy presented is not of the actual beast now stalking the world, but of a beast that is long dead in the sense that the dangers of neoliberalism exposed by Monbiot/Hutchison are axiomatically of the distant past.

Most of the ‘villains’ in The Invisible Doctrine are long dead, whereas only a couple of the present villains get as much as a mention.

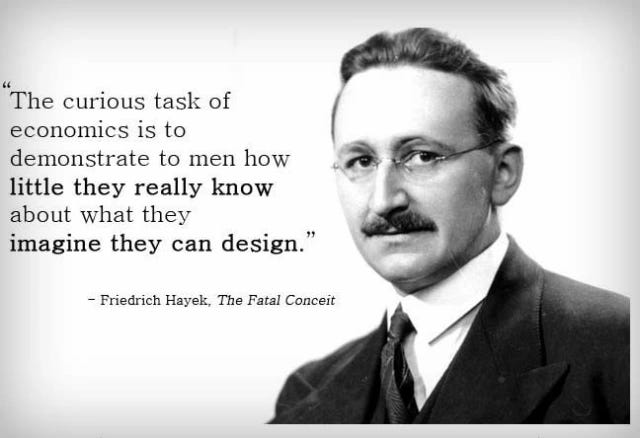

The book’s sights are set, first of all, on the Austrian-born economist, Friedrich von Hayek, deemed to be the ‘godfather of neoliberalism’, by which is meant that he spelled out most coherently and essentially the argument for freedom expressed in terms of economics and money.

The tenor of the book is to imply that the ‘freedom’ invoked by von Hayek and others was always bogus, and that he himself was insincere, perhaps even a supporter of fascism. The marker was never ‘free’, and those claiming they wanted it that way were engaging in deception. In truth, they didn’t ever welcome competition, so long as its absence favoured themselves. Their ideal was not so much a ’free market’ as a market controlled in a manner that benefitted themselves. There is a degree of truth in these charges, but it has nothing to do with Friedrich von Hayek or his philosophy or his work. Although this book seeks to smear him as something of a fraud, he was in truth both brilliant and sincere. It would take several thousand words to elaborate on the entirety of his philosophy, and perhaps that might be the subject of a subsequent article. For now, I simply wish to draw a brief sketch to demonstrate that The Invisible Doctrine is both unfair to him and guilty of misleading its readers as to the virtue and value of his work.

Briefly, for now: Friedrich von Hayek was essentially a liberal, albeit of the classical kind. He was neither a conservative nor a right-winger of any description. At the centre of his understanding of liberalism was a fundamental principle that, once adumbrated, renders clear that liberalism and leftism are incompatible bedfellows — as he put it: ’that in the ordering of our affairs we should make as much use as possible of the spontaneous forces of society, and resort as little as possible to coercion.’ This principle might instantly be recognised as the declaration of the antithesis of what occurred through Western civilisation in 2020.

Money, he insisted, was a critical instrument of human freedom, and ought not to be disparaged or dismissed. It is a mistake to ‘hate’ money on account of the manner in which its limitation had become the source of so much containment imposed on humanity, for, properly understood and administered, it is ‘one of the greatest instruments of freedom ever invented by man,’ conferring, he declared, an astonishing range or choices on even a poor man.

Hayek called it ‘spontaneous order’ — the idea that the very thoughts and behaviours of human beings create their own order and symmetry, and can accordingly, because of the intelligent action arising from spontaneous desire, create a more orderly and functional system of organisation than the most elaborate process of planning. Decentralised, bottom-up processes of decision-making are far more likely to be workable than top-down mechanisms enforced by communal power exercised arbitrary. Human transactions through the ages are what have constructed our understandings of economics, encoding all kinds of motivations, behaviours, responses and impulses, and this information is far smarter than any individual, board, government or committee.

By ‘serfdom’, as in the title of his most famous book, The Road to Serfdom, Hayek referred to the controlled citizen under socialism, deprived of autonomy, and therefore of the possibility of spontaneity. Since the word ‘serfdom’ has profound links to feudalism, it seems archaic in the contemporary world, and yet the idea of an eruption of ‘neo-feudalism’ has been widely canvassed in the past four years, as per, for example, the 2020 book of Joel Kotkin, The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, which I have reviewed here.

A centralised economy, Hayek believed, ipso facto drifted towards feudalism/totalitarianism, because it implied a few controllers having absolute power over everyone else. State power should therefore be minimised, and individual freedom held as the highest value. (True) Liberalism, he stressed, regards competition as superior not only because in most circumstances it is the most efficient method known but because it is the only method which does not require ‘the coercive or arbitrary intervention of authority.’ It dispenses with the need for ‘conscious social control’ and gives individuals a chance to decide ‘whether the prospects of a particular occupation are sufficient to compensate for the disadvantages connected with it.’

Nothing in these fundamentals, he wrote, necessarily precludes government interference. There is scope for such intervention in such contexts as limiting working hours, preventing fraud and deception, guarding against the emergence of monopolies, providing social services, extending supports to the weak and the old, policing ecological accountability, and many other areas where the conditions for the proper working of competition cannot be created without some form of regulation. He even tentatively proposed a form of universal basic income as a safety-net to ensure that nobody remained in absolute poverty, though he would have shuddered at the idea of its being accompanied by minute-to-minute surveillance and social credit scores. ’The successful use of competition as the principle of social organization,’ he wrote in The Road to Serfdom, ‘precludes certain types of coercive interference with economic life, but it admits of others which sometimes may very considerably assist its work and even requires certain kinds of government action.’ Although he said all these things clearly, it is remarkable how many of his critics are able to find on his work only a market purism which insists on competition at all costs, and how so many of his supposed followers have come to much the same mistaken conclusion.

Hayek’s great bugbears were collectivism and centralised planning and control. Collectivism, he stressed, had nowhere emerged from the working classes but was always a creation of the intelligentsia, whom he called ‘second-hand dealers in ideas.’ He had in mind here journalists, teachers, ministers, radio commentators, cartoonists and artists — all ‘masters of the technique of conveying ideas but . . . usually amateurs so far as the substance of what they convey is concerned.’

At the back of all objections to Hayek’s view of the world is the shadow of Marxism, which advanced an entirely contrary idea; that social and economic order could be better achieved by centralised planning, with government having a central role in managing human interactions so as to avoid unfairness and imbalances. Hayek argued that such a system was doomed to fail because, in a complex interaction of multiple factors, it is not possible for a small group of men to match the wisdom of the many through the ages. By virtue of the inevitability of failure, he said, tyranny becomes inevitable. Only the maximum freedom of humanity, he said, would guarantee the absence of distortions, self-interests, corruption and coercion.

This, really, is the subtext of The Invisible Doctrine: It is a defence of the Marxist worldview, and as such as though unconsciously or collaterally buttresses the present unfolding tyranny menacing the West, which seeks to utilise a Marxian software in order to achieve a new material power-grid amounting to an end-of-history control-system of monopoly capitalism.

Although the two books are obviously quite different — one, for example, is fiction, the other non-fiction — The Invisible Doctrine has a number of features in common with Prophet Song. It first of all, and primarily, tells a story that is bogus (the risk from neoliberal thinking as though we had never left the 1980s); raises a host of bogus bogeymen (and bogeywomen) about whom the world should seemingly become incensed all over again; builds an elaborate edifice of misdirection, which of its essence conveys the impression of capturing reality, whereas it is in fact avoiding it; plays to an audience that has already manifested and can be relied on to affirm what it receives. Moreover it ignores what is actually happening: Prophet Song told the story of a coup against a democratic government, but was written in the midst of one by a ‘democratic’ government on behalf of robber barons, whereas the Invisible Doctrine stirs up a head of steam about a danger from neoliberalism that has already hit landfall, albeit not in the manner the authors are keen to acknowledge or insinuate. Both books, in short, amount to exercises in misdirection and normalisation, because they play ducks and drakes with the actual facts of our lives now, in a manner that can only sow confusion and misunderstanding.

Of course, as already stated, what is called neoliberalism simply refers to the ideological backdrop whereby the rich get richer (and the poor consequently poorer, for the second follows from the first as cart follows horse). Neoliberalism has long been a bugbear of leftists, because they (often accurately) perceive it as a way to rig the capitalist game while screaming Freedom! at anyone who objects. This is the view taken by Monbiot and Hutchison, and I have no problem with it. Among the objections expressed in the book are the fairly standard ones that neoliberalism imposes on economic thought a prejudice against state intervention, even when this might be deemed essential in the provision of basic services and catering to the needs of the most vulnerable. In this book is added the complaint that neoliberals are perfectly happy for the state to become involved in economics provided it is to their advantage. Such charges are legitimate in as far as they related to the political behaviour of those who claim to subscribe to neoliberal ideals but in reality tend more towards making things up to suit themselves. The neoliberal ideal, rooted in the ideas of the Austrian School, and in particular the work of Friedrich von Hayek, is quite a different matter, and this book is not good at making that distinction. But, still, in a certain sense, that is not my concern; though a fan of Hayek, I do not list this as a primary flaw or weakness of the book, merely as an argument I disagree with. Hayek’s works are well able to stand up for him, and, to the extent that the imbalance arising from this book needs to be addressed on this score, I could easily deal with it by writing a different kind of article, one titled perhaps, ‘What Hayek really believed’, something I might very well do before too long.

And nor would I suggest that there is nothing worthwhile in The Invisible Doctrine. Its exposition of the rise of neoliberalism out of the WWII thoughts of Hayek — concerning how control-based economics might prudently be avoided once peace returned — is useful and generally quite objective, though it misses that Hayek was a philosopher as much as an economist, and all the implications of that. And, although it fails to emphasise sufficiently the distinction to be made between Hayek and the (largely self-nominated) acolytes and followers who came afterwards, a good case is made to the effect that Hayek’s correlating of markets and freedom came to be abused wholesale in more recent times, as ‘think-tanks’ comprising actors presenting as his devotees sought to infiltrate politics, buy journalists, and generally go to any lengths to misrepresent and re-appropriate his ideas. For example, his insight about money being an ideal emblem of the spontaneity of human beings was never intended to advocate the total absence of state oversight, a fallacy which the book treats throughout as virtually his core principle.

I am, it is true, irritated by the reductionism of the Monbiot/Hutchison characterisation of Hayek as a friend of the rich and to hell with the poor. That is the last thing he was. When he spoke about Liberty, he spoke sincerely, and indeed there is in his works, particularly The Road to Serfdom, as much treatment of totalitarianism and the other consequences of unfreedom as about the values he sought to exalt and uphold. In a contest for the better advocate of freedom, Hayek would win hands-down over Monbiot and Hutchison.

These are, as I say, merely arguments with the content of the book, an indication that it has some interesting and provocative material. My gripe is not so much with the content, however, as the things it does not contain. The Invisible Doctrine, I would say, is weak on making distinctions between the foundational thought of neoliberalism and the distortions and abuses which crept in later on. It is, however, useful in outlining and exploring some of these distortions and abuses, even when the authors insist on attacking certain categories of actors and not others, in tune what emerges as a pretty predictable outlook. You can take the book’s temperature by looking at what and whom it attacks: utterly predictable targets in the context of the framework just outlined. Hence, there is the usual knockabout stuff about Donald Trump, Boris Johnson and Viktor Orbán, as well as Brexit, ‘conspiracy theorists’ and ‘anti-vaxxers’. Every reference in the book to Covid is noncommittal except to the extent of disparaging anyone who failed to believe it was the most dangerous disease to hit the world ever.

But, as already intimated, what irritates me about this book is not so much anything that it contains (although there are several annoying tendencies which seem designed to turn off about half the book’s potential readership.) The problem resides, in the first instance, with matters which one might have expected to be dealt with in a book like this on account of its timing in the present moment, but are not even mentioned. Had I been presented with the manuscript of this book as an editor or publisher, I would have rejected it on the grounds solely that it is merely half-finished. The authors have no more than set out the parameters of their argument, but have failed to engage with the true locus of the danger of the undoubted corruption that has been perpetrated on liberal ideas of economics in practice, the unprecedented consequences which are to be observed at full virulence in the current state of — in particular — the former Free World, in effect the total and terminal bolting of the neoliberal project.

In the normal run of events, since we now live in an era when the richest people/interests in the world now own double, treble or quadruple what they owned only a few years ago, we might expect any book about neoliberalism to deal with the forces which combined to make this possible. You would expect, for example, that closing down the world for two years and driving huge numbers of small and medium-sized businesses to the wall would have been a central feature of any attempt to study the downstream consequences of neoliberalism, and perhaps also the actions of ‘philanthropists’ who, though medically unqualified, had acquired the gift of predicting pandemics and other alleged disasters long before they happen, and — lack of expertise notwithstanding — are given pride of place on the world’s stages (including, indeed markedly, the Guardian) to make their case for lockdown and compulsory inoculation.

But no, it’s not that kind of book about neoliberalism. It’s the kind of book about liberalism that, though published just a couple of months ago, might, in its general content and message, have been published at any time in the 20 years before 2020. In other words, it is an ideologically slanted book, which seeks to draw attention only to factors and operators with which/whom the authors are displeased. Its effect — if not its purpose — is to normalise a situation that could hardly be more abnormal, and in doing so to misdirect public attention away from the true meaning of what has occurred.

And remember, too, the nature of the change that has entered in. We no longer live in the world of 2019, and in far more senses than one. The rich did not become fabulously richer in isolation: they did so in a context where the vast, vast majority of leftists sat on their hands, masked to the eyeballs and berating anyone who wasn’t, jabbed like pincushions and demanding that everyone else receive the same assiduous puncturing. The Left — once the self-appointed guardians of liberty within the capitalist West, had someone seemed to recognise that what happened in the spring of 2020 was not something they ought to rail or revolt against. Somehow, they knew that this was a dance they were supposed to sit out. And so, not only were they not the ones rushing to the barricades to proclaim their undying love for freedom, but they were, in the main, the ones rushing to provide covering fire for the tyrannical authorities — many of them of a left-liberal persuasion, to be sure, but not a few pronounced rightists/‘conservatives’ as well, i.e. the sworn enemies of the Left. And, even when it became clear that what was happening was going to eviscerate many small businesses and the workers who depended on them, to the great enrichment of corporations and their shareholders, almost nobody on the left raised as much as a murmur. Nor had they anything to say about the wholesale culling of the elderly, using protocols involving sedatives and ventilators, in that horrific spring of 2020, nor the rollout of untested injections masquerading as vaccines, which were seen to be causing injury and death virtually from the first day of use.

A central question, for example, might be this: Why did the left cease to represent the blue-collar working class and therefore leave them a-begging for such as what are called ‘far right populists’ to adopt as an opportune client base? Why, for example, was Donald Trump necessary? A related question might be framed as: Why have the chief left-liberal establishments of all Western gone AWOL while the world’s richest robber barons doubled the size of their wads in a period when ‘equality’ was the buzzword-of-choice among said left-liberals?

And an even more central conundrum: why, for more than two decades, did the Left remain largely silent about the emergence of Silicon Valley, and the attendant quasi-monopoly that was to manifest in relation to virtually everything tech-related? Why were Marxists not demanding the ownership of the means of production should reside with the working class? The answer to this question more than hints are the answers to the others: leftists had moved on to the ‘Cultural Marxist’ phase, whereby their client base was not longer the working class, but the basket of minorities now being choreographed to become the new instrument of an ostensibly Marxist takeover, although this time as a Trojan horse in which the beneficiaries would not be the proletariat or working classes, but the tycoons and robber barons who would secrete themselves in the belly of the socialist horse while it was driven into the heart of the once Free West.

The book rather too carefully circumvents these questions, as well as multiple related though possibly lesser ones. It is a book written by two men who are easily categorisable as left-liberals, even from their author blurbs. George Monbiot, as already mentioned, is a Guardian columnist and Peter Hutchison ‘an author, filmmaker and activist’ who once made a film with Noam Chomsky. Nothing wrong with that, of course: Chomsky is an interesting and sometimes wrong footing character, no matter what colour your shirt, but it may be rather more telling that Hutchison had made two films called Healing From Hate and The Cure for Hate. ‘Hate’, we know, has become a Cultural Marxist propaganda code, being reduced to a term for describing only the responses of people discommoded by that increasingly noxious ideology, who are consequently dismissed as seeking to defend their ‘white privilege’ when really they just want to be treated with decency. These tendencies are all over this short book.

Similarly ‘climate change’, even though reputable scientists have pronounced it an unsettled dispute. Any questioning of induced and coerced mass migration is frowned upon, even though the present waves of outsiders arriving in Western countries are clearly being orchestrated — again — by those who have hi-jacked the ideas of Hayek, Mises and Friedman, and see to create a consumer economy devoid of ‘distorting’ factors like patriotism, community-loyalty, and life for the sake of itself. And, of course, the idea of an overarching group of elite controllers of the world is dismissed out of hand, on grounds no more solid than the repugnance of the authors for the type of people advancing them.

The arch-villains of this book are mostly long dead: von Hayek, Friedman, Reagan, Thatcher. There is nothing here about the motherWEFfers, nothing abut Schwab or Soros. Bill Gates gets one slightly dishonourable mention, but only for emitting 7,500 tonnes of CO2 per annum from his private planes and helicopters, and for the effects of a switch to biofuels which is ‘now among the greatest causes of habitat destruction, as forests are felled to produce wood pellets and liquid fuels and soiled as trashed to make biomethane.’ Nothing about the slaughter perpetrated in Africa and India by the Gates Foundation.

In short, this is not, despite its cover blurb, the book the world was waiting for, (albeit mostly without knowing what it was actually waiting for). And, since the current public discussions of all our societies are curated and moderated by people with perspectives not unlike those of its authors, nobody has as yet pointed out that this book is avoiding the hippopotamus in the hallway — i.e. the fact that the world is now about to enter a stage that can only accurately be described as the apotheosis of capitalist acquisition, the very thing you might expect people like Monbiot and Hutchison to anathematise.

Most of all, what the world needed to glean from a book with a title like this one was how and why the authority of democratic peoples was disconnected from the power grid four years ago, and organisations controlled by the world’s richest oligarchs enabled to become plugged in instead. It needed to know how a longtime deep suspicion of capitalism by left-liberals was set aside in favour of a role in cheerleading the coup unleashed from March 2020, or perhaps more correctly from August 2019, when the world’s biggest asset-management company, BlackRock, issued a demand that the global economy be put on life-support against its imminent collapse. It needed to have explained how these developments went unnoticed by the watchdogs of democracy, the once fabled Fourth Estate, which failed to see a news story in a play for total acquisition of the world’s resources by the tiniest number of its denizens. It needed, too, to know why leftists had sat on their hands for a quarter century while ownership and control of the technological wherewithal to lay claim to dominion over all future wealth-creation was allowed to fall into the hands of the monied interests with the capacity to snatch this know-how from the grasp of the democratic realm.

The authors acknowledge that there are ‘oligarchs now in every society’, but fail to identify the concertation of assault that occurred from spring 2020 onwards, centrally under the direction of BlackRock and the WEF. If ever there was a moment to dump the Punch-and-Judy rhetoric and describe what the world’s richest are really up to, this was it. BlackRock receives not a single mention in this book, nor, as noted, does the World Economic Forum, the on-Earth orchestrators of the continuing coup against humanity.

In investing time in a book, a reader enters a worldview that must, at some level, be accepted if the narrative is to remain engaging. Thus, in reading a book comprising such prevarication, even when you know the facts being elided, one of the effects of the book is to arouse an unease in the reader as to the validity of facts or hypotheses which seem like they ought to be in it but are not, and therefore to doubt any prior impression he might have had concerning the nature of what might actually be happening. What is important to grasp is that a book on any subject by a familiar and credible author will convey vast osmotic authority in seeming to debunk rumours or suspicions about nefarious actors arising purely from a book’s failure to allude to these. If the WEF and BlackRock go unmentioned in a book purporting to deal with the baneful aspects of neoliberalism in our time, the reader will be impacted by a strong negative feeling of the WEF’s and BlackRock’s innocence of wrongdoing in this context. This, after all, is ‘the book about neoliberalism we have all been waiting for’

The question of neoliberalism is but a minor sidelight on these massive conundrums. None of them feature, and for a very simple reason: the authors of the books are utterly blind to them, because their preoccupations are rooted in a bygone era of left-right catcalling, long superseded by an entirely different game, which may very well prove to be the endgame of Western civilisation.

Some of us now know why all these things occurred, although many within the Resistance insist upon describing what is happening as the encroachment of ‘communism’. This is to misread the signals, for it is surely improbable that the richest of the rich have decided to throw all their wealth into the pot to be redistributed among the working and welfare classes. Those with eyes to see can now comprehend that the connection has to do with the use of leftist thinking as a software with which to draw in the gullible young and the zombie leftist ‘useful idiots’ in order to ensure the very thing that we have been observing in train: the capitulation of the left in virtually its entirety as the willing accomplices in the greatest act of plunder ever seen in human history. The method was to be leftist — an insinuation of communism/socialism — but the outcome was to be the ultimate capitalist coup: the stealing of the the world’s material wealth, on top of the seizure of the means of production, an exercise already accomplished.

And now we come to the denouement of this strange and long-running saga of illogic: the orchestrators of reality on behalf of the already fabulously rich and close to infinitely powerful have figured out that the leveraging of the ideas of equality, social justice and redistribution may be the key to creating a world more unequal than it has ever been. The promise of ‘progressive’ ideas has been rendered so alluring by our corrupted media that it has become the bait in the most fantastical sociological and financial trap in all of history, which, once sprung, will have transformed the world into a neo-feudal despotism in which the people will ‘own nothing and be happy (in their chains)’, which is precisely the destination warned about by von Hayek in his most famous book, The Road to Serfdom.

The detectable agenda of The Invisible Doctrine is such as to suggest that it is a book that was under discussion for many years, but put on the long finger, possibly because nothing any longer made sense within the old paradigms. As such, it is, at best, utterly otiose. Its publication at this stage, in view of the current slide into left-led tyranny on behalf of decidedly non-collectivist operators, might be deemed negligent and tone-deaf, but in reality its appearance so late into the commencement of an entirely new ideological game suggests it as an exercise in the normalisation of what has occurred, which is to say in propaganda. While there are sections which appear to hold out the promise of a genuinely deep-dive into questions of great import concerning the ideological weather of recent years, an imminent downwards change of gear is always guaranteed even in its most impressive passages, as the familiar cliches beloved of Guardian-readers lie waiting to be rolled out. In such a book, even the partisan sneers and slights would have been tolerable if the hippopotamus in the hallway was at least given a mention, but here they bespeak an exercise in standard political slapstick, with some interesting and well-researched arguments about the impact of neoliberalism — a case undoubtedly worth making — but without the context in reality that would have made of this a unique and timely book.

The Invisible Doctrine seems to be aimed at a reader — if it is aimed at a reader at all — who sits waiting to have his ire stirred up against the bogeymen and bogeywomen of the past, which has the interesting effect of distracting him from what is happening in the present. This is an old game, much favoured by writers for the Guardian, which consists in dividing the analytical field into what the Guardian calls ‘rightwing’ and what the Guardian calls ‘leftwing’: defined more or less broadly as those who blame societal breakdown on family and educational values, and those who blame a societal failure of inclusion. To this list of Commandments has been added, in recent times, cautions against the ‘far right threat to democracy’, climate change, ‘disinformation’ and ‘conspiracy theory.’ All these boxes are dutifully ticked by Monbiot and Hutchison.

While our civilisation is being torn apart by the outworking of their own ideologies, the supposed intellectuals of modern Britain and Ireland continue to spew out the same gibberish that got us into this mess, as if the dateline were 1999 or 1990, or 1984. Largely contextless race conflicts are tearing the cities of both islands apart, as marauding migrant interlopers seek to claim what is the birthright of the indigenous people of these island nations — a massive orchestrated distraction to divert the attention of the public while their birthright is being plundered. Yet, the ‘intellectuals’ bang on about Thatcher and Reagan. Reagan has been dead for two decades, Thatcher for more than one. Friedrich von Hayek has been dead since 1992.

What is at stake here goes way beyond Left and Right. It concerns the very future of the world, and humanity in it. Part of the truth is that, of course, the people I am describing as ‘leftists’, including Monbiot and Hutchison, are not really leftists at all, but merely soft-centred liberals who eschew rigorous ideas of any kind in favour of performative caring that makes them look and feel good. Theirs is an attitude to reality rooted primarily in a desire to attract a certain kind of approval from an audience that pretends to adopt positions inimical to its interests, but always in the knowledge that such ideas will never be implemented. After all, they are not ‘conservatives’, ‘rightwingers’ or anything sordid like that! What they seem not to appreciate is that their myopia leads them to become allies of actors and forces far more sinister than those they ritualistically abominate. Perhaps they thought of this book as simply another routine exercise in pontificating, some further drops of sanctity to add to the reservoir of piety they’ve been topping-up for decades, while the true villains got on with making hay. Perhaps they sincerely do not know what is really happening in the world, though sometimes one gets the impression that they are trimming their diagnoses to suit both their ideologies and their interests.

The authors of this book do not like capitalism which is fair enough. It’s a free country! Ooopps! Sorry, force of habit! What I mean is that suspicion of capitalism was actually a pretty good qualification for anyone writing the book that needed to be written. Yet they failed to write it, and that is something we need to ponder in all its aspects.

Knowingly or not, this book replicates all the non-responses, failures and silences of the left, liberal-left and liberal elements of society in the Covid episode, marking its authors conscription — whether they know it or not — as propagandists. It is a book invisibly subtitled ‘business as usual’ when the end of the world as we know it is staring us in the face. As such it is, even if out of ignorance, an exercise in attempted mass deception. For a writer to allow himself to be recruited to supply sections of the monolith of lies designed to encase humanity in a prison of falsity and misguidance is unpardonable. There is no greater failure in a writer. To conceal it behind a smokescreen of waffle about ‘conspiracy theories’ — even out of unthinking habit — is even worse. The greatest irresponsibility of all is failing to think. While the pimps of the oligarchs flooded the world with fake money in order to set in train the final transfer of all concrete wealth to their clients, these guys were singing the same old songs. As with Prophet Song, we may be dealing with a strange eruption of ideological stupidity, a syndrome which we have long associated — perhaps naively, perhaps not — with, for example, the Guardian.

These are not trivial matters. The risks arising from a poorly researched or thought-through book are not the same here, now, as they might have seemed a decade ago, when we could read an inadequate book and write the waste of time down to experience. A book such as this, intentionally or otherwise, gives succour to the evildoers and assists them in imposing bondage and slavery on humanity. It risks enabling tyranny, or at least greasing its wheels. We cannot state it any more politely than that. To enter into the field of public commentary at a time when the vast swathe of the territory has been commandeered and corrupted, is an even greater responsibility than it has always been, and always is, in peacetime. The consequences of the conspirators achieving the successes they aspire to would be immense and immensely unspeakable for humanity, for they would include the loss of freedoms hard won over 30 centuries, at a cost of millions of gallons of human blood. And now, at a moment when we might have expected to have left all this tyranny and slaughter behind us, we face again an assault, orchestrated by purported authority, seeking to corral, rob, enslave, maim and cull the human population, all behind a veil of corruption purchased with fake money.

What is happening to our world now is terminal in all the ways that matter: terminal of our claims to fundamental rights and protections, terminal to our right to own property, terminal to our bodily integrity, terminal to our capacity to engage freely with other human beings without constant supervision by actors with no conceivable entitlement to conduct this. What is happening is the application of the logic of transitory greed to the economic systems of the world (though especially the West) as a kind of final process of plunder before the entire edifice is changed from one in which human work is central to one in which the human involvement is supplanted with Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), social credit, Universal Basic Income (UB)I, surveillance and, in effect, a total formal and final transfer of the ownership of the means of production from humanity in general to a tiny slice of the species. The idea is that, in the future, most people will own nothing, and will rent whatever they need from their enslavers, who will become omnipotent and virtually deified, and will in time claim rights of dominion over our lives and their duration, our souls and their salvation, and what for the moment we think of — while we are still permitted to — as our minds.

There is no room here for equivocation or evasion. This is not a drill. This is a fight for the very survival of humanity in freedom, something that, as recently as five years ago, we took for granted every living moment of our — had we only known it — relatively trouble-free lives. The last thing we need now is people swamping us in commentary purporting to be rooted in truth, which wittingly or otherwise risks perpetrating the same complacency in a time of — seen in the context of the scale and ruthlessness of the present initiative — the greatest peril the human race has ever faced.

Remember that the orchestrators of the Covid coup have been saturation-washing the zone in propaganda for 54 months. That may mean the authors are entirely innocent of deliberate wrongdoing, but it may also mean that such authors have been specifically promoted on account of their ideological naïveté or myopia.

Source: John Waters Unchained

Comments

Post a Comment