How Christianity rebooted cognitive evolution

Portrait of Augustine, 6th century fresco

Mean cognitive ability fell under Imperial Rome but rose again as the Empire became Christian.

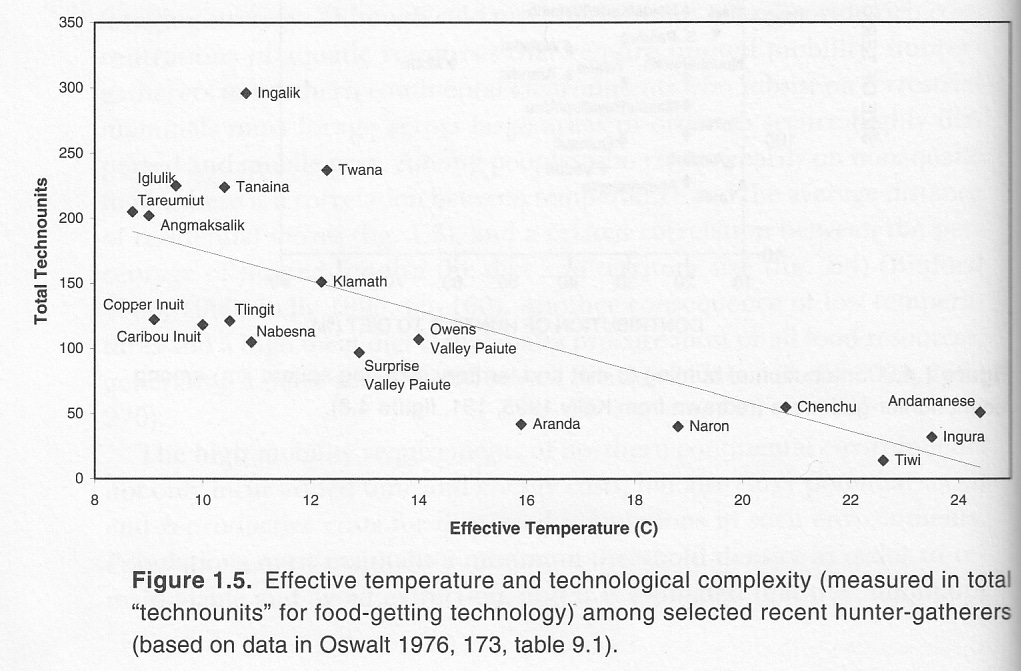

Cognitive ability is the capacity to process information, recognize patterns, and solve problems. It initially served to meet the challenges of hunting and gathering – a way of life that, by 30,000 years ago, spanned the full range of natural environments from the equator to the Arctic.

Colder environments presented a greater number of cognitive challenges, as shown by the inverse correlation between temperature and technological complexity among present-day hunter-gatherer groups (Hoffecker, 2002, p. 10, Figure 1.5).

The coldest and most challenging environments existed during the last ice age, and covered northern Eurasia until about 12,000 years ago. Food was potentially abundant but made up largely of “meat on the hoof” – large herds of wandering reindeer and other herbivores. This food remained out of reach unless one could:

collect, process and remember huge quantities of spatiotemporal data (to track the herds, predict their movements and find one’s way back to camp).

monitor untended traps and snares (to capture solitary animals, which were dispersed over a larger territory than in warmer environments and which took too much time and energy to hunt).

make cold-resistant shelters and clothing.

plan ahead to store fuel for winter and food for times of need.

Other cognitive challenges came from the sexual division of labor. With few opportunities for food gathering, women specialized in higher-order tasks, like weaving, needlework, leatherwork, garment making, pottery, and kiln operation (Frost, 2019).

Farming and Europe’s cognitive revolution

These humans would later enjoy a cognitive advantage when hunting and gathering gave way to farming, which in turn led to greater social complexity – as seen in larger communities, sedentary living, division of labor, State formation, literacy and numeracy, codified law and morality and a more future-oriented culture. There was thus a southward expansion of humans out of northern Eurasia, at the expense of those who, though better adapted climatically, were less able to exploit the possibilities now being created (Frost, 2019).

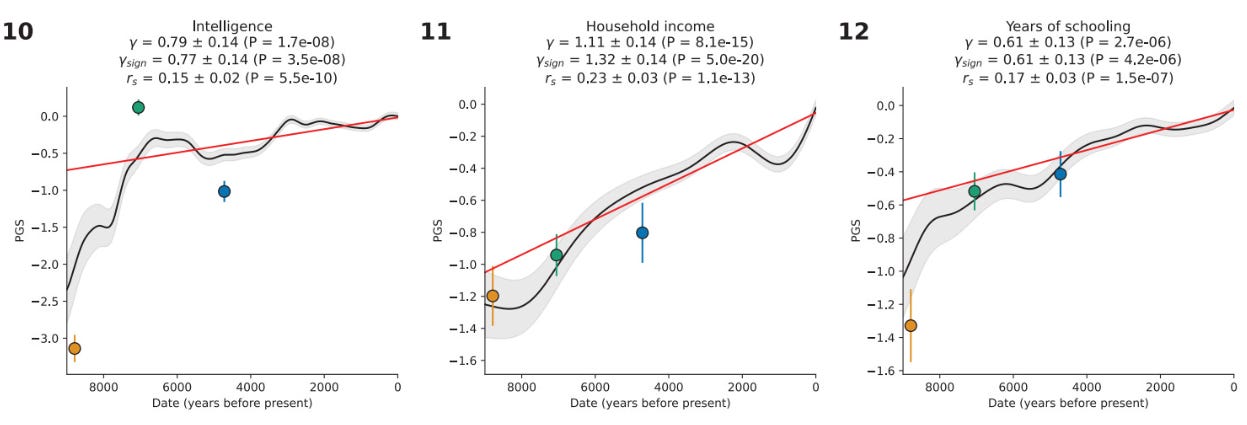

In the case of Europe, we have enough DNA from human remains to chart the evolution of cognitive ability before, during and after the transition to farming. Specifically, we can chart changes over time in the population frequencies of alleles associated with intelligence, fluid intelligence, educational attainment, and household income – all of which are highly correlated with cognitive ability. Of course, these measures may also reflect other mental abilities, like proactiveness and rule-following. If people show initiative and follow the rules, they will go farther at school and earn more money, independently of their cognitive ability.

According to three studies of ancient European DNA, cognitive ability remained unchanged during the long period of hunting and gathering (Akbar et al., 2024; Kuijpers et al., 2022; Piffer et al., 2023). It would be interesting to break the data down by region. Did the hunter-gatherers of central and southern Europe differ from the more Arctic-adapted ones of northern and eastern Europe? Unfortunately, we have much less data from the latter regions.

Cognitive ability began to rise some 10,000 years ago, apparently with the spread of farming into Europe from the Middle East. The rise was especially steep between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago. Was this initial surge due to farming itself? Perhaps. But we should not rule out other causes, like a much larger population with a more complex web of interactions. Nor should we rule out admixture from indigenous hunter-gatherers as a possible cause. Earlier farmers looked distinctly more African than later ones (Angel, 1972; Brace et al., 2006; Frost, 2015). As farmers spread into Europe, they must have mixed more and more with indigenous Europeans.

This admixture is difficult to quantify. One could assume that the Middle Eastern ancestry of farmers would correspond to the genetic difference between them and indigenous hunter-gatherers, but that assumption would be wrong. Some of the difference would also be due to founder effects, and some would be due to natural selection. For instance, haplogroup U is often cited as a genetic marker of indigenous hunter-gatherers, yet it disappeared from Europe long after the transition to farming, probably because it was no longer adaptive (Melchior et al., 2010). This haplogroup shifts the energy balance toward production of body heat – an advantage for people who sleep in makeshift shelters and pursue game in all kinds of weather (Balloux et al., 2009).

The initial surge in cognitive ability may have thus been due to admixture from Arctic-adapted hunter-gatherers who now enjoyed the advantages of farming, including a larger population and sedentary living – both of which would have made them more visible in the archaeological record, including ancient DNA. Hence the steep rise in cognitive ability. The subsequently slower rate of increase might reflect continuing adaptation to the possibilities created by farming.

Changes in European DNA over the last 10,000 years for alleles associated with intelligence, household income, and years of schooling. Note the steep rise when farming replaced hunting and gathering 10,000 to 7,000 years ago. Also note the decline during the time of Imperial Rome (Akbari et al., 2024).

The cognitive decline of Imperial Rome

Cognitive ability steadily rose throughout the Neolithic and into historic times, culminating in the civilizations of Greece and Rome. There was now a flowering of material and intellectual culture. Some people were going far beyond satisfaction of their physical needs and were asking deeper questions about the world. They began laying the groundwork for philosophy, mathematics, history, geography, astronomy and other fields of enquiry.

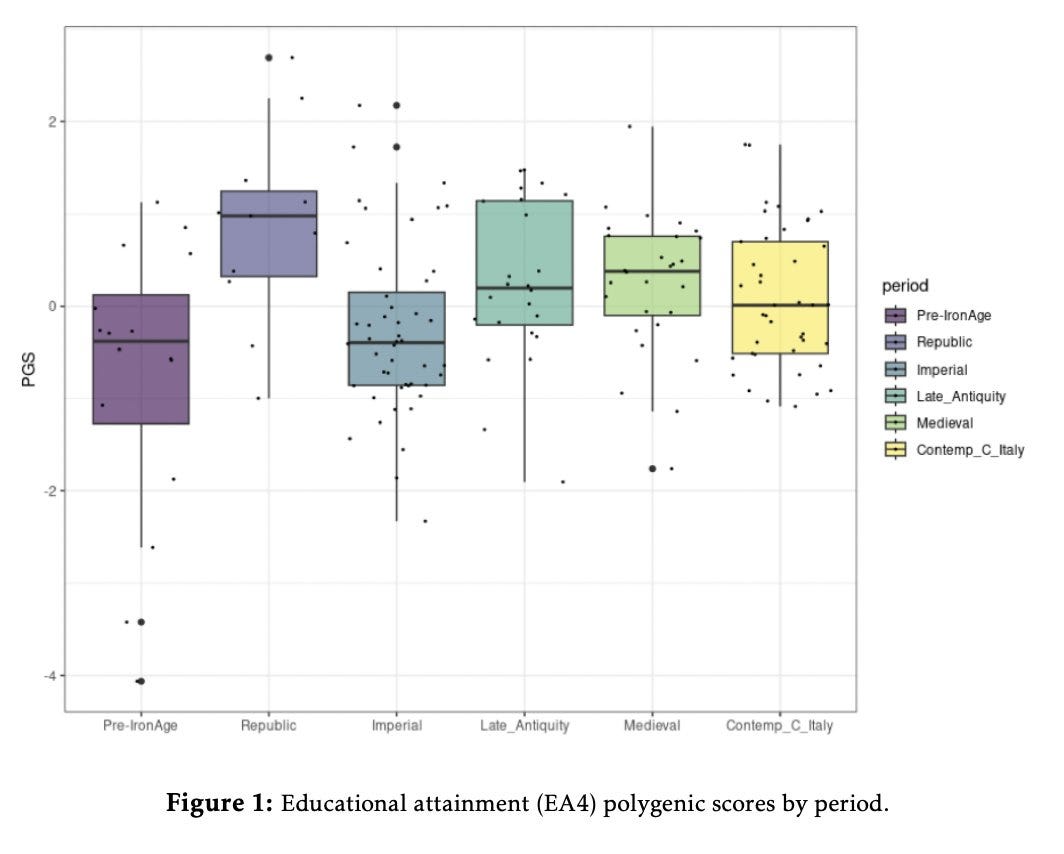

But it was not to last. According to ancient DNA from central Italy, mean cognitive ability rose under the Roman Republic, but then fell sharply under the Roman Empire. It would then rise again from Late Antiquity to post-medieval times (Piffer et al., 2023). The sharp decline of the Imperial Era seems to have been confined to Roman territory, as it does not clearly show up in the first two studies of DNA from Europe as a whole (Kuijpers et al., 2022; Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024), although it does show up in the latest study, which used a larger dataset (Akbar et al., 2024).

There are likely three reasons for the cognitive decline of the Imperial Era:

A decrease in fertility and family formation among the elite (Caldwell, 2004; Hopkins, 1965; Roetzel, 2000, p. 234; Sullivan, 2009, pp. 27-28, 35-38).

Hypogamy between elite men and women of low status, often in the form of polygyny with slave women or newly freed women. The reproductive importance of elite women thus fell (Perry, 2013).

An increase in the slave population, particularly foreign slaves (Harris, 1999), and a resulting disruption of cognitive evolution. Previously, “surplus” elite offspring could always find niches farther down the social ladder. In this way, the lower classes (which had a negative natural increase) were continually replenished by the demographic surplus of the upper classes, as would happen in late medieval and post-medieval England (Clark, 2007; 2009; 2023). This was no longer possible in Imperial Rome because such niches were deemed unfit for upper-class offspring and filled normally by slaves (Frost, 2022). Thus ended the “rinse and repeat” cycle of cognitive evolution.

Rise, fall and renewed rise of mean cognitive ability in central Italy (Piffer et al, 2023, Figure 1)

The Christian reboot of cognitive evolution

The cognitive decline would reverse during Late Antiquity – the period running from 300 to 700 CE and beginning with the recognition of Christianity as a legal faith in 313 and as the State religion in 380. This reversal coincided with the Church’s growing power to intervene in many areas of life, particularly marriage and procreation.

The new faith aggressively promoted monogamy, thus forcing men to focus on procreation with a lawful wife – usually of similar status – rather than on sex with prostitutes or slave women. Successful men were now more likely to pass on the genetic profile that had made them successful. In other words, material success was more efficiently translated into reproductive success … and, hence, into selection for cognitive ability.

Did the Church have that goal in mind? Early Christians certainly understood that some lifestyles are more procreative than others. They also had a basic understanding of population genetics: 1) humans inherit not only physical traits but also mental and behavioral ones; 2) such traits vary not only among individuals but also among populations; and 3) selection for certain mental and behavioral traits will, over successive generations, change the moral character of a population.

These principles of genetics were set forth by Origen of Alexandria (c. 185–253 CE), a theologian who wrote over two thousand treatises on many subjects. Of course, the term “genetics” did not yet exist. He spoke instead of logoi spermatikoi – “the organizing principles of the seed.” As he explained it, “the seed of someone has within itself – still immobile and placed in reserve – the procreator’s organizing principles” (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 3).

This seed, which organizes both body and spirit, is passed down from one’s ancestors:

Just as among the seeds of the body there emerges sometimes, from a great number, a seed endowed with a greater capacity for action, so may we observe the same phenomenon with the seeds of the spirit. What I have said will become clear after what follows: since the procreator has within himself logoi from his ancestors and his collateral lines, it is sometimes his logos that prevails – and the child that comes into the world resembles its procreator – or sometimes the logos of his brother, his father or his uncle, sometimes even his grandfather. This is why those who come into the world resemble one or another [of that line]. We may equally see the wife’s logos prevail, or that of her father, her brother or her grandfather … (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 35-36)

This logos varies among humans:

It is evident that men have not all come into human life with absolutely identical logoi spermatikoi seeded into their souls. (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 5)

Try to imagine whether it is not without reason that God destroys certain seeds in order to prevent the bad ones from multiplying on the earth, once there have been sown those [seeds] whose tendencies are not from the best, and to cultivate the products of superior seeds. This is why the Flood happened, to wipe out the seed of Cain … (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 25)

Another theologian, Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE), likewise understood that people differ inherently in body and spirit, particularly in the power to distinguish good desires from bad ones and the power to put good desires into effect. He initially believed that these powers could be lacking only in a non-Christian, but he later acknowledged that they could be lacking in a Christian too, despite baptism (Pang-White, 2001). Thus, a sinful act may arise from a weakness of will, rather than from a will to do wrong:

Whatever these souls do, if they do it by nature, not by will, that is, if they lack a movement of the spirit [that is] free both to do and not to do, if finally, no power of abstaining from their action is given to them, we cannot consider the sin theirs. (Augustine, Retractationes 1,14, 6)

Although such people are not responsible for their weakness of will or their inability to understand rules, they should nonetheless be shunned and resisted:

… But they are an evil for us if we are enticed and led astray by them; if, however, we are on our guard against them and overcome them, it is an honorable and glorious thing. (Augustine, Retractationes 1,14, 7)

Discussion

Christianity did more than end the cognitive decline of Imperial Rome. It reversed that decline and launched an upward trajectory that would last throughout the Christian Era from Late Antiquity to post-medieval times. Thus, with each generation, the average person became more and more intelligent.

The new faith restarted cognitive evolution by banning polygyny, which had usually involved elite men and lowborn women. Elite women thus gained in reproductive importance. The Church thereby changed the culture not so much by making radically new rules but rather by reviving old rules and enforcing them more effectively.

Keep in mind that Christianity was much more rules-based than the old faith, particularly the watered-down paganism of the Imperial Era. Pagan Romans were more interested in developing a transactional relationship with their favorite god: “do this for me, and I’ll do that in exchange.” Their “religion” was not one as we understand the term:

It might be less confusing to say that the pagans, before their competition with Christianity, had no religion at all in the sense in which that word is normally used today. They had no tradition of discourse about ritual or religious matters (apart from philosophical debate or antiquarian treatise), no organized system of beliefs to which they were asked to commit themselves, no authority-structure peculiar to the religious area, above all no commitment to a particular group of people or set of ideas other than their family and political context. (North, 2013)

Thus, Christianity may have assisted cognitive evolution not only indirectly (by increasing the reproductive importance of elite women) but also directly – by favoring those individuals who could better learn and follow rules, and by punishing those who could not. Rule-following overlaps with cognitive ability, while also soliciting other mental domains and genetic factors (O’Gorman et al., 2008). At DRD4, for example, different alleles are associated with different degrees of susceptibility to social norms (Sasaki et al., 2013).

Were Christians aware that their faith could improve the general population not only in its morals but also in its capacity for morality? Did they believe that a Christianized population would progressively become more discerning and better able to follow rules? Origen seemed to think so. In his works, the righteous are seen as having the good qualities of “Abraham’s seed” and, as such, are naturally predisposed to correct behavior:

But, since it is by their morals and their works that Abraham’s children are identified, is it not also based on the logoi spermatikoi placed, I think, in certain souls that one must characterize those who are Abraham’s seed? (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 5)

But how could one rightfully reproach for not doing Abraham’s works he who completely lacks the quality of Abraham’s seed, from which comes the possibility of becoming Abraham’s child? … If a man who is not Abraham’s child was not the seed of any righteous person, he could not be reprimanded for being one of the sinners, since he would not have, by the seeds (of his forbears), any tendency to do good. (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 9-10)

I wonder whether it is possible for one who is not Abraham’s seed, but has the tendencies that Abraham owed to the seeds of his predecessors, to become such that, without originating from Abraham, he would be made similar to Abraham. (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 15)

Was the above reasoning common among mainstream Christians? Origen preceded it with a long, convoluted paragraph that implies a fear of “troubling” the reader:

Since these interpretations may trouble anyone who would conjecture about them without understanding them thoroughly, we will expose ourselves to the danger inherent in such questions wherever it is risky to speak and develop such ideas, even if they are consistent with reality. This is risky because the steward of God’s mysteries must also seek the right moment to present such doctrines without harming whoever listens and, even if the right moment is respected, take care to identify that which would be insufficient or superfluous and contrary to rational thinking, [and] examine also carefully whether those to whom he [the steward] makes such statements are his fellow servants or the servants of someone else, who is different from the Lord of lords. (Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, XX, 6-7)

Origen was an Egyptian of Greek heritage. He thus belonged to a fair-skinned minority who considered themselves better than the darker-skinned majority. This reality may have led him to think in ways that seemed divisive to the Church and the Roman authorities, notably his views on the “discolored” and “ignoble” indigenous Egyptians, as expressed by him in a widely circulated text:

But Pharao easily reduced the Egyptian people to bondage to himself, nor is it written that he did this by force. For the Egyptians are prone to a degenerate life and quickly sink to every slavery of the vices. Look at the origin of the race and you will discover that their father Cham, who had laughed at his father’s nakedness, deserved a judgment of this kind, that his son Chanaan should be a servant to his brothers, in which case the condition of bondage would prove the wickedness of his conduct. Not without merit, therefore, does the discolored posterity imitate the ignobility of the race. (Origen, Homily on Genesis, XVI, 1)

Such assertions, and the negative reactions to them, may explain why Origen was summoned to a Roman tribunal and given a bizarre choice: either renounce his faith or submit to “defilement” by an Ethiopian:

On account of his remarkable holiness and erudition he incurred the greatest jealousy and this stirred up even more those who were magistrates and prefects at that particular time. With devilish ingenuity the evildoers contrived to bring disgrace upon the man and, what is more, to mark out this sort of vengeance: that they would procure an Ethiopian for the purpose of causing defilement to his body. In response to this, Origen, not tolerating that deceptive plan of the devil, proclaimed the word that of the two propositions set before him he preferred to offer sacrifice. … In this way he fell from the glory of martyrdom in the judgement of the confessors and martyrs who were alive in his times, and he was cast out of the church. This happened at Alexandria. (Epiphanius of Salamis, Panaria 2: 64.2)

However, it is no easy matter to decide what should be chosen in preference to what. Very often it is necessary to choose that which is disagreeable over that which is disgraceful, as Susanna and Joseph did. But not always, for in order not to fall into the Ethiopian disgrace, Origen fell away entirely; thus the discernment of such matters is not easy. (Nemesius of Emesa, De Natura Hominis 29: 268-270)

Today, the word “Ethiopian” means someone from a country in the Horn of Africa. In Antiquity, it simply meant a Black African. As for the phrase “defilement to his body,” it apparently meant sexual intercourse, probably an act of sodomy in which Origen would play the passive role, since he had allegedly castrated himself to avoid the temptations of women. He thus chose apostasy as the lesser evil. We should keep in mind that early Christians often had negative attitudes toward Black people, as did many Jews and pagans of Antiquity (Frost, 1991; Goldenberg, 2003; Thompson, 1989).

Curiously, this incident goes unmentioned in almost all of the present-day works on Origen, even though it is attested by two writers of his time.

Conclusion

Origen was a voice in the wilderness, like most intellectuals of his age. There were no learned societies back then, nor were new ideas presented at conferences or published in journals. Origen inspired no one to pursue his views on the inheritance of mental and physical traits, probably because the smart fraction was too small to sustain a chain reaction of intellectual debate, as would happen later during the Enlightenment.

Moreover, Origen’s thinking still lacked the concept of selection by the environment – in this case, selection by the cultural environment. He thought that “bad seeds” are removed from the gene pool through divine action, and not through their failure to meet the cognitive demands of the culture. On this subject, as on others, his thinking followed the Christian view that things happen in fulfilment of God’s plan. This is not evolution by natural selection.

Christianity seems to have unintentionally rebooted cognitive evolution, mainly by banning non-procreative sex and by limiting hypogamy among elite men. The reproductive importance of elite women was thus restored. In addition, the new faith may have assisted cognitive evolution by favoring those individuals who were better at learning and following rules.

References

Akbari, A., Barton, A.R., Gazal, S., Li, Z., Kariminejad, M., Perry, A., Zeng, Y., Mittnik, A., Patterson, N., Mah, M., Zhou, X., Price, A.L., Lander, E.S., Pinhasi, R., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., & Reich, D. (2024). Pervasive findings of directional selection realize the promise of ancient DNA to elucidate human adaptation. bioRxiv 2024.09.14.613021; https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.14.613021

Angel, J.L. (1972). Biological relations of Egyptian and eastern Mediterranean populations during Pre-dynastic and Dynastic times, Journal of Human Evolution, 1(3), 307-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(72)90066-8

Augustine. (1968). The Fathers of the Church. Saint Augustine, vol. 60. The Retractations. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press.

Balloux F., Handley, L.J., Jombart, T., Liu, H., & Manica, A. (2009). Climate shaped the worldwide distribution of human mitochondrial DNA sequence variation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Biological Sciences, 276, 3447-3455. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0752

Brace, C.L., Seguchi, N., Quintyn, C.B., Fox, S.C., Nelson, A.R., Manolis, S.K., & Qifeng, P. (2006). The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A., 103, 242-247. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0509801102

Caldwell, J.C. (2004). Fertility control in the classical world: Was there an ancient fertility transition? Journal of Population Research, 21, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03032208

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms. A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press: Princeton. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691141282/a-farewell-to-alms

Clark, G. (2009). The domestication of man: the social implications of Darwin. ArtefaCToS, 2, 64-80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277275046_The_Domestication_of_Man_The_Social_Implications_of_Darwin

Clark, G. (2023). The inheritance of social status: England, 1600 to 2022. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(27), e2300926120 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300926120

Epiphanius (1860). Panaria. In: Corporis Haereseologici Vol. 2. Franciscus Oehler (ed.) (pp. 229-231). Berlin: Apud A. Asher and Sons. I am indebted to Sr. Mechtilde O’Mara for the English translation.

Frost, P. (1991). Attitudes towards Blacks in the early Christian era. The Second Century, 8(1), 1-11. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319184071_Attitudes_toward_Blacks_in_the_Early_Christian_Era

Frost, P. (2015). The Past is Another Country. The Unz Review, August 15. https://www.unz.com/pfrost/the-past-is-another-country/

Frost, P. (2019). The Original Industrial Revolution. Did Cold Winters Select for Cognitive Ability? Psych, 1(1), 166-181. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych1010012

Frost, P. (2022). When did Europe pull ahead? And why? Peter Frost’s Newsletter, November 21. https://www.anthro1.net/p/when-did-europe-pull-ahead-and-why

Goldenberg, D.M. (2003). The Curse of Ham. Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691123707/the-curse-of-ham

Harris, W. (1999). Demography, Geography and the Sources of Roman Slaves. Journal of Roman Studies, 89, 62-75. https://doi.org/10.2307/300734

Hoffecker, J.F. (2002). Desolate landscapes. Ice-age settlement in Eastern Europe. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Hopkins, K. (1965). Contraception in the Roman Empire. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 8(1), 124-151. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500003935

Kuijpers, Y., Domínguez-Andrés, J., Bakker, O.B., Gupta, M.K., Grasshoff, M., Xu, C.J., Joosten, L.A.B., Bertranpetit, J., Netea, M.G., & Li, Y. (2022). Evolutionary Trajectories of Complex Traits in European Populations of Modern Humans. Frontiers in Genetics, 13, 833190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.833190

Melchior, L., Lynnerup, N., Siegismund, H.R., Kivisild, T., & Dissing, J. (2010). Genetic diversity among ancient Nordic populations, PLoS ONE, 5(7), e11898. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011898

Nemesius of Emesa. (1975). De Natura Hominis. G. Verbeke, J.P. Moncho (eds). (pp. 121-122). Leiden: Centre de Wulf-Mansion. I am indebted to Sr. Mechtilde. O’Mara for the English translation.

North, J. (2013). The development of religious pluralism. In: The Jews among pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire (pp. 174-193). Routledge.

O'Gorman, R., Wilson, D. S., & Miller, R. R. (2008). An evolved cognitive bias for social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(2), 71-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.07.002

Origen. (1982). Origène. Commentaire sur Saint-Jean. Tome IV (Livres XIX et XX). Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf.

Origen. (1982). The Fathers of the Church, vol. 71. Origen. Homilies on Genesis and Exodus. Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press.

Pang-White, A.A. (2001). The fall of humanity: Weakness of the will and moral responsibility in the later Augustine. Medieval Philosophy and Theology, 9, 51-67. https://doi.org/10.5840/medievalpt2000914

Perry, M.J. (2013). Gender, Manumission, and the Roman Freedwoman. Cambridge University Press.

Piffer D, Dutton, E., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2023). Intelligence Trends in Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of Roman Polygenic Scores. OpenPsych. Published online July 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.26775/OP.2023.07.21

Piffer, D., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2024). Evolutionary Trends of Polygenic Scores in European Populations from the Paleolithic to Modern Times. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 27(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2024.8

Roetzel, C.J. (2000). Sex and the single god: celibacy as social deviancy in the Roman period. In: S.G. Wilson and M. Desjardins (eds). Text and Artefact in the Religions of Mediterranean Antiquity. Essays in Honour of Peter Richardson (pp. 231-248), Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Sasaki, J. Y., Kim, H. S., Mojaverian, T., Kelley, L. D. S., Park, I. Y., & Janušonis, S. (2013). Religion Priming Differentially Increases Prosocial Behavior among Variants of the Dopamine D4 Receptor (DRD4) Gene. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8, 209-215. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsr089

Sullivan, V. (2009). Increasing Fertility in the Roman Late Republic and Early Empire. MA thesis, History, North Carolina State University. https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/handle/1840.16/812

Thompson, L.A. (1989). Romans and Blacks, London: University of Oklahoma Press/Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Romans-and-Blacks-Routledge-Revivals/Thompson/p/book/9780415749954

Source: Peter Frost's Newsletter

Comments

Post a Comment